Currently reading: Their Finest Hour (The Second World War) by Winston S. Churchill 📚

I continue to be interested in how the iPhone software handles low light, especially when using the longest lens. Here’s another example taken at night.

Blimp

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) is an odd movie, because it’s essentially an argument for something it never directly mentions: the bombing of German cities.

It’s divided into three periods: the Boer War, the Great War, and World War II. In each of them our protagonist, Clive Wynne-Candy, is a soldier: first a Lieutenant, then a General, then a retired General working with the Home Guard. In each period his actions are governed by a strong sense of fair play and gentlemanly dignity. The point of the movie, as I see it, is to honor him for that lifelong integrity but to insist that the time for such integrity is over.

The keynote is struck when Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff, his old friend and one-tome romantic rival, a German driven from his country by his opposition to Nazism, says: “Dear old Clive, this is not a gentleman's war. This time you're fighting for your very existence against the most devilish idea ever created by a human brain: Nazism. And if you lose, there won't be a return match next year; perhaps not even for a hundred years.” Wynne-Candy is repeatedly described as someone for whom war is a game, if a solemn game, and who therefore prides himself on playing by the rules. But when one is faced by an enemy such as the Nazis — an enemy that knows no rules, no laws, no principles — one must throw out the book.

This is the argument also of a young soldier whose mockery of Wynne-Candy sets the movie’s story in motion, and Wynne-Candy ultimately accepts the mockery. He knows, and says, that he cannot change, but he also comes to believe that he must pass the torch to those who are willing and able to fight the Nazis in the same way the Nazis fight. He pledges to take that soldier to dinner, and in the movie’s last scene he salutes him. (Note that Wynne-Candy is not dead: it is all that he has stood for, the Colonel Blimp in him and in England, that has died. But Colonel Blimp here stands not for the blustery jingiosm of the comic but rather for a set of moral standards applied equally in peace and in war.)

We are clearly meant to admire him for his sense of honor, but even more for his awareness of his own superannuation. And then what remains is to do to the cities of Germany what the Nazis have done to London and Coventry. Maybe that position is right and maybe it’s wrong, but there’s no doubt that it’s the position The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was produced in order to defend.

(It’s noteworthy that Churchill hated the movie, even though it supports the war policy that he himself advocated and carried out. Apparently Churchill didn’t like the idea of a wartime movie with a sympathetic German character, even if the character is fervently anti-Nazi and is played by an Austrian Jew who came to Britain in 1936 to escape Nazism.)

My friend Tim Larsen with an interesting thought:

In all of human history Queen Elizabeth II is the single person who has been most prayed for. From her birth in 1926 she was included in a petition myriads of people prayed day after day: It called upon the Almighty to bless and preserve “all the Royal Family.” From her accession to the throne in 1952, millions began to pray for her daily by name: “That it might please thee to keep and strengthen ... thy Servant Elizabeth, our most gracious Queen and Governor.” A modern form introduced during her reign that is often used today pleads, “Guard and strengthen your servant Elizabeth our Queen.”

For a healthy balance between the apophatic and kataphatic we should look to the liturgy. The liturgy is a complex performance, a ritualized midrash on Holy Scripture that alternates between moments of knowing and not-knowing. Think of the Sanctus, where the seraphic hymn of “holy, holy, holy” declares the LORD’s radical otherness even as it announces his presence among us. The readings and their commentary in the sermon would seem to represent a powerfully kataphatic moment, and so they are; we do not proclaim the gospel with our fingers crossed. And yet the public reading of Scripture, a practice especially dear to Anglicans, reminds us that there is always more of Scripture than we can exhaust with our ideas about it. Sadly, the lectionary regularly edits out some of the weirder stuff in the Bible. We could use more of the weird stuff — more reminders that God is God, and that there is always more of God to know. Yet at the heart of the entire liturgy stands the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus, in whom the invisible God has made himself startlingly well-known to us humans. The passion is a divine mystery that in a certain way excludes us; it is God who is the agent here, not ourselves. And yet the assembly that celebrates it is the body of Christ, the community of those who have been incorporated into Christ’s passion and death, and in him offer their worship to the Father.

introducing

Six Books With Introductions Worth Pausing Over: Well, okay. Since I have tried to be a conduit for old books, I have no business criticizing this — but hey, like Iago I’m nothing if not critical, so:

The six “stories from the past” were published in: 1916, 1980, 1869, 1952, 1983, and, basically, 1906-08 (the period during which Henry James dictated to a secretary his prefaces to his novels). Might it not be possible to have a more expansive sense of “the past”?

