NBA players feature a range of visible accoutrements: headbands, full sleeves, elbow sleeves, knee sleeves, full-length leg sleeves, wristbands. That’s why I always notice the few players who are True Basic. Evan Mobley, for instance: top, shorts, socks, shoes — that’s it. I can’t even see any tats. Impressive! 🏀

FYI, when something appears that’s relevant to a post of mine, or when I simply have further thoughts, I will often update the original post accordingly. I’ve done that recently with posts about

I wrote about why LLMs, and their makers, don’t care about thinking.

“We must now say, ‘I am Pope Francis.” But I am not Pope Francis. I am Spartacus.

“When we read too quickly or too slowly we understand nothing.” — Pascal

I’ve updated my post on Harvard’s conflict with our President with a couple of interesting quotations.

If personal growth were only for children, it would be a mistake to look to parent-child relations for general insights into the dynamics of love. But growth does not stop when one reaches what is misleadingly called “the age of maturity.” We humans are distinguished by the fact that our potentiality is gradually given over to us, as our charge, so that the good does not merely provide us with our proper measure but also with our calling, our lifelong task. Having been born into the human world, we are called to carry on with the work of birthing, slowly hatching the human being we are called to become. The younger self must help give birth to the older self, in the medium of its own future. This means that our younger selves are called upon to parent a child whose wisdom we hope will exceed our own. To do this we must draw upon our own half-formed insights, along with whatever guidance we can find in the wider human world, to actualize goods that as yet we can see only hazily, in hopes that eventually we will see them more clearly.

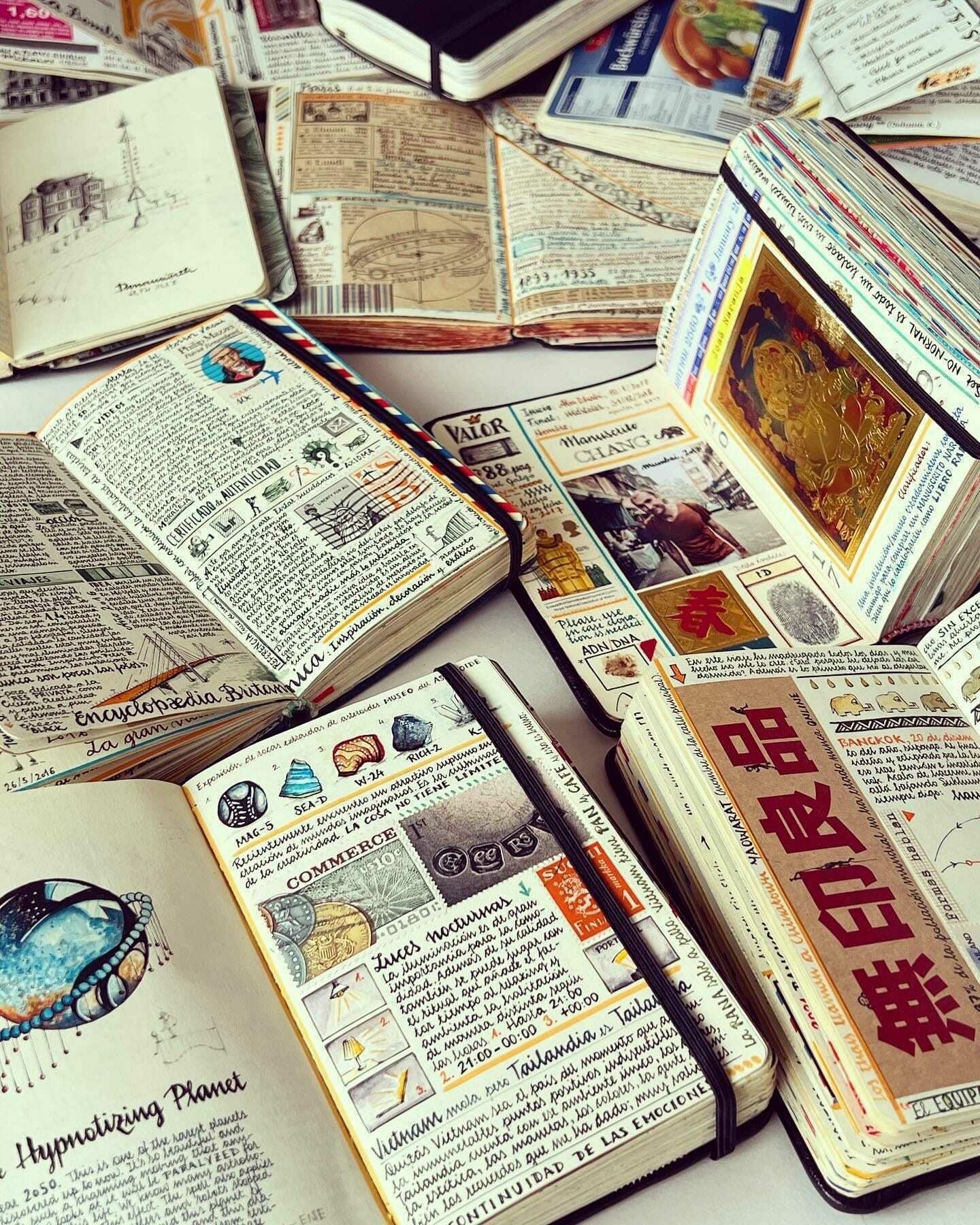

My envy of what José Naranja does is profound.

Ross Douthat’s recent “Age of Extinction” column is vital:

This isn’t just a normal churn where travel agencies go out of business or Netflix replaces the VCR. Everything that we take for granted is entering into the bottleneck. And for anything that you care about — from your nation to your worldview to your favorite art form to your family — the key challenge of the 21st century is making sure that it’s still there on the other side.

It’s also a neat summation of what I am trying to do on The Homebound Symphony and in my other writings. I hope to have more to say about it soon.

Hoping for adventure (as always)

A few thoughts on Pope Francis — lux aeterna luceat ei — and his successor.

Yet one thing that is true about the Haggadah is that it is emphatic about liberation being in God’s hands. That’s why the text very nearly erases Moses from the story. Over and over, the text says, liberation from Egypt was something God did for me, not something I won or that was handed to me by some lesser mortal savior. In this populist era, where both Trump and Netanyahu style themselves kings and messiahs, that’s one reason I can still put forward confidently for clinging to the traditional text, even at the risk of being irrelevant.

Holy Week recommendation: the Netherlands Bach Society performing the St Matthew Passion. ✝️ 🎵

Brad Mehldau’s cover of “Little Person” is just sublime. 🎵

My friend Jim Beitler on Tolkien, Lewis, George Herbert, and trees.

Not really interested in the Bauhaus Clock screensaver, but if it were based on John Harrison’s H4 I’d be saying TAKE MY MONEY.

I’ve got a post up on Harvard’s argy-bargy with the Administration — mainly quotations, which I’ll probably be adding to.