diseases of the intellect

Twenty years ago, I had an exceptionally intelligent student who was a passionate defender of and advocate for Saddam Hussein. She wanted me to denounce the American invasion of Iraq, which I was willing to do — though not in precisely the terms that she demanded, because she wanted me to do so on the ground that Saddam Hussein was a generous and beneficent ruler of his people. That is, her denunciation of America as the Bad Guy was inextricably connected with her belief that there simply had to be on the other side a Good Guy. The notion that the American invasion was wrong but also that Saddam Hussein’s tyrannical rule was indefensible — that pair of concepts she could not simultaneously entertain. Because there can’t be any stories with no Good Guys … can there?

This student was not a bad person — she was, indeed, a highly compassionate person, and deeply committed to justice. She was not morally corrupt. But she was, I think, suffering from a disease of the intellect.

What do I mean by that? Everyone’s habitus includes, as part of its basic equipment, a general conceptual frame, a mental model of the world that serves to organize our experience. Within this model we all have what Kenneth Burke called terministic screens, but also conceptual screens which allow us to employ key terms in some contexts while making them unavailable in others. We will not be forbidden to use a word like “compassion” in responding to our Friends, but it will not occur to us to use it when responding to our Enemies. (Paging Carl Schmitt.)

My student’s conceptual screens made certain moral descriptions — for instance, saying that a particular politician or action is “cruel” or “tyrannical” — necessary when describing President Bush but unavailable when describing Saddam Hussein. But I seriously doubt that this distinction ever presented itself to her conscious mind. It worked in the background to determine which thoughts were allowed to rise to conscious awareness and therefore become a matter for debate. To return to a distinction that, drawing on Leszek Kołakowski, I have made before, the elements of our conceptual screens that can rise to consciousness belong to the “technological core” of human experience, while those that remain invisible (repressed, a Freudian would say) belong to the “mythical core.”

I could see these patterns of screening in my student; I cannot see them in myself, even though I know that everything I have said applies to me just as completely as it applies to her, if not more so.

Certain writers are highly concerned with these mental states, and the genre in which they tend to describe them is called the Menippean satire. (That link is to a post of mine on C. S. Lewis as a notable writer in this genre, though this has rarely been recognized.) In his Anatomy of Criticism, Northrop Frye wrote,

The Menippean satire deals less with people as such than with mental attitudes. Pedants, bigots, cranks, parvenus, virtuosi, enthusiasts, rapacious and incompetent professional men of all kinds, are handled in terms of their occupational approach to life as distinct from their social behavior. The Menippean satire thus resembles the confession in its ability to handle abstract ideas and theories, and differs from the novel in its characterization, which is stylized rather than naturalistic, and presents people as mouthpieces of the ideas they represent.... The novelist sees evil and folly as social diseases, but the Menippean satirist sees them as diseases of the intellect. [p. 309]Thus the title of my post.

I think much of our current political discourse is generated and sustained by such screening, screening that an age of social media makes at once more necessary and more pathological. Also more universally “occupational,” because in some arena of our society — journalism and the academy especially — the deployment of the correct conceptual screens becomes one’s occupational duty, and any failure so to maintain can result in an ostracism that is both social and professional. And that’s how people, and not just fictional characters, become “mouthpieces of the ideas they represent.”

None of this is hard to see in some general and abstract sense, but it’s hard to see clearly. What Lewis calls the “Inner Ring” is largely concerned to enforce the correct conceptual screens, and because those screens don’t rise to conscious awareness, much less open statement, the work of enforcement tends to be indirect and subtle, and perhaps for that very reason irresistible. It’s like being subject to gravity.

In certain cases the stress of maintaining such conceptual screens grows to be too much for a person; the strain of cognitive dissonance becomes disabling. Crises in one’s conceptual screening, as Mikhail Bakhtin wrote in Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, were of particular interest to Dostoevsky:

In the menippea there appears for the first time what might be called moral-psychological experimentation: a representation of the unusual, abnormal moral and psychic states of man — insanity of all sorts (the theme of the maniac), split personality, unrestrained daydreaming, unusual dreams, passions bordering on madness, suicides, and so forth. These phenomena do not function narrowly in the menippea as mere themes, but have a formal generic significance. Dreams, daydreams, insanity destroy the epic and tragic wholeness of a person and his fate: the possibilities of another person and another life are revealed in him, he loses his finalized quality and ceases to mean only one thing; he ceases to coincide with himself. [pp. 116-19]This deserves at least a post of its own. But in general it’s surprising how powerful people’s conceptual screens are, how impervious to attack. But maybe it shouldn’t be surprising, since those screens are the primary tools that enable us to “mean only one thing” to ourselves; they allow us to coincide with ourselves in ways that soothe and satisfy. The functions of the conceptual screens are at once social and personal.

