comparisons are odorous

Don't Fear the Artwork of the Future - The Atlantic:

What is so tiresome about the fear of AI art is that all of this has been said before—about photography. It took decades for photography to be recognized as an art form. Charles Baudelaire famously called photography the “mortal enemy” of art. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which was among the first American institutions to collect photographs, didn’t start doing so until 1924. The anxiety around the camera was nearly identical to our current fear of creative AI: Photography wasn’t art, but it was also going to replace art. It was “mere mechanism,” as one critic put it in 1865. I mean, it’s not art if you’re just pushing some buttons, right?

This is one of the laziest tropes of pseudo-thinking, but also one of the most common. If you want to try it for yourself, follow these steps:

- Note that people are afraid of something;

- Find something in history that people were unnecessarily afraid of;

- Conclude that if people were wrongly afraid of something in the past, then, logically, people who are afraid in the present must also be wrong.

Indubitable! (Just make sure you don’t notice any situations in the past in which the people who were afraid were right. Nobody says, “Those who worry about appeasing Putin should remember that in the late 1930s a bunch of nervous Nellies worried about appeasing Hitler too.”)

But often there’s another element of dumbness to this kind of take: not just the inability to reason sequentially, but the ignoring of inconvenient facts. For while photography didn’t “replace art,” it largely did replace certain kinds of art, and radically changed the cultural place of drawing and painting.

For my part, I think some of these changes were good and some were not so good. When it became clear that to most people photographs looked more “real,” more precisely representational, than paintings, painters began exploring various alternatives to straightforward representation: first Impressionism, pointillism, and later on completely non-representational painting. (Nowadays “photorealistic painting” is merely a joke or meta-artistic game, as in the works of Chuck Close.) I think these were exciting and vital developments, and I wouldn’t want to see them undone. But, that said, when I think about how Picasso could draw at the age of eleven —

— I do find myself wondering how he might have developed as an artist if he had been working in the days before photography. If much was gained when Picasso was liberated from straightforwardly representational art, we can’t know what was lost. But we lost something.

The rise of photography had a broader cultural consequence too. Before photography became commonplace, an ability to draw was almost a requirement for travelers. People needed to be able to make competent sketches of the exotic places they visited, because otherwise how would they be able to remember everything, or properly describe it to others? A world in which Ruskin had simply taken photographs in Venice rather than draw its monuments would be a diminished world.

So, did photography kill art? By no means. Did it change it radically? It certainly did. And were all those changes positive ones? Nope.

fighting the good fight

Some initial axioms:

- The U.S. has some genuine conservatives and genuine liberals, but not enough — or maybe it’s just that they’re not vocal enough;

- Our attentional commons is dominated by a perverse so-called Right and a perverse so-called Left, people with profoundly deformed sensibilities and broken moral compasses;

- These people are doing terrible damage to that commons and at least some degree of damage to our polis (they are sometimes restrained in the latter endeavor by a still-functioning legal system);

- It’s very difficult to write or speak about what these people are doing without falling into some of their own rhetorical excesses;

- Therefore those who think and write and speak seriously and responsibly about the flailings of our Imps of the Perverse do the Lord’s work (whether they believe in the Lord or not).

If you want roughly equal attention to pathologies across the political spectrum, then I don’t think you can do much better than Andrew Sullivan. And while I am not in general a podcast guy, Andrew turns out to be a wonderful interviewer, and his conversations with his guests often take delightfully unexpected turns.

Regular readers here will know that I have long been concerned by Christians who are willing to sacrifice obedience to Jesus if it will get them political power and/or cultural influence. Well, their gentle and equable scourge is David French, whose work you can find many places, but especially here and here.

There’s an extremely vocal school of trans activism that has come to control much our our media and a large part of the academy as well. To put it bluntly, in these matters we are regularly being lied to by our media, and a troublingly large number of scientists appear quite willing to cook their books in order to satisfy the demands of this movement. Jesse Singal does yeoman work digging into the details of this pervasive mendacity and putting hard questions to the perpetrators — but he does it in a consistently measured way and is always forthright in admitting when he gets something wrong. If you’re a podcast person, then you may well enjoy Blocked and Reported, the podcast he does with Katie Herzog, AKA “the last lesbian.”

