Finished reading: Space Odyssey by Michael Benson – one of the best books of its kind I’ve ever read 📚

Finished reading: The Railway Children by E Nesbit 📚 (first time in many years!)

What does my home town sound like? It sounds like Waxahatchee’s “Arkadelphia”. It sounds exactly like that.

Ross Douthat: “More Americans should live in the West, and more Americans assuredly will.” Yeah, they probably will, but they shouldn’t, because there’s not enough water.

Indeed, armed with a new toolbox of Latin names for fallacies, eager students all too often delight in spotting fallacies in the wild, shouting out their Latin names (ad hominem!; secundum quid!) as if they were magic spells. This is what Scott Aikin and John Casey, in their delightful book Straw Man Arguments, call the Harry Potter fallacy: the “troublesome practice of invoking fallacy names in place of substantive discussion”. However, they note another, less wholesome reason why some may be interested in fallacy theory. If one’s aim is not so much discovering the truth as winning an argument at all costs, fallacy theory can provide a training in the dark arts of closing down a discussion prematurely, leaving the impression that it has been won.

This, for Aikin and Casey, is the essence of what makes the straw man a fallacy: if we successfully “straw man” our opponent by knocking down a misstated version of their argument, we give the mistaken impression that the issue is closed.

Paradoxically, the straw man works particularly well on people well trained in the norms of good argument (the authors call this the “Owl of Minerva problem”: “we, in making our practices more self-reflective … create new opportunities for second-order pathologies that arise out of our corrective reflection”)…. Observers are generally more likely to be taken in by shoddy reasoning if they are already sympathetic to one side, and straw-manning contributes to the polarization of political debate. In today’s political environment it is not uncommon for partisans intuitively to see themselves as being on the right side of history, with their rivals adding nothing of value to the conversation and deserving of intellectual – or even moral – contempt. The prevalence of this fallacy in democratic political debate is thus a matter of significant concern: as Aikin and Casey write, it is “a threat to a properly functioning system of self-government”.

no nonsense

For the past few weeks I’ve been watching the 2022 UEFA European Women’s Football Championship, AKA the women’s Euros, and it’s been enjoyable throughout. And as much as the generally high quality of play — most notably from Arsenal legend Beth Mead — I have enjoyed the complete absence of drama-queen nonsense. I’ve been watching women’s footy for a long time, but not so much in so brief a period, and I think perhaps it’s the condensed timeline that has made me so aware of what’s missing: the flinging yourself to the turf, the rolling around in mock agony, the clutching of your face when an elbow grazes your bicep — the constant bullshit that really, seriously defaces the men’s game.

By contrast, these Euros have been all Chumbawamba: they get knocked down, they get back up again. They don’t get a call they want, they go on with the game. Sure, they let the ref know when they think a call has been missed, but essentially they just play footy. It’s been great.

At this point, I worry about how much longer it’s going to last. People like [my fiancé] — I think of them as “COVID virgins” — are becoming a rare breed. Just yesterday, President Joe Biden thinned their ranks by one more person. The Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation suggests that as of earlier this month, 82 percent of Americans have been infected with the coronavirus at least once. Some of those people might still think they’re never had the virus: Asymptomatic infections happen, and mild symptoms are sometimes brushed off as allergies or a cold. Now that we’re battling BA.5, the most contagious and vaccine-dodging Omicron offshoot yet, many people are facing their second, third, or even fourth infections. That reality can make it feel like the stragglers who have evaded infection for two and a half years are destined to fall sick sooner rather than later. At this point, are COVID virgins nothing more than sitting ducks?

“Destined to fall sick” — or not, depending on how common asymptomatic or nearly-asymptomatic infections are. But how can we know how common they are, since not many people who have no symptoms are likely to get tested. I don’t think I’ve had COVID, but who knows? Maybe I’ve had it once or twice or even more, but am one of the super-lucky ones. Nobody knows anything, basically.

