David Thomson: “This is the great American film about the highest artistic dreams leading you to madness.” 🎥

Finished reading: Lonely Magdalen by Henry Wade. A remarkable Golden Age detective novel that starts as a police procedural, then around halfway through turns into a social novel about events from twenty years earlier — then becomes a procedural again. It reminds me in several ways of Ian McEwan’s Atonement. 📚

How do we distinguish our ordinary suffering from the unacceptable, and what do families and cultures and states do about it? Philosophical and ancient wisdom traditions are ready with insight, but schools don’t teach these domains. So we stretch the logic of accommodations far beyond what it can hold. We speak in the thinnest therapeutic language for all our troubles. We resign ourselves to the ever-receding goalposts that hold something like “belonging,” because we can’t imagine shoring up forms of life outside the machines-and-markets shape of the modern world.

It would be possible — and highly desirable — to build a large intellectual/practical project around this single insight. A project involving scholars, writers, artists, medical practitioners, and maybe especially therapists (who need the insights here more than almost anyone else). Jointly funded by the Templeton and Gates foundations.

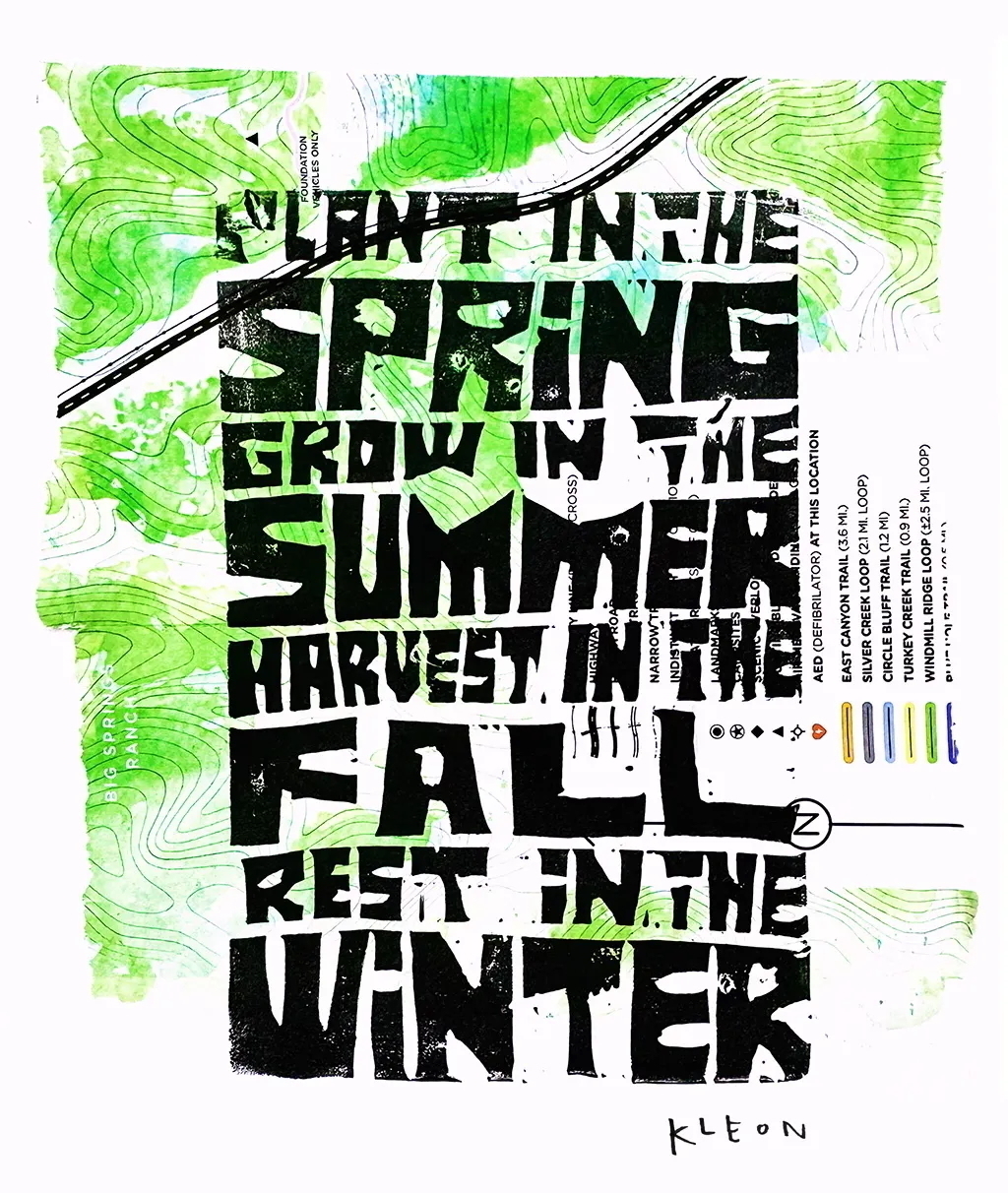

Austin made this at the Laity retreat last week. So great to hang with him. What a smart, funny, talented guy.

I’ve been trying to figure out how I might resume my thoughts on Douthat’s thoughts on belief, and I’m still musing, but I got a big boost to that musing this morning from this post by Noah Millman.

A usefully long piece on our our cities ended up with so many “aesthetically forgettable but highly profitable buildings.”

Noticing that Jeff Tweedy and A. C. Newman have Substacks now, I’m starting to think that I’m the last person over fifty who doesn’t have a Substack.

I wrote, and then updated, one last post on the ridiculous current kerfuffle about Wheaton College.

Recently on Mac, Spotlight has been failing miserably. I’ll search for a term that appears in dozens of filenames and Spotlight will return two or three, or sometimes none at all. HoudahSpot finds everything, which is great, but I shouldn’t have to buy a 3rd-party app for basic file searches.

