a right bollocking

Well, this is surely Adam's best post title ever, but the post is really fascinating also. A key passage:

But let’s go back to this magic clod. What’s going on here? Pindar’s word is βῶλαξ (bōlax), a poetic form of the word βῶλος (bōlos) — a term still in use in English today, of course (though a bolus is more likely nowadays to refer to a lump of chewed food, than a lump of soil). In Homer the word ἐριβῶλαξ [Odyssey 13.235 and often in the Iliad] means ‘bountiful land’, literally ‘large-clod-place’, and in Theocritus [17:80] βῶλαξ is used to describe the abundant soils of the Nile. The connection, clearly, is with fertility. Pindar describes the magic clod as ἄφθιτον Λιβύας σπέρμα (afthiton Libyas sperma), ‘the indestructible sperm of Libya’, and the word βῶλος is etymologically linked to βολβός, ‘bulb’, which is to say: seed. This makes sense, I suppose. Egypt is dry and barren except where the Nile brings its fertile mud. Cyrene, Herodotus [4:158] tells us, has rain where the rest of Libya has none. Thira’s soil is enriched by its volcanic ash. Good for growing.

Reflecting on the myth that underlies Pindar’s poem, Adam notes that in that tale “the βῶλαξ comes from a divine source — the clod of God — and that’s what makes it so powerful, so consequential.” When I read that I was immediately certain that βῶλαξ or βῶλος had to be the word used in the Septuagint for the earth from which Adam — Adam our common progenitor, not Adam the novelist — was formed (Genesis 2:7). I fairly ran to my reference books, and … nope. My certainty was misplaced. The only place in the whole Bible where βῶλαξ is used is Job 7:5: “My flesh is clothed with worms and clods of dust; My skin is broken, and become loathsome.” The Septuagint renders the Genesis passage as χοῦν (dust) from γῆς (earth).

Oh well. I record this because one should acknowledge one’s strikeouts as well as one’s home runs.

capitaltruism

Effective altruism is an admirable movement, and I hope it spreads. But one of my chief concerns about the movement is how obsessively focused it is on financial matters. The question seems always to be “Where should I put my money?” This is not surprising, since the movement is so closely associated with wealthy engineers, and more specifically with Silicon Valley, where “scaling up” is often treated as a necessity. The EA emphasis is always on measurable goods, and on “maximizing utility,” with maximization primarily defined as “numbers of people helped.” If that’s how you orient yourself, then of course you end up with longtermism, because the future gives you the requisite scale. EA is thus the most perfect distillation yet of metaphysical capitalism.

So: Imagine a person who is both chronically ill and desperately lonely.

An EAer committed to longtermism would be on principle opposed to paying for the medical treatment of one person living now: that doesn’t scale and therefore doesn’t maximize utility. (I don’t think any effective altruist would disagree with this; the movement places a premium on eschewing sentimentality.)

The matter of loneliness is more interesting. It would probably be invisible to the EAer because nothing about loneliness or human connection is easily measurable, nor obviously addressable with money. (Not that people haven’t tried.) The ill and lonely person, if given a choice, might prefer illness within a loving community to rude good health in continued isolation; but that’s not something that the EAer can readily factor in.

But EAers need to think about this. Perhaps their monetary gifts can contribute to a future world in which disease is unknown and lifespans are dramatically extended; but what if those magnificently healthy people are miserable? What if they despise their long lives? It is certainly true that “thousands have lived without love, not one without water” — but have the loveless ones lived well?

What would EA look like if it asked not just about physical well-being but about the human need to love and be loved? For one thing, it would be less tempted by the abstractions and airy speculations of longtermism; for another, it would have to reckon with the limited power of money to address human ills. It would call into question its commitment to what Dickens, in Bleak House, called “telescopic philanthropy.” It would have to consider the possibility that the best way to ensure human flourishing in the future would be to strengthen our bonds with one another today.

This alternate-world EA might even take as its model someone I have mentioned in an earlier post, a character from that same novel, Esther Summerson. Esther is trying to avoid being recruited by Mrs. Pardiggle, a Victorian predecessor of EA perhaps, who has a “mechanical way of taking possession of people” and wants Esther to do the same.