All this helps to explain why the whole of our public discourse on Israel and Palestine is so fraught: the people participating in it are drawing upon some of their most fundamental conceptual screens, whether those screens involve words like “colonialism” or words like “pogrom.” But this of course also makes rational conversation and debate nearly impossible. The one thing that might help our fraying social fabric is an understanding that, when people are wrong about such matters — and that includes you and me —, the wrongness is typically not an indication of moral corruption but rather the product of a disease of the intellect.

And we all live in a social order whose leading institutions deliberately infect us with those diseases and work hard to create variants that are as infectious as possible. So my curse is straightforwardly upon them.

I don’t want to pretend that I am above the fray here. I have Opinions about the war, pretty strong ones at that, and I have sat on this post for a week or so, hemming and hawing about whether I have an obligation to state my position, given the sheer human gravity of the situation. But while I’m not wholly ignorant, I don’t think that my Opinions are especially well-informed, and if I put them before my readers — well, I feel that that would be presumptuous. (Even though I live in an era in which most people find it disturbing or even perverse if you hold views without proclaiming them.) There are thousands of writers you could read to find stronger and better-informed arguments than any I could make.

But I do think I can recognize and diagnose diseases of the intellect when I see them. That’s maybe the only contribution I can make to this horrifying mess of a situation, and I’m counting on its being more useful if it isn’t accompanied by a statement of position.

I hope this won’t be taken as a plague-on-both-your-houses argument, though I’m sure it will. (I have made such arguments about some things in the past, but I am not making one here.) When you write, as I do above, about the problem with a conceptual screen that requires one purely innocent party and one purely guilty party, you will surely be accused of “false equivalency” or “blaming the victim.” But you don’t have to say that a person, or a nation, or a people is utterly spotless in order to see them as truly victimized. Sometimes a person or a nation or a people is, to borrow King Lear’s phrase, “more sinned against than sinning” without being sinless. And I think that applies no matter what role you assign to which party in the current disaster.

With all that said, here are some concluding thoughts:

- A monolithic focus on assigning blame to one party while completely exonerating the other party is a sign of a conceptual screen working at high intensity.

- Such a monolithic focus on blame-assignation is also incapable of ameliorating suffering or preventing it in the future. (Note the use of the italicized adjective in these two points: the proper assessment of blame is not a useless thing, but it’s never the only thing, and it is rarely the most important thing, for observers to do.)

- If you are consumed with rage at anyone who does not assign blame as you do, that indicates two things: (a) you have a mistaken belief that disagreement with you is a sign of moral corruption, and (b) your conceptual screen is under great stress and is consequently overheating.

- It is more important, even if it’s infinitely harder, for you to discover and comprehend your own conceptual screens that for you to see the screens at work in another’s mind. And it is important not just because it’s good for you to have self-knowledge, but also because our competing conceptual screens are regularly interfering with our ability to develop practices and policies that ameliorate current suffering and prevent future suffering.

- A possible strategy: When you’re talking with someone who says “Party X is wholly at fault here,” simply waive the point. Say: “Fine. I won’t argue. So what do we do now?” Then you might begin to get somewhere — though you're more likely to discover that your interlocutor's ideas begin and end with the assigning of blame.

Hi, we’d like to join your LinkedIn network

My old internet friend Erin Kissane on Meta in Myanmar: “My aim with this series is to give mostly-western makers and users of social technology a sense of one US-based technology company’s role in what happened to just one group of people in just one place over a very limited time range.” An extraordinary series of posts, an analysis worthy of being published in a major newspaper or journal … but it’s just out there on the open web for everyone to see.

I do not think human beings are the last stage in the evolutionary process. Whatever comes next will be neither simply organic nor simply machinic but will be the result of the increasingly symbiotic relationship between human beings and technology.

Bound together as parasite/host, neither people nor technologies can exist apart from the other because they are constitutive prostheses of each other.

But which one’s the parasite and which the host? Add odd point to be omitted, considering its importance.

My friend Tim Larsen: “Yes, I’m one of those people who had a Netflix DVD subscription right to the very end: 29 September 2023.”

