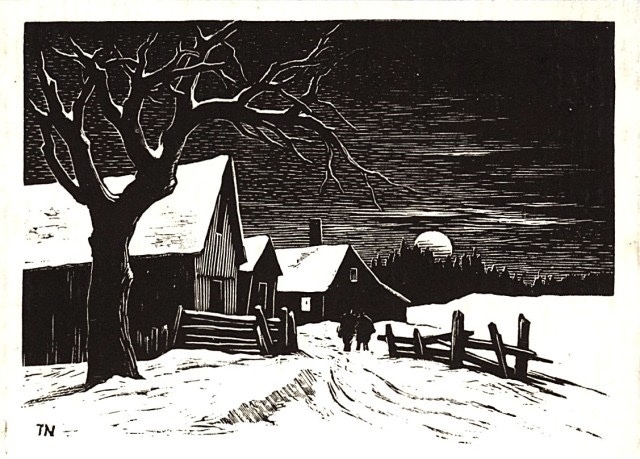

Thomas W. Nason, illustration for Donald Hall’s Here at Eagle Pond (1990).

Re-upping from a year ago today: Why I don’t keep track of how many books I read.

Do yourself a favor and listen to the incomparable Ella sing “What Are You Doing On New Year’s Eve?”

Martin Van Buren “proceeded swiftly from senator to secretary of state, vice president and president. And though he failed to win a second term, [James M. Bradley says, ‘He built and designed the party system that defined how politics was practiced and power wielded in the United States.’ We are living in the world Van Buren created.” Good to know whom to blame.

New entry in my series on family, about the poet Robert Hayden.

foggy, Christmassy, spooky

Damien Walter: “Just give Adam Roberts a Hugo already. It’s getting embarrassing! Like not giving Taylor Swift her Grammys.”

Mike Sacasas channeling Lewis Mumford: “Life cannot be delegated.”

Got to thinking English thoughts when I came across this photo, taken in 2011 on the way up Wansfell Pike. Larger version here.

On impulse, I made a list of places in England I’ve visited.

Thomas Traherne, Centuries of Meditations I.5:

I will not by the noise of bloody wars and the dethroning of kings advance you to glory: but by the gentle ways of peace and love. As a deep friendship meditates and intends the deepest designs for the advancement of its objects, so doth it shew itself in choosing the sweetest and most delightful methods, whereby not to weary but please the person it desireth to advance. Where Love administers physic, its tenderness is expressed in balms and cordials. It hateth corrosives, and is rich in its administrations. Even so, God designing to show His Love in exalting you hath chosen the ways of ease and repose by which you should ascend. And I after His similitude will lead you into paths plain and familiar, where all envy, rapine, bloodshed, complaint and malice shall be far removed; and nothing appear but contentment and thanksgiving. Yet shall the end be so glorious that angels durst not hope for so great a one till they had seen it.

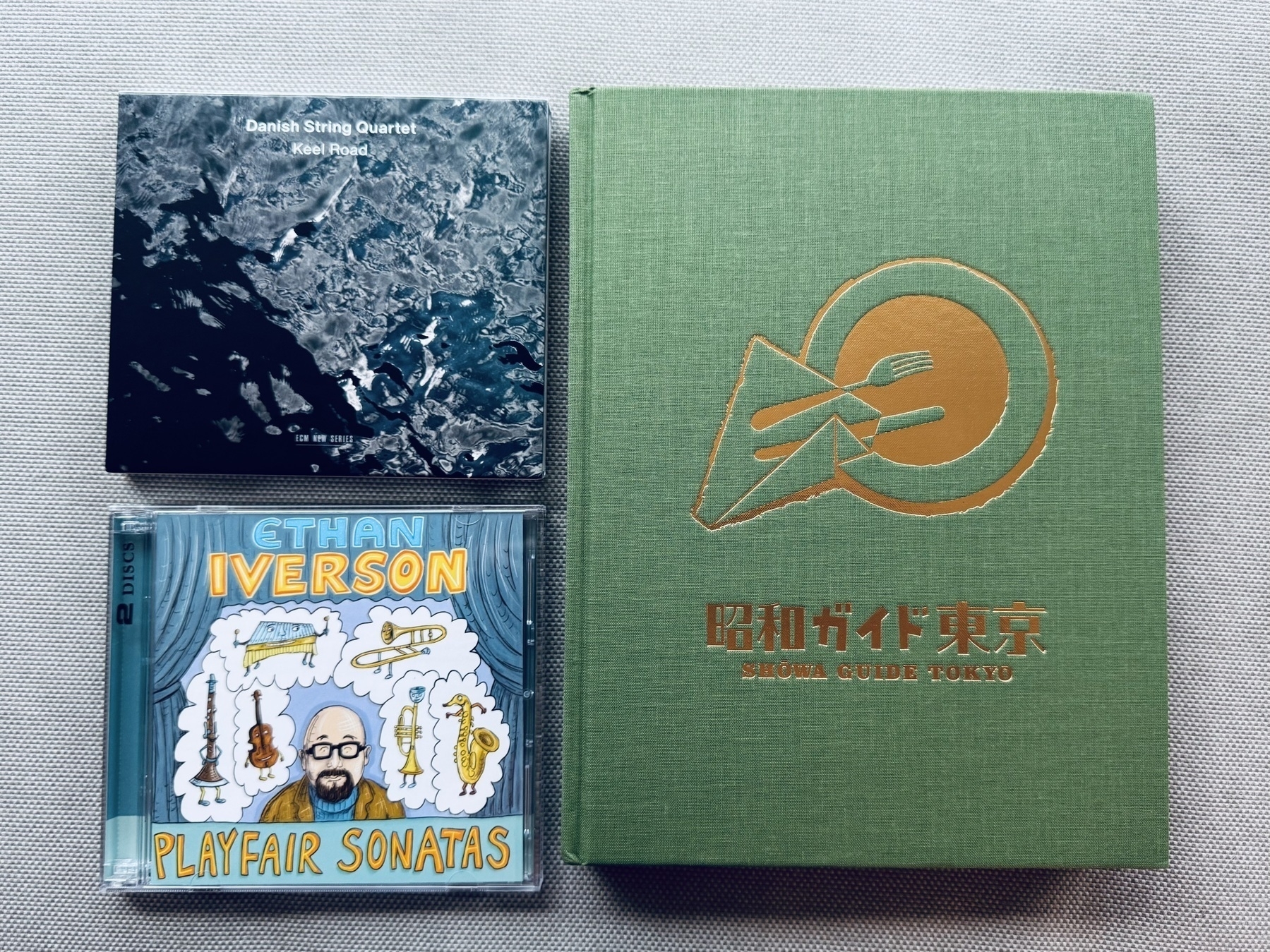

Christmas presents!

“Wild Mountain Thyme” is one of the world’s loveliest songs, and thousands of singers have recorded it, so you might think that it would be impossible to decide whose version is best. But no, it’s an easy call: Sandy Denny.

This is better.

Angus did not like wearing his Christmas bandanna as a babushka. We immediately removed it.