At first I tried to excuse myself for the present on the general ground of having occupations to attend to which I must not neglect. But as this was an ineffectual protest, I then said, more particularly, that I was not sure of my qualifications. That I was inexperienced in the art of adapting my mind to minds very differently situated, and addressing them from suitable points of view. That I had not that delicate knowledge of the heart which must be essential to such a work. That I had much to learn, myself, before I could teach others, and that I could not confide in my good intentions alone. For these reasons I thought it best to be as useful as I could, and to render what kind services I could to those immediately about me, and to try to let that circle of duty gradually and naturally expand itself.

P.S. Maybe, given the clear correlation between religious commitment and happiness, even in the absence of robust physical health, the best thing the altruist who wants to be truly effective could do is support religious institutions. Making them stronger today would help them to be stronger in the future, so even the longtermist could sign on to such a project. Yay utilitarianism!

My prediction for Group B in the World Cup ⚽️:

- 🏴

- 🏴

- 🇮🇷

- 🇺🇸

I mean this. I think the USMNT is a shambles, largely because of inept coaching. I devoutly hope I’m wrong.

I would watch any NBA game called by Doris Burke (play-by play) and 89-year-old Hubie Brown (analyst). Yeah, Doris doesn’t usually do play-by-play but she’s great at it. They would make an incomparable duo. 🏀

A student just wrote to ask me about an independent study, and my reply to him called it an “indecent study.” I need to slow down when answering email.

Just had the loudest, longest episode of SpaceX thunder ever. Every window in the house rattling for several minutes. My guess: final testing of the rocket that will take Elon to Mars.