I wrote about the imperative to repair things that are only mostly dead.

only mostly dead

The other day I wrote about the absolute cataract of essays and articles these days proclaiming the death of something — something, anything, everything: capitalism, liberalism, Trumpism, tradition, conservatism, the novel, poetry, movies … the list goes on and on.

Today I’m wondering how much this habit of mind arises from an economic system built around planned obsolescence and unrepairable devices. If we are deeply habituated to throwing away a bought object when it is no longer performing excellently, then why not do the same with ideas? Hey, this thing I believe in no longer commands universal assent. Let’s flush it.

And for that matter why not take the same approach to people? If you’re in Canada and having suicidal thoughts, then you just might have a counselor suggest medically-assisted suicide. You’re hardly worth repairing, are you? Let’s just ease you into death and get you off our books.

It shouldn’t take a Miracle Max to tell the difference between dead and mostly dead, which is also slightly alive. But our social order can’t even tell the difference between dead and imperfect — because the Overlords of Technopoly profit when that distinction is unavailable to us. And we should always remember that when someone declares that one object or idea is dead, they’re probably quite ready to sell us a new one.

Where there’s life, there’s hope; and where there’s hope, there’s the imperative to repair. Technopoly is a system of despair.

UPDATE: My friend Austin Kleon sends me this, a 2012 entry from the late Tom Spurgeon’s Comics Reporter: “So people are going to the movies less frequently. Really, things have been dying and changing since forever. People don’t buy Big Little Books anymore; people don’t walk on the promenade anymore; people don’t go to roller derby. Actually, they do all of those things; they just don’t do them in great numbers. One of the wonderful things about treating art as an art rather than as a public commodity is that you focus on the quality of the experience and benefiting the artists directly; you don’t worry about the size of something for the sake of worrying about the size of something.” So, so much agree.

Paul Johnson, Dies Natalis

Shadows on the driveway

This eclipse is pretty weird.

Just texted a friend: “So much of my life with technology revolves around (a) realizing that what I had thought was a feature is a bug and (b) realizing that what I had thought was a bug is a feature.”

