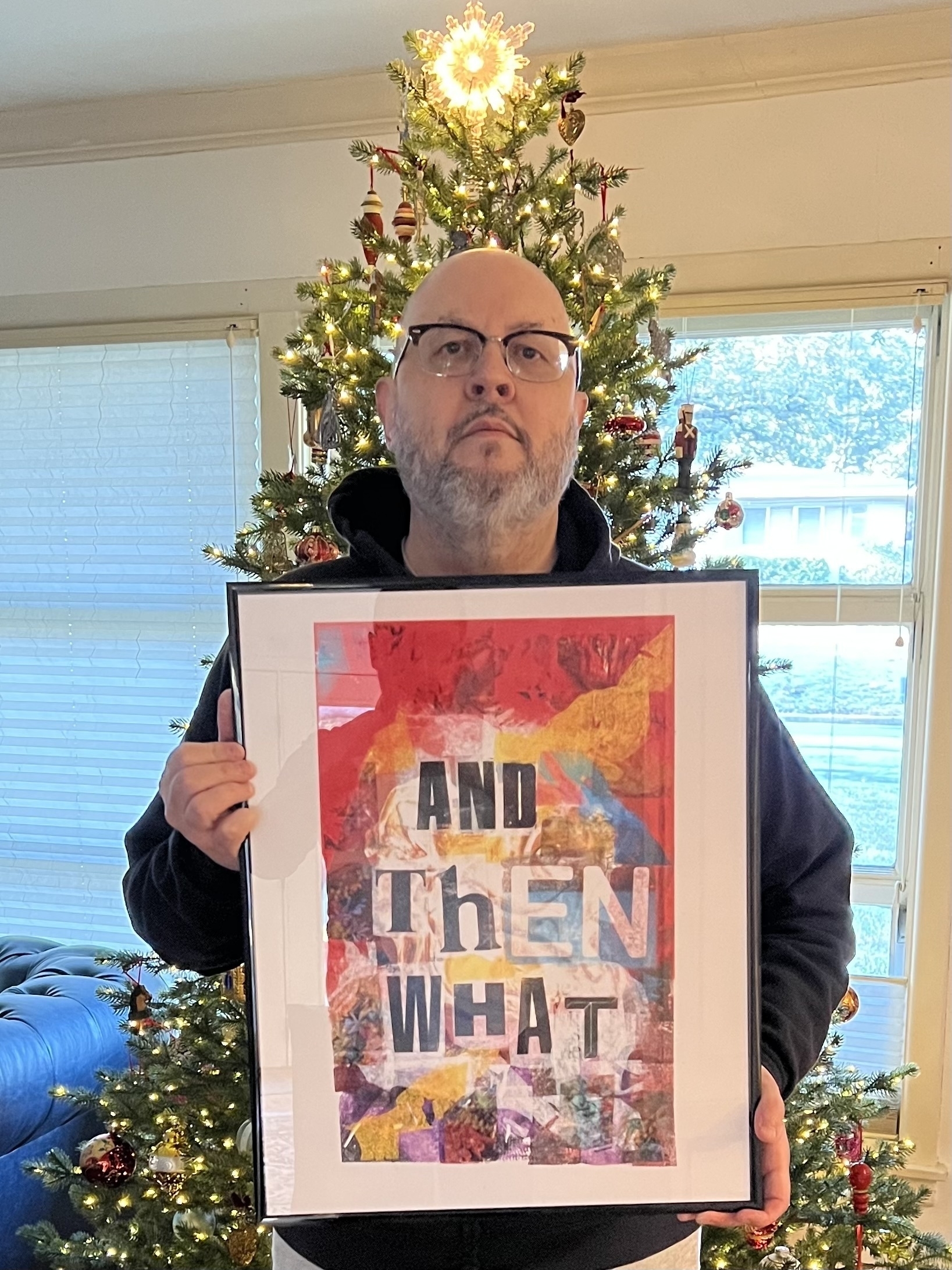

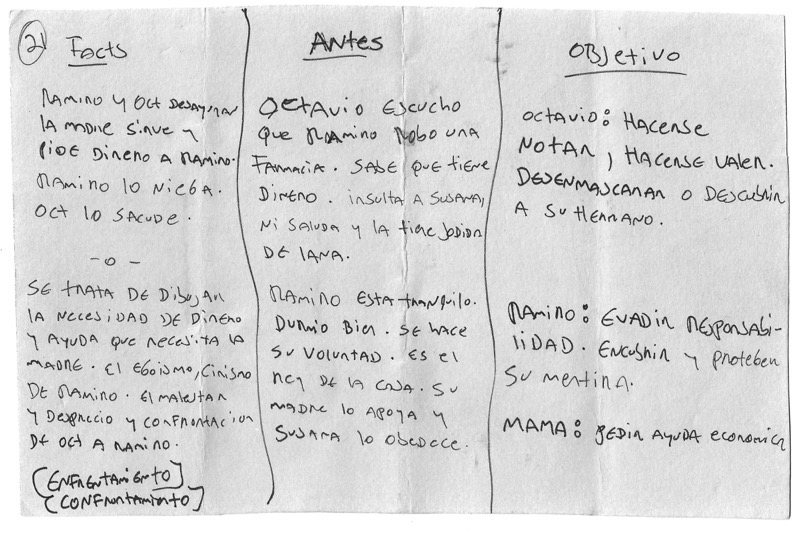

movie cards

When preparing to shoot a scene, the film director Alejandro Iñárritu prepares note cards to help him organize his thoughts. ”During the production of a film, it’s easy to lose track of and forget the original intentions and motives that you had three years ago in your head and that are always so important.” Moreover, “As Stanley Kubrick once said, making a movie is like trying to write poetry while you’re riding a roller coaster. When one is shooting a film, it feels like a roller coaster, and it’s much more difficult to have the focus and mental space that one has during the writing or preparation of a film.”

So to forestall these problems, Iñárritu grabs a blank note card and divides it into columns, usually featuring six categories:

- He begins with the facts. “I try to write down the facts in a neutral way. What is happening in this particular scene?”

- “The second part is that I try to imagine what happened immediately preceding the moment in question. Where have the characters come from?”

- “The third column details the ‘objective.’ What is the purpose of this scene? … Here I try to dissect the objective of the scene as a whole and what it’s about, as well as the objective of each of the characters who appear…. Each character has a need, and it’s important for me to know what it is.”

- “The fourth part of these cards — the ‘action verb’ column — is particularly difficult … and extremely helpful, too, in further clarifying a character’s objective so that the actor can execute the scene. If one character wants something from another character, one way of achieving the goal is by seducing the other character. Another way is by threatening him. Another way is by ignoring or provoking him. Within a scene, there can also be several action verbs — these kinds of transitions in tactics for obtaining the same objective are important because they bring a scene to life and add color to it.”

- “The subtext … is often almost more important than the text. The text can often be contrary to the subtext, and the subtext is what should be very clearly understood. In other words, if one person says to another, ‘Go away, I don’t want to see you again,’ it is very possible that what they really mean is ‘I need you now more than ever.' The words we use can often oppose what we feel, and I believe that acknowledging this human contradiction can help give great weight to a performance.”

