Metafoundry 75: Resilience, Abundance, Decentralization:

We mostly only close materials loops when it’s ‘economically viable’ to do so. By and large, what that means is that it takes less energy to recycle the material than it does to create it in the first place, which is true for aluminum, steel, and glass, but not for materials like plastics or concrete. But the promise of access to renewable energy is that it changes this equation, putting processes that are intrinsically energy-intensive, like recovering the carbon from plastics for reuse or desalinating seawater to make it potable, on the table. It doesn't matter how much energy a process needs if it is inexpensive, doesn’t limit the energy available to others for their use, and is non-polluting. There's a virtuous circle here too: the faster that renewable energy systems are up and running, and the closer we can get to achieving this potential, the more that we can apply that clean energy to repurposing the materials of our current technological systems to build out the physical infrastructures of our new ones. Not beating swords into plowshares, but recycling cars into electric trams. We live on a sun-drenched blue marble hanging in space, and for all that we persist in believing it's the other way around, that means we have access to finite resources of matter but unlimited energy. We can learn to act accordingly.

I don’t know anyone smarter than Deb Chachra. Please read the whole letter.

Currently reading: Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams — the Early Years, 1903-1940 by Gary Giddins 📚

cross and resurrection

If the cross were the last word in God's self-revelation, then this first commentary would be the only possible one. If all humankind — even in its best representatives — is exposed here as one murderous treason against its Creator, what future is there but death? What is the point of continuing this futile saga of sin, even with all the adornments of civilization? If the Cross is the end, then there is no future.

But it is not. The resurrection is the revelation to chosen witnesses of the fact that Jesus who died on the cross is indeed king-conqueror of death and sin, Lord and Savior of all. The resurrection is not the reversal of a defeat but the proclamation of a victory. The King reigns from the tree. The reign of God has indeed come upon us, and its sign is not a golden throne but a wooden cross.

Currently reading: The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood by David Thomson 📚

the great and awful doctrine

The great and awful doctrine of the Cross of Christ, which we now commemorate, may fitly be called, in the language of figure, the heart of religion. The heart may be considered as the seat of life; it is the principle of motion, heat, and activity; from it the blood goes to and fro to the extreme parts of the body. It sustains the man in his powers and faculties; it enables the brain to think; and when it is touched, man dies. And in like manner the sacred doctrine of Christ's Atoning Sacrifice is the vital principle on which the Christian lives, and without which Christianity is not. Without it no other doctrine is held profitably; to believe in Christ's divinity, or in His manhood, or in the Holy Trinity, or in a judgment to come, or in the resurrection of the dead, is an untrue belief, not Christian faith, unless we receive also the doctrine of Christ's sacrifice. On the other hand, to receive it presupposes the reception of other high truths of the Gospel besides; it involves the belief in Christ's true divinity, in His true incarnation, and in man's sinful state by nature; and it prepares the way to belief in the sacred Eucharistic feast, in which He who was once crucified is ever given to our souls and bodies, verily and indeed, in His Body and in His Blood. But again, the heart is hidden from view; it is carefully and securely guarded; it is not like the eye set in the forehead, commanding all, and seen of all: and so in like manner the sacred doctrine of the Atoning Sacrifice is not one to be talked of, but to be lived upon; not to be put forth irreverently, but to be adored secretly; not to be used as a necessary instrument in the conversion of the ungodly, or for the satisfaction of reasoners of this world, but to be unfolded to the docile and obedient; to young children, whom the world has not corrupted; to the sorrowful, who need comfort; to the sincere and earnest, who need a rule of life; to the innocent, who need warning; and to the established, who have earned the knowledge of it.

One more remark I shall make, and then conclude. It must not be supposed, because the doctrine of the Cross makes us sad, that therefore the Gospel is a sad religion. The Psalmist says, “They that sow in tears shall reap in joy;” and our Lord says, “They that mourn shall be comforted.” Let no one go away with the impression that the Gospel makes us take a gloomy view of the world and of life. It hinders us indeed from taking a superficial view, and finding a vain transitory joy in what we see; but it forbids our immediate enjoyment, only to grant enjoyment in truth and fulness afterwards. It only forbids us to begin with enjoyment. It only says, If you begin with pleasure, you will end with pain. It bids us begin with the Cross of Christ, and in that Cross we shall at first find sorrow, but in a while peace and comfort will rise out of that sorrow.