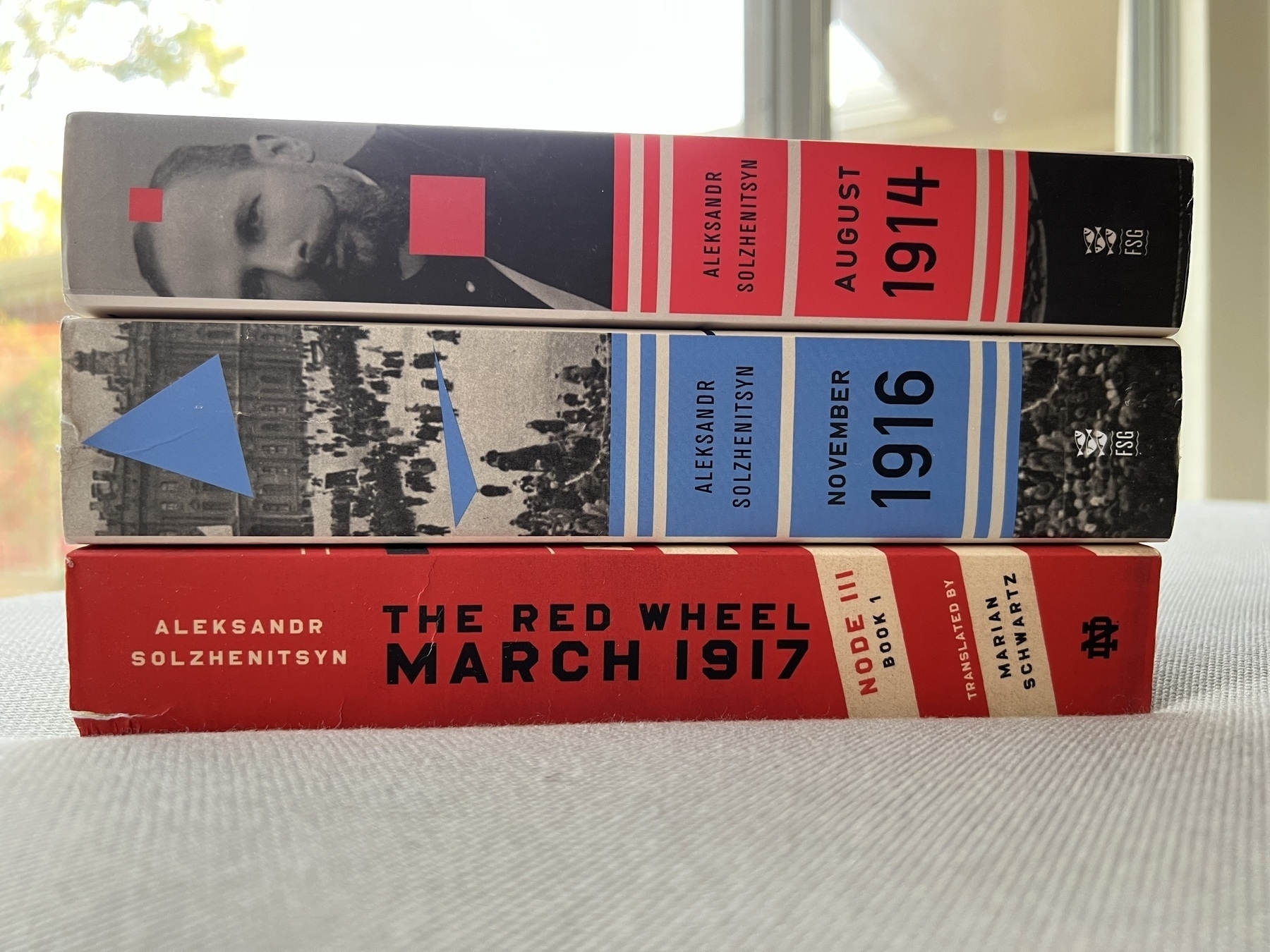

Welp, I’m going in. If you don’t hear from me in a month, call the FBI, or a priest. 📚

sprawling along the way: a polemic and an exhortation

In for a penny, in for a pounding, I always say. I really don’t want to talk about the whole “three worlds” thing again, but I’m going to, because it allows me to segue into something I do want to talk about. I just completed a book project, so I’m gonna take the time to do this stuff. Buckle up; it won’t be brief.

My friend Brad East claims that the “negative world” thesis is self-evidently true: “publicly professing to be a Christian in the 1950s was — on balance, no matter who you were or where you lived, with relatively minor exceptions — more likely than not to enhance your reputation and/or social status and/or professional-political-familial-marital-financial prospects.” In response to that I would again emphasize the distinction between the profession of faith and actual Christian living. As far as I’m concerned, a world in which the public profession of faith is rewarded but serious Christian practice is discouraged is not a positive world. It’s a Whited Sepulcher World.

I would also add that the exceptions are not “relatively minor” unless you consider the experience of Black people in America to be minor. White Americans, especially but not only in the South, have long been suspicious of what gets taught in Black churches. In her Incidents in the Live of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs narrates how the slaveholding leaders of her community demolished the church the local Blacks had built with their own hands, and then made sure they were taught by preachers whose only biblical text was “Slaves, obey your masters.” And then, of course, if you were a churchgoing Black family in my home town of Birmingham during the supposedly “positive world” era you might find that your church is bombed and your children killed. Again, this isn’t ancient history to me: the girls killed in that bombing were born less than a decade before I entered this vale of tears, which I did in a hospital about two miles from their church. I lived close enough to that church that I could have heard or felt the explosion, though I don’t remember whether I did.

So in the simplistic three-world formulation the word “world” is doing a lot of work, work it’s not capable of doing. A “positive world” for middle-class conservative white people who don’t speak out against the evils of segregation and naked hateful racism is not a positive world for Christians tout court. You can actually see Brad implicitly acknowledging that the whole debate is too vague when, at the outset of his post, he does what Aaron Renn does not do and narrows the frame of reference to the attitude of the “nation’s elite institutions” – which institutions, of course, are not our whole world.

But even if you do that, the story is more complicated than the three-worlds framework suggests. For instance, though a lunatic fringe insisted (and still insists) that Barack Obama is a secret Muslim, millions of American voters were clearly reassured by his longstanding church membership and open affirmation of the Christian faith. There’s no way he could have been elected President without being explicitly Christian – and I think it’s fair to say that the Presidency is an “elite institution.” America has never elected an avowed atheist as President, nor a Jew, nor a Muslim, and indeed the electorate taken as a whole still seems to think of some profession of Christian faith an important qualification for office. (That may well change in the future, of course.) But the kind of straightforward profession of belief in Jesus Christ that we saw in Obama, and before him in Jimmy Carter, would at any previous time in our history have been a red flag. Too much religiosity!

