The Struggle To Be Human - by Ian Leslie - The Ruffian:

Whether it’s music, movies or politics, we seem to be creating a world more amenable to AI by erasing more and more of what makes us, us. Even if we think we have got the better of this deal up until now, we shouldn’t assume we always will. A little resistance is prudent. The bar for being human has just been raised; the first thing we should do is stop lowering it.

The link in the previous post goes to a current Penguin edition, but I’m reading the copy I bought and read 40 years ago (but have since mostly forgotten).

Currently reading: In Patagonia by Bruce Chatwin 📚

In my experience — and I do have some experience with this phenomenon — when a journalistic outlet responds to criticism by saying “We stand by our story,” that always means that (a) they know they have been caught red-handed in either dishonesty or incompetence, (b) they cannot stage a proper defense of their work, but (c) they are unwilling to confess their shortcomings.

Whaddya mean that’s not a word? It’s my gamer handle!

DHH argues that European nations should pursue digital sovereignty. I think this is right. So far the idea of a global internet has meant primarily an American internet, and I believe (a) it would be good for other nations to declare their independence from the American tech behemoths, and (b) it would be good for my country to be reminded that we cannot dictate technological and moral terms to the rest of the world.

I like having a corkboard.

common ground and its enemies

From the More in Common report on the History Wars:

[M]ore than twice as many Democrats agree that all students should learn about how the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution advanced freedom and equality than Republicans think (92 percent versus 45 percent). Similarly, about twice as many Democrats believe students should not be made to feel guilty or personally responsible for the errors of prior generations than Republicans think (83 percent versus 43 percent). […]

[T]he proportion of Republicans who agree Americans have a responsibility to learn from our past is three times more than Democrats perceive it to be (93 percent versus 35 percent). Similarly, more than twice as many Republicans think schools should teach our shared national history as well as the history of specific groups such as Black, Hispanic and Native Americans than Democrats think Republicans believe (72 percent versus 30 percent).

Similarly, a while back I wrote that we don’t disagree as much about free speech as most people believe we do.

One of my most vital convictions is summed up in this post: “Wondering how to decide what to read? Here’s a simple but effective heuristic to cut down the choices significantly. Ask yourself one question: Does this writer make bank when we hate one another? And if the answer is yes, don’t read that writer.” Americans have these wildly distorted views of people whom they perceive to be their political enemies because so many journalists and talking heads enrich themselves through stoking hatred. Those people should be utterly shunned.