- Finally, the ‘as if' column. There are two ways I believe one can take on a performance — one is through the actor’s own personal and emotional experience, applied to a scene through an association with it, and the other is through imagination.… I have been in situations where an actor, at a given moment, lacks imagination for some personal reason or does not have emotional baggage that he can refer to. In such a case, I sometimes like to have an image that I can leave with an actor or actress. Our body is the master. Sometimes, with a physical or sensorial experience (a burn, cold, etc.), the actor or actress will know already how that feels, and that can help in channeling that feeling.”

markets and economies

[Rusty] Reno’s ongoing mistakes are derived from his first mistake — the straw-man claim that market orthodoxy seeks to value everything solely on market principles. This simply is not true. A rigorous defense of the price mechanism in how goods and services are transacted does not require any such framework for how we understand truth, beauty, goodness, and love. Believing in the transcendent things and believing in them with the depth and breadth that moral enlightenment and spiritual nourishment provide makes us better market actors. That Reno and I are living in a time where the clear and unmistakable maladies of culture are evidenced in the marketplace does not make the forum for our observation the cause of what we observe. I know it is frustrating, unsatisfying, and in many cases, unacceptable, but the moral deterioration of society evidenced in various aspects of our marketplace are the fruits of idolatry, low regard for family, disdain for neighbor, and a general abandonment of Ten Commandments ethics. Markets cannot assure regard for neighbor or beauty, but a disdain for markets can assure us of impoverished conditions for our neighbors and a limited landscape for the creation of beauty.

Bahnsen makes a point worth considering here but my general position with regard to markets is closer to Reno’s. (My general position as opposed to my specific policy preferences, which are very far from Reno’s.)