So there are many vectors here of varying power and varying directionality. Let me turn, then, to Derek Rishmawy’s response:

Nevertheless, it does not seem inane, politically, or pastorally irrelevant to ask the question: is there a coherent sense in which one could say the Roman world shifted to a “neutral” or “positive” stance with respect to Christian practice and confession before or after Constantine’s Edict of Milan? Is that a question that is relevant to Christian political witness and pastoral practice?I’m gonna say No. I’m gonna say that the question is indeed irrelevant, and for several reasons. First, because within the Empire conditions for Christians varied from time to time and place to place. Even at the height of Christian power there were pockets of pagan dominance; and let’s not forget that the reign of Julian the Apostate came after Constantine. Historians may be able to look back and see clear patterns, but no one at the time could have had that kind of assurance. No one knew that Constantine’s support for Christianity would succeed, or that Julian’s opposition to it would fail. Christians then had to face whatever reality confronted them in any given place, at any given moment — as do Christians today. And sometimes adherence to an abstract account of the-situation-in-general can obscure what’s right in front of your face.

I’m emphasizing how contextually variable the circumstances of Christians always are because simplistic accounts lead to strategies. The most profound problem with the three-worlds account is not that it’s wrong, though it is wrong, but that it’s supposed to yield a strategy. And let me be blunt about this: Whenever Christians decide that they need a strategy, they’re writing a recipe for disobedience to the Lord Jesus. As Stanley Hauerwas has always said in response to people who say that the Church needs a social strategy, “the Church is a social strategy.” And here’s Lesslie Newbigin:

When our Lord stretched forth His hand to heal a leper, there was no evangelistic strategy attached to the act. It was a pure outflow of the divine love into the world, and needed no further justification. Such should be the Church’s deeds of service.The Church’s job is to be the Church, and the Christian’s task is to be like Christ, and strategies invariably get in the way of both. In fact, I believe that, generally speaking, though the people who hold them typically don’t realize this, that’s just what they’re designed to do.

One of the more curious ways Christian “strategic thinking” plays out these days is in the use, by people who hold some version or another (there are several) of the negative-world hypothesis, of the example of Israel. It seems to me telling that the Catholic integralist strategy for infiltrating the corridors of power relies exclusively on Old Testment examples. Likewise this recent post by Kirsten Sanders critiquing Tim Keller’s Areopagocentric emphasis on the need for Christian persuasion:

Certainly such a view on persuasion is one way to read the biblical text. But there are other biblical accounts, too, where Israel encountered a changed world and needed to learn how to live there. Israel in Babylon wasn’t doing a whole lot of cultural exegesis or persuasion. They were learning how to pray while they longed for home.Indeed – but this neglects the essential fact that Israel were recipients of a Promise, while the Church, while inheriting that same Promise, has also been given a Commission. Jews typically don’t proselytize because they aren’t asked to. It’s always useful for Christians to look to “captive Israel” for consolation and example, but not at the expense of heeding the Commission that led Paul to Athens and the Areopagus.

Moreover, where would we Christians be if the Apostles and the holy martyrs had adopted the negative-world strategy? We would not be, is the answer. I don’t know whether there can be bitter laughter among the company of heaven, but if the martyrs know that we American Christians, beneficiaries of extraordinary legal protections for our professions of faith and inheritors of centuries of faithful stewardship, are complaining that we can’t try to persuade people because our world is too negative, then they are certainly laughing, and not in a way that would be musical to our ears.

•

So if having a strategy is wrong, what’s right? This is the part I actually want to talk about. What follows may seem personal to the point of self-centeredness, but if you bear with me I think you’ll eventually see why I take this path.A while back a friend, another Christian writer and scholar, paid me a visit and as we sipped our whisky commented, “You know, Alan, I can’t think of anyone else who has had a career remotely like yours.” And it’s true: I have had – for good or ill or (more probably) both – a very strange career. Just a few weeks ago I met with a group of Christians leaders, leaders in various fields quite different than mine, who wanted me to explain to them how I have ended up writing for the publications I write for. My response came in two parts. The first part was this: I asked them to reflect on the fact that they were the very first people ever to ask me that question. And the second part was this: The key, I said, is that I have never had a plan.

I mean, Do I really look like a guy with a plan?