By the way, the special report on sexuality and gender produced by The New Atlantis six years ago (!) is still very helpful. And of course, as a long-time contributor, I love that journal. A new issue came in the mail today and I leaped into it.

On the problems that arise when academics don’t care about what’s true any more, but only about what serves their political ends — and their careers — a couple of people are key, and they’re both named Jonathan. The first is Jonathan Haidt, who is prolific and sometimes seems omnipresent; I’d start with the essays listed here. The other is Jonathan Rauch, whose work is more scattered but just as valuable. His book The Constitution of Knowledge is essential, but you might want to begin with this recent essay on politicized science.

If Katie Herzog is the Last Lesbian, Freddie deBoer may be the Last Socialist.

Finally, here are a few newsletters on (broadly speaking) political topics that I find consistently useful — and useful because they’re not shilling for anyone or anything, a rare virtue these days:

- John McWhorter

- Yair Rosenberg

- Zeynep Tufecki

- Damon Linker

- Noah Millman

- Leah Libresco Sargeant (though Leah is more culture-oriented, like me)

I’m grateful to these writers because they do the hard work that makes it possible for me to focus on arts and culture. I care about the things they care about, but I don’t have their very particular set of skills, and the skills (the knowledge, the sensibilities) I do have are best employed in other venues.

P.S. Sometime I’ll do a list of arts/culture/technology blogs and newsletters that I like. Or maybe I’ll go totally retro and make a blogroll!

