2024

- Orientation to the topic

- On fertility

- The country and the city

- An outline of the Pentateuch

- Character

- Building

- Building 2

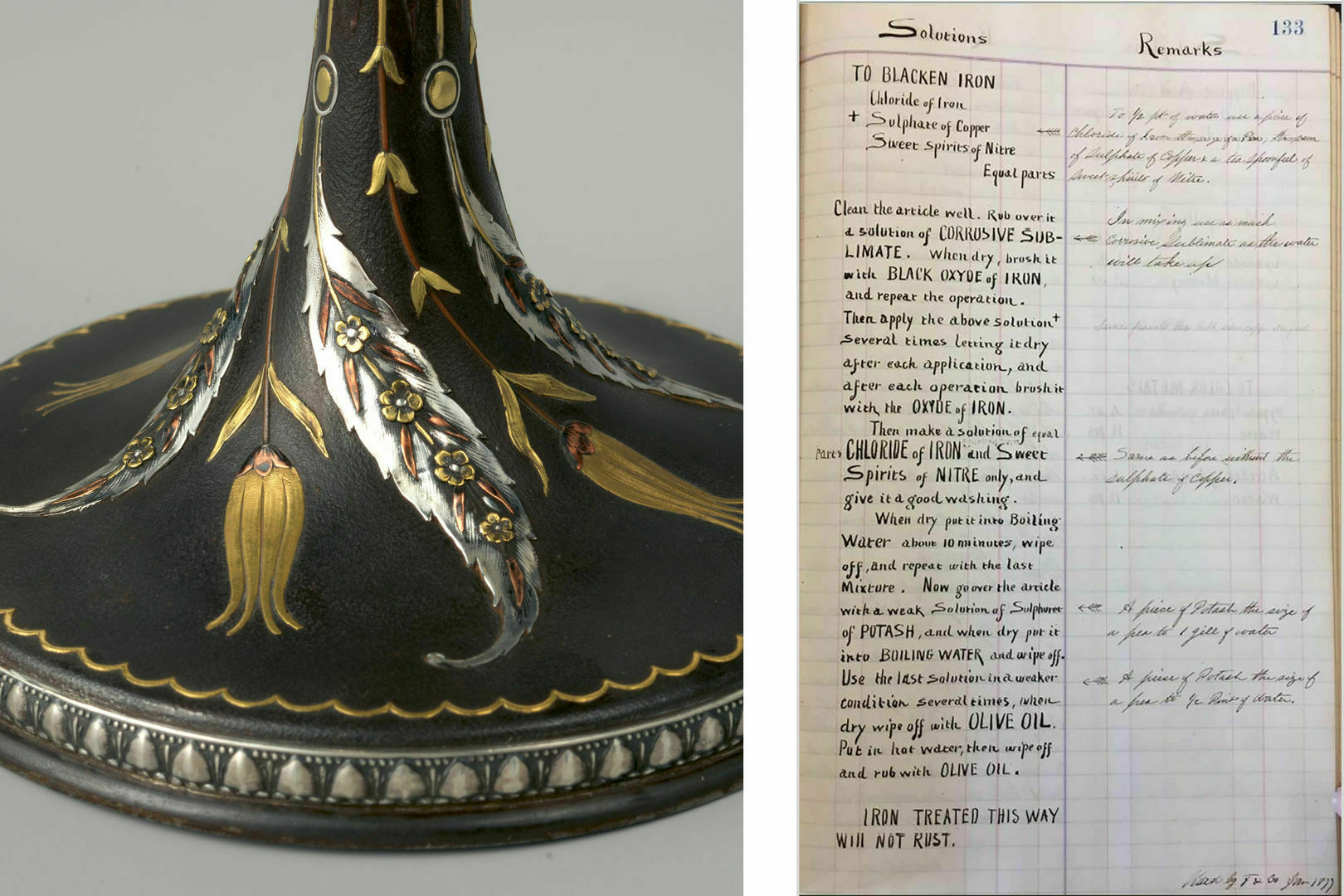

- Building 3: practices of making

- Building 4: creative fidelity

- Building 5: cunning works

- Building 6: diaspora

- The City and the City

- Archetype and Antithesis

- Hypothesis

- Secondary Epic

- Political Theology

- City and Church

- A Digression on Longtermism

- Causes

- A Digression on Reading

- Parallels

- Ends and Means

- The City of God Coming Down

- Last Things

- Prologue to the whole: The Creation (Genesis 1)