A while back some Christian writers and editors stirred up an online contretemps by criticizing other Christian writers for seeking publication in “more prestigious” secular outlets. I didn’t weigh in because every online contretemps is definitionally stupid and anyway I had already made my views on this matter clear. But for those who haven’t memorized my blog history, here’s the story: I was perfectly content when I wrote my non-academic essays almost exclusively for Books and Culture and First Things, but then First Things started turning down everything I sent them and Books and Culture was shut down. I was asked to write for Christianity Today but when I suggested topics I was told that they were too academic. So when Alexis Madrigal encouraged me to write for the Technology channel of the Atlantic, and then, later, Chris Beha asked me to write for Harper’s, I did. I didn’t have a plan or a strategy – I just stopped knocking at the doors that had been slammed in my face and started going through the doors that were opened to me in welcome. Obviously there are limits to such a practice – if the Nazi Herald Tribune had asked me to write for them I would have declined – but I didn’t see anything wrong with writing for the Atlantic and Harper’s, especially they have always allowed me to make my Christianity known.

Whether I have been a good Christian witness in the public sphere I am not in a position to say. It’s very possible that I have totally wasted my opportunities, and I have often prayed that this topic not come up when I go before the Judgment Seat. But whether I have used those opportunities wisely or not, I got them precisely because I didn’t have a strategy. Instead, I had certain commitments – commitments that I wouldn’t abandon, some of which were overtly Christian and others of which were implicitly so: for instance, I wanted to write rigorously but also as elegantly as I could manage, I wanted to be deeply scholarly but also fair-minded and honest, and while non-Christians can do all those things, I am committed to them because I believe that I have been entrusted with the stewardship of certain gifts that come from God. That conviction also helps me to perceive that maybe, just maybe, if I get interested in something that doesn’t appear to be directly related to my Christian faith I may in the end discover connections I could not have anticipated. (See e.g. my persistent fascination with Daoism and anarchism.)

My conviction, for what it’s worth, is that Christians should have commitments without strategies, but instead tend to have strategies without the requisite commitments. Let me tell you what I think that leads to.

Thomas Aquinas says that hope is the virtue that lies between the two vices of presumption (praesumptio) and despair (desperatio).

Integralists, by and large, are presumptuous: they want to rule the world, but decline to ask whether they are fit to rule the world. They think being on the right side is all the justification they need. It isn’t. (Like Boromir, they cannot think of Power as anything but a gift to them.) When Thomas Merton was Master of Novices at the Abbey of Gethsemani, he would constantly remind those novices that they were in monastic life not because they were too pure for the world — which they thought they were: big stars for Team Catholic — but because they were too weak to flourish there. Christian formation begins and, I think, ends in the Jesus Prayer: Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy on me a sinner.

By contrast, those who decline to try to persuade others of the hope that is in them on the grounds that the “world” is too “negative” for that are in the grip of a kind of despair – not in relation to themselves (presumably they do not doubt that God is gracious to them) but in relation to their neighbors. To those people, I would just say that if God can speak through Balaam’s donkey He can speak through you.

Thomas says that the presumptuous and the despairing alike have something important in common, which he calls the status comprehensor – they are fixed, immobile. The despairing don’t think they can go anywhere; the presumptuous don’t think they need to go anywhere. Having a strategy pushes you towards such a stasis: by choosing in advance a particular path to follow, you are foreclosing on all the other possible paths. You are making yourself deaf to God’s unexpected calls upon your life.

What characterizes the hopeful Christian, Thomas says, is the status viator – the state of being a wayfarer. Thus Josef Pieper refers to “the wayfaring character of hope.” Wayfarers know their destination but aren’t sure how to get there; all along the way they look for signs indicating the best path, and seek help both from their companions and from those they encounter on the road. They know that they have to be flexible and agile; they know that their enemies are Aimlessness and Fixity. They trust in a Guide they cannot see; they listen for His still small voice. Maybe things will be better than they expect; maybe worse; unquestionably different. But they make their way along the pilgrim road, because they hold firm to this twofold truth about Jesus Christ: “As God, he is the goal; as man, he is the way” (Augustine, City of God XI.3).

As a wayfarer you must have a destination but you must accept the inadequacy of any strategy. You must be willing to sprawl.