Bahnsen makes a distinction between culture and markets that’s simply not sustainable. Markets are part of culture — i.e. they’re among the things that human beings collectively do — and we have plenty of evidence that the people who are most determined to make money in the markets tend also to exploit the weaknesses of the other parts of culture for their gain. That is, market thinking is like kudzu: a powerfully invasive species that can conquer an entire ecosystem if it is not forcibly restrained. The logic of markets always wants to extend its reach into sphere of culture in which it does not belong, and its spread should be closely observed and resisted.

As Augustine taught us long ago, we live in a single culture governed by what Wendell Berry calls two economies in tension with one another. (Perhaps some readers will know what I mean if I say that we live in a space like the one doubly occupied by Besźel and Ul Qoma. Which reminds me that I need to write something about that fascinating book.) At least some degree and kind of sphere sovereignty is suggested by Jesus’s instruction that we render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s. The problem is that capitalist kudzu doesn’t respect such distinctions, which is how we get surveillance capitalism and, ultimately, metaphysical capitalism. (See the tags at the end of this post.)

The market is not something other than culture; it is an element of culture that wants to become the whole thing, as kudzu wants to spread and as water wants to run downslope. If a culture is going to thrive this tendency must be resisted, and such resistance requires constant vigilance and political imagination — both of which are in very short supply.

P.S. The whole matter of alternative (and possibly irreconcilable) economics is central to thinking wisely about out cultural moment. In addition to the link above to Wendell Berry on the “two economies,” see also:

- Ruskin and the economy of the affections

- Metaphysical capitalism against the gift economy

- Ivan Illich and the possibility of the Vernacular Republic

UPDATE: “So what lessons, if any, remain from Polanyi for us today? At the broadest level of his argument, the recognition that there is no bright-line division between the economy and society continues to be an important, if still underrecognized point. Recognizing it explicitly would improve policy discussions all around.”

Long coveted on vinyl!

How Would You Prove That God Performed a Miracle?:

J. Ayodeji Adewuya is a professor of New Testament at the Pentecostal Theological Seminary in Tennessee. He saw his share of miracles in his home country, Nigeria — including, he believes, the raising of his stillborn infant son after he spent 20 minutes shouting and pacing the room in prayer. “I joke, you don’t really need to pray the Lord’s Prayer, ‘Give us our daily bread,’ when you have everything provided by Walmart and your fridge is full,” he told me. “When you’re in a place where you have nothing, the only thing you can do is depend on God, and at that point you’re expecting something. The average white evangelical Christian doesn’t expect anything.”

Western skeptics have disregarded witness testimony from places like Nigeria at least since David Hume complained in his 1748 essay on miracles that “they are observed chiefly to abound among ignorant and barbarous nations.” Such dismissal is more awkward for 21st-century secular liberals, who often say that Westerners should listen to people in the Global South and acknowledge the blindnesses of colonialism. “Some people claim that the best thing to do is to listen to people’s experiences and learn from them,” Dr. Chinedozi said. “Yet these people will be the first to find a way to disprove experiences in other cultures and contexts.”

He’s not wrong.

Christmas Eve lunch with my dear ones. ❤️

the friendliness of objects

Repair [at an earlier stage of our culture] was not so much a habit as an honoured custom. People respected the past of damaged things, restored them as though healing a child and looked on their handiwork with satisfaction. In the act of repair the object was made anew, to occupy the social position of the broken one. Worn shoes went to the anvil, holed socks and unravelled sleeves to the darning last — that peculiar mushroom-shaped object which stood always ready on the mantelpiece.

The custom of repair was not confined to the home. Every town, every village, had its cobbler, its carpenter, its wheelwright and its smith. In each community people supported repairers, who in tum supported things. And our surnames testify to the honour in which their occupations were held. But to where have they repaired, these people who guaranteed the friendliness of objects? With great difficulty you may still find a cobbler — but for the price of his work you could probably buy a new pair of shoes. For the cost of 15 digital watches you may sometimes find a person who will fix the mainspring of your grandfather's timepiece.

The truth is that repair, like every serious social activity, has its ethos, and when that ethos is lost, no amount of slap-dash labour can make up for it. The person who repairs must love the broken object, and must love also the process of repair and all that pertains to it.

I am greatly taken by the way Scruton frames the work of repair here, especially the idea that the impulse to repair arises from and is sustained by love — and that the particular form of love at work here is friendship. By repairing the things of this world we exhibit friendship towards them — and they become friends to us in return.

People need things, and things need people.

The critical moment of their mutual support is the moment of breakdown. Suddenly, the object on which everything depended — the car, the boiler, the drain, or the dinner suit — is unusable, and you contemplate its betrayal in helpless unbelief. It is some time before you overcome your self-pity enough to recognise that its need is greater than yours.