Ross's prediction and mine

I will make a prediction: Within not too short a span of time, not only conservatives but most liberals will recognize that we have been running an experiment on trans-identifying youth without good or certain evidence, inspired by ideological motives rather than scientific rigor, in a way that future generations will regard as a grave medical-political scandal.I think this prediction will partly, but not wholly, come true. I do believe that there will be a change of direction, but for the most part it will be a silent one, an unspoken course correction; and on the rare occasions that anyone is called to account for their recklessness, they’ll say, as a different group of enthusiasts did some decades ago, “We only did what we thought was best. We only believed the children.” But they won’t have to say it often, because the Ministry of Amnesia will perform its usual erasures; and even the children who have been sacrificed on the altar of their parents’ religion, metaphysical capitalism, may not recognize or remember what was done to them.

The same will be true of those who suffer the various derangements in what passes for the Right today. People will later briefly wonder at “all that happened to us, around us, and by us” — but then a notification will hit their phone and the wondering will cease. And the demonic realm will persist in its sleepless labor.

I’ll be back after Easter.

waiting for persuasion

Leon Wieseltier’s long essay on postliberal Catholic integralists, or whatever we should call them, is a mixture of the insightful and the dismissive. (When he writes, “The difference between theology and philosophy is that philosophy inspects the foundations, whereas theology merely builds on them,” that just tells you how little theology he has read.) Mainly Wieseltier demonstrates how different the integralists’ core commitments are from his — but then we knew that already, didn’t we?

In “Vespers,” the fifth of Auden’s “Horae Canonicae,” the poet imagines a brief crossing-of-paths in the city, at dusk: he, the nostalgic Arcadian, passes his “antitype,” the Utopian. “When lights burn late in the Citadel,” the poet thinks, “Were the city as free as they say, after sundown all her bureaus would be huge black stones”; but the Utopian thinks, “One fine night our boys will be working up there.” The integralists are in this sense Utopian: they think of power chiefly to long for it.

They tell us what they’ll do when their boys occupy the Citadel; but what they never tell us, as far as I have been able to discover, is how they plan to get there. It’s perhaps understandable that they’re not trying to persuade Leon Wieseltier; but they’re not even trying to persuade me. They’re just talking to one another. Were they ever to begin seeking allies I might well pay close attention; but not until.

discounting the past

People on the left will typically be amazed and gratified by any good that has been achieved recently, and will treat any goods achieved by our ancestors as matters of course for which none of us need be grateful. Likewise, they are predisposed to see new developments as goods and are therefore unlikely to criticize them.

People on the right will typically be obsessively horrified by any new wrong, and uninterested in wrongs that have been long embedded in our social order — indeed, they will be so predisposed to see new developments as ills that they may, by way of compensation, grow inclined to see old ills as positive goods. But even if they see the ancient wrongs for what they are, they won’t feel their seriousness; it’s the new wrongs that engage their emotions.

In both cases, the looming power of the present moment distorts our judgment. Neophilia and neophobia alike occur because the present is so BIG that we can’t see around it; or because everything not-now seems small in comparison.

In other words, just as there are social discount rates for the future, there are also social discount rates for the past. And in both cases, our media environment encourages stronger and stronger discounts as we move away from the present moment (something that remains true even when the media try to tell us about climate catastrophe). But because the future has not occurred and could take many forms, it remains fuzzy for us, whereas the past can be seen more clearly. So I think that if we want people to have a stronger regard for future — to discount it less heavily — then, paradoxically, we need to make people more attentive to the past, its errors and its achievements alike.

self-Haysing

As Nikil Saval pointed out some years ago, “The arc of scientific management is long, but it bends towards self-Taylorizing.” (See further development of these ideas in this essay by Alexa Hazel, and a few comments by me, on related matters, here.)