- The history of humanity (Genesis 2–11)

- Making and naming

- Commanding and disobeying

- Zooming in: Abraham and his descendants (Genesis 12–36)

- Hospitable and inhospitable

- Abraham and the three visitors

- Lot in Sodom

- Abimelech

- Dinah and the family of Hamor

- Barrenness and fertility

- Sarai/Sarah

- Rebekah

- Rachel

- Elder and younger

- Ishmael and Isaac

- Esau and Jacob

- The children of Leah and the sons of Rachel

- The children of Israel in Egypt (Genesis 37-Exodus 12)

- Beneficiaries: Genesis 37–50

- Slaves: Exodus 1–12

- The children of Israel in the wilderness (Exodus 13-Deuteronomy 34)

- Wandering begun (Exodus 13–18)

- Ascent to Sinai (Exodus 19-Leviticus 27)

- Response to Sinai (Numbers 1–8)

- Ordering

- Cleansing

- Dedicating

- Remembering

- Wandering resumed (Numbers 9-Deuteronomy 33)

- Ascent to Nebo/Pisgah (Deuteronomy 34)

starting over

Around a month ago, I mentioned that I had just read and really enjoyed Robin Sloan’s novel Moonbound. And that’s true! But what I didn’t say at the time is that I definitely didn’t get the most out of my reading experience, didn’t have full concentration as I read. And I know why. It was because of one page near the beginning of the galley I read, a page with three words on it:

As I read, I kept looking back at that page, as though hoping that the words would dissolve and be replaced by the promised cartography. Because when I am reading a work of fiction there are few things I love more than a map.

I think I would have missed the map even if I hadn’t been told that there would be one, but to know that a map was being made but I did not have it was agonizing. Thus my inconsistent attentiveness.