We get angry at broken things, and want to throw them out — and this impulse often governs us even when the broken thing is not a car or a drain but democracy or education. (Maybe democracy and education are not objects but rather hyperobjects.) But what if we were to think not that our education has betrayed us but rather that its need is greater than ours? What if we were to think that towards even something so vast and complex we have the obligations of friendship? And, if we meet those obligations, perhaps we could even enjoy the benefits of friendship.

Ross Douthat’s Advent-themed newsletter quotes Auden and, um, me – so you know it’s something special!

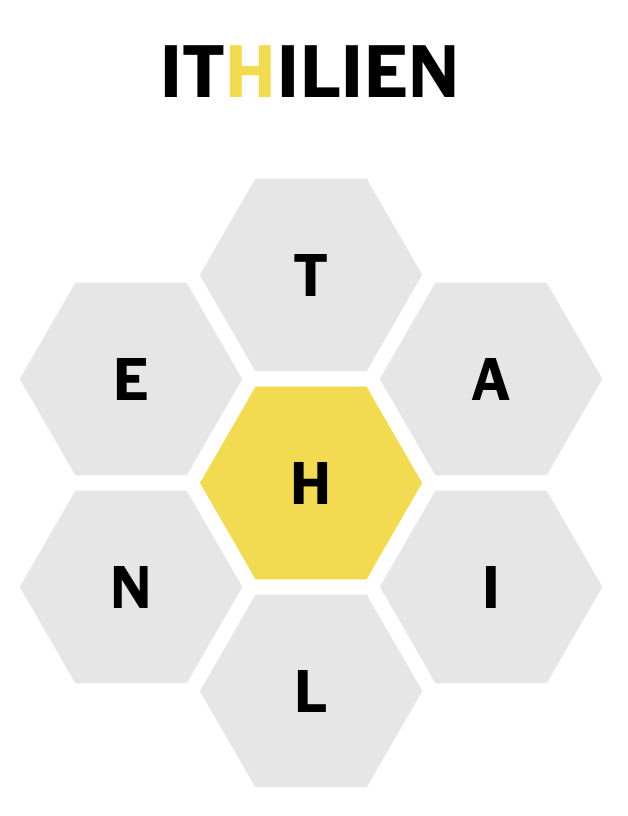

I’d like a version of Spelling Bee in which the only acceptable words are proper names from Tolkien’s legendarium.