I might coin an analogous phrase: The arc of creative product development is long, but it bends towards self-Haysing.

For several decades the Motion Picture Production Code, commonly known as the Hays Code, governed what could and could not be shown in movies. I was thinking of it the other day while watching Ernst Lubitsch’s glorious Trouble in Paradise (1932), made just pre-Code and therefore full of Inappropriate Content.

A very funny moment early on comes when the two thieves-pretending-to-be-aristocrats, played by Miriam Hopkins and Herbert Marshall, are having dinner together and gradually revealing what they’ve pinched from each other. He returns her brooch; she returns his watch. They resume their meal and then after a moment he says, “I hope you don’t mind if I keep your garter.” Her eyes widen and her hand inspects her leg as he displays the garter, kisses it tenderly, and replaces it in his pocket.

The Hays Code did away with such immoralities. Eventually it was repealed in favor of our current movie rating system, and now we can have anything, right? Right? Well....

Alan Rome has a fine essay in The New Atlantis on recent developments in the Star Trek world in which he points out that earlier installments in the series were governed by a kind of liberal idealism: “In Star Trek’s future, the United Federation of Planets is a liberal-democratic regime encompassing hundreds of different alien species, all devoted to peace, freedom, and equality. The Federation is the United Nations writ galactic, led by an Americanized humanity.” But more recently it has become necessary to cast strong doubt on all that nonsense: “Government is somehow both the only possible guarantor of justice and also structurally implicated in all social evils. The current system is therefore illegitimate and needs to be dismantled in favor of some sort of utopian solution.” That no one seems to know what that Utopia might look like is another of Rome’s points, but for now I just want to focus on the fact that a series like Picard cannot do anything but portray any existing social system as hypocritical, complicit in oppression, structurally unjust, etc. etc. That’s intrinsic to the Code.

As Foucault spent his career demonstrating: Written Codes are strong, but Codes unwritten are stronger. And I don’t think I need to list the ways in which recent movies and TV shows have exhibited a frantic determination to depict all that Must Be Shown and to refrain from depicting all that Must Not Be Shown. I also don’t think I have to list the ways in which this kind of manaical ticking of checkboxes inhibits creativity. It’s self-Haysing: disciplining yourself in order to avoid being disciplined by others, and that’s always kind of pathetic. No need to belabor this point. I just want to make a few others:

- Whether written or unwritten, Codes are always present, though some periods (like our own) are more prone to code fetishizing than others;

- While you will surely approve of some Codes and disapprove of others, they always inhibit creativity;

- But they also inspire creativity, because real artists look for ways to evade the force of Codes or, through jujitsu moves, use them to advantage;

- Figuring out whether in any given case a Code is more productive than destructive is not easy, though as a general rule, the more feverishly people strive to enforce a Code the more destructive it is;

- And, finally, if you don’t like what the current Code is doing to movies and TV, there’s a vast body of work out there that you’ll like better.

I don’t know why people think it’s so important that there are always new products being developed that will suit them. If there’s one thing that our current moment does well, it’s to make available to us the great cultural achievements of the past, in multiple forms and formats. If I don’t like Old Disney, there’s Woke Disney; if I don’t like Woke Disney, there’s Old Disney. Break bread with the dead, is what I say. (But also maybe stock up, just in case.)