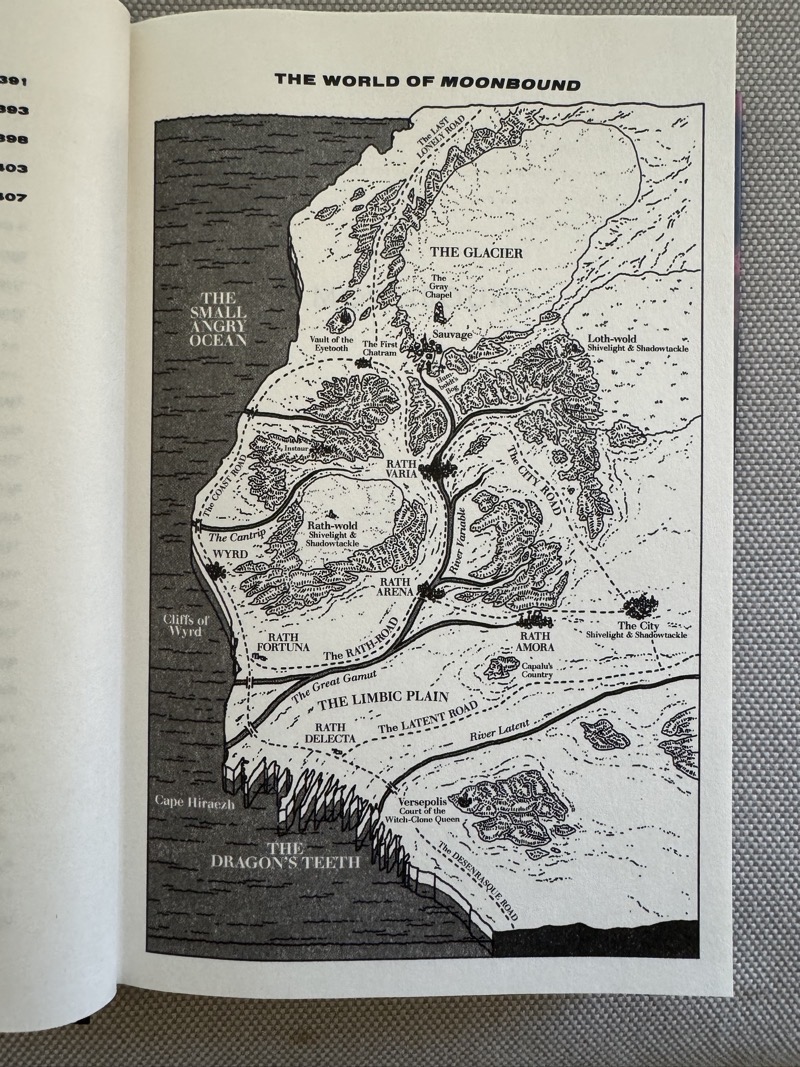

But today, this very afternoon, my very own hardcover copy of the book arrived, and when I opened it up I saw this:

Ah. Ah yes. I will now be re-reading Moonbound, and this time I’ll get the full and proper experience.

Shooting on film — with a Nikon F100 — for the first time in many years. The natural bokeh is great, and the texture, but wow am I out of practice. I need to re-learn setting exposure and even proper focusing. (Also: there are so many varieties of film to choose from now!)

Here’s a long post, with many links, explaining how I’ve sorta-kinda-in-a-way written a book in blog posts.

the wanderers and the city

My earlier posts in this series (which began by reading Genesis but has since expanded) are:

The Pentateuch concludes with the death of Moses and the arrival of the children of Israel at the doorstep of the Promised Land. As in the next books (Joshua and Judges) they consolidate their position, we’re moving, as I noted in an earlier post, from a world of nomadic pastoralists to a world of city dwellers — or, anyway, a world in which the embodiment of the Israelite identity is a city, Jerusalem, conceived first as the residence of the King and only later as the center of the cult of Yahweh.

This change raises certain questions about the theology and ethics of building, especially building a city, and as it happens I wrote a series of posts about that some years ago on my old Text Patterns blog:

The invocation of the Diaspora leads to a reflection on the city that in Scripture opposes Jerusalem: Babylon. Here are the entries in my Encyclopedia Babylonica:

I stopped writing then because I was confused about a number of things. But I am now seeing certain connections. The series on building (which focused on the Davidic era) and the series on Babylon (which focused on the era that ended the Davidic line) are, properly speaking, elements in a larger theology of the city, which I explored by writing about Augustine’s City of God:

(There’s some overlap to these series because they were written independently of one another and sometimes in forgetfulness.) And I have many other posts and essays that seem to be on unrelated subjects but may not be. For instance, Ruskin — my admiration for whom I recently reaffirmed — begins The Stones of Venice by claiming that three cities associated with the mastery of the sea stand above all others: Tyre, Venice, and London. His theology of art and architecture is also a theology of the city, meant for Londoners, as the successors to the Venetians, to heed. There’s even a strange passage early in Stones in which Ruskin claims that all three of Noah’s sons founded cultures that contributed to the rise of architecture, thereby reconnecting the theme of the City to the book of Genesis.

Related: there is a long and powerful tradition of writing about London as the city, the paradigmatic or exemplary city, the city as a “condensed symbol,” to return to a theme from my last post: this is what Blake does repeatedly, and Dickens, and H. G. Wells, especially in Tono-Bungay. There are some powerful connections between Tono-Bungay and Little Dorrit that I want to explore in a future post.

It’s strange that I have written a book’s worth of reflections on all this stuff. But what does this non-book say? Heck, what do I even mean by “all this stuff”?

