Craig Mod on Tokyo: “The saving grace is that Tokyo has a distinct advantage over other cities in that it extends, effectively, infinitely in most directions that aren’t the ocean (and even there, we’ve added quite a bit in the last hundred years). And is ultra-connected by perfectly-functioning public transportation. So you’re seeing what used to be more centralized ‘cultural texture’ move east and west — out to Kuramae, Kiyosumishirakawa, Gakugeidaigaku, Itabashi, and more; not unlike the Brooklyn migrations from a Duane-Reade-and-Citibank-infested Manhattan in the naughts and 2010s. But for me, one of the great joys is wandering the central neighborhoods of the city, those abutting the ‘Hills’ and mega-developments, finding those rare streets still replete with homes and shops of a city that once was. Finding one of those four-hundred baths. There are still common relationships to luxuriate in, even as the towers loom.”

My multi- and super-talented friend Catherine Woodiwiss, who’s always doing something fascinating, has just launched a newsletter.

One of my retirement dreams is to get skilled enough at web design to do with my site something half as cool as what Roger Strunk has done with his.

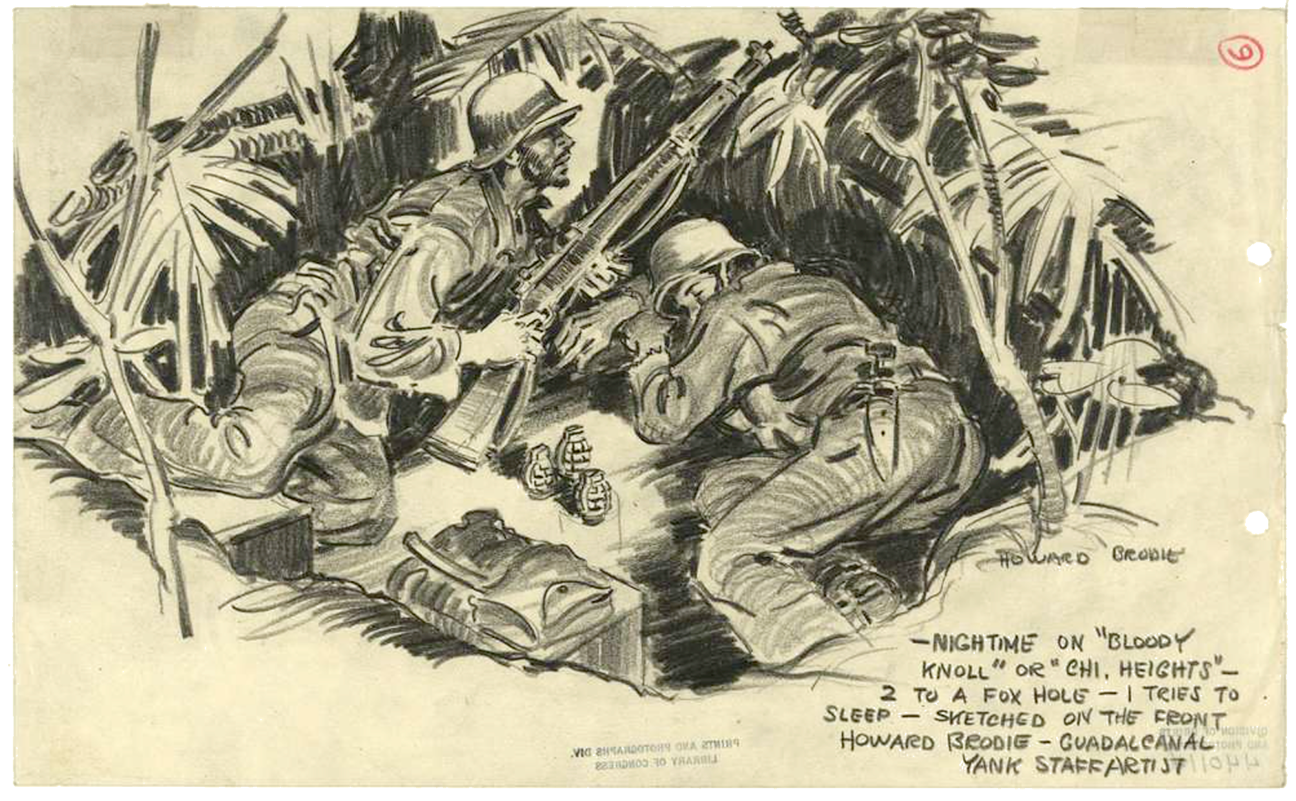

My series of posts on the battle for Guadalcanal, and artistic representations thereof, has reached its fourth installment.

Guadalcanal: 4

As I noted in my previous post, the peculiar nature of the Guadalcanal campaign creates a kind of narrative frame — the arrival by sea, the fighting, the departure by sea — that any account of the campaign is bound by. This traversing of emptiness surrounding a tragic agon.

I think it was Jakob Burckhardt, in his famous book The Greeks and Greek Civilization, who first identified the agon — the contest or competition — as “the paramount feature of life” in ancient Greek civilization.

Thus after the decline of heroic kingship all higher life among the Greeks, active as well as spiritual, took on the character of the agon. Here excellence (arete) and natural superiority were displayed, and victory in the agon, that is noble victory without enmity, appears to have been the ancient expression of the peaceful victory of an individual. Many different aspects of life came to bear the marks of this form of competitiveness. We see it in the conversations and round-songs