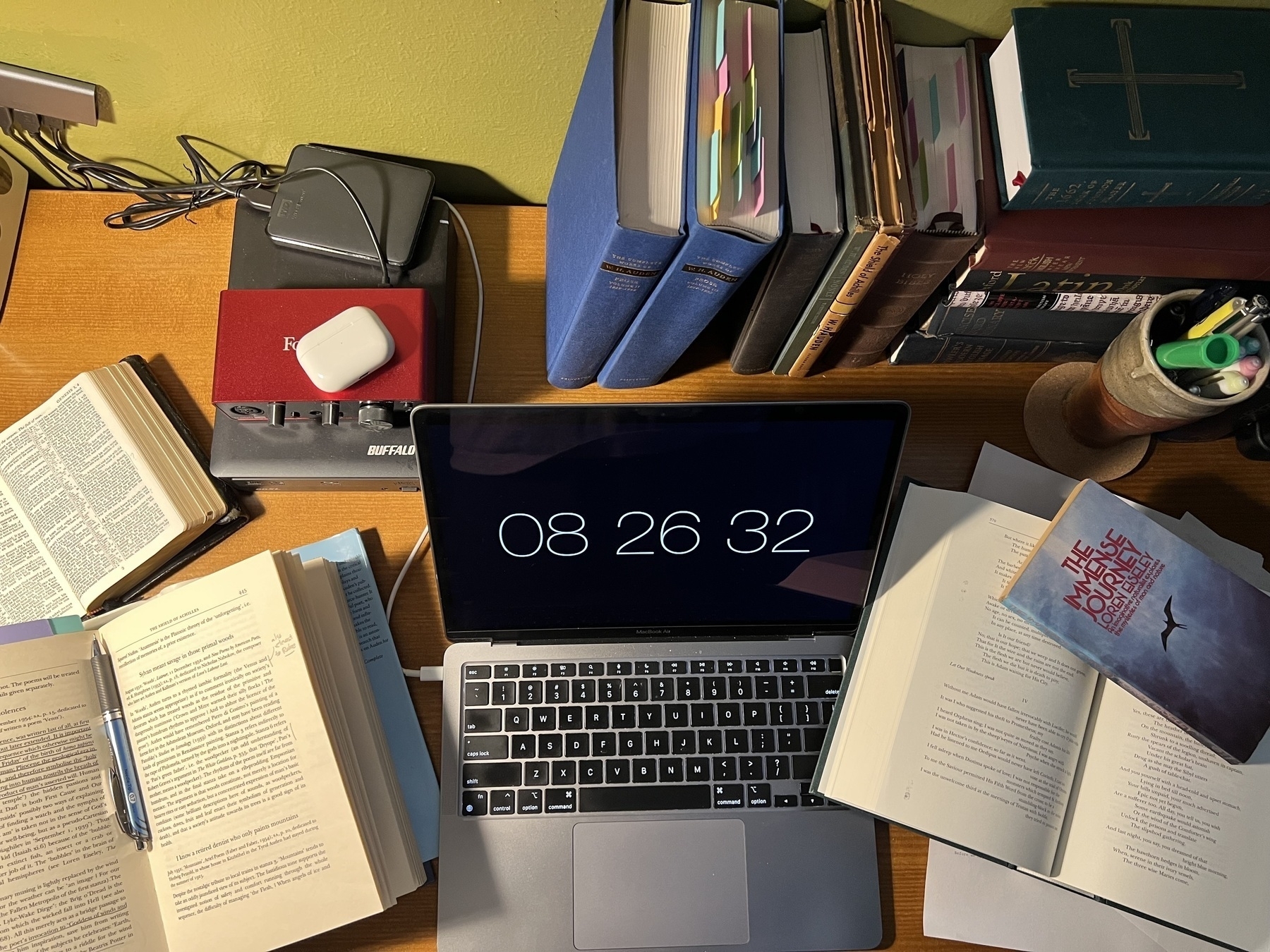

The workshop.

the arts our country requires

In a famous letter, John Adams wrote from Paris to his beloved Abigail:

To take a Walk in the Gardens of the Palace of the Tuilleries, and describe the Statues there, all in marble, in which the ancient Divinities and Heroes are represented with exquisite Art, would be a very pleasant Amusement, and instructive Entertainment, improving in History, Mythology, Poetry, as well as in Statuary. Another Walk in the Gardens of Versailles, would be usefull and agreable. But to observe these Objects with Taste and describe them so as to be understood, would require more time and thought than I can possibly Spare. It is not indeed the fine Arts, which our Country requires. The Usefull, the mechanic Arts, are those which We have occasion for in a young Country, as yet simple and not far advanced in Luxury, altho perhaps much too far for her Age and Character.Only the last two sentences of the letter are typically quoted, but I think it’s useful to see the larger context, especially Adams’s regret at the matters of great interest to him that he doesn’t fully understand and simply cannot take the time to understand. He had recently been engaged in complicated and tense negotiations with the French foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes, which around this time resulted in the Frenchman declaring that he wouldn’t deal with Adams any more but only with the less astringent Benjamin Franklin. (Perhaps Adams should have been working harder at the study of the Art of Negotiation.)I could fill Volumes with Descriptions of Temples and Palaces, Paintings, Sculptures, Tapestry, Porcelaine, &c. &c. &c. — if I could have time. But I could not do this without neglecting my duty. The Science of Government it is my Duty to study, more than all other Studies & Sciences: the Art of Legislation and Administration and Negotiation, ought to take Place, indeed to exclude in a manner all other Arts. I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Painting and Poetry Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.

It’s interesting to note the change of mind he undergoes between the penultimate and final sentence: in the former he thinks his sons may well study Painting and Poetry, but then he reconsiders and thinks, well, perhaps it would be better for them to pursue “Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture” and the like so that their sons can study Painting and Poetry. His was, after all, “a young Country, as yet simple and not far advanced in Luxury” — and not likely to be much further advanced in a single generation.

Well, right now we seem to be regressing towards Adams’s state of affairs. Everyone in power, or aspiring to power, in this country seems to be studying Politics and War, though they will sometimes cover that study with a flimsy disguise.

On the so-called Left we see surveillance moralism (and often enough the sexualization of children and early teens) masquerading as science.

On the so-called Right? It’s wrathful trolling masquerading as political philosophy.

None of these folks, God bless their earnest if shriveled hearts, have any room inside for the arts. Everything has to serve their political purposes, and works of art are rarely sufficiently blunt instruments. Thus Michael Lind writes — in an otherwise useful essay — that the goal of the public intellectual is to “influence voters,” because what other reason could an intellectual possibly have for writing? (Michael Lind is a very intelligent and often illuminating writer, but he really does seem to think that nothing exists in the human world except electoral politics.) The one arguably-artistic preference these would-be elites of Left and Right share is a liking for Game of Thrones (and now House of the Dragon) but only because that world is a wish-fulfillment dream for aspiring tyrants.