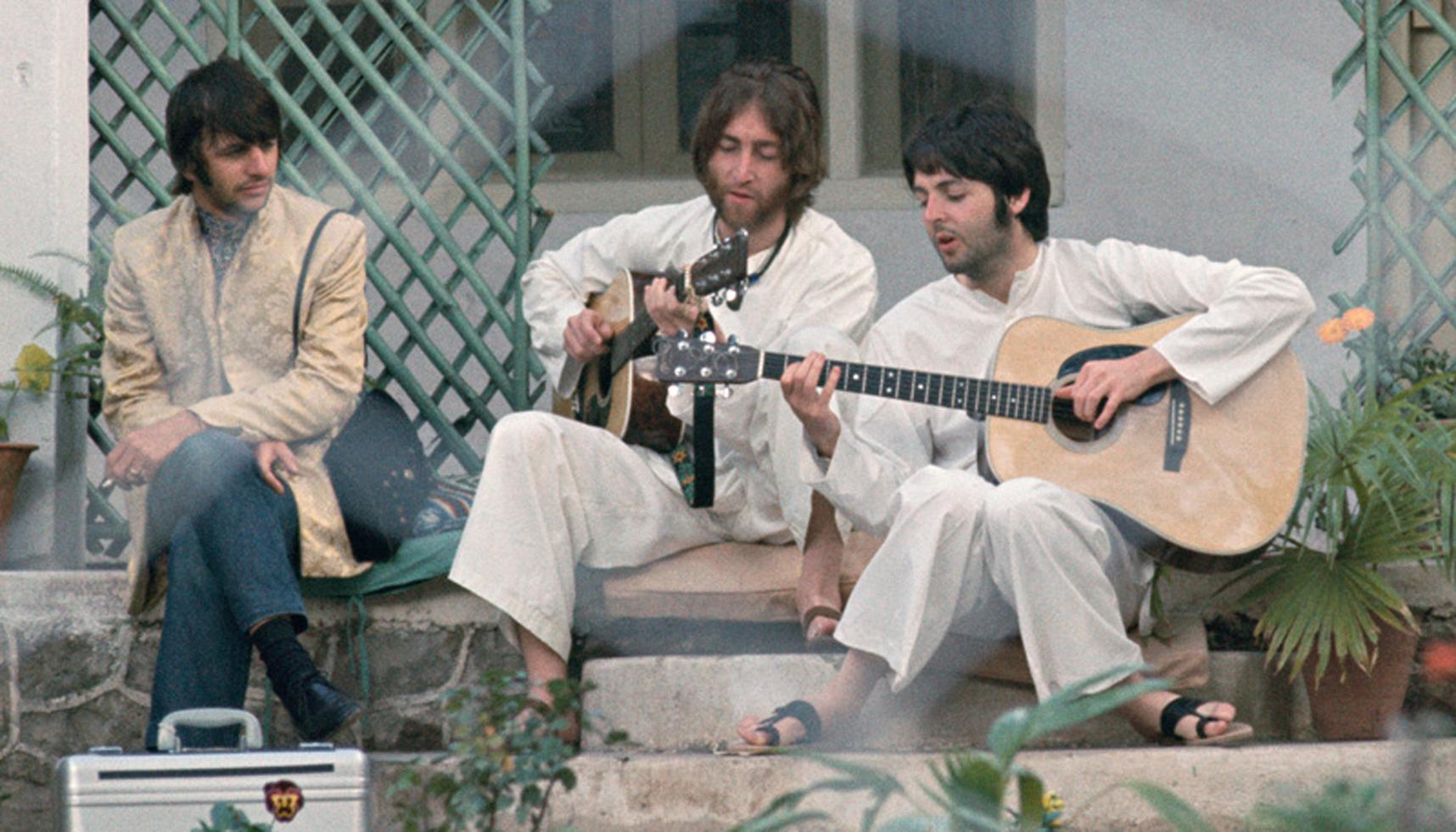

I wrote a kind of follow-up to my “Resistance in the Arts” essay, focusing mainly on the Beatles.

begin here

The essay that I published earlier this year on “Resistance In the Arts” was largely inspired by my reading of one book, Ian MacDonald’s simultaneously maddening and magisterial Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. It’s important to to pay attention to that subtitle. McDonald wants to argue that the music that the Beatles made exemplifies the cultural movement that we call “the Sixties” better than anything else does, and he makes a very good case for that idea, in which I’m quite interested. But I’m even more interested in the final words of the actual narrative of the book, words written by way of introduction to a chronology of the 1960s. (That chronology, which serves as an appendix to the book, consists of four columns: what the Beatles were doing; what else was happening in pop music in the UK; key political and social events; and developments in the arts more generally — for instance, cinema, jazz, classical music, poetry, etc.) Here’s what MacDonald says to conclude his narrative and introduce that chronology:

There is a great deal more to be said about the catastrophic decline of pop (and rock criticism) — but not here. All that matters is that, when examining the following Chronology of Sixties pop, readers are aware that they are looking at something on a higher scale of achievement than today’s — music which no contemporary artist can claim to match in feeling, variety, formal invention, and sheer out-of-the-blue inspiration. That the same can be said of other musical forms — most obviously classical and jazz — confirms that something in the soul of Western culture began to die during the late Sixties. Arguably pop music, as measured by the singles charts, peaked in 1966, thereafter beginning a shallow decline in overall quality which was already steepening by 1970. While some may date this tail-off to a little later, only the soulless or tone-deaf will refuse to admit any decline at all. Those with ears to hear, let them hear.So that’s MacDonald’s blunt assessment. And what launched my essay was a double response to that paragraph. On the one hand, I thought that in relation to pop music, he is 100% correct. But the sweeping judgment I have highlighted, about “the soul of Western culture,” is less readily defensible. He wrote those words in the mid or late 1990s. In retrospect, it seems to me that classical music was in a much, much better place in the 1990s than it had been in the 1960s; similarly, the architecture of the Nineties was significantly more varied and inventive than architecture in the Sixties, partly as a result of certain technical changes, including CAD (computer-assisted design). I could give other examples.

Thus MacDonald’s Grand Narrative about Western culture — his assumption that Western culture is one giant, uniform Thing that is always on a single trajectory, either ascending or descending — is just nonsense, if also an all-too-common form of nonsense.

But: at any given moment in history in any given location, certain specific arts may operate at a higher level than they do at other times, or in other places. So I began my essay by noting how much better English drama was in the period between 1590 and 1620 than it ever had been before or ever would be again — and that is true even if you factor Shakespeare out of the equation. (You still have Marlowe, Webster, Jonson, Beaumont & Fletcher, etc.) Ditto the outpouring of genius in pop music between, say, 1962 and 1975, an outpouring that’s astonishing even if you factor the Beatles out of the equation. And what such stories suggest, or anyway what they suggest to me, is that circumstances can conspire to make a particular art form more dynamic at some moments than it is at others.