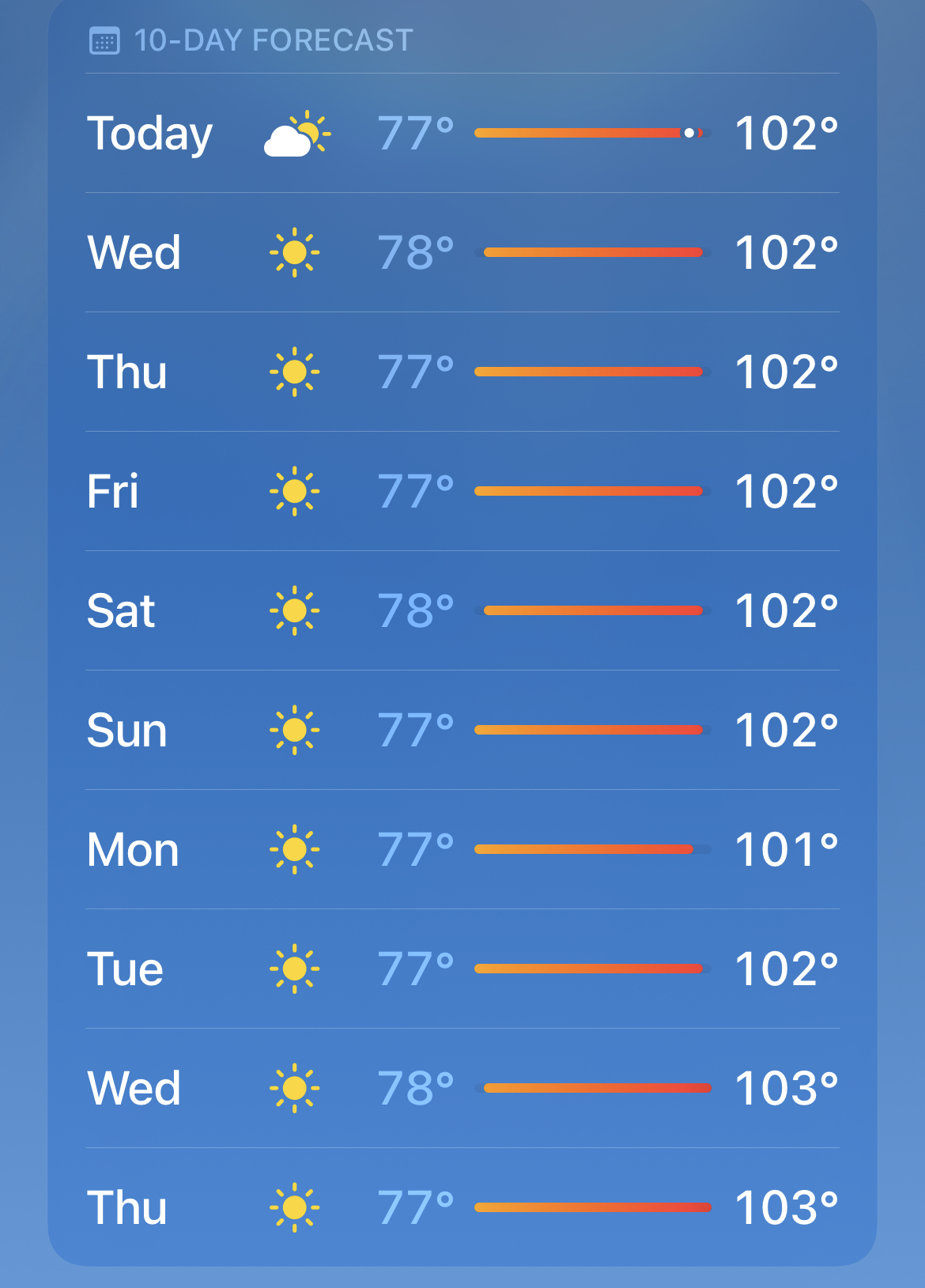

We only have one weather now.

two varieties of human frailty

Breaking Bad is a story about ressentiment; about a man who feels himself marginalized and neglected, powerless and ineffectual, who, therefore, cannot resist the temptation to establish himself as a Power — as a man who says, and means it: “I am the one who knocks.”

