A Very Happy Dog.

Finished reading: Small Town Talk by Barney Hoskyns. Reading about the music of the Sixties can be fascinating, but reading about all the $$$ complications is often infuriating, and reading about the musicians' personal lives is deeply depressing. 📚

James Hill: “Eve Arnold, the wonderful Magnum photographer, used to recount a story about walking with Henri Cartier-Bresson from the Magnum office in Paris to have lunch at his apartment on the Rue de Rivoli. During the 15-minute stroll home, as he kept telling her that he was no longer interested in photography, only drawing, he took three rolls of film on his Leica.”

I’m having fun listening to The Science of Sound, from 1958. The liner notes are fun also.

I’m hitting the pause button on my weekly newsletter, but that just means that I’ll be using micro.blog as my newsletter, thanks to the cool subscribe feature. Indeed I’ve already begun posting some items of interest that I previously would’ve saved for the weekly issue.

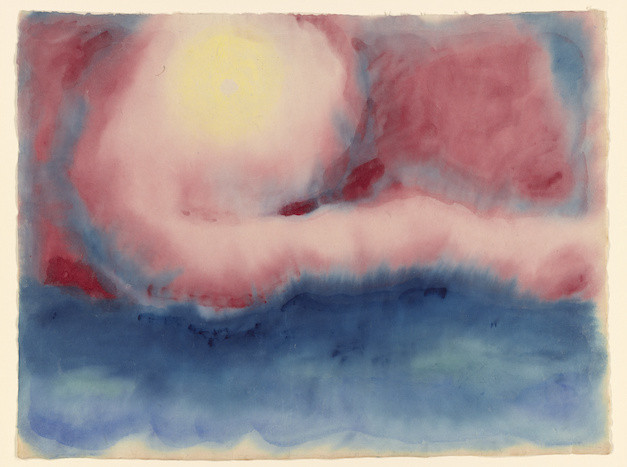

From a fascinating interview about Georgia O’Keefe’s choice of materials, especially papers.

Hilary Hahn plays the Sibelius Violin Concerto — an astonishing performance 🎵

Cabel Sasser: “Some designers are amazing at imagining things, but not as amazing at imagining them surrounded by the universe.”

Justine Bateman: “Don’t forget, AI isn’t doing this to us. People using AI to eliminate jobs, that’s who’s doing this in every sector. People really understand that concept because it’s happening in their worlds, too. … The idea that you want to use AI to make things easy for us? Go solve the homeless problem. Go use generative AI to clean the ocean. So, is generative AI coming in the entertainment business to make better films? No. It’s to more cheaply regurgitate the past. And frankly, audiences have been conditioned for this; look at all the sequels, reboots and remakes.”

I have a page for my students explaining why I won’t use ed-tech software like Canvas and Turnitin, and I just updated it to add this: Chatbots are fentanyl for the mind.

Dylan's conversion

Conversion to folk music, that is. From the 1978 Playboy interview:

PLAYBOY: Just to stay on the track, what first turned you on to folk singing? You actually started out in Minnesota playing the electric guitar with a rock group, didn't you?

DYLAN: Yeah. The first thing that turned me on to folk singing was Odetta. I heard a record of hers in a record store, back when you could listen to records right there in the store. That was in '58 or something like that. Right then and there, I went out and traded my electric guitar and amplifier for an acoustical guitar, a flat-top Gibson.

PLAYBOY: What was so special to you about that Odetta record?

DYLAN: Just something vital and personal. I learned all the songs on that record. It was her first and the songs were “Mule Skinner,” “Jack of Diamonds,” “Waterboy,” “Buked and Scorned.”

Though with Dylan you can never tell, I hope this is true. (Especially since Odetta and I share a home town.)

Twenty-five years ago I wrote an essay about Dylan that was published first in Books & Culture and then at bobdylan.com — the former of which was a pleasure to have published and the second rather disorientingly exciting. (I got paid in CDs.) I think this is the B&C version.

“It’s very tiring having other people tell you how much they dig you, if you yourself don’t dig you.” — Bob Dylan, 1965

Here’s an essay (PDF) about my adolescent years that I published 25 years ago. Not how I would write it today, but I need to respect my past self. Also, time flies.