I think these concerns arose in my mind because (a) I was, and still am, frustrated by the ongoing dominance of H. Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture, a book that still establishes the categories for thinking about how Christians live in “the world”; and (b) I felt that a richer, deeper picture is offered, however obliquely, in the poetry and prose of W. H. Auden in the decade following the end of the Second World War. (It’s noteworthy, I think, that Auden’s work is contemporaneous with Niebuhr’s: that WW2 prompted full-scale reconsiderations of the ideal character of culture and society is what my book The Year of Our Lord 1943 is all about.) Auden, instead of writing about “culture,” writes about “the city,” and that reformulation strikes me as especially resonant and full of promise, especially given the prominence of the Jerusalem/Babylon opposition in the Bible.

Now, Auden writes about these matters in The Shield of Achilles, which I have edited — but he writes about them more extensively in his previous book Nones, which I may also edit. Even if I don’t get the chance to make a critical edition of that collection, I’m going to be re-reading it, and maybe after I do I’ll have a better idea of how to put all these thoughts, which have obviously been occupying my mind for quite some time, into better order.

But whether I should try to turn all this into an actual book? I have my doubts about that. For one thing, few if any publishers would be interested in publishing something that is largely available online for free. For another — and this actually may be more important — do all these thoughts really belong in a book, between covers, with a beginning an ending? Some projects ought not to be closed and completed; some projects ought to be ramifying and exploratory. I suspect this is one such project. I may have more to say about that in future posts.

Also, here’s Robin explaining in a video the language/script/typeface he developed for his fabulous new novel Moonbound. I love the fact that Robin’s one previous video was posted fourteen years ago. I can’t wait to see what he posts in 2038.

Surprising moment from this interview with Robin Sloan:

[Gibson-Faulkner] Theory is, of course, the great policy planning framework of the Anth, which is what I call human civilization at its apex—our near future. The idea is that it’s a system for imagining and executing big projects that actually works. The theory emerges from the intersection of two maxims. First, there’s William Gibson: “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.” Then, there’s William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Mashing those together, we get an interesting view of the present, not as a point on a continuum, but rather a smear, a bleed, a diffusion of events and possibilities. (It’s well-known that early Gibson-Faulkner theorists were also influenced by Alan Jacobs and his concept of “temporal bandwidth”.)

To which I 🤯 and ☺️. (It’s really Thomas Pynchon’s concept more than mine, but I’ll take credit.)

George Lois’s library — in his apartment in the West Village — is my kind of workspace. And the apartment, at $5,600,000, is a bargain!

An outstanding post by Mike Sacasas about technology and work — the kinds of work we value and the kinds of work we ought to value.

I wrote about character in the Pentateuch.

character

The book of Genesis features a large number of distinct and memorable characters: Adam and Eve, Noah, Abraham and Sarah, Esau and Jacob, Joseph. Our attention is captured for the longest periods by Abraham and Jacob, but often we see them in relation to their children and other family members. They rarely occupy the stage alone. But the rest of the Pentateuch really only has one character: Moses. A few others hover around the margins, but they are mere sketches of persons. Only Moses is fully a character.

After the Pentateuch, with Joshua, Judges, and Ruth, the narrative resumes its proliferation of personages — only to narrow its focus again with David. We stay with David for a very long time before the story pulls back out to describe the wide range of kings and prophets who follow him.

So in the Hebrew Bible we see this regular alternation of (a) sweeping narrative that emphasizes ongoing familial or cultural patterns and (b) intensely focused stories that trace the development of individual lives. Sweep is the default, but you never know when the story will zoom in for an extended close-up.

One way to think about this: Certain patterns of behavior — most of them involving waxing and waning devotion to YHWH and obedience to His commandments — characterize the children of Israel; but some people seem to embody these patterns in powerful, profoundly exemplary ways. You could say that someone like David is, to adapt a concept from the anthropologist Mary Douglas, a human condensed symbol. (Cf. p. 10: “For Christian examples of condensed symbols, consider the sacraments, particularly the Eucharist and the Chrisms. They condense an immensely wide range of reference summarized in a series of statements loosely articulated to one another.”) The complicated and inconstant history of Israel is condensed and made visible and comprehensible in a handful of key figures. This is how Abraham functions in Paul’s letters: a condensed symbol of faith in action.

