Continuing to experiment with shooting on 35mm film, this time Fujicolor 200. The process of experimentation could be very long….

Timothy B. Lee: “The vibe in the AI industry today feels a lot like the self-driving industry in 2018.” A compelling comparison.

If I need something that does have answers that can be definitely wrong in important ways, and where I’m not an expert in the subject, or don’t have all the underlying data memorised and would have to repeat all the work myself to check it, then today, I can’t use an LLM for that at all. […]

Of course, these models don’t do ‘right’. They are probabilistic, statistical systems that tell you what a good answer would probably look like. They are not deterministic systems that tell you what the answer is. They do not ‘know’ or ‘understand’ — they approximate. A ‘better’ model approximates more closely, and it may be dramatically better at one category of question than another (though we may not know why, or even understand what the categories are). But that still is not the same as providing a ‘correct’ answer.

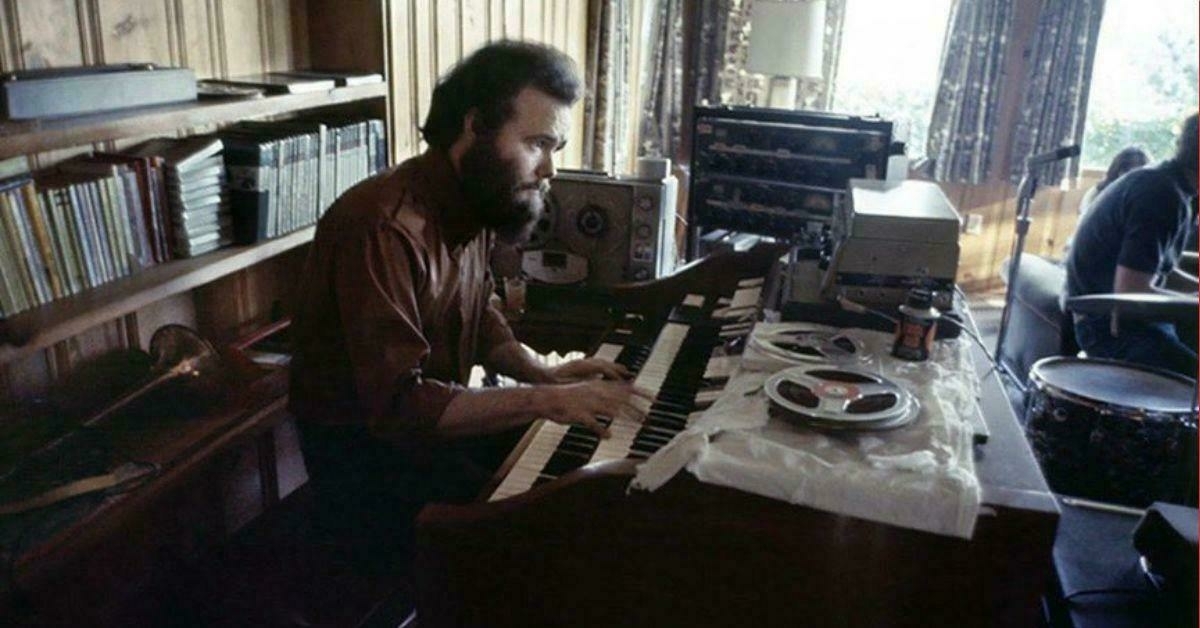

Some enterprising publisher needs to commission me to write a book about The Band.

Robert Christgau in the Village Voice, December 1969, on two albums released four days apart: “Abbey Road captivates me as might be expected, but The Band is even better, an A-plus record if I’ve ever rated one.” He’s right. Dammit, he’s right.

When we’re out for a walk, Angus frequently looks up at me as if to say, “Are you enjoying this as much as I am??” When I’m tired, I want to reply, “By the sound of it, no.” But he’s so adorable I just agree with his enthusiasm as best I can.

From a couple of years back, two quotations on slow reading.

Take fact checking out of that intimate, human setting, turn it into an industrial program of outsourcing, crowdsourcing, or automation, and it falls apart. It becomes a parody of itself. The desire to “scale” fact checking, to mechanize the arbitration of truth, is just another example of the tragic misunderstanding that lies at the core of Silicon Valley’s entire, grandiose attempt to remake society in its own image: that human relations get better as they get more efficient. A community, we seem fated to learn over and over again, is not a network.

UPDATE: A typically thoughtful note from Leah Libresco Sargeant prompts me to add that I think Carr’s general point here about scale is absolutely correct, but Community Notes just may be a step towards the re-humanizing of fact-checking. I’m writing an essay on some of these themes and in it will develop my thinking at greater length.

Charlie Stross, who before becoming a novelist was a pharmacist, has written part 1 of a guide to poisons and poisoning — but for novelists, not would-be murderers!

My friend and former colleague Ralph Wood has written a lovely tribute to his old teacher Norman Maclean — author of A River Runs Through It.

Seba Jun: one of one.

Currently listening: Nujabes, Spiritual State ♫

Two quotations on what exists. The twoquotes tag is a favorite one of mine.