what a loss

We just watched To Be or Not To Be for the first time in a while. What an extraordinary movie; I don’t know of a film more tonally complex.

Jack Benny is Jack Benny — which is a high compliment — but Carole Lombard is utterly marvelous in what would prove to be her final film; she died in a plane crash just a few weeks after completing the filming — they had wrapped principal photography on Christmas Eve 1941. It’s one of her finest performances: the moment when she swooningly murmurs “Heil Hitler” is transcendently great, though you have to see it in context to know what I mean. (FWIW, I think her pinnacle for a complete film is My Man Godfrey.) This loss to acting hurts more than most because Lombard was so gifted that she would have continued to be a star, in varying roles and styles, for decades to come. She was only thirty-three when she died. A one of one.

In the spring, when the weather is (hopefully) warm and wet, a tree will grow rapidly, forming large, porous cells known as “earlywood.” Later, as the weather cools, it will grow in smaller, more tightly packed cells known as “latewood.” You can spot the difference when looking at a tree’s rings: earlywood appears as light-colored, usually thick, bands, while latewood shows up thinner and darker. What doesn’t show up in the rings is the dormant period — the winter season, when the tree doesn’t grow at all, but waits patiently for spring.

I think this is a useful metaphor for thinking about how we grow, too. There are times and seasons when the conditions are right for earlywood — for big, galloping growth, where you learn a lot in short order. This is often the case when you first step into a new role, or take on a new and challenging project, or start at a new organization. But those periods of rapid growth are often (and ideally) followed by periods when the growth is slower, more focused, moving in short and careful steps instead of giant leaps. These latewood periods are when the novelty of a new situation has worn off, and the time for reflection and deep-skill building arrives.

beyond persuasion

art, not argument | sara hendren:

I have thus far assembled a body of work that lists between the two poles of poetry and philosophy, and between significance and utility: some work that looks for pragmatic solutions to problems, and some work that raises and suspends questions, indefinitely. Some work that reframes the status quo in order to persuade. And some work that aims for expressive power above all — paradox and juxtaposition.

One thing I’ll say, though, about 2023 and beyond, as I head into my 50s: I mostly want to make art, not arguments.

A big Yes to this from Sara.

Recently I was reading Minds Wide Shut by Gary Saul Morson and Morton Schapiro, and while I venerate GSM just this side idolatry, I don’t think the book quite works as intended. At the risk of oversimplification, I’ll say that its core argument is (a) that our culture is dominated by a set of fundamentalisms — “At the heart of any fundamentalism, as we define it, is a disdain for learning from evidence. Truth is already known, given, and clear” — and (b) that the fundamentalist mindset is incapable of persuasion, of bringing skeptics over to its side.

All of which is true, but (and this is a major theme of my How to Think) what if people don’t want to persuade others? What if they don’t just hate their Repugnant Cultural Other but need him or her in order to define themselves and their Inner Ring? As I read Minds Wide Shut I kept thinking that the authors needed to persuade people of the value of persuasion. But that way an infinite regress lies.

I think what Sara is suggesting is that those of us who want to see a different world need to be better at showing rather than telling, presenting rather than directly persuading. Sara’s formulation, “work that reframes the status quo in order to persuade,” is useful, I believe. You persuade not by persuading but by reframing, by (as Ezra Pound said) making it new, by (as Philip the apostle did) saying “Come and see.”

two kinds of work

Almost forty years ago now, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote to a New York Times reporter to respond to critiques of his work and himself, most revolving around accusations of antisemitism. The whole article is interesting, but I am especially fascinated by the last sentence quotes from his letters:

My task is to write true historical research on the Russian Revolution, beyond that it's not so important to me whether my books are accepted precisely in this decade and precisely in this country.

Solzhenitsyn not only said this but, I think, truly believed it. He possessed a serene confidence that sooner or later his work would be recognized as both great and necessary, and if that recognition happened to come later rather than sooner — perhaps even long after this death — he didn’t mind.

This strikes me as something that every writer ought to know about himself or herself: Am I writing for Now or for Keeps? Is it my role to shape my own moment, or to write primarily for those who might benefit from what I have to say even if they live after I’m gone? Of course, for many writers there’s not really an option: If you’re writing to pay your bills, then you have to write for Now whether you like it or not.

I guess I’d like to have it both ways: To write for my contemporaries, to try to do my very small part to light candles and repair my corner of the world, but also to hope that I’ll have readers later on. But maybe you can’t have it both ways. (I wonder if there are examples of writers who thought that their work was immediate and ephemeral … but turned out to be wrong.)

I’ve got some advice for people who might consider moving from Twitter to micro.blog — with links to other posts. (Did that a while back, but I’ve been sharing it with disaffected tweeters.)