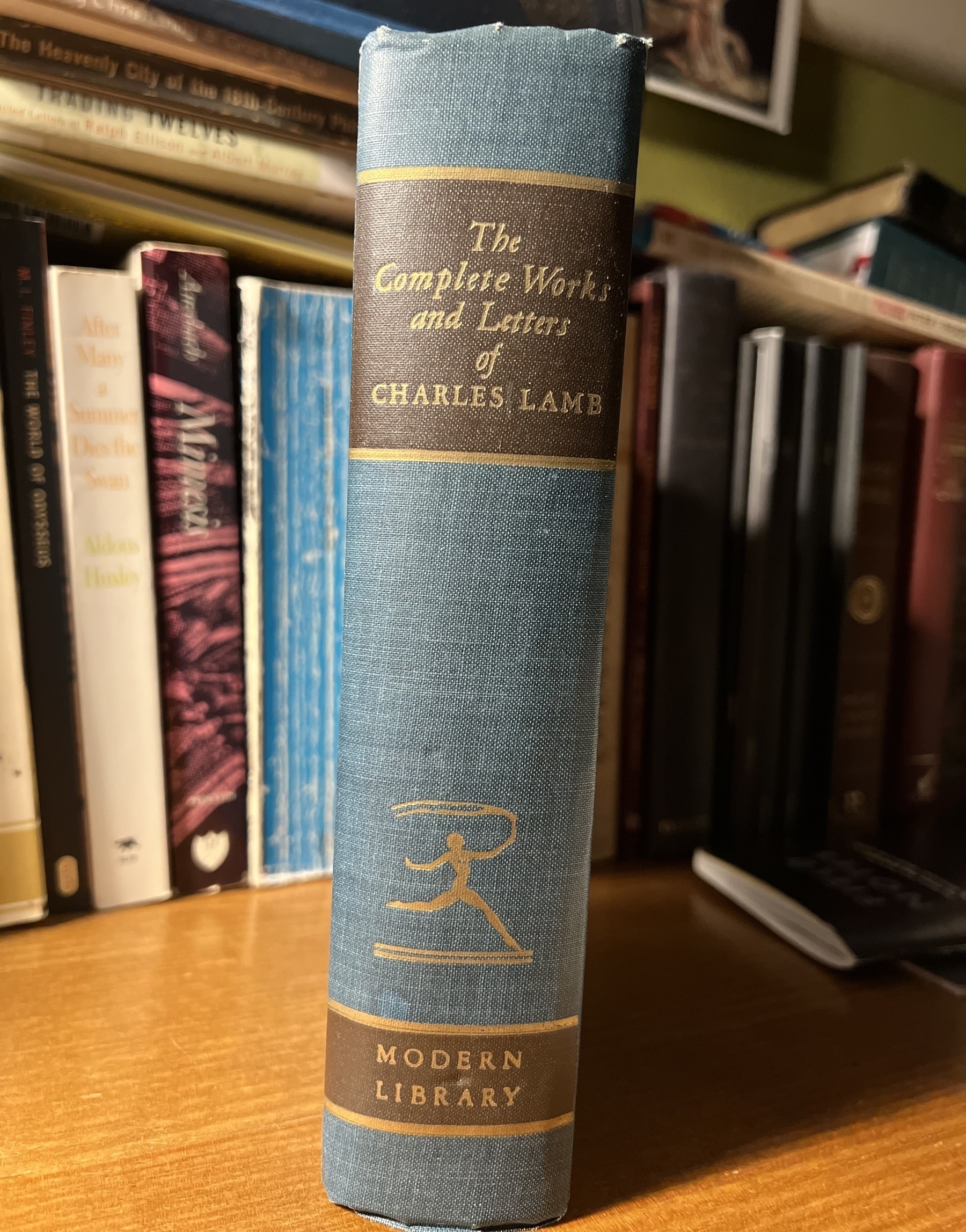

Currently reading 📚

The difficulty of Donne's work had in it a stark moral imperative: pay attention. It was what Donne most demanded of his audience: attention. It was, he knew, the world's most mercurial resource. The command is in a passage in Donne's sermon: ‘Now was there ever any man seen to sleep in the cart, between Newgate and Tyburn? Between the prison, and the place of execution, does any man sleep? And we sleep all the way; from the womb to the grave we are never thoroughly awake.’ Awake, is Donne's cry. Attention, for Donne, was everything: attention paid to our mortality, and to the precise ways in which beauty cuts through us, attention to the softness of skin and the majesty of hands and feet and mouths. Attention to attention itself, in order to fully appreciate its power: Our creatures are our thoughts, he wrote, ‘creatures that are born Giants: that reach from East to West, from earth to Heaven, that do not only bestride all the sea and land, but span the sun and firmament at once: my thoughts reach all, comprehend all.’ We exceed ourselves: it's thus that a human is super-infinite.

What happens when engineers stop thinking of their interests as fundamentally aligned with the companies' owners and management, and develop their own class consciousness? Tech companies are not pursuing automation purely out of intellectual interest; they are trying to solve looming labor problems that can no longer be ignored.

All of this is the backdrop for these companies moving away from human customers and human workers, towards AI solutions, invisible infrastructure, and business, government, or military contracts. The ideal for a tech company in 2023 is either docile humans ready to consume what they've been given, or better still, no humans at all.

Good to read this in conjunction with Ted Gioia’s post “Has TikTok Already Peaked?”

There appears to be a circle of mutual support between political correctness, technocratic administration, and the bloated educational machinery. Because smartness (as indicated by educational credentials) confers title to rule in a technocratic regime, the ruling class adopts a distinctly cognitivist view: virtue does not consist of anything you do or don’t do, it consists of having the correct opinions. This is attractive, as one may then exempt oneself from the high-minded policies one inflicts upon everyone else. For example, the state schools are turned into laboratories of grievance-based social engineering, with generally disastrous effects, but you send your own children to expensive private schools. You can de-legitimise the police out of a professed concern for black people, and the explosion of murder will be confined to black parts of the city you never see, and journalists are not interested in. In this way, you can be magnanimous while avoiding the moral pollution and that comes from noticing reality.

I keep thinking about this piece Matt wrote two years ago, especially its conclusion: "If the ideal of a de-moralised public sphere was a signature aspiration of liberal secularism, it seems we have entered a post-secular age. Populism happened because it became widely noticed that we have transitioned from a liberal society to something that more closely resembles a corrupt theocracy.”

Angus and his mama, Gypsy.

Currently reading: Selected Stories of Anton Chekhov 📚