Sprawl leans on things. It is loose-limbed in its mind. Reprimanded and dismissed, it listens with a grin and one boot up on the rail of possibility. It may have to leave the Earth. Being roughly Christian, it scratches the other cheek And thinks it unlikely. Though people have been shot for sprawl.

showing

You'll probably not be shocked to learn that I agree with Adam about this. My agreement is on three grounds:

First: If you want simply to tell — if you have a direct blunt message that you want to get across — there are genres for that: genres of expository and persuasive prose that have developed over the centuries for the specific purpose of communicating clear and straightforward messages. Whenever I read a didactic novel that tells me everything I am supposed to think about the story, I always think: Why did you write a novel, then? You’ve got all these “characters” and “events” getting in the way of your message. You’re not making your message better, you’re just making your story worse. Stories are best reserved for experiences and thoughts that simply won’t fit into the structure of an argument — this is, I think, what T. S. Eliot meant when he said that Henry James had “a mind so fine that no idea could violate it.” Eliot thought James distinctively attentive to those aspects of our experience that can’t be condensed into a solid idea.

Second: If you know precisely what message you want your story to convey, then your story almost certainly will never convey anything more than you explicitly intended. Which is to say, you will never learn anything more from writing it than you knew when you started. For writers who think they already know everything there is to know, this may not be a problem.

Third: If you know precisely what message you want your story to convey but are a little too artful, make it too lively, then your readers may draw conclusions you don’t want them to draw — see the experience of Bertolt Brecht as related in the final paragraph of this post. That gives you an incentive to make your story as rigid and simplistic as possible. Which means, again, you’re not making your message better, you’re just making your story worse.

Finally, I think it worth noting that this critique of show-don’t-tell appeared on Twitter, which is populated largely by people who are vigorously hunting heresies and people who are desperately trying to avoid being labeled as heretics. I can’t bring myself to read the replies to Tade Thompson’s original tweet, but from Adam’s description it seems that many of them are more hostile to “showing” than Thompson is (after all, he allows writers sometimes to show). Being on Twitter might be the worst thing writers of fiction can do, because it habituates them to the fear of Error and promotes practices of declarative belligerence. It makes them terrified of any experience that can’t be condensed into a solid idea; and that diminishes them as writers and as persons.

In a 1939 poem called “Our Bias,” Auden contrasts human beings to a lion or a rose — those creatures that simply are what they are and can’t be other:

For they, it seems, care only for success:

While we choose words according to their sound

And judge a problem by its awkwardness;And Time with us was always popular.

When have we not preferred some going round

To going straight to where we are?

Corvo

I picked up The Quest for Corvo by A. J. A. Symons secure in the knowledge that I had read it before, many years ago. Turns out I did not remember one word … so maybe I didn’t read it after all? What an extraordinary book. Just two brief notes:

First: Frederick Rolfe (AKA Baron Corvo) was a paranoid’s paranoid, and spent the final years of his impoverished life writing abusive letters to the people who had been most kind to him. Apparently he devoted much creative energy to this task: “He wrote dozens of letters, all venomous and all different, though he seldom descended to mere abuse. One began ‘Quite cretinous creature’; another ended ‘Bitterest execrations’. ‘Your faithful enemy’ was perhaps his favourite termination.”

I shall remember these rhetorical flourishes and make use of them in replying to my critics.

Second: For a time Rolfe worked for one of his most constant supporters, Ernest Hardy, then the Vice-principal of Jesus College, Oxford. He was given the unenviable task of marking examination papers, and in a letter to a friend he described the work:

This Examination (the Honour School of Literae Humaniores) is an experience. We are doing Ancient History, Logick, Roman History, Translation. The papers are perfectly appalling. The vilest, vulgarest scripts, the silliest spelling, infinitives split to the midriff. I asked Hardy what was to be done with these crimes against fair English, and he answered sedately, ‘Pass them over with silent contempt.’

That’s what I’m doing from now on when my students write poor essays or exams. Instead of explaining what went wrong and giving advice on how to do better, I shall pass over those writings with silent contempt.

There are no unsacred places;

there are only sacred places

and desecrated places.

Finished reading: The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X by Les Payne. Somewhat disappointing; the author died before the book was altogether complete, and left some organizational confusion. But the subject could scarcely be more fascinating. 📚

two essays

My Harper’s essay on (not?) becoming an anarchist is now online – though paywalled. But why not subscribe?

My (much briefer) Hedgehog Review essay “Staying for the Truth” has escaped from its paywall and become free for all to read.

I’m going to be commenting on both of these when I get some time. They’re actually quite closely related, in my mind anyway.