I’m not sure that I made myself perfectly clear in that essay. I’m a bit frustrated with it. But I still think that the chief point that I was pursuing is an absolutely vital one. We need to think about what kinds of circumstances encourage outstanding art and what kinds militate against outstanding art. In the essay I argued that there must be a balance between forces that enable and forces that resist, and that that balance is at once technological, economic, and social. You have to be able to do and make certain things, but the making should not be too easy, just as you should not be totally blocked from achieving what you’re trying to achieve. I mentioned the Beatles song “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which creates special effects through the use of five tape loops, loops which are placed within the song in a cunningly designed sequence. The loops (made by Paul McCartney on a tape recorder he had at home) were not easy to create, which is why there were only five of them; but five turned out to be the perfect number, because that allowed both repetition and variation, both of which are key to successful art. Moreover, while the Beatles were free to add those tape loops to the song, they were not (yet) free to spend six months in the studio or to make 10-minute songs.

The Beatles were immensely talented, to be sure, and were surrounded by equally talented support in the producer George Martin and the engineer Geoff Emerick; but Taylor Swift is also extremely talented and knows how to surround herself with gifted producers, engineers, and musicians, and yet, for all her enormous popularity, she isn’t changing the face of music. Her musical language is basic and predictable: given any two consecutive chords of a Swift song, the listener can predict with a high degree of confidence what the next one will be. She has not, to my knowledge, written or performed a single song that alters even in the tiniest way the landscape of pop music, while, by contrast, there was a period of five years during which the Beatles were doing that every few weeks. Maybe those conditions simply can’t be recreated; maybe Taylor Swift, and indeed everyone working in the aftermath of the Beatles’ meteoric career, is, in Harold Bloom’s term, belated. But, on the other hand, maybe we’re too quick to accept belatedness.

One of the reasons we still listen to the Beatles (one of the reasons we still read or watch Shakespeare) is that for them, in their time and place, they discovered the ideal balance between enablement and resistance; the stars aligned for them. (When the Beatles broke up the stars went out of alignment, forever; even if John Lennon had lived and the band had reassembled, they wouldn’t have been able to come close to what they achieved in the Sixties. The balance of resistances had altered, and for the worse.) I tried — and, I think, failed — to figure out what specifically it looks like when the stars so align for artists, and then to go beyond that to ask a question: Is there anything that we can do to help those stars to align?

You know, when absolutely staggering greatness shows up, I don’t think we can pay too much attention to it. We should not just look at it and applaud it, but also try to ask ourselves, in the most serious and intense way possible, What enabled that, and how can we enable something else that’s equally great?

I don’t know the answers to those questions, but I keep thinking about a tossed-off comment in Ian MacDonald’s book. He’s writing about a song that John and Paul wrote together — I don’t remember which one, but it doesn’t matter — and in that song there’s a moment when the standard, the expected, harmonic progression calls for an A major chord — but the Beatles go to A minor instead. Many sophisticated musicologists, MacDonald says, have studied this moment and written with analytical rigor about the harmonic language the Beatles employ at this moment and the different ways one might conceptualize it. But that’s all wrong, MacDonald says.

The key point is this: John and Paul were sitting in a room and each of them had a guitar on his lap. That’s the thing to remember, because every guitar player knows how much easier it is to play an A minor chord than an A major one — and, even more important, how much easier it is to riff on an A minor chord, to introduce hammer-ons and pull-offs that make the song sound better. (This is true when using standard tuning anyway — what I like to call Em7add11 tuning — which the Beatles almost always did.) Almost certainly, MacDonald says, at the moment when the A major chord would’ve been the most obvious thing in the world to play, either John or Paul went to the A minor instead — and lo and behold, it sounded cool. So they kept it.

Handmind at work.

You have to remember that neither of those guys could read music; neither of them wanted to read music. Nor did they have access to modern digital tools for music creation. What did they have? Four things:

- guitars

- ears

- hands

- musical memories

And maybe that’s Step One. If we want to reinvigorate the arts, if we don’t want culture to come to a standstill, maybe we need to start with a radical minimalism. Artists: deprive yourselves of everything except the absolutely essential tools. You can’t stream, you can’t use a DAW, you can’t look anything up online, you don’t have an iPad. You have your sensorium and you have the most basic tools imaginable — a pencil, a lump of clay, a pennywhistle or a ukelele. Go.