Better Call Saul dramatizes a radically different form of human frailty: the temptation of the con. The person so tempted may be socially marginal or socially dominant or something in between — though the marginal will have a few more incentives pushing them towards scamming. What’s at work here is not ressentiment but rather (a) a desire to dominate people, a desire to know what they don’t know and act on that knowledge in a way that enables you to triumph over them, and (a) the intellectual challenge of building a successful scam: the meticulous planning, the anticipation of the responses of your marks, the ability to improvise when things go wrong. What you see in Better Call Saul is, first, how the power of these two motives — the desire to dominate and the love of intellectual challenge — vary from person to person, and within a person from moment to moment; and also the crack-like addictiveness that follows upon the running of a successful scam.

Both shows then are about extremes of human frailty — frailty become perversity, perversity become wickedness — and how inescapable the associated habits of thought and action can be.

normie wisdom 7: politics

Towards a Normie Politics - Freddie deBoer:

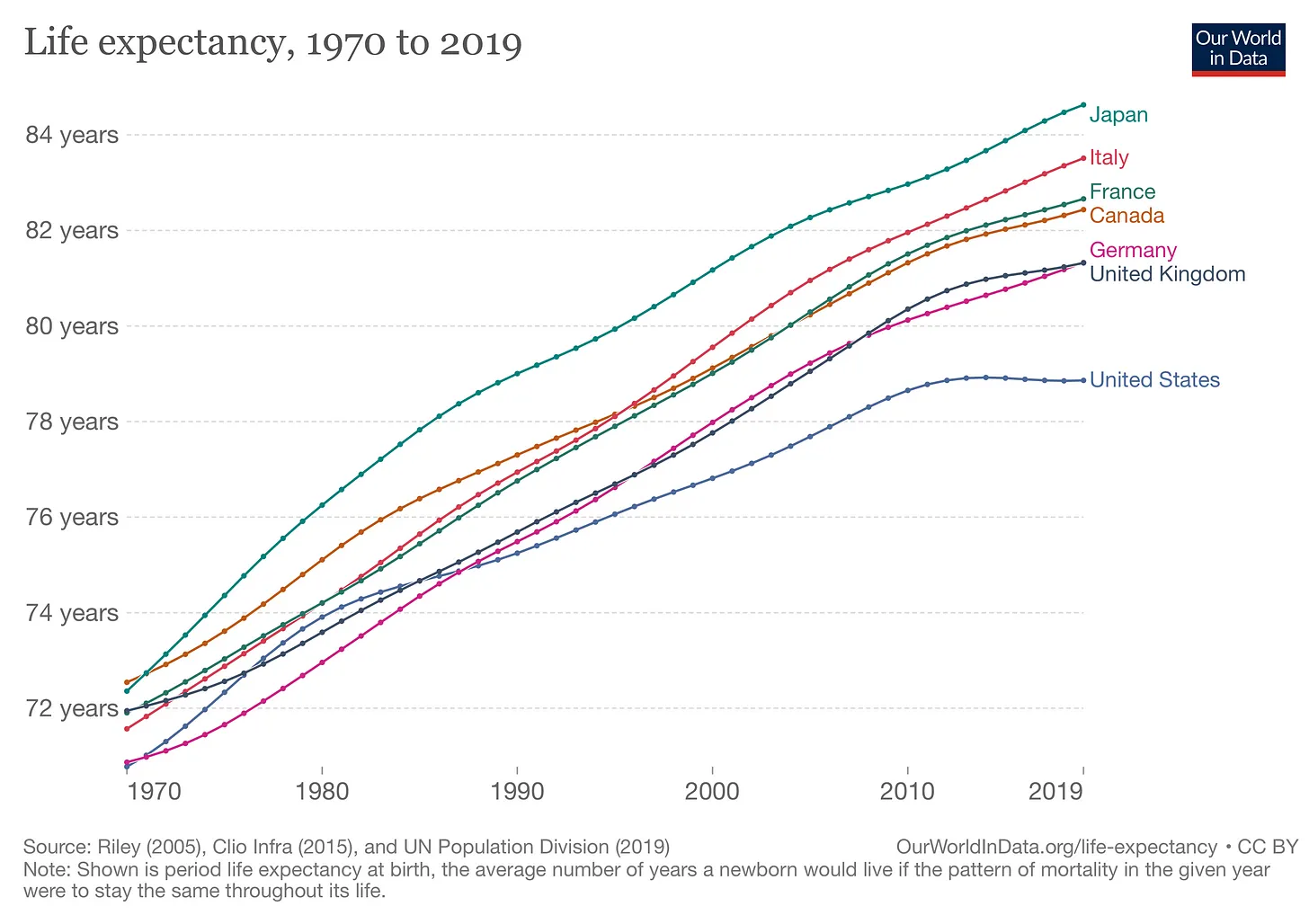

The association with the mainstream and centrism in American political life depends on a very selective view of the normal. The current state of affairs in American healthcare, for example, is not remotely left-wing and also not remotely “normal,” compared to other developed countries, especially in terms of our costs and bad outcomes. Normie politics allow for far-left alternatives, if they are presented intelligently. Fetterman, after all, supports Medicare for All, a radical (and badly needed) proposal to rip America’s system for funding healthcare up from its roots. The viability of this proposal is of course fiercely debated, but it enjoys consistently strong polling support, and benefits from its great moral simplicity: tax people more and let the government fund everyone’s healthcare. This is a far-left goal, but it’s quintessentially normie politics. In contrast, I would say that Obamacare’s bewildering subsidies and exchanges and tiers of coverage stand as the antithesis of normie politics. In contrast to normie politics, Obamacare was the apotheosis of wonk politics, politics for people who ride the Acela every day. In other spaces, the normie demand might indeed be more centrist than alternatives, but it’s fundamentally not the centrism that makes politics normie. It’s the constant return to framing that emphasizes the comfortable and the mundane.

Bernie Sanders’s insurgent campaigns in 2016 and 2020 failed, but they dramatically outperformed what was expected of an avowed socialist, in no small measure because Sanders is one of the most effortlessly down-to-earth politicians in modern history. Bernie is down-to-earth, but I would phrase Freddie’s point slightly differently. If you reflect on, for instance, the way a Fox News audience in 2016 responded to Bernie, you can see that the key thing is not so much being down-to-earth but rather his communicating something essential to that audience: I care about the same things you do. He cares about people having to work for below-subsistence wages, he cares about people who can’t get access to higher education, he cares about not leaving an environmental mess for our children. Basic stuff. Normie stuff.