of the guests in the symposium, in philosophy and legal procedure, down to cock- and quail-fighting or the gargantuan feats of eating. In Aristophanes' Knights, the behaviour of the Paphlagonian and the sausage seller still retains the exact form of an agon, and the same is true in Frogs of the contest between Aeschylus and Euripides in Hades, with its ceremonial preliminaries. The way that life on all levels was influenced by the agon and by gymnastics is most clearly illustrated by Herodotus' account of the wooing of Agariste (VI.126). Cleisthenes of Sicyon announced at the Olympic games, where he had just won the victory in the four-horse chariot race, that he invited applicants for his daughter's hand. The wooing, itself an agon, is a kind of mirror image of the mythical wooing of Hippodamia, daughter of Oenomaus. Thirteen suitors came forward, all personally outstanding and of high birth; two were from southern Italy, one Epidamnian, one Aetolian, one Argive, two Arcadians, one from Elis, two Athenians and one each from Euboea, Thessaly and Molossus [in Epirus). Cleisthenes had a stadium and a palaestra prepared for them, kept them with him for a year and tested their courage, temperament, upbringing and character; he accompanied the suitors to the gymnasium and observed their behaviour at feasts.

(This book, assembled from Burckhardt’s lectures, was published after his death in 1897 and against his will. The early modern period was his area of specialization, and he did not think himself qualified to publish a book on the Ancient Greek world. But the idea got around, to Burckhardt’s annoyance, thanks to a former colleague: “The mistaken belief that I was to publish a history of Greek culture derives from a work of the unfortunate Professor Nietzsche, who now lives in a lunatic asylum. He mistook a lecture course that I used often to give for a book.”)

The agon is a kind of domestication and confinement of the battle encounter, of the confrontation of people who are determined to kill one another. The ancestor of the agon, and in a way its heart and soul, is the confrontation of Hector and Achilles in the 22nd book of the Iliad. Perhaps the most important thing to be said about the agon as depicted by Homer that it is only secondarily a competition with your enemy, with the Other; it is primarily a contest with yourself.

