a friendly reminder

A year ago I wrote: “Wondering how to decide what to read? Here’s a simple but effective heuristic to cut down the choices significantly. Ask yourself one question: Does this writer make bank when we hate one another? And if the answer is yes, don’t read that writer.” The same rule applies to TV, radio, podcasts. If their clicks and ratings and ad revenues go up when we hate one another, flee them like the plague they are.

Big the-Virgin-and-the-Dynamo vibe going on at the local Methodist church. From this angle anyway.

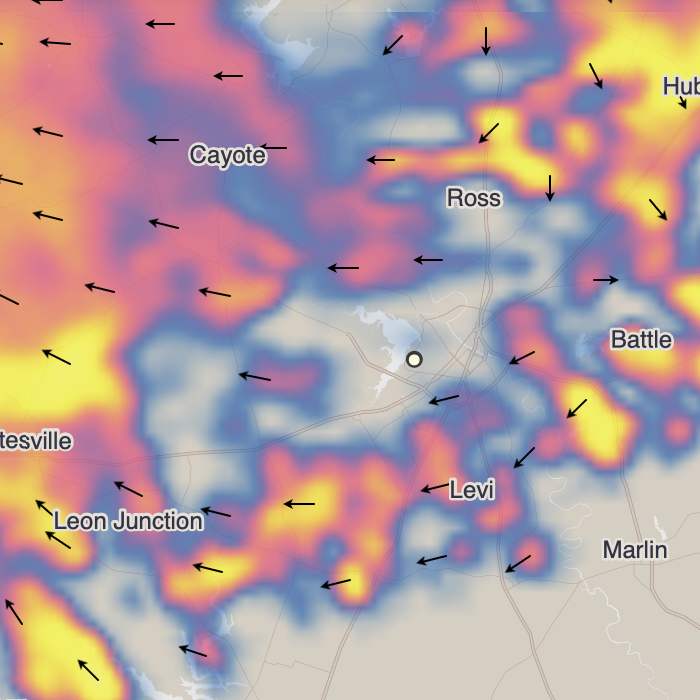

Rain everywhere … except in the little circle where I live. It’s like we have a force field keeping ALL rain away – and it’s been fully functional for two months.

I always quit Spelling Bee when I get to “Amazing,” because I think it would go to my head if I were called “Genius.”

Currently reading: Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston 📚

This is extremely uncomfortable for me, but over at my Buy Me a Coffee page I decided to ask people what might enourage them to offer more support. I figure that if I’m gonna ask people for money I need to find out what they want.

thoughts, nearing the end

The shot above is — in context — one of the most amazing things this amazing show has done.

If Rhea Seehorn doesn’t win an Emmy, there should be riots in the streets.

If Carol Burnett doesn’t win an Emmy, there should also be riots in the streets. Burnett, as famous as she is, has been an utter revelation as Marion.

Everything is unraveling fast, and it started unraveling when Francesca told Jimmy that Kim had called (in the aftermath of his disappearance at the end of Breaking Bad) to see if he was alive. That led him to call Kim, and that spectacularly disastrous decision led both of them to actions that will define the conclusion of the story they share.

Kim tells Jimmy that he should turn himself in, which infuriates him: he tells her that if she has a guilty conscience she should turn herself in — which she does. The chief effect Jimmy’s call has on Kim is to make her realize that all her attempts to finish the business of her life with Jimmy have proved unsuccessful — business remains, and that business is confession and atonement.

Meanwhile, in his rage Jimmy takes the opposite path: he resumes his downward spiral. He had dragged Jeff into a con because Jeff, a former resident of Albuquerque, had recognized him as Saul Goodman; once Jeff has committed a felony Jimmy can command his silence. He’s done with Jeff — until the phone call. Now — perhaps because he sees that he can never reconnect with Kim — he quickly becomes the worst version of himself, both unprecedentedly malicious and unprecedentedly careless. Once before he had unwisely gotten involved with “amateurs,” as Mike (in a flashback scene) calls Walt and Jesse, but then he was led by arrogance — he boasted that when he looked at Walt he saw 170 pounds of clay to sculpt; now he’s getting involved with amateurs again, but this time he’s driven by despair.

When Jeff recognized “Saul,” Jimmy called the Disappearer — but then, in mid-call, decided, “I’ll take care of this myself.” That may prove to be one of the unwisest decisions in a life full of unwise decisions. I don’t think he can make that call again. And I don’t think there’s a way out for him.

I’ll make two predictions for the finale. One, that everything will end, however it ends, for Jimmy and Kim alike, in Albuquerque; and second, that we’ll see one more flashback to Jimmy and Chuck — maybe in their childhood. Because Chuck understood his brother all along, understood him better than anyone. Several seasons back, he told Kim the necessary truth: “My brother is not a bad person. He has a good heart. It’s just … he can’t help himself. And everyone’s left picking up the pieces.” To her great misery, Kim found out just how right Chuck was. And she’s trying, one last time, to pick up those pieces.