Probably the typical Fox viewer is skeptical of Bernie’s proposals for dealing with all that stuff, but they can’t deny that he’s asking the right questions and raising the right issues. Which means that he at least has a chance to win them over to his proposals; whereas when Joe Biden says that “Transgender equality is the civil rights issue of our time,” he’s just alienating people he can’t afford to alienate – including Black voters who wonder when, exactly, the civil rights of Black Americans got totally sorted out.

As I have said many times, I am dispositionally a conservative, but that just makes me homeless in our current political landscape. If we had a genuine Left — not the virtue-signaling cosplaying on social media with its limited roster of mindless buzzwords, but a Left that draws on its own best history of caring for the insulted and the injured, the downtrodden and the hopeless — this dispositional conservative would find that a lot more appealing than the politics of ressentiment and hatred that the Republican Party now largely embraces. But, you know, if a frog had wings he wouldn’t whomp his ass every time he jumped.

To people who say that they need to repair and renew and restore themselves before they turn their attention to anything else -- which is what one person said to me recently -- I would reply that turning your attention to cultural products that are good and true and beautiful is a way of renewing your attention by redirecting it, and therefore beginning to heal yourself. To give yourself the food that your spirit needs is at one and the same time to renew yourself and to renew your cultural enframing, as it were. To listen to a beautiful piece of music and then share it with others, is to heal yourself, offer healing to them, and do justice to someone’s meaningful work. It is a triangulated renewal.

Currently reading: The Common Expositor: An Account of the Commentaries on Genesis, 1527-1633 by Arnold Williams 📚

How to Search for Life on Mars — The New Atlantis:

Despite what it says, NASA has actually made the decision not to look for present life on Mars, even though tools that could identify life have been available to the agency for twenty years. Even worse, NASA’s existing rovers operating on Mars are being directed to avoid areas most likely to harbor life, and its plans for future human exploration are being designed in a way that would minimize their exploratory capability.

What in the world is NASA thinking? And how can we get the agency back on the path to finding life?

A fascinating essay, and a kind of case study on how bureaucracies evaluate risk vs. reward.