Well, here at the Homebound Symphony I’ll be focusing on the arts more and more, and if sometimes connecting their wisdom to the social and political concerns that trouble our minds and dreams, I’ll try never to do it in a way that blunts those sharp instruments that pierce soul and spirit. And I’ll do this in honor of John Adams, so that his sacrifice was not in vain.

(I also think there are every good reasons for Christians to be especially attentive to the arts — even those Christians who don’t think of themselves as arty. That may be a topic for future posts, because my reasons for so thinking are not common ones.)

But I can do all this because of others who are doing some necessary but ugly work. The internet’s own John Adamses … sort of. I’ll write a follow-up post on some of these helpful people.

“The Godfather is shit. But there is a part of me that loves shit.” — Jean-Luc Godard

defeaters

Ukraine Can Win This War - by Liam Collins and John Spencer: Two or three times a day I see an article like this one: a confident prediction that Ukraine is in a winning position that never once considers the possibility that Russia will use nukes. I don’t see how this is anything other than the purest wishful thinking. The Ukrainian politician who says that Russia is like a monkey with a hand grenade is reckoning more seriously with the real conditions of this war.

Here’s my thesis about our current political discourse: The more controversial the topic, the more likely that writers on it will simply ignore any perspective other than their own. They won’t consider it even to refute it; they’ll just pretend it doesn’t exist.

My secondary thesis is that such people try really hard not to think of alternatives because they know they can’t deal with the objections. A. E. Housman used to say that many textual critics simply ignore possibilities for establishing a reading of a text other than the one they prefer because they’re like a donkey poised equidistant between two bales of hay who thinks that if one of the bales of hay disappears he will cease to be a donkey.

Epistemologists like to talk about defeaters of a particular proposition: it’s SOP, for them, when making an argument to ask: What eventuality would defeat my proposition? People writing enthusiastically that Ukraine will win this war never ask that question because the answer is both obvious and terrifying: Ukraine won’t win this war if Russia uses nuclear weapons against them.

monarchy

Having written recently about the death of Queen Elizabeth, I’d like to call attention to some of the things I’ve written in the past about what I believe to be the essentially monarchical character of the human imagination:

- My essay for the Cambridge Companion to C. S. Lewis on the Narnia books, which I argue have a single theme: disputed sovereignty

- A post on the very idea of the return of the King

- An essay on how Emile Durkheim’s portrayal of the dominant concerns of traditional or “primitive” societies has a modern afterlife

- An essay on the ongoing power of what Leszek Kołakowski calls “mythical thinking” (and do check out the Kołakowski tag at the bottom of this post)

Short version of all this: Every distinction we make between our “modern” selves and our “primitive” ancestors is wrong. We’re exactly like them in all the ways that really matter for our own self-understanding.

Made pesto today in this food processor, which is forty years old. I know old people like to say “They don’t make ‘em like that any more, but sometimes it’s true. If we ever have gandchildren, we’ll probably pass this along to them.

“There are no dull subjects, only dull minds.” — Raymond Chandler, “The Simple Art of Murder”

The world has no real plan to stop the genocide underway in China. Some Uyghurs are at the point where they wish the world would just cop to that harsh fact, rather than paying lip service and raising their hopes over and over.

“We had an illusion that the world would do its best to stop China from this genocide,” said Tahir Imin, a US-based Uyghur academic who believes many of his relatives are in the camps. “But the world has no plan to stop this genocide. It’s not happening. The governments should clearly say that. Either stop the genocide — or admit you will not.”

Have been trying got the past couple of years to avoid buying anything made in China, because much of it is made by slave labor — but it seems that everything I might want to buy is made there. So I just have to redouble my efforts.

I keep thinking about what the late great Paul Farmer said: “I love WL’s [White Liberals], love ’em to death. They’re on our side. But WL’s think all the world’s problems can be fixed without any cost to themselves. We don’t believe that. There’s a lot to be said for sacrifice, remorse, even pity. It’s what separates us from roaches.”

name change

I decided to change the name of this blog, for reasons that should be clear from recent and future posts. But ICYMI, the namesake post of the blog is here.

