A bluntly powerful essay by my friend and colleague Jonathan Tran:

What began as a struggle of and for the dispossessed has devolved into a culture war fixated on harms, microaggressions, and sensitivity trainings. No one can live up to the standard of being sensitive to every possible sensitivity, setting everyone up to fail. More importantly, almost none of this has anything to do with repairing and redistributing structures and systems.Nothing captures antiracism’s mission drift better than the explosive growth of its billion-dollar diversity industry, which promises to address inequality by diversifying the faces of gatekeeping institutions—the very institutions that facilitate upper-middle-class mobility precisely by leaving inequality in place. These antiracist initiatives, often staffed by well-meaning and high-minded people, bring with them all the conviction but little of the power to actually get anything done, at the end of the day achieving so little that one begins to wonder if futility was the point.

The Jellyfish Tribe - by Paul Kingsnorth:

The growing loss of faith across the West in our institutions, leaders and representatives in recent years is like nothing else I’ve seen in my lifetime. When, I wonder, did that contract begin to expire? Maybe in 2003, when the lies with which the US and UK launched the Iraq war were so blatant that even those telling them seemed unconvinced. Or perhaps when the near-collapse of the global economy in 2008 brought the real impact of Machine globalisation, which had long been felt in the poor parts of the world, home to people in the West. Or maybe in 2016, when Brexit happened and Donald Trump happened and European ‘populism’ happened, and suddenly liberal globalism was under attack in its heartlands. From then on, we learned that populism was fascism and elected presidents were Russian agents and nationhood was white supremacy and free speech was ‘hate speech’, and while we were still trying to work through all that, along came covid and we all fell into the rabbit hole forever.

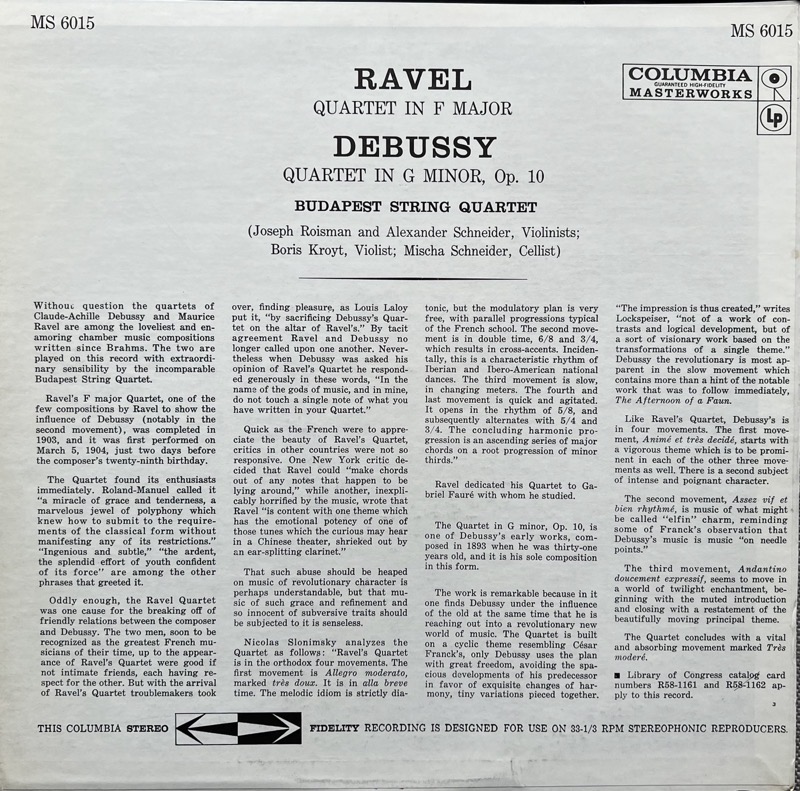

just purchased

An excellent find, in excellent condition, and for eight bucks! Also a neat little window into classical music culture ca. 1972.

I get the security concerns that have prompted the move to passkeys, but the new strategy forces us to have our smartphones on us at all times. For someone like me who wants to carry my smartphone less and less, this is a major frustration.

I’m still reading Reporting World War II: The 75th Anniversary Edition: A Library of America Boxed Set – what an extraordinary anthology of journalism, including photojournalism. The books feature a good chronology of the war and a series of useful maps. It’s a strangely immersive experience. 📚

humanism renewed

I often see quoted a line by Carl Schmitt:

The concept of humanity is an especially useful ideological instrument of imperialist expansion, and in its ethical-humanitarian form it is a specific vehicle of economic imperialism. Here one is reminded of a somewhat modified expression of Proudhon’s: whoever invokes humanity wants to cheat.

But I don’t think we can understand Schmitt’s point by quoting that sentence alone; we also need to quote the one that follows it:

To confiscate the word humanity, to invoke and monopolize such a term probably has certain incalculable effects, such as denying the enemy the quality of being human and declaring him to be an outlaw of humanity; and a war can thereby be driven to the most extreme inhumanity.

If you only quote the first sentence, then you have a version of a famous but inevitably misattributed line: “When I hear the word ‘culture’ I reach for my gun.” But Schmitt is not dismissing the very concept of “humanity”; he is making a more complicated (though still cynical) point. “Humanity” and “humanism” are “ideological instruments”: they can be and often are used as levers of power, as means by which one may gain dominance over one’s political enemies. The danger lies not in the very notion of humanity but rather in the ways that that notion is susceptible to being monopolized and weaponized by parties in power. That Schmitt does not want to do away with the notion altogether may be seen in his condemning accusation of “inhumanity.”