Currently reading: Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne by Katherine Rundell 📚

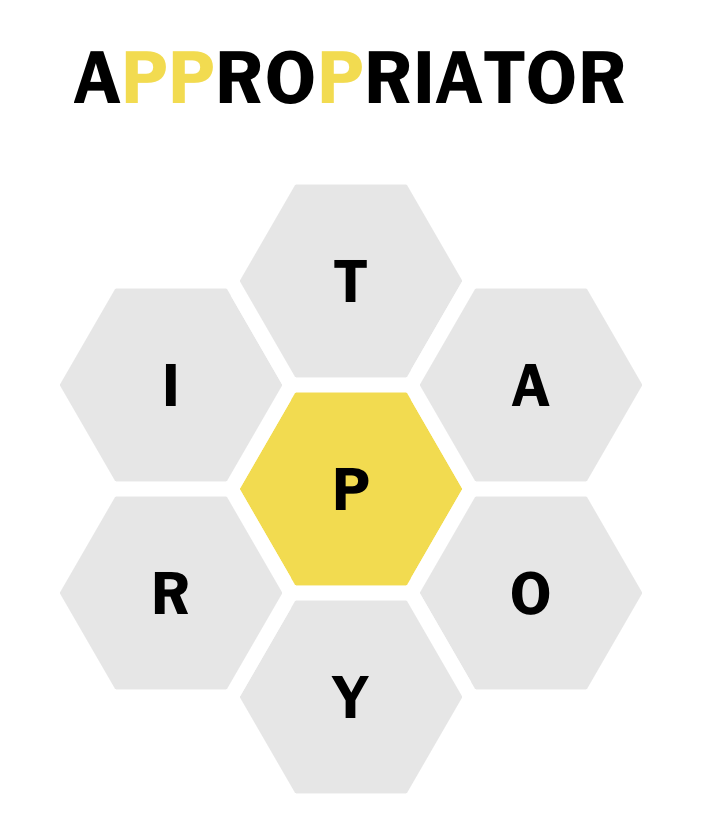

the age of taipa

I don’t want to ask whether pop music is worse than it used to me, because that’s an unanswerable question — for several reasons. But some things we can certainly say:

- Lyrics are getting more repetitive

- Songs are becoming harmonically and structurally simpler

- Recordings have become more compressed and louder, with less dynamic range

- The dominance of streaming has led to shorter songs with front-loaded choruses

All this is clearly established. Now, maybe you like this kind of music, and if so, you should definitely be you. I have a question, though: Is there a connection between these developments in recorded music and the increasing prevalence of listening to songs at double-speed?

A Japanese dictionary publisher has just chosen its Word of the Year for 2022: taipa.

The word kosupa, an abbreviated form of “cost performance” meaning “value for money,” has become a standard part of the Japanese language. Dictionary publisher Sanseidō chose a variation on this theme, taipa, or “time performance,” as its word of the year for 2022.

Taipa is used for talking about efficient use of time, and is particularly associated with the members of Generation Z, born roughly between 1995 and 2010. In search of optimum “time performance,” they might watch films and drama at double speed or via recut versions that only show major plot points, and skip to the catchy parts of songs.

For these zoomers, learning to make the best use of their time is the only way to save themselves from drowning in an ocean of online content and to keep up with friends’ conversations.

Maybe people are ready to get through music as quickly as possible because — well, because there’s not a whole lotta there there. If a song has a basic three- or four-chord structure, with no intro and no bridge, and has simple and simply repeated lyrics, then, really, why would you want to listen for more than 30 seconds, or at anything less than double-speed? I mean, why take five minutes to eat a cracker? (Even if it’s a tasty cracker.)

And maybe the movies tell a similar story: given the dominance of sequels, which feature characters we already know and don’t need to see developed, why not watch at an accelerated rate, or just skip to the fight scenes? It’s not like there’s anything else going on that would be of interest.

So maybe when people practice taipa they’re responding rationally to what’s being offered them.

Still, it must be said: taipa isn’t “efficient use of time.” Instead, it’s about the worst use of one’s time, especially one’s leisure time, that I can imagine. There are no canons of “efficiency” that apply here unless you think that there’s some kind of value in watching more movies and listening to more music, regardless of quality or interest. And if you think that you’re nuts — as I have recently suggested. As I said in that post: If you’re accelerating the rate at which you listen and watch, what are you trying to get to?

What’s being offered you isn’t always what’s best for you. If you’re worried about “drowning in an ocean of online content” you can get out of the ocean. (You might even find some new friends who have done the same. You could chill together on the beach, in the sunshine.) Remember this: the past is an always-available counterculture. There’s a great wide world of music and movies and books available to you, and you can use them to retrain your mind and spirit to a different and healthier pace.

