Another Houston treasure: the Beer Can House

The Electric Ladyland car, from the Houston Art Car Parade

I wrote about green tea and mescaline — and other ways of opening doors to the demonic.

Dana Gioia, 2003:

Although conventional wisdom portrays the rise of electronic media and the relative decline of print as a disaster for all kinds of literature, this situation is largely beneficial for poetry. It has not created a polarized choice between spoken and printed information. Both media coexist in their many often-overlapping forms. What the new technology has done is slightly readjust the contemporary sensibility in favor of sound and orality. The relation between print and speech in American culture today is probably closer to that in Shakespeare’s age than Eliot’s era — not an altogether bad situation for a poet. For the first time in a century there is the possibility of serious literary poetry reengaging a non-specialized audience of artists and intellectuals, both in and out of the academy. There is also an opportunity of recentering the art on an aesthetic that combines the pleasures of oral media and richness of print culture, that draws from tradition without being limited by the past, that embraces form and narrative without rejecting the experimental heritage of Modernism, and that recognizes the necessary interdependence of high and popular culture. A serious art does not need a large audience to prosper — only a lively, diverse, and engaged one.

I wrote about the 1938 film of Shaw’s Pygmalion — and especially about Wendy Hiller’s amazing performance as Eliza. 🎥

Even though I am certainly angry at those students who choose to cheat, the fact is that I also care about them and feel a certain degree of compassion for them. I don’t want them to miss out on the opportunity to become educated, not even as the result of their own poor choices. It’s a bit of a Catch-22. How can we expect them to make good choices, about their studies or anything else, if they have not yet been given the tools to think critically? How can we expect them to grasp what education means when we, as educators, haven’t begun to undo the years of cognitive and spiritual damage inflicted by a society that treats schooling as a means to a high-paying job, maybe some social status, but nothing more? Or, worse, to see it as bearing no value at all, as if it were a kind of confidence trick, an elaborate sham?

Deep reading means first of all close reading: the scrupulous examination of the text for patterns of language and image, narrative structures and strategies, manipulations of generic expectations, formal balances and juxtapositions, allusions, concealments, ambiguities, and anything else you can find, then the further attempt to interpret them. The afternoon the students arrived, I handed out a sheet with some orienting material. At the top, I put two quotations. The first was from David Neidorf, the former longtime president of Deep Springs College: “To read a book truly is to cooperate with its effort to teach you something.” The second was from Ursula K. Le Guin: “The artist deals with what cannot be said in words. The artist whose medium is fiction does this in words. The novelist says in words what cannot be said in words.” Says it, that is, like all art, through form, which it is the purpose of close reading to expound.

Reading is time well-spent and since time is a vanishing resource, getting the most of it must be a fundamental human goal. In this age of Big Tech and artificial encroachment, I view reading a book as a small act of rebellion. I can coexist fine with technological advancement but I won’t be subsumed by it. I won’t submit, day and night, to the supercomputer in my pocket. Ultimately, today’s tech must be viewed with a degree of healthy hostility because it is savagely addictive. It is not, despite the utilitarian bent of its creators, terribly utilitarian. Electricity, the automobile, the airplane—these were meant to provide, not enslave, even when they brought negative consequences like pollution and climate change. We are in a new world, one where we must assume the worst when it comes to the purveyors of our newest tech. We must, in our own ways, rebel, and not be amused to death. Reading is worthwhile for its own sake. It offers pleasure. I am not sure what it does for character—many insidious people throughout history have read books—and I do not know if someone lacking empathy can acquire it through a novel. What reading does do is make demands of the individual. It is active, not passive, and the act of reading wills an imagination into being. The imagination is the greatest muscle of all, one that must never be allowed to atrophy away.

Future me (from the Dylan subreddit)

“I See the Birds” — beautiful new song by Jon Guerra. If only more devotional music (that’s Jon’s phrase for what he does) sounded like this.

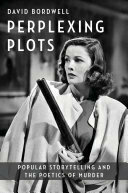

Finished reading: Perplexing Plots by David Bordwell. A really remarkable book, which argues — employing an astonishingly wide range of examples — that the kinds of narrative experimentation typically associated with avant-garde literature was in fact largely pioneered in pop culture: genre fiction, movies, radio drama, etc. 🎥

My father in Christ really knows how to put the spiritual pressure on.

I am unusually sensitive to loud and abrasive sounds, so I am particularly interested to see how sound design can contribute to calm environments (or, more often, contribute to my misery).