I wrote about anarchism as a spiritual discipline.

Thesis: the first album — as a coherent work of art, not merely a collection of songs — was Frank Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours (1955); the last one was Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea (1998).

The thing I love about sports is the way it can bring the world’s top political powers together.

USA men’s 🏀, gold medal game, shooting in the last 3 minutes:

- Curry made 3

- Durant made 2 FT

- Curry made 3

- Curry made 3

- Curry made 3

- Booker made 2

Sixteen points, and they didn’t miss.

So Emma Hayes leads the (formerly quite broken) USWNT to a gold medal and all the Brit footy commentators can talk about is how she got her tactics all wrong. ⚽️

This new post by Chris Arnade — faithful chronicler of forgotten America — is harrowing. And I come away from it just praying that something good will happen for the young woman he met named Caroline.

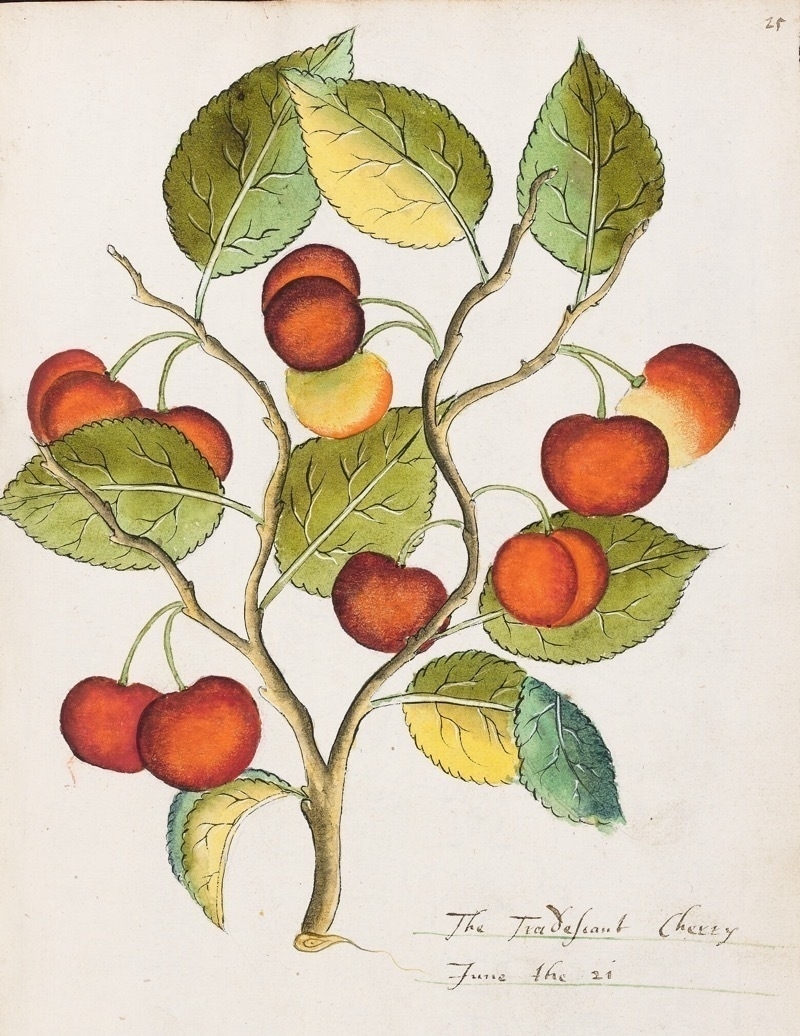

Tradescant’s Orchard (Bodleian Library)

What a cool idea from Leah Libresco Sargeant: “I’d like to write a Chrome extension that delays opening certain webpages (like Twitter) and shows an interstitial page for 30 seconds or so, with a randomly chosen prayer intention from a list I can edit.”

I am aware that microtonal jazz-blues might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but I love the new Alec Goldfarb record. ♫

I have no idea why, but I have received dramatically more fan mail — that is, messages of enthusiastic gratitude — about my essay on “the mythical method” than I am used to. (Usually people only write to tell me what I’m wrong about.)

I wrote about colonialist owls.

update on domain issues

I still don’t have my domain issues ironed out, but (a) I am beginning to have some hope of keeping the old blog up — even though I know that it’s the hope that kills you; and (b) I have imported my entire WordPress blog to micro.blog, so, while I don’t have the old tags, you can search for anything you’re looking for. You can also, of course, find the whole blog via the Wayback Machine.

While I’m trying to sort all this out, I’m going to delete my “changes ahead” post and resume new posting there, at least for now.

I love how for the Times southern Ohio and western Nebraska are both (waves hand) “the Midwest.” How can two politicians offer such radically different “views” of (waves hand) the Midwest?

There are several annoying errors in this piece, but let me single out one: the claim that Tolkien wasn’t invited to Lewis’s wedding. No one was invited to a marriage that took place in Joy Davidman's hospital room because it was feared that she was near death. Lewis's brother Warnie and a nurse served as witnesses.

Part of the CBS Television Studio in New York (1978) from the Eyes of a Generation Viewseum