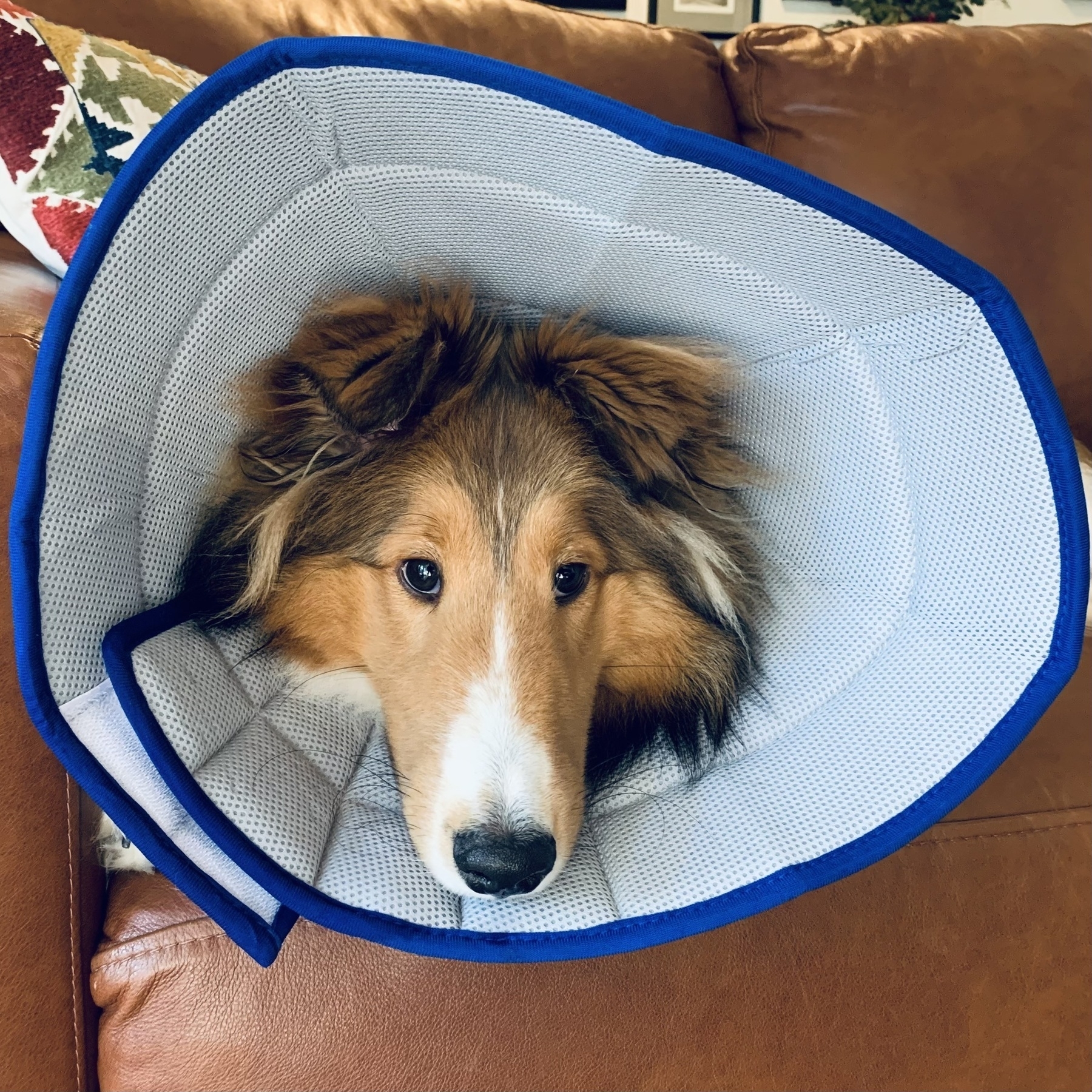

We got Angus a new e-collar and he finds it much more comfortable, though he sort of looks like he’s wearing an Easter bonnet.

outreach and generativity

Over at the Daily Nous, Alex Guerrero, a professor of philosophy at Rutgers, argues that the traditional three branches of academic work — teaching, research, and service — needs to be augmented by a fourth: outreach or engagement.

Colleges and universities are supported (1) by the general public, through government funding; (2) by students and their families, through tuition and fees; and (3) by rich people, through donations. What education and what knowledge will be pursued in colleges and universities is not set in stone; it is, rather, a function of what those three groups want and demand. If we want philosophy to be part of the education and part of the knowledge that is pursued in the years to come, we need people in those three groups to want and demand philosophy. And for people in those three groups to want and demand philosophy, we need to reach out to them, engage them, make them aware of what philosophy is and why it is wonderful and valuable. Given what philosophy is, and given our contemporary situation, that task is monumental, and must be undertaken at many different levels, in many ways. No small number of us can do it on our own. Therefore, it should be a part of all of our jobs — quite literally — to do this work.Such outreach can be accomplished in several ways:

There are obviously central enterprises: exposing children and adolescents to philosophy and serious humanities in K–12 education, for example, something that many are already doing. Writing “public facing” philosophy that appears in newspapers, broad circulation prestige venues, trade books, and so on. Creating online philosophy courses and videos and other broad access materials like podcasts. There are also more local, more intimate efforts: organizing a public philosophy week at a public library, running a philosophy club or ethics bowl team at the local high school, organizing community book groups and “meetups” to discuss philosophy, running “ask a philosopher” booths at the train station, farmers’ market, or mall. These activities bring philosophy to people outside of the academy and bring people into philosophy, giving them entry points and a better sense of what the subject is and why it is of value. They also are a lot of fun. And a ton of work to do well. And, for the most part, they are treated as outside of one’s job, falling outside of the big three: research, teaching, and service.Obviously this idea would apply to many other disciplines (most of them? all of them?) and it certainly applies to mine. When I write here on my blog, or for non-academic magazines and websites, I am certainly and quite consciously practicing such outreach — but none of it has any value in the eyes of Baylor University. My position at Baylor is wholly due to my academic work. You could of course argue that that’s as it should be, that strictly academic work is what universities ought to value and support; but for what little it’s worth, I think that’s shortsighted.

I could cite several reasons for my view. For instance, some students want to attend the Honors College here at Baylor because they have encountered the public work, the outreaching work, that I and several of my colleagues do. We can in a similar way help with the recruitment of faculty also. But I suspect that there may be other benefits to my kind of public-facing work, benefits that are more strictly academic — even if the work itself isn’t academic, or not in the familiar ways.

Consider the career of the great computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra. Cal Newport recently wrote about Dijkstra’s work habits in a post that’s interesting in several ways — but I just want to call attention to one thing: what Dijkstra did after he received a research fellowship from the Burroughs Corporation. Newport quotes one colleague of Dijkstra’s: “The Burroughs years saw him at his most prolific in output of research articles. He wrote nearly 500 documents in the EWD series.”

But hang on a minute. His entries in “the EWD series” were not in any conventional academic sense “research articles.” They were, basically, letters, originally typewritten and later handwritten with a Mont Blanc pen, which Dijkstra photocopied and mailed to colleagues. (He numbered and labeled them, and each label began with his initials, EWD, thus their familiar name. “I got a new EWD today!”) The initial recipients numbered only in the dozens, but since they had photocopiers too, it’s estimated that each EWD had hundreds or even thousands of readers.

Sometimes EWDs developed into proper research articles, but, as the home page for his archives notes, “the great majority of his manuscripts remain unpublished. They have been inaccessible to many potential readers, and those who have received copies have been unable to cite them in their own work.” The archive was created precisely in order to enable proper academic citations, since “personal communication from the author” is not a recognized form of documentation in the CS world.

So Dijkstra’s EWDs were not proper academic research, were not the sort of thing that one can put on a CV or include in a year-end report; nor were they “outreach” in Alex Guerrero’s sense, since they were directed to Dijkstra’s colleagues and peers rather than to the general public. Yet, as thousands of computer scientists over the decades have testified, the EWDs were enormously generative: they inspired and guided research throughout the field of computer science.

Universities know how to reward the dissemination of ideas through standard peer-reviewed publication; what they do not know is how to reward generativity. And, to be fair, that’s true at least in part because it’s hard to know in advance what ideas will generate other ideas, what projects other projects. It took a corporation to risk supporting Dijkstra, not knowing what the results would be; but perhaps there are expansive and stimulating thinkers in disciplines that no current corporation would care to support. Maybe that “fourth branch” should, in addition to outreach or engagement, also seek to discover and reward generativity.

The best service I could provide through this blog is to stimulate others (and not just, or even primarily, academics) to pursue ideas that I don’t have time to pursue myself, and while I don’t expect Baylor to reduce my teaching load so that I might have more opportunity to hand-write letters to twenty or thirty colleagues — or, um, blog a lot — a guy can dream, can’t he?

ChatGPT rejects any notions of creative struggle, that our endeavours animate and nurture our lives giving them depth and meaning. It rejects that there is a collective, essential and unconscious human spirit underpinning our existence, connecting us all through our mutual striving.

ChatGPT is fast-tracking the commodification of the human spirit by mechanising the imagination. It renders our participation in the act of creation valueless and unnecessary. That ‘songwriter’ you were talking to, Leon, who is using ChatGPT to write ‘his’ lyrics because it is ‘faster and easier,’ is participating in this erosion of the world’s soul and the spirit of humanity itself and, to put it politely, should fucking desist if he wants to continue calling himself a songwriter.

Oughta count.