The newsletter will continue to be called Snakes & Ladders. I like the idea of the two endeavors having different names.

two versions of covid skepticism

From a long, intricate, subtle, and necessary essay by Ari Schulman:

The skeptical type I have targeted here is not the one who believes merely that prolonged school closures were a travesty (which is true), that natural immunity should have counted as equivalent to vaccination (true), that an egalitarian view of the virus meant that too little was done to protect people in nursing homes (true), that with different choices, restrictions could have ended far sooner than they did (true again).

No, he was the one who gave himself over wholly to Unmasking the Machine. Starting from entirely reasonable frustrations, the skeptical project took its followers to dark places. The unmasker insisted a million of his countrymen would not die and then when they did felt no reckoning. He at one moment cast himself as Churchill waiting to lead us out of our cowering fear of the Blitz (Death is a part of life) and in the next said that actually the Luftwaffe is a hoax (Those death certificates are fake anyway). He feels no reckoning because he has been taken in by a force as totalizing as the Technium’s; he is so given over to it that he too no longer accepts his own agency.

This skeptic is no aberration. An entire intellectual ecosystem is fueled by his takes. He owns, if not the whole movement of the Right, then certainly its vanguard.

Yet still, still one can hear the reply: Corrupt powers lied and demanded ritual pieties and put their boot on our necks and tore the country apart, and you want a reckoning from us?

An understandable reply — but the answer is, Yeah, we’d like a reckoning from you skeptics, because in a well-functioning society people don’t demand accountability and responsibility only from their political opponents.

At the heart of Ari’s essay is a simple yet essential distinction between two phenomena: (a) skepticism about the competence and integrity of our technocratic public health regime and (b) skepticism about the seriousness of the coronavirus. Those who were right about the former all too often allowed themselves to be drawn into the latter. And very few of those who were most dismissive of the dangers posed by Covid have admitted their error — they’re too busy taking a “victory lap” because they think — with, as Ari shows, a good deal of justification — that they were right about the self-serving turf-protecting rigidity of the regime.

(And if you don’t think National Review can be trusted with regard to the profound shortcomings of that regime, then by all means read Katherine Eban’s many illuminating and distressing reports in Vanity Fair.)

As I look back on my own scattered writings on this topic, I think I often made the opposite error: because I rightly took seriously the dangers of the coronavirus, I was often too trusting of the regime.

secret ambivalence

In an earlier post I talked about how good Pauline Kael’s early film criticism — her pre-New Yorker writing — is, and another fine example comes from a long essay she wrote in 1964 for Film Quarterly about Hud. Well, about Hud, yes, but even more about the critical response to Hud.

For instance, she noted this take by Bosley Crowther in The New York Times:

The human elements are simply Hud, the focal character, with his aging father, a firm and high-principled cattleman, on one hand, and Hud's 17-year-old nephew, a still-growing and impressionable boy, on the other. The conflict is simply a matter of determining which older man will inspire the boy. Will it be the grandfather with his fine traditions or the uncle with his crudities and greed? It would not be proper to tell which influence prevails. Nor is that answer essential to the clarification of this film. The striking, important thing about it is the clarity with which it unreels.

The moral clarity is key to Crowther, and to several other reviewers quoted by Kael. What they like is how unambiguously the movie affirms the archaic moral standards upheld by Hud’s father Homer, and consequently rejects Hud’s selfishness and immaturity.

Dwight Macdonald, writing in Esquire, hated the film for the very reasons that the much larger crowd represented by Crowther loved it:

The giveaway is Hud’s father, the stern patriarch who loves The Good Earth, the stiff-necked anachronism in a degenerate age of pleasure-seeking, corner-cutting, greed for money, etc. — in short, these present United States. How often has Hollywood (where these traits are perhaps even more pronounced than in the rest of the nation) preached this sermon, which combines maximum moral fervor with minimum practical damage; no one really wants to return to the soil and give up all those Caddies, TV sets and smart angles, so we can all agree to his vague jeremiad with a pious, “True, true, what a pity!” In Mr. Ritt’s morality play, it is poor Hud who is forced by the script to openly practice the actual as against the mythical American Way of Life and it is he who must bear all our shame and guilt.