So here are a few essays that reckon with the ongoing value and power — the power to speak to us, to our condition — of genuinely old texts:

- Simone Weil, “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force”

- Bernard Knox, “The Oldest Dead White European Males”

- Daniel Meldelsohn, “Lost Classics” and this essay on the Aeneid and empire

- Brian Phillips (yes, the soccer guy): “The Tale of Genji as a Modern Novel” (very much worth getting through the JSTOR paywall if you can)

For deeper dives — from recent writers and not-so-recent ones — see Mendelsohn’s An Odyssey: A Father, A Son, and an Epic, Erich Auerbach’s Dante, Poet of the Secular World, Edward Mendelson’s The Things That Matter, and M. I. Finley’s The World of Odysseus.

These are all texts that wrestle, sometimes uncomfortably, with stories from the past, stories that always speak to us but sometimes in strange dialects.

On, and please read Auden’s great poem “The Shield of Achilles.”

Currently reading: The Gathering Storm (The Second World War) by Winston S. Churchill 📚

Had the Queen died earlier in the year, it’s not difficult to imagine Johnson harnessing the event to his great survival project. So we should be grateful she lived long enough to save us the prospect of Johnson in Westminster Abbey, mugging his way through Ecclesiastes and hinting that, in a way, she had been the Boris of people’s hearts. Think of it as her final service to the nation.

This is a very good point.

The rain did a lot for this fella.

What the iPhone software does with very low light (don’t be deceived by the sky in the background, this was taken in a pitch-black night) sometimes looks like rotoscope animation.

Maya Jasanoff's idea that “The new king now has an opportunity to make a real historical impact by scaling back royal pomp and updating Britain’s monarchy to be more like those of Scandinavia” — because Colonialism! — is (a) the platonic ideal of an NYT opinion piece and (b) a perfect illustration of Clement Atlee’s comment that "the intelligentsia … can be trusted to take the wrong view on any subject.” The pomp of the British monarchy is the point; the ceremony is the substance — for good reasons and bad. When the ceremony is discarded the monarchy will be too. And rightly so.

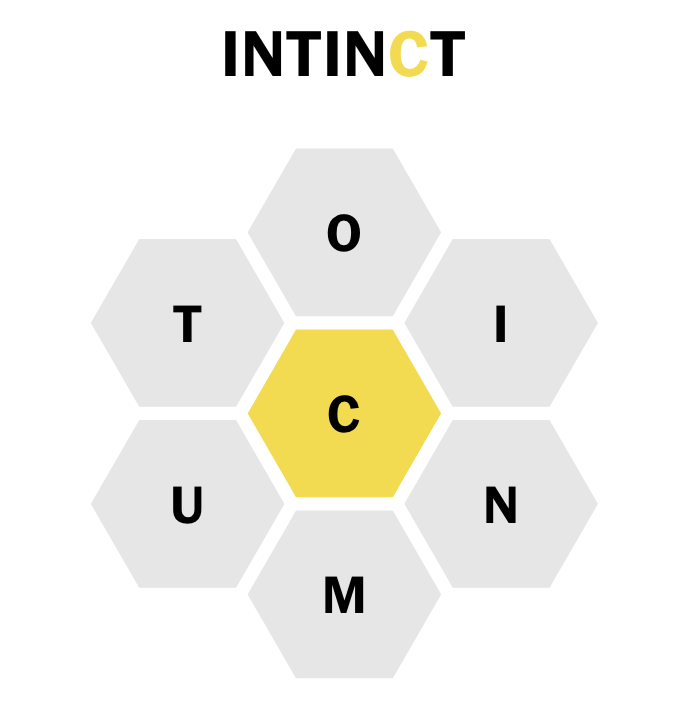

I told them a while back that this is a word, but they obviously didn’t listen. Anti-liturgical bias at the NYT!