Given the enormous damage the reign of identity politics has inflicted on our common weal, our ability to live in peace together, what we need, I believe, is serious work to restore and renew the concept and practice of humanism. My recent essay “A Humanism of the Abyss” is a step in that direction. This is a matter I will return to — and, also, see the tag for my earlier reflections on the topic.

Stanford Law School Dean Jenny S. Martinez:

I want to set expectations clearly going forward: our commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion is not going to take the form of having the school administration announce institutional positions on a wide range of current social and political issues, make frequent institutional statements about current news events, or exclude or condemn speakers who hold views on social and political issues with whom some or even many in our community disagree. I believe that focus on these types of actions as the hallmark of an “inclusive” environment can lead to creating and enforcing an institutional orthodoxy that is not only at odds with our core commitment to academic freedom, but also that would create an echo chamber that ill prepares students to go out into and act as effective advocates in a society that disagrees about many important issues. Some students might feel that some points should not be up for argument and therefore that they should not bear the responsibility of arguing them (or even hearing arguments about them), but however appealing that position might be in some other context, it is incompatible with the training that must be delivered in a law school. Law students are entering a profession in which their job is to make arguments on behalf of clients whose very lives may depend on their professional skill. Just as doctors in training must learn to face suffering and death and respond in their professional role, lawyers in training must learn to confront injustice or views they don’t agree with and respond as attorneys.

Law is a mediating device for difference. It therefore reflects all the heat of controversy, all the pain and suffering, and all the deeply felt moral urgency of our differences in position, power, and cherished principles. Knowing all of this, I believe we cannot function as a law school from the premise that appears to have animated the disruption of Judge Duncan’s remarks -- that speakers, texts, or ideas believed by some to be harmful inflict a new impermissible harm justifying a heckler’s veto simply because they are present on this campus, raised in legally protected speech, and made an object of inquiry. Naming perceived harm, exploring it, and debating solutions with people who disagree about the nature and fact of the harm or the correct solutions are the very essence of legal work. Lively, candid, civil, and evidence-based discourse in disagreement is not just positive for our community, constituted as it is in difference, it is a professional duty. Observance of this duty matters most, not least, when we are convinced that others haven’t.

I think Dean Martinez has navigated this mine field about as well as it could be navigated, and in the process has made some vital salient points about the nature of legal education — and of true education more generally.

Currently reading: The Earthsea Quartet by Ursula K. Le Guin 📚

Bison at Caprock Canyons State Park in the Texas panhandle, which I visited a couple of weeks ago. With that experience in mind I was glad to see this essay: “The Return of the Bison.” And yes, though you may not be able to see them in that photo above, there really are canyons at Caprock Canyons:

the arbiters

The impossible job: inside the world of Premier League referees: An excellent in-depth study. None of the problems identified here are easily addressed, but I think the first steps should be:

First: retrospective punishment for players who (a) surround the ref to intimidate him and (b) simulate being fouled. And not fines — the players are too rich to care about fines. I think the best option would be for players found guilty in these matters to begin their next match with a yellow card. That may seem strong, but there is a deeply-ingrained culture of bullying and deceiving that needs to be addressed.

Second: eliminate VAR. Just get rid of it. Many years ago my persistent back pain led me to consult a surgeon, who told me that one-third of the people who had the operation I needed got relief from their pain, one-third were left unchanged, and one-third experienced increased pain. VAR is like that; and even when its decisions are correct it makes every single match in which it’s used worse, because fans don’t have any idea whether to celebrate a goal or not — it might be overturned. Almost any idea — including adding a second referee — would be preferable to VAR.

One more thing about VAR: it’s even less reliable than people think, because one of its weaknesses is almost never noted. When VAR is looking at a potential offside, we’re always shown the players at the offside point and the line that indicates whether the attacking player is ahead of the defender or even with him. What no one looks at is the ball: Has VAR captured the precise moment at which the ball is struck? Typically you can’t tell, because the ball itself obscures the player’s foot. (Here’s an example, from the Premier League website.) VAR might have frozen the video at the precise instant that the player’s foot strikes the ball, but that’s highly unlikely. It’s much more likely that the video is stopped a fraction of a second early or a fraction of a second late; and that might make the difference between whether a player is offside or not. VAR is thus tasked with making decisions that it simply cannot make. Be done with it, I say!

Treat time!

as it must to all men...

When Charlie Watts died in August of 2021, I wrote: “This feels like a big one, and is certainly a harbinger of things to come.” I didn’t know at the time that Damon Linker had written two years earlier about “The coming death of just about every rock legend.”

But it’s not just musicians, is it? Consider some of our most famous film directors:

- Woody Allen is 87

- Francis Ford Coppola is 83

- Werner Herzog is 80

- David Lynch is 77

- George Lucas is 78

- Terrence Malick is 79

- George Miller is 78

- Hayao Miyazaki is 82

- Martin Scorsese is 80

- Ridley Scott is 85

- Steven Spielberg is 76

- Wim Wenders is 77

(Obviously, other distinguished names could be added to the list.) Interesting how closely their ages correlate with those of the great rock stars — though the rock stars became famous a decade or more earlier. Won’t be terribly long before we’re saying “There were giants on the earth in those days.”

It would be very difficult to determine the Platonic ideal of a Steven Wright joke, but I think it might be: “What’s another word for ‘thesaurus’?”

Heads up: the Bono & Edge Tiny Desk concert is just fantastic.