Kael’s view — and does she ever delight in proclaiming it — is that everyone is wrong. They’re wrong because Hud is “one of the few entertaining American movies released in 1963 and just possibly the most completely schizoid movie produced anywhere anytime.” Indeed, it is entertaining because it’s schizoid. It is internally divided because it both hates Hud and loves him, repudiates him and affirms him; and the audience shares in this complex of emotions, because the audience is America, and this tension between the upholding of “traditional values” and the relentless pursuit of self-gratification is maybe the single most essential element of the American character.

I think this reading is compelling. But I also want to set it … not against, but rather alongside a slightly different one: If the audience loves and affirms Hud, might that be not so much because it identifies with Hud’s selfishness but rather because Hud is played by Paul Newman? Men-want-to-be-him-and-women-want-to-be-with-him Paul Newman? There is something about the charisma of a real movie star that shapes our responses in ways that we can’t altogether control.

I wonder if Kael doesn’t fall for this charisma, to some extent. Now, to be sure, Kael believed in the sexual liberation of women long before it was cool to do so, and we were in 1964 on the cusp of a culture-wide sexual revolution; but even so, it’s strange to hear her question whether Hud’s attempt to force Alma to have sex with him should really be called “rape.” Kael’s logic is that Alma is sexually attracted to Hud and is only resisting him because she wants an “emotional commitment,” so if he forced himself on her he would be giving her something she actually wants — ergo, not rape. (So No means Yes, here as in the minds of thousands of frat boys who think that if any woman is drunk that makes them Paul Newman.) I wonder if Kael would have made this particular argument if Hud had been played by a less gorgeous actor.

Whether or not the movie has the universal clarity that Crowther attributes to it, it seems pretty clear about this business. In his last conversation with Alma, Hud calls his attempt to rape her a “little ruckus,” and declares, “I don't usually get rough with my women. I generally don't have to.” Well, we learned what he does when he thinks he has to, didn’t we?

But charisma and beauty may not be the only forces at work in shaping our response to someone like Hud — there’s also the simple power of putting someone at the center of our attention, especially if that person can act well. Think of how Breaking Bad did everything it could possibly do to reveal Walter White’s transformation into an utter monster, yet, nevertheless, #TeamWalt was a huge thing on social media. And not because Bryan Cranston was presented to us as sexually alluring.

Another example: when Bertolt Brecht wrote Mother Courage and her Children, a play about a camp follower in the Thirty Years War who through her limitless greed endangers and ultimately destroys her children, he was shocked by the response of the first audiences of the play. Mother Courage is a kind of exemplar of capitalism, and her story is meant to demonstrate the ways that capitalism feeds on war. But of course capitalism doesn’t consciously and intentionally set out to destroy human beings; Brecht was too honest an artist to suggest that, so he certainly wasn’t going to make Mother Courage a slavering child-murderer. She is shocked and genuinely grieved when her children die, and doesn’t realize her complicity in their deaths. So when Therese Giehse, in playing the part of Mother Courage, cried out in her grief at the death of her sons, the audience was so moved that all they felt at the end of the play was was pity for the poor woman who had been deprived of her children. This both surprised and infuriated Brecht, who thought that it was perfectly apparent that her insatiable greed and consequent thoughtlessness towards everything else had led to the children’s deaths, so he rewrote the play to make an already obvious message even more obvious. Unmistakable, unmissable. And when the audience saw this new version of the play, they thought: Poor woman, her children are dead!

Donald Trump says that as President he could declassify documents just by “thinking about it.” NOT TRUE. He also needed to do this:

Today’s American evangelical Christianity seems to be more focused on hunting heretics internally than perhaps in any other generation. The difference, however, is that excommunications are happening not over theological views but over partisan politics or the latest social media debates.

I’ve always found it a bit disconcerting to see fellow evangelicals embrace Christian leaders who teach heretical views of the Trinity or embrace the prosperity gospel but seek exile for those who don’t vote the same way or fail to feign outrage over clickbait controversies.