Currently reading: The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn 📚

Elizabeth II: a constant queen whose failings were rare: “She possessed, apparently, the unique skill of being able to position a tiara on her head perfectly without a mirror.” No, not unique — I too have this skill, though I have had fewer opportunities to exercise it than the late Queen did. Sad.

God Save the Queen

It is a truth universally acknowledged that if we do not suffer from our ancestors’ sins, then we have no need of their virtues. This truth has about as much validity as the one I’m riffing on, but it is if anything more firmly believed. To our great loss.

The late Queen Elizabeth II played the hand she was dealt about as well as it could possibly have been played, and this required her to exercise virtues that few of our public figures today even know exist: dutifulness; reliability; silence; dignity; fidelity; devotion to God, family, and nation. We shall not look upon her like again; her death marks the end of a certain world. Its excellences, as well as its shortcomings, are worthy of our remembrance.

This may perhaps be a good time to listen to the small but sumptuous motet that Ralph Vaughan Williams composed for the Queen’s coronation:

I know this kind of thing is totally normal now — one of the most characteristic ways for journalists to use Twitter — but let’s be clear what it’s saying: I already know what the thesis of my story will be, so please write if you can confirm my thesis. He doesn’t want to hear from anyone who might offer an alternative account to the one he has already settled on.

The Woman Who Became a Company:

Since corporations can claim trade secrets, [Jennifer Lyn] Morone decided to resist pervasive data capture by incorporating herself, so that the company, JLM Inc., contains the intellectual property and activities of the human Morone. If a corporation can be a person, perhaps a person could be a corporation and so protect their data! The articles of incorporation enable Morone’s data to qualify as intellectual property and thus purport to offer protections from the data marketplace. The human Morone’s privacy is possible because it is the product and trade secret of the company, JLM Inc., which is incorporated in the state of Delaware. With its own Court of Chancery that hears cases involving corporate law, Delaware’s legal structure is favorable to business. The state also does not collect corporate taxes from those that do business outside the state or tax “intangible assets” — like data. […]

As JLM Inc., Morone has an obligation to refuse the terms and agreements that permit apps and websites to share data with their parent tech companies, alongside third and fourth parties. She must protect the secret formula of who she is so that she can sell it, making it a challenge for her to participate in many of the interactive information streams common to the 21st century. She can’t use apps, websites with cookies, or most search engines. They track her and collect data about her. That data is the property of JLM Inc. and so she must not engage these services. The problem with maintaining the marketplace as the point of reference for data governance is how it reinforces exploitative practices that don’t have clear, long-term safeguards for participants. Morone’s experience shows that the corporation doesn’t provide a solution to the extractive practices of these apps, platforms, and sites for a human who wants to live, work, or socialize today.

Everything about this story is deeply sad.

creating the Vernacular Republic

Ivan Illich, from In the Mirror of the Past:

Rather than life in a shadow economy, I propose, on top of the z-axis, the idea of vernacular work: unpaid activities which provide and improve livelihood, but which are totally refractory to any analysis utilizing concepts developed in formal economics. I apply the term ‘vernacular’ to these activities, since there is no other current concept that allows me to make the same distinction within the domain covered by such terms as ‘informal sector, ‘use value,’ ‘social reproduction.’ Vernacular is a Latin term that we use in English only for the language that we have acquired without paid teachers. In Rome, it was used from 500 B.C. to 600 A.D. to designate any value that was homebred, homemade, derived from the commons, and that a person could protect and defend though he neither bought nor sold it in the market. I suggest that we restore this simple term, vernacular, to oppose commodities and their shadow. It allows me to distinguish between the expansion of the shadow economy and its inverse the expansion of the vernacular domain.

One of Les Murray’s collections of poems is called The Vernacular Republic, and while that title is usually thought to refer to Australia simpliciter, I don’t think that’s right. The Vernacular Republic is more an ideal image of Australia, what it might have been and perhaps (with repentance) still could be.

I think if we take Illich’s understanding of the vernacular domain, and add to it the image of an alternative but “more comprehensive” economy that Wendell Berry writes of, then we have a rough outline of what a genuine Vernacular Republic would be. The Vernacular Republic is an “informal sector” that opposes the logic of commodity and gradually but steadily practices the Kingdom of God.