Currently reading: Tristes Tropiques by Claude Levi-Strauss 📚

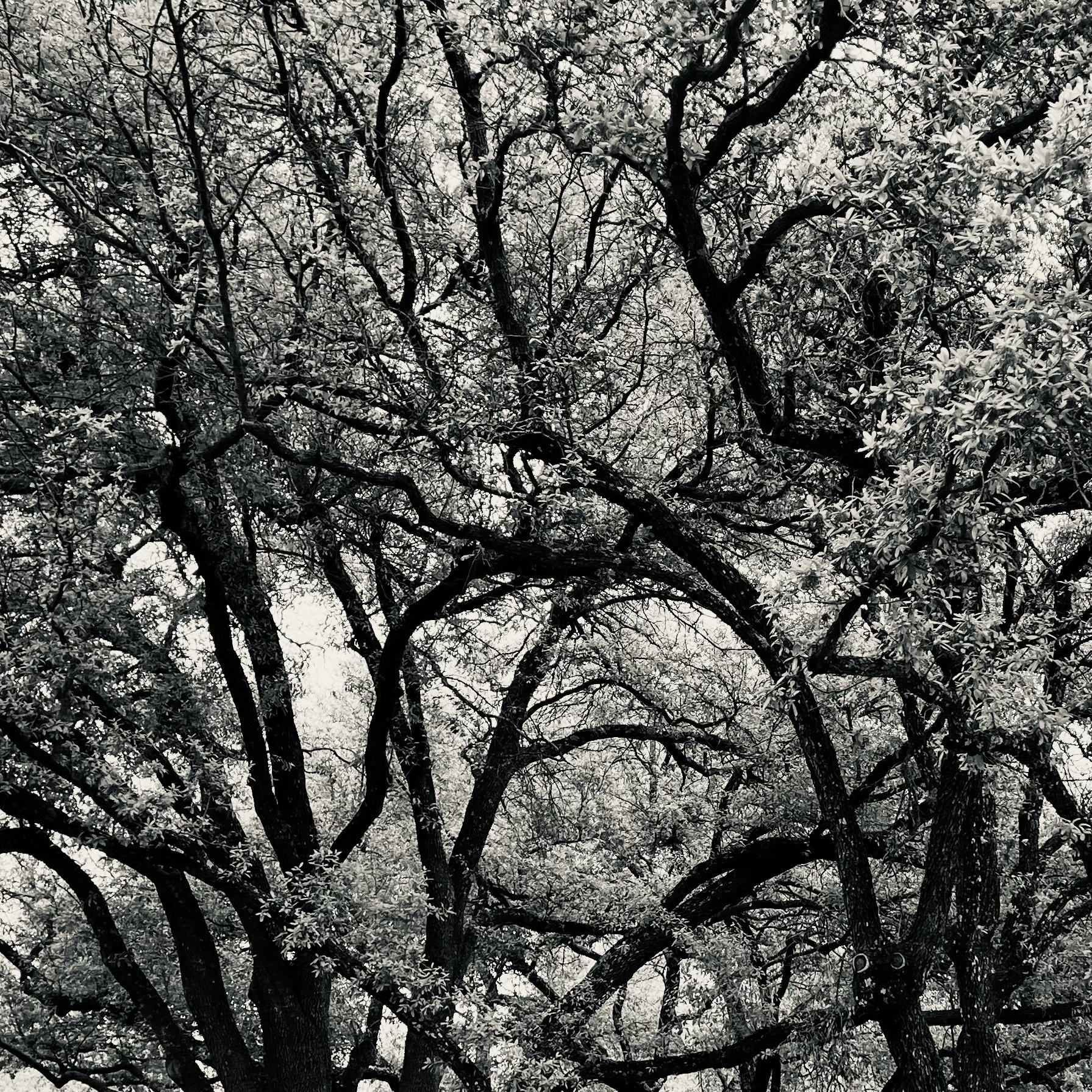

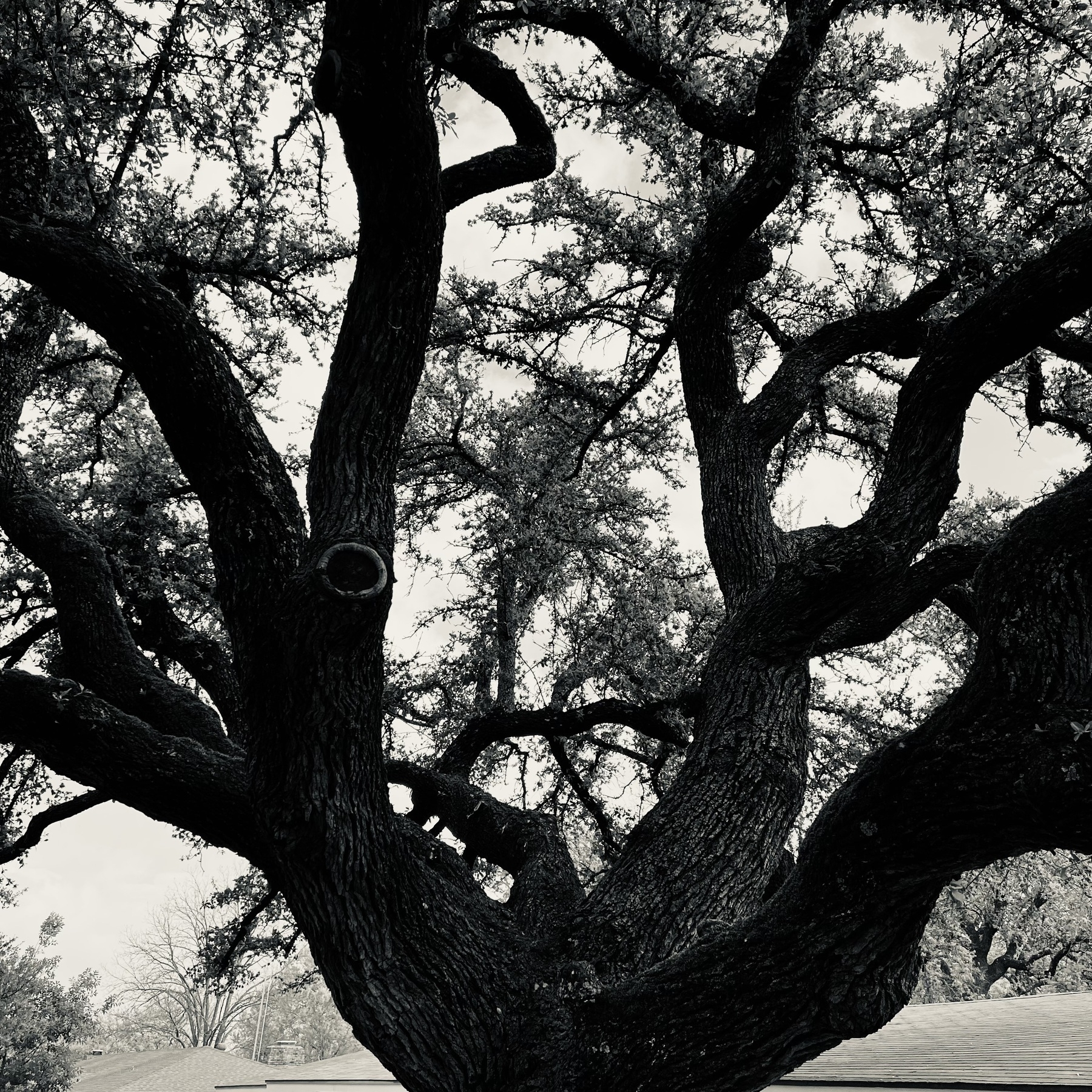

We have four mature live oaks on our property, but this is the one I look at the most often. It has a curiously sinuous interior architecture.

The Cosmati Pavement in Westminster Abbey: “In the year of Christ one thousand two hundred and twelve plus sixty minus four, the third King Henry, the city, Odoricus and the abbot put these porphyry stones together. If the reader wisely considers all that is laid down, he will find here the end of the primum mobile.” From a story in the Guardian: “Only a handful of brass letters remains of the original long inscription, but it was transcribed centuries ago. It names the king, the chief craftsman as Odoricus, gives the date in a tortuous riddle, and then mysteriously suggests that the world will last for 19,683 years, by adding together the life spans of different animals: "add dogs and horses and men, stags and ravens, eagles, enormous whales….”

Demons

I got a lot of problems with you people, and you know what the top one is? Many of you are possessed by demons. Or at least oppressed by them. And it needs to stop.

But as always, the first step is acknowledging that you’re afflicted by powerful forces beyond your control. So I try to lay out my demonology in this essay.

You’re welcome.

I do like a frittata.

I saw this lovely old thing at a friend’s house the other day.