Here’s my friend Jono Linebaugh with a lovely reflection on mercy, drawing on Auden’s great long poem The Sea and the Mirror. (I should do an online class about that poem one of these years.)

Mary Harrington on speaking at the recent Alliance for Responsible Citizenship conference at London’s ExCel Centre:

As for Excel, I wasn’t the only person to remark on the disjunction between the conference centre’s paradigmatic expression of the nomos of the airport, and the humanising story the conference itself sought to bring to contemporary political and social questions. Perhaps all we can really say to this is, a little tritely, we are where we are and the options for accommodating that many people for a conference are both limited and, more or less by definition, ordered to that nomos.

Maybe those of us who protest the dehumanizing shape and scale of this late modernity we’re living in shouldn’t have conferences of that kind. Maybe it’s not possible to think outside the confines of metaphysical capitalism when you’re operating wholly within the structures of that nomos.

After this year’s first session of playing in the garden hose.

Muñoz’s lecture is itself a long and challenging one. He had to spend a long time at the lectern to deliver it, and the audience had to sit a long time in their chairs to hear it. The reader of the transcript, too, has to devote a long time to reading it. What we have here is a kind of reciprocity of courtesies. The paying of attention — to a painting, to a lecture, to an essay, to a person, to anything — is also always a paying of courtesy. In paying attention we pay respect.

I wrote about what to do when you think an author might be racist — or otherwise morally deficient.

This new post by Timothy B. Lee is exemplary. Lee is the best guide I’ve found to the most recent developments in AI research and practice: he’s sharp and bold in naming the concerns, but also able (as here) to show the ways in which AI platforms can be extremely helpful.

“It’s got nothing to do with Vorsprung durch Technik, y’know?”

Just back from an amazing weekend at my beloved Laity Lodge, where I got to hang out and kinda-collaborate with some astonishingly gifted people, including Dana Tanamachi, Uwade, and Jon Searle — plus my buddy Austin Kleon. Hearing Uwade sing live sent chills down my spine — you can get a sense of her amazing vocal presence by watching this. Goodness, being around people this gifted … well, it’s humbling. That’s a mild word for it.

So long (for now) to the canyon.