But something more seems to be going on here — something involving an overall stealth secularization of conservative evangelicalism. What worries me isn’t so much that evangelical Christians can’t articulate Christian orthodoxy in a survey. It’s that, to many of them, Christian orthodoxy seems boring and irrelevant compared to claiming religious status for already-existing political, cultural, or ethnonational tribes.

A strong and sad Amen to this. It is perfectly clear that there is a movement in America of people who call themselves evangelicals but have no properly theological commitments at all. But what’s not clear, to me anyway, is how many of them there are. Donald Trump can draw some big crowds, and those crowds often have a quasi-religious focus on him or anyway on what they believe he stands for — but those crowds are not large in the context of the entire American population. They’re very visible, because both Left and Right have reasons for wanting them to be visible, but how demographically significant are they really?

I have similar questions about, for instance, the “national conservatism” movement. Is this actually a movement? Or is it just a few guys who follow one another on Twitter and subscribe to one another’s Substacks?

Questions to be pursued at the School for Scale, if I can get it started.

an allegory of American political life, especially online

Dante, Inferno, Canto XXX (Hollander translation):

And I to him: ‘Who are these two wretches

who steam as wet hands do in winter

and lie so very near you on your right?’‘I found them when I rained into this trough,’

he said, ‘and even then they did not move about,

nor do I think they will for all eternity.‘One is the woman who lied accusing Joseph,

the other is false Sinon, the lying Greek from Troy.

Putrid fever makes them reek with such a stench.’And one of them, who took offense, perhaps

at being named so vilely, hit him

with a fist right on his rigid paunch.It boomed out like a drum. Then Master Adam,

whose arm seemed just as sturdy,

used it, striking Sinon in the face,saying: ‘Although I cannot move about

because my legs are heavy,

my arm is loose enough for such a task.’To which the other answered: ‘When they put you

to the fire, your arm was not so nimble,

though it was quick enough when you were coining.’And the dropsied one: ‘Well, that is true,

but you were hardly such a truthful witness

when you were asked to tell the truth at Troy.’‘If I spoke falsely, you falsified the coin,’

said Sinon, ‘and I am here for one offense alone,

but you for more than any other devil!’‘You perjurer, keep the horse in mind,’

replied the sinner with the swollen paunch,

‘and may it pain you that the whole world knows.’‘And may you suffer from the thirst,’ the Greek replied,

‘that cracks your tongue, and from the fetid humor

that turns your belly to a hedge before your eyes!’Then the forger: ‘And so, as usual,

your mouth gapes open from your fever.

If I am thirsty, and swollen by this humor,‘you have your hot spells and your aching head.

For you to lick the mirror of Narcissus

would not take much by way of invitation.’I was all intent in listening to them,

when the master said: ‘Go right on looking

and it is I who’ll quarrel with you.’ [...]‘Do not forget I’m always at your side

should it fall out again that fortune take you

where people are in wrangles such as this.

For the wish to hear such things is base.’

Ché voler ciò udire è bassa voglia — to will to listen to such contemptible trash, to desire it, is base, low, self-degrading. Let me be Virgil to your Dante: When people online or on TV are going at each other, when they’re engaged in their spittle-flecked mutual recriminations — avoid it, flee it. Find something, almost anything, else to do with your time.

forking paths

Deepfake audio has a tell and researchers can spot it — yes, there’s a tell now, but will there always be? Deepfake audio, deepfake video, DALL-E image generation — all of this will be getting better and better, and it’s difficult to imagine that tools to identify and expose fakes will keep up, much less stay ahead.

I think we’re looking at not one but two futures — a fork in the road for humans in Technopoly. (In many parts of the world it will be a long time before people are faced by this choice.)

A few will get frustrated by the fakery, minimize their time on the internet, and move back towards the real. They’ll be buying codex books, learning to throw pots or grow flowers, and meeting one another in person.

The greater number will gradually be absorbed into some kind of Metaverse in which they really see Joe Biden transformed into Dark Brandon or hear Q whisper sweet nothings into their ears. In the movies the Matrix arises when machines wage war on humans, but I think what we’ll be seeing is something rather different: war won’t be necessary because people will readily volunteer to participate in a fictional but consoling virtual world.

I know which group will have more freedom, and more flourishing; but I wonder which will have more power? Not everyone who stays in the real world will do so for decency’s sake.