Well, I’ve had more than enough of the heat, but this guy seems to like it.

exousia

The Greek word exousia (ἐξουσία) is one that develops in curious ways.

- In Plato its connotations are often (though not invariably) pejorative: for instance, in the famous story of the Ring of Gyges (Republic, Book II), the trait that Gyges exhibits in using the power of his ring so lavishly is exousia. It is a kind of license, a recklessness in exercising one’s own will without restraint.

- The Stoics, though, gave the word a positive spin. The great goal of the Stoic sage was freedom (eleutheria), and they actually defined freedom as a kind of exousia: “the authority of self-action” (exousia autopragias).

- In the New Testament the word has overwhelmingly positive connotations, and I am especially interested in its use to describe Jesus: “He spoke as one with authority” (ēn gar didaskōn autous hōs exousian echōn) — unlike the scribes and Pharisees. They have the institutional power, but he, this peripatetic sage and prophet, has the real authority. Also, the word often suggests speaking or acting in a way properly “authorized”: See Matthew 8:9 and especially Matthew 28:18: “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me” (Edothē moi pasa exousia en ouranō kai epi tēs gēs).

The more I think about this the more I see consistency rather than change in this history. Always, what exousia is depends on the character of the person exercising it. (A distinction we capture in English when we say authoritative or authoritarian.) Exousia in a selfish man, like Gyges, will produce vice; in a sage will produce freedom; in the Son of God will produce compelling teaching, a call to righteousness and intimacy with God. Exousia for Gyges yields self-gratification, while for the Stoic sage it yields self-fulfillment; but in Jesus it manifests itself in words of life for others.

Albert Murray in his apartment in Harlem, 1970s

Le Guin and forgiveness

Ursula K. Le Guin wrote very few bad stories, but among those few is, surely, The Word for World is Forest. And though she never called it a bad story, she knew that in it something had gone awry. In an introduction to the novella that she wrote some years after its first publication, she explains that she wrote it in a period in which she was much occupied with organizing and participating in demonstrations “first against atomic bomb testing, then against the pursuance of the war in Vietnam." And these were not pleasant times for her, because the protests against atomic bomb testing proved futile, and the situation in Vietnam was only getting worse, and the deterioration of that situation was accompanied by an increase in and intensification of lies from the government. She writes,

It was from such pressures, internalized, that this story resulted: forced out, in a sense, against my conscious resistance. I have said elsewhere that I never wrote a story more easily, fluently, surely – and with less pleasure.

I knew, because of the compulsive quality of the composition, that it was likely to become a preachment, and I struggled against this.

In parts of the story, and some of the characters, she feels that she succeeded in her struggle. But not in the case of the villain of the piece, a man named Davidson, a pretty transparent representative of the American military in Vietnam, just moved to a different planet. “Davidson is, though not uncomplex, pure; he is purely evil – and I don’t, consciously, believe purely evil people exist. But my unconscious has other opinions. It looked into itself and produced, from itself, Captain Davidson. I do not disclaim him.”

Her refusal to “disclaim” – it’s an interesting word – a character whose over-simplicity she acknowledges is an important thing. It’s like Prospero on Caliban: “This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine.” But it’s also a way of accepting the consequences of what, elsewhere in this same introduction, she designates as the strongest imperative of the artist: freedom.

She had sought and claimed for herself artistic freedom, the liberty to raise up characters from her own mind, and having exercised that liberty, she now sees that the results are not always what she would want, are not always admirable. Well. Such is freedom's price. In the last paragraph of her introduction, she writes:

American involvement in Vietnam is now past; the immediately intolerable pressures have shifted to other areas; and so the moralizing aspects of the story are now plainly visible. These I regret, but I do not disclaim them either. The work must stand or fall on whatever elements it preserved of the yearning that underlies all specific outrage and protest, whatever tentative outreaching it made, amidst anger and despair, toward justice, or wit, or grace, or liberty.

That’s an extraordinarily complex statement, and, moreover, one that I think is relevant to our own moment. Because what Le Guin understood, especially later in her career, looking back on her story in retrospect, is that “of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing is ever made," and therefore one’s own work will inevitably contain the residue of one’s own unresolved internal conflicts. And she forgives herself for any impurities in the story. (It’s noteworthy that she titled a later story-suite Five Ways to Forgiveness – I should do a post on those stories at some point.)

