Via this post from Sara Hendren — AKA @ablerism — I see that I need to read Dougald Hine. One sentence from Hine’s book sums up so much that is essential: “The entitlements of late modernity are not compatible with the realities of life on a finite planet and they do not even make us happy.”

So here I am praising David Brooks for … thinking some of the things I think, I guess. But I can’t help it if he and I are both right!

The response by Gemma M. (whom I don’t know) at my most recent BMAC post is fascinating to me, and truly moving.

Mark 7:34. I should get points for biblical literacy instead of being rejected.

dozing

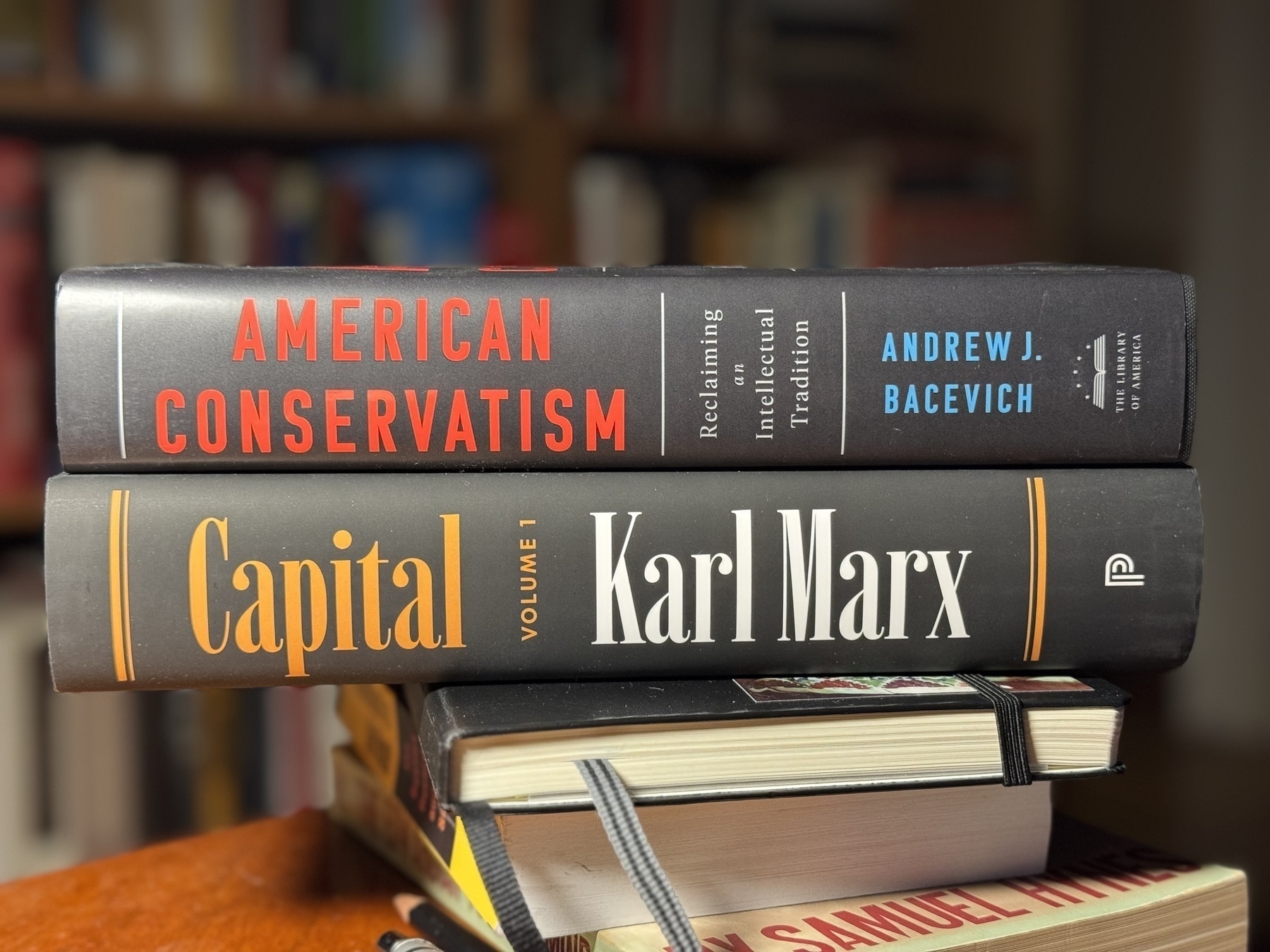

Perfect pairing in the mail today.

Here in Waco, from 5pm this afternoon to 9am tomorrow morning the temperature will drop fifty degrees. Fifty.

Kieran Healy on his Modern Plain Text Computing class:

To help address these challenges, modern computing platforms provide us with a suite of powerful, modular, specialized tools and techniques. The bad news is that they are not magic; they cannot do our thinking for us. The good news is that they are by now very old and very stable. Most of them are developed in the open. Many are supported by helpful communities. Almost all are available for free. Nearly without exception, they tend to work through the medium of explicit instructions written out in plain text. In other words they work by having you write some “code”, in the broadest sense. People who do research involving structured data of any kind should become familiar with these tools. Lack of familiarly with the basics encourages bad habits and unhealthy attitudes among the informed and uninformed alike, ranging from misplaced impatience to creeping despair.

Man, I’d love to take that class.

I was curious about students’ causal arguments about this sudden eclipse of pleasure reading — again, the They who killed their love of reading. Why did it happen? The most common argument from them was that being made to analyze what they read had killed their enjoyment, not only of the analyzed, assigned texts but of texts in general. Now it’s possible that this is true, or true for some people, but because I am a teacher and because it’s my job to encourage people to think, I simply can’t accept it. It is baldly anti-intellectual and it is wildly counter to my experience and my observations of the world. I simply do not believe that thinking about things is in itself toxic to our enjoyment of those things — if that were true, there would be no sports radio. I absolutely believe that thinking about things in the wrong way — for example, in a deadening or loveless way — or under unnecessary pressure is toxic to our enjoyment of them, but that’s different. With almost anything but reading, deeper understanding leads to deeper pleasure — this is true of sex, football, food, the behavior of pets, everything else in the world. Why should reading be the one exception?