It’s a good time to remember Hilaire Belloc’s Christmas card.

No Other Options — The New Atlantis:

One of the greatest reasons for concern is the sheer scale of Canada’s euthanasia regime. California provides a useful point of comparison: It legalized medically assisted death the same year as Canada, 2016, and it has about the same population, just under forty million. In 2021 in California, 486 people died using the state’s assisted suicide program. In Canada in the same year, 10,064 people used MAID to die.

Important people — prominent politicians, physicians, and judges — promised Canadians that their rights to autonomy would be expanded. But the picture that emerges is not a new flowering of autonomy but the hum of an efficient engine of death.

It is quite remarkable to hear from doctors and other medical practitioners who find great satisfaction in killing their patients.

This is Angus. He’ll be joining our family in a couple of weeks. We’re chuffed.

I think the puzzlemakers exclude some words simply because they’re too big.

I just posted an update for my Buy Me a Coffee supporters.

I’m a little nervous about starting this microcast series on Jesus, because I’m not good at it yet – but I hope to improve as I go along. Nothing ventured, nothing gained. And Wavelength is a fantastic tool for making microcasts. Thanks for that, @manton!

I’ll believe in AI when I can say, “Hey Siri, please hide from me all references to AI. Also every conversation in which journalists snark at other journalists. And, no references to Twitter or Mastodon.”

defining immortality down

Digital Eternity Is Just Around the Corner:

As these technologies develop and become more accessible, they will increasingly be used in combination, creating “intelligent avatars” of ourselves that continue to “live” long after we have died. We are seeing the beginnings of this with the metaverse company Somnium Space, whose Live Forever mode allows users to create “digital clones” built from data they have stored while alive, including conversational style, gaits, and even facial expressions.

This sense of immortality may be reassuring, but there is a catch. AI avatars will rely on us feeding their algorithms a huge amount of personal data, accumulated through the course of our lives. If we want our digital selves to live on, this is the exchange we must accept: that the unfiltered beliefs and opinions we express today may not only be archived, but consequently used to build these posthumous personae. In other words, we can have a voice in the afterlife, but we cannot be certain about what it may say. This will force us to reconsider how our behaviors today might influence digital versions of ourselves set to outlive us. Faced with this prospect of virtual immortality, 2023 will be the year we broaden our definition of what it means to live forever, a moral question that will fundamentally change how we live our day-to-day lives, but also what it means to be immortal.

Notice how the quotes around “live” in the first paragraph disappear in the second. Notice also — this is universal in such discourse — the unexamined “we”: "2023 will be the year we broaden our definition of what it means to live forever.” Depends on who “we” are, I think. I for one am not interested in broadening my definition of what means to live forever in such a way that it isn’t living and doesn’t last forever. But you be you!

There’s a powerful passage from C. S. Lewis’s autobiography Surprised by Joy:

I had recently come to know an old, dirty, gabbling, tragic, Irish parson who had long since lost his faith but retained his living. By the time I met him his only interest was the search for evidence of “human survival.” On this he read and talked incessantly, and, having a highly critical mind, could never satisfy himself. What was especially shocking was that the ravenous desire for personal immortality co-existed in him with (apparently) a total indifference to all that could, on a sane view, make immortality desirable. He was not seeking the Beatific Vision and did not even believe in God. He was not hoping for more time in which to purge and improve his own personality. He was not dreaming of reunion with dead friends or lovers; I never heard him speak with affection of anybody. All he wanted was the assurance that something he could call “himself” would, on almost any terms, last longer than his bodily life.

Whenever I read about someone who sees a technological route to immortality I think about this “ravenous desire for personal immortality” combined with “a total indifference to all that could, on a sane view, make immortality desirable.” So you want a digital imitation of yourself to live on after you die. But why?

Current listening: Yo La Tengo, Fakebook ♫ (a grossly underrated record)

If your Christmas season doesn’t include a viewing of The Shop Around the Corner, it really really should. 🎞

‘Luddite’ Teens Don’t Want Your Likes - The New York Times:

For the first time, she experienced life in the city as a teenager without an iPhone. She borrowed novels from the library and read them alone in the park. She started admiring graffiti when she rode the subway, then fell in with some teens who taught her how to spray-paint in a freight train yard in Queens. And she began waking up without an alarm clock at 7 a.m., no longer falling asleep to the glow of her phone at midnight. Once, as she later wrote in a text titled the “Luddite Manifesto,” she fantasized about tossing her iPhone into the Gowanus Canal.

WE’VE BEEN WAITING

WE KNEW YOU’D COME