Currently reading: The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X by Les Payne 📚

Ronald Blythe, age 100

Rowan Williams on Ronald Blythe at 100:

“He’s somebody who is very committed to the Christian tradition and he uses it to think with, he uses it as a structure – a Christian year, the round of festivals and commemorations, for him is woven into the round of the calendar year as it would have been for generations before him,” Williams says. “You can think more freely and you may be able to feel more deeply if you’re confident that there’s this steady backdrop. You don’t have to keep making things up. There’s a world you can inhabit, your feet are on the ground, and that means you can walk around, breathe deeply and look slowly. That’s faith.”

Richard Mabey, in his introduction to the new collection of Blythe’s writings that Williams also contributes to, writes:

Ronnie's knowledge and practice of scripture are evident in many of his writings. But only in these Wormingford columns does he openly declare his quite unselfconscious, unquestioning, sometimes irreverent, and just occasionally pagan-tinged Christian faith. And as a friend but a non-believer I have to make a reckoning with this. By unspoken common consent we have never discussed religion. But at a dinner with village friends once, I betrayed my metropolitan prejudices by insisting that the church no longer had any influence on everyday social life. Ronnie turned to me and said, quietly, ‘Richard, you don't know what you are talking about.’ And as far as Wormingford is concerned he was quite correct, as these pages abundantly show. It was the closest we have ever come to a row.

a proposal

Jonathan Spence, in The Gate of Heavenly Peace, relates that the great Chinese reformer Kang Youwei, troubled by the way China in the late 19th century was dominated by other nations, founded an organization called the Know Our Humiliation Society. We American Christians need one of those.

Currently reading: Trading Twelves: The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray by Ralph Ellison 📚

rethinking work

The battle for telecommuting is a proxy for a deeper unrest. If employees lose remote work, the last highly visible, virus-prompted workplace experiment, the window for future transformation might slam shut. The tragedy of this moment, however, is how this reform movement lacks good ideas about what else to demand. Shifting more work to teleconferencing eliminates commutes and provides schedule flexibility, but, as so many office refugees learned, remote work alone doesn’t really help alleviate most of what made their jobs frantic and exhausting. We need new ideas about how to reshape work, and anthropology may have something to offer.

Newport, to his credit, acknowledges that the common tropes on this subject — “We are wired to do X because our hunter-gatherer ancestors did Z” — are simplistic at best and often misleading. But I’m still not sure his anthropological anecdotes tell us a lot that’s helpful.

What’s more important is that modern office work is dehumanizing and stress-inducing in ways that even the office work of a hundred years ago was not. (Note: that doesn’t mean that those early patterns of work didn’t have their own problems, some of them major.) I don’t think any anthropological research, or any recent writing about work, captures the differences between the the computerized workplace and earlier modes of work than Mark Helprin’s 1996 essay “The Acceleration of Tranquility” — which even now I think about regularly because it’s not just about work but also about the kinds of material conditions, the furniture of everyday life as it were, that enable flourishing.

One final note (in this post, anyway; I do want to return to the topic): What Newport is discussing here applies only to office work. There are other kinds of work — including my own, as a teacher — that are grossly diminished when done remotely, and of course many more (surgery, carpentry) that can’t be done remotely at all. But so many people in our society do office work that we really do need to be looking for ways to make it less miserable.

If Twitter does fail, either because its revenue collapses or because the massive debt that Musk’s deal imposes crushes it, the result could help accelerate social media’s decline more generally. It would also be tragic [me: tragic?] for those who have come to rely on these platforms, for news or community or conversation or mere compulsion. Such is the hypocrisy of this moment. The rush of likes and shares felt so good because the age of zero comments felt so lonely — and upscaling killed the alternatives a long time ago, besides.

If change is possible, carrying it out will be difficult, because we have adapted our lives to conform to social media’s pleasures and torments. It’s seemingly as hard to give up on social media as it was to give up smoking en masse, like Americans did in the 20th century. Quitting that habit took decades of regulatory intervention, public-relations campaigning, social shaming, and aesthetic shifts. At a cultural level, we didn’t stop smoking just because the habit was unpleasant or uncool or even because it might kill us. We did so slowly and over time, by forcing social life to suffocate the practice. That process must now begin in earnest for social media.