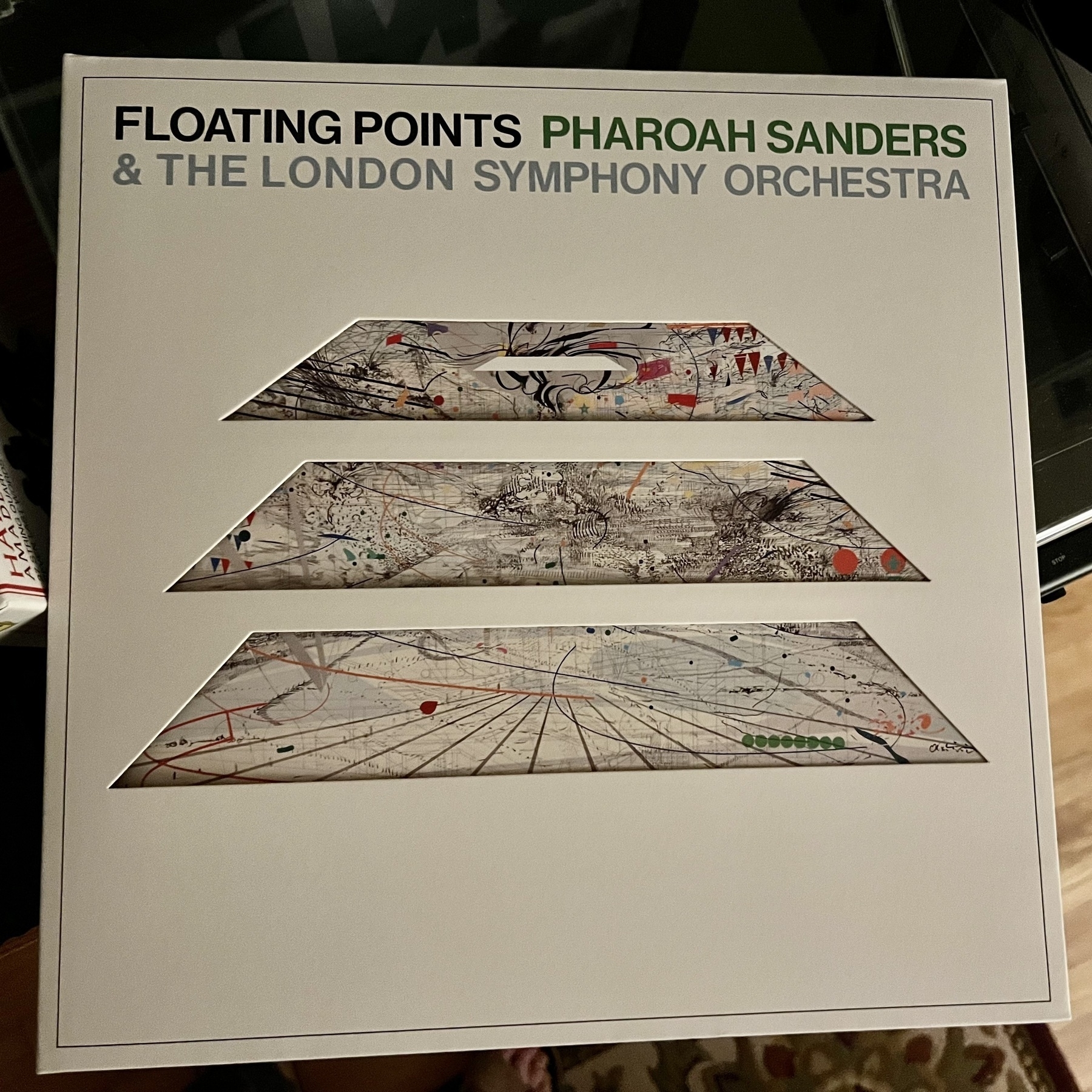

Currently listening ♫

I’ve already been lectured about the dangers of how using [Lensa] implicates us in teaching the AI, stealing from artists, and engaging in predatory data-sharing practices. Each concern is legitimate, but less discussed are the more sinister violations inherent in the app, namely the algorithmic tendency to sexualize subjects to a degree that is not only uncomfortable but also potentially dangerous.

Who could have known?

imagined railways

Matt Yglesias thinks that Amtrak should focus all of its efforts on bringing high-speed rail to the Northeast Corridor, because of course he does. But the distances between those cities are sufficiently small that the speeds don’t matter as much. What this country really needs is high-speed rail connecting more widely-spaced cities. Consider: Houston ➡ Austin ➡ El Paso ➡ Albuquerque ➡ Phoenix ➡ Los Angeles. Or, even more plausibly: San Antonio ➡ Austin ➡ (Waco?) ➡ Dallas ➡ Oklahoma City ➡ Kansas City ➡ Des Moines ➡ Chicago. I don’t think I’m alone in seeing high-speed connections among these cities as dramatically preferable to air travel.

the blog as a seasoned technology

For several years now I’ve been writing about the distinctive virtues of blogging, which has become, I keep saying, a seasoned technology that promotes lateral thinking. When people start talking about the imminent collapse of Twitter — something that now looks like it won’t happen, and I’m inclined to bet that the next year will see a gradual return from Mastodon to Twitter — there was talk of the possibility of a blog renaissance. But I don’t think that will happen either.

You have to have a peculiar kind of mind to enjoy blogging, and even those who have such a mind might prefer platforms that enable certain modes of interaction that blogging doesn’t make easy. (For instance, speedy exchanges.) I dislike those modes of interaction, and I love to blog, so I will continue to do this.

But as Robin Sloan says in a comment I quoted the other day, “Publishing on the internet is a solved problem; finding each other on the internet, in a way that’s healthy and sustainable … that’s the piece that has never quite fallen into place.” A while back I asked a question about this: "How can I encourage readers of my blog to seek some of the benefits that I get from it?”

I do increasingly feel like that Japanese guy who paints in Excel.

An appropriate day to remember one of Waco’s greatest heroes.

Trying out the new global shortcut for microposting in MarsEdit 5 – looks like it works perfectly. Long live MarsEdit and long live blogging!

oh, okay, one more post

On these matters. This from Roald Dahl’s story “The Great Automatic Grammatizator” (1952):

“That’s exactly it, Mr Bohlen! That’s where the machine comes in. Listen a minute, sir, while I tell you some more. I’ve got it all worked out. The big magazines are carrying approximately three fiction stories in each issue. Now, take the fifteen most important magazines—the ones paying the most money. A few of them are monthlies, but most of them come out every week. All right. That makes, let us say, around forty big stories being bought each week. That’s forty thousand dollars. So with our machine—when we get it working properly—we can collar nearly the whole of this market!”

“My dear boy, you’re mad!”

“No, sir, honestly, it’s true what I say. Don’t you see that with volume alone we’ll completely overwhelm them! This machine can produce a five-thousand-word story, all typed and ready for dispatch, in thirty seconds. How can the writers compete with that? I ask you, Mr Bohlen, how?”

At that point, Adolph Knipe noticed a slight change in the man’s expression, an extra brightness in the eyes, the nostrils distending, the whole face becoming still, almost rigid. Quickly, he continued. “Nowadays, Mr Bohlen, the hand-made article hasn’t a hope. It can’t possibly compete with mass-production, especially in this country — you know that. Carpets … chairs … shoes … bricks … crockery … anything you like to mention — they’re all made by machinery now. The quality may be inferior, but that doesn’t matter. It’s the cost of production that counts. And stories — well — they’re just another product, like carpets and chairs, and no one cares how you produce them so long as you deliver the goods. We’ll sell them wholesale, Mr Bohlen! We’ll undercut every writer in the country! We’ll corner the market!”