I have said before that our society is so miserable right now because it combines judgementalism with an inability to offer or receive forgiveness, which essentially means that every error is infinitely punishable. And it also means that in such an environment there can be no artistic freedom. Le Guin believed that a society in which artistic freedom is impossible is necessarily a sick society. And she was correct.

It’s common these days to believe that strict scrutiny — to borrow a legal term — must be applied to imaginative works to be sure that no wrongthink is published. But what if that scrutiny also impedes works of major creativity, works that enable new worlds of thought and sympathy? Unlike people on Twitter, Le Guin was an adult, and understood that every decision involves trade-offs: freedom to imagine and write and publish means that some of what is imagined and published is regrettable — even one’s own imaginings. She counted and cost, made her decision, and lived with the consequences. Like an adult.

It’s the cup of tea that just makes this one.

Photograph by Stanley Kubrick (1947) — taken, I think, with a Rolleiflex, because he used one often in those days. I do love me a square format camera.

Currently reading: Science and Government by C. P. Snow 📚

two quotations on church

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time:

The church was very exciting. It took a long time for me to disengage myself from this excitement, and on the blindest, most visceral level, I never really have, and never will. There is no music like that music, no drama like the drama of the saints rejoicing, the sinners moaning, the tambourines racing, and all those voices coming together and crying holy unto the Lord. There is still, for me, no pathos quite like the pathos of those multicolored, worn, somehow triumphant and transfigured faces, speaking from the depths of a visible, tangible, continuing despair of the goodness of the Lord. I have never seen anything to equal the fire and excitement that sometimes, without warning, fill a church, causing the church, as Leadbelly and so many others have testified, to "rock." Nothing that has happened to me since equals the power and the glory that I sometimes felt when, in the middle of a sermon, I knew that was somehow, by some miracle, really carrying, as they said, "the Word” — when the church and I were one.

Michael Warner, from his essay “Tongues Untied”, on listening to a lay teacher at his family’s Pentecostal church:

Every Wednesday night without fail, as this man wound himself through an internal deconstruction of the entire Calvinist tradition, in a fastidiously Protestant return to a more anthropomorphic God, foam dried and flecked on his lips. For our petit-bourgeois family it was unbearable to watch, but we kept coming back. I remember feeling the tension in my mother's body next to me, all her perception concentrated on the desire to hand him the Kleenex that, as usual, she had thoughtfully brought along.

Being a literary critic is nice, I have to say, but for lip-whitening, veinpopping thrills it doesn't compete. Not even in the headier regions of Theory can we approximate that saturation of life by argument. In the car on the way home, we would talk it over. Was he right? If so, what were the consequences? Mother, I recall, distrusted an argument that seemed to demote God to the level of the angels; she thought Christianity without an omniscient God was too Manichaean, just God and Satan going at it. She also complained that if God were not omniscient, prophecy would make no sense. She scored big with this objection, I remember; at the time, we kept ourselves up-to-date on Pat Robertson's calculations about the imminent Rapture. I, however, cottoned on to the heretical engineer's arguments with all the vengeful pleasure of an adolescent. God's own limits were in sight: this was satisfaction in its own right, as was the thought of holding all mankind responsible in some way.

enough is enough

It’s been said many times by many people, but the state of officiating in the Premier League is disgraceful — and does not appear to be improving. In today’s match between Brighton and Manchester United, there were several major errors, every one of which went in favor of the bigger club — which is par for the course in the PL, I’m afraid. Lisandro Martinez shoved Danny Welbeck right in the back in the box; no penalty, and VAR contrived not to see anything. Harry Maguire, already on a yellow, grabbed Leandro Trossard by the neck and threw him to the ground; ref didn’t see it, VAR didn’t look. Other calls were possibly defensible — an early offside call against Welbeck, a booking for Scott McTominay that probably should have been a red — but oddly enough, they went Man Utd.’s way also … and they still lost, which tells you what a shambles that side is right now.

As I’ve said many times, the ref in a modern top-level football match has an impossible job: the game is too fast and there are too many players. That’s why VAR exists — but in my experience, VAR gets calls wrong about as often as it gets them right. The Premier League makes so much money that it doesn’t care about any of this, but it ought to care.

Oh, one more thing: there’s talk that the VAR program will be turned over to the recently retired Mike Dean. Well, that would fix it! [cue maniacal laughter]

"One Manner of Law," by Marilynne Robinson:

Hugh Peters, most disparaged of Puritans, wanted to exclude poor artists from taxation. He proposed that there be peacemakers appointed to settle disputes before anyone could be arrested or imprisoned. Writing as someone who was forced to flee England under the threat of persecution, and whose fellow dissenters had experienced prison and worse, he does not call for any equivalent punishment or any punishment at all for his (temporarily) defeated persecutors, but instead for an alleviation of the punitive bent in the assertion of public authority.

A fascinating historical essay.