And I wonder if a character can only serve as this kind of symbol if he or she is complex, with hidden depths. Here I am thinking of Erich Auerbach’s famous contrast between the Homeric poems and the Hebrew Bible. The “basic impulse of the Homeric style” is

to represent phenomena in a fully extemalized form, visible and palpable in all their parts, and completely fixed in their spatial and temporal relations. Nor do psychological processes receive any other treatment: here too nothing must remain hidden and unexpressed. With the utmost fullness, with an orderliness which even passion does not disturb, Homer's personages vent their inmost hearts in speech; what they do not say to others, they speak in their own minds, so that the reader is informed of it.

By contrast, the narration of Genesis features

the externalization of only so much of the phenomena as is necessary for the purpose of the narrative, all else left in obscurity; the decisive points of the narrative alone are emphasized, what lies between is nonexistent; time and place are undefined and call for interpretation; thoughts and feeling remain unexpressed, are only suggested by the silence and the fragmentary speeches; the whole, permeated with the most unrelieved suspense and directed toward a single goal (and to that extent far more of a unity), remains mysterious and “fraught with background.”

Perhaps only the character “fraught with background” can become a condensed symbol.

Portishead’s Dummy is equidistant in time from (a) now and (b) A Hard Day’s Night.

My pledge: I will never ever read an article about “How AI will change X” — no matter what X is.

What a great post by Sara Hendren AKA @ablerism : “When my teenagers play patiently and attentively with someone’s much younger children at a party, people will compliment me warmly: They were so kind! I thank them but also tell them plainly that my kids were instructed to do so — they are no more naturally and authentically generous hosts as adolescents than anyone else. We just don’t make it optional at our house. And they’re old enough now to see the fruits of constraining their natural impulses. When you behave in prosocial ways, the prosocial feeling will often follow, not lead.”

A friend sent me this extraordinary music video by RAYE — please do watch the whole thing. It’s a parable, a warning, a word of exhortation. It moves from the emptiness of lonely self-loathing, to the emptiness of celebrity and success, to … well, just watch to see where it ends up.

I wrote a June update for my Buy Me a Coffee supporters. I’m very grateful for those supporters because they enable me to keep blogging, which I love to do.

I made a little outline of the Pentateuch — and explained why it matters that such an outline is so easily made.

the Pentateuch in brief outline

This kind of thing can seem reductive, and if you rely on it overmuch it certainly will be, but note how it calls attention to the relentless patterning of the narrative. As Robert Alter has pointed out, the long-time obsession with sources among scholars of the Hebrew Bible — their slightly mad-eyed teasing out of the contributions of their posited authors J, E, D, and P — led them to the assumption that “the redactors were in the grip of a kind of manic tribal compulsion, driven again and again to include units of traditional material … for reasons they themselves could not have explained.” Yet if that were true, why does an outline of the Pentateuch look so orderly — indeed, almost excessively so?

Gabriel Josipovici has argued in his wonderful and lamentably neglected The Book of God that “the inventors of the documentary hypothesis” — the leading biblical scholars of a century to a century-and-a-half ago —

believed that by trying to distinguish the various strands they were getting closer to the truth, which, in good nineteenth-century fashion, they assumed to be connected with origins. But in practice the contrary seems to have taken place. For their methodology was necessarily self-fulfilling: deciding in advance what the Jahwist or the Deuteronomist should have written, they then called whatever did not fit this view an interpolation. But this leads, as all good readers know, to the death of reading; for a book will never draw me out of myself if I only accept as belonging to it what I have already decreed should be there.

What my little outline shows is what anyone can see if they read the text — that however many authors and redactors worked on the Pentateuch, it’s anything but a chaotic assemblage of contradictory traditions; rather, it is almost obsessively built upon readily identifiable patterns, patterns that work like musical themes or Wagnerian leitmotifs.

I’ll conclude with a more general point. You should not be able to get a doctorate in the humanities without having this declaration tattooed on the back of your hand: “A book will never draw me out of myself if I only accept as belonging to it what I have already decreed should be there.”