Freddie: “If I had to have American policy be determined by polling the userbase of X or the userbase of BlueSky, I would choose the latter and sigh as they passed a law that ordered my own personal execution on public safety grounds. They’d probably do it by forcing me to drink fair trade cyanide through a paper straw.”

Picasso, “Leaping Bulls”

I’m probably going to regret this, but I’ve enabled crossposting from micro.blog — Home of the Truly Cool — to Bluesky. I won’t be be otherwise present. Advertisements for myself will begin immediately.

The Economist: “New work led by Roza Kamiloglu, a psychologist at the Free University of Amsterdam, provides evidence that there are just two primary types of laughter: one generated when people find something funny and one that can be induced only through the physical act of tickling.” I’m laughing about this, but only because I’m currently being tickled.

My colleague Philip Jenkins settles a few persistent myths about the Council of Nicaea. It’s one of those events about which people always feel free to tell Big Lies.

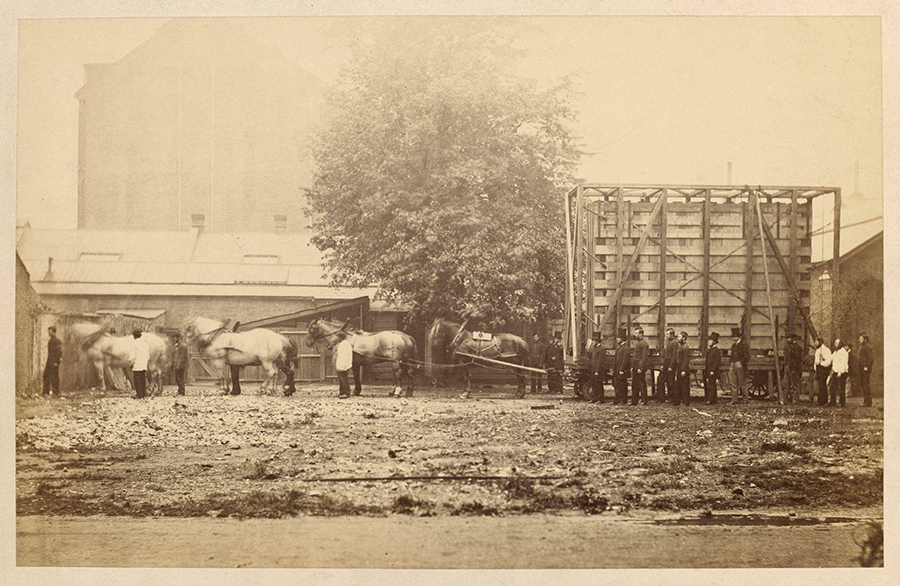

Charles Thurston Thompson, Side view of packing case and horse-drawn ‘van’ for transport of Raphael Cartoons from Hampton Court to South Kensington Museum, 1865. The South Kensington Museum is now of course the V&A.

Currently listening: Bill Evans, The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings, 1961 (Live) ♫. Of the many glorious performances on this record, perhaps the most glorious is “I Loves You, Porgy.” Heartbreakingly beautiful … and all the time the tiny audience is chattering away in the background. I don’t blame them — there was no way for them to know that one of the definitive recordings in jazz history was being made right before them — but I just want to teleport into the room to scream “SHUT UUUUUUPPPP.”

After you listen to “I Loves You, Porgy” a few times, go back one more time and listen just to the bassist, Scott LaFaro. He was a great genius, and would die in a car accident eleven days later, at the age of twenty-five.

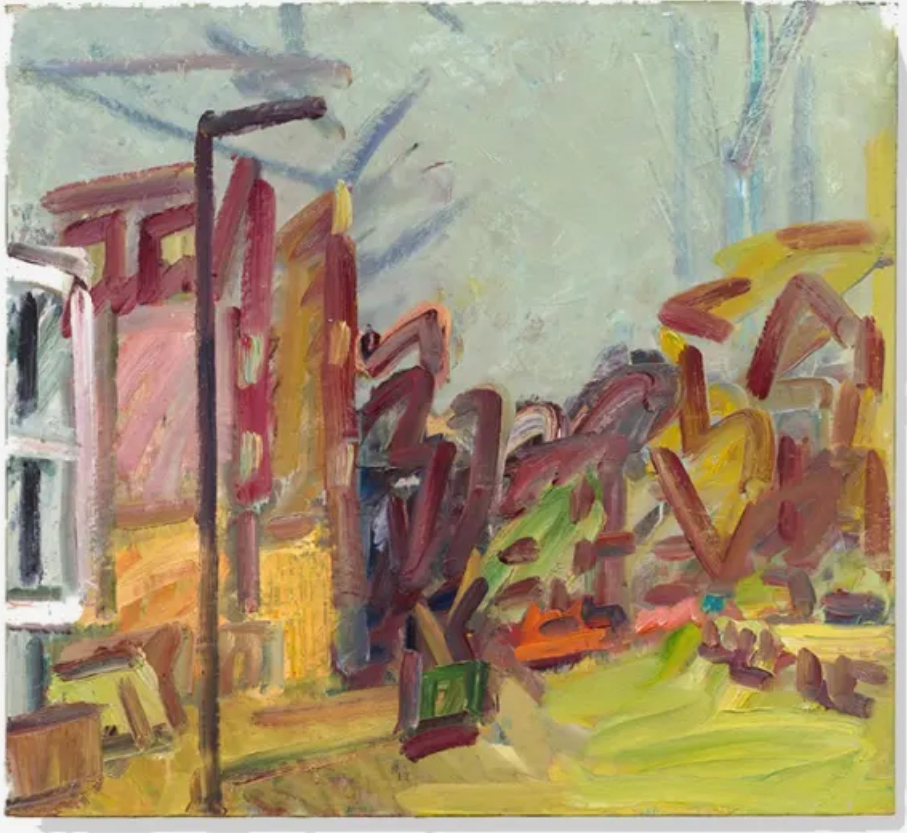

Frank Auerbach — who died last week — “Albert Street II”, 2010

On a foggy morning, this streetlight in my neighborhood offers a gentle alien-invasion vibe.

Weather forecasts in central Texas:

- Five days out: 90% chance of rain

- Four days out: 80% chance of rain

- Three days out: 60% chance of rain

- Two days out: 40% chance of rain

- One day out: 20% chance of rain

On the day: No rain

A brilliant essay on orphans and robots from Adam Roberts. An idea-filled essay that’s generative of further ideas.

I am somewhat compensated for the non-arrival of Fall by continuing blooms (thanks to the gardening work of my beloved).

Barney Ronay on the likelihood of Saudi Arabia hosting the World Cup: “This will stand as surely the most wretched, bloody, damaging act in the history of global organised sport. If not causing death were your starting point, your one non-negotiable, Saudi Arabia wouldn’t even be on the table. And yet Infantino appears to have actively sought this outcome, aligning his Fifa with the world’s most ruthlessly ambitious carbon power; and as a consequence taking choices that will, it can be assumed, cause demonstrable death and suffering.”