Homer makes this abundantly clear through one distinctive element of the encounter between Hector and Achilles. Recall that Achilles has returned because of his grief and guilt at allowing his dearest friend Patroclus to enter the battle wearing his armor. Hector has taken that armor from the dead body of Patroclus and is now wearing it. Meanwhile, Achilles has had new armor made for him by Hephaestus, including a great shield. In my introduction to Auden’s book The Shield of Achilles I describe what Hephaestus has made:

In Homer's poem, the shield is complexly figured, but at the heart of its depiction is a simple contrast. First, there is a world of peace, in which the arts (both the artes mechanicae and the artes liberales) may be cultivated: dancers and acrobats and musicians appear there, well-cared-for fields of crops, vineyards full of ripe grapes, and herds of animals domesticated for human use. Evil things happen in this world: two lions kill a bull; a man has killed another man. But herdsmen watch over their cattle to limit the ravages of wild beasts; and in the city of peace judges determine a penalty for murder, a penalty that the angry family of the slain man agree to. Such agreements are what make a city peaceful. But none of these arts and agreements obtain in the second city, the city of war; there, all is sacrificed to the cultivation of a single “art”: that of killing.

All through the Iliad Hector is depicted as a reluctant warrior. In Book VI he tells his beloved wife Andromache that he has learned to fight in the front ranks of the Trojans — he does it because he must, to protect the city he loves; but fighting does not come naturally to him, as it does to Achilles, who doesn’t know what to do with himself when he’s not fighting.

So when these two men met on the field of battle, what do they see? Hector sees the world he loves, the world of peace and art and hot baths, with war only an interruption of that better human story; and Achilles sees his own armor, the armor of the ultimate warrior. Each confronts himself, and this is the essential character of the agon.

In Malick’s The Thin Red Line, this is what battle does to the men: it forces each of them to confront himself. Again and again that confrontation is revelatory.

Harry R. Lewis: “Today’s AI-giddy techno-optimists and techno-pessimists might heed Henri Poincaré’s caution: ‘The question is not, “What is the answer?” The question is, “What is the question?"‘The humanities have pressed the great questions on every new generation. That is how they differ from the sciences, a literary scholar once explained to me; humanists don’t solve problems, they cherish and nurture them, preparing us and our children and grandchildren to confront them as people will for as long as the human condition persists. Our hope for the beneficial development of AI rests on the survival of humanistic learning.” (Harry Lewis is a computer scientist.)

Rachel Haywire: “The fediverse is boring! The trade-off for the freedom that the fediverse offers comes at the cost of excitement and engagement. Its decentralized nature has resulted in fragmented and disjointed communities, lacking the cohesion necessary for meaningful connections. The promise of escaping the echo chambers of centralized platforms has led to a barren environment plagued by inactivity and disinterest.” This, though perhaps overstated, points to a genuine problem.

A fantastic post by Sara Hendren — AKA @ablerism — on how universities ought to, but do not, signal their various social obligations and purposes through architectural diversity. The build world as a guide and frame for the complex experiences of young people.

This meditation by Ryan Burge on the closing of the church where he has been a pastor for many years is deeply sad. The poem for such moments is Frost’s “The Oven Bird.”

A while back I noted that some enthusiastic recent writing about the great Guy Davenport doesn’t really give you a sense of how uniquely strange it is to read him. Well, that deficiency is remedied by Mark Clemens in this exceptionally acute essay.

Barath Raghavan and Bruce Schneier:

The [CrowdStrike] catastrophe is yet another reminder of how brittle global internet infrastructure is. […] This brittleness is a result of market incentives. In enterprise computing — as opposed to personal computing — a company that provides computing infrastructure to enterprise networks is incentivized to be as integral as possible, to have as deep access into their customers’ networks as possible, and to run as leanly as possible.

Redundancies are unprofitable. Being slow and careful is unprofitable. Being less embedded in and less essential and having less access to the customers’ networks and machines is unprofitable — at least in the short term, by which these companies are measured. This is true for companies like CrowdStrike. It’s also true for CrowdStrike’s customers, who also didn’t have resilience, redundancy, or backup systems in place for failures such as this because they are also an expense that affects short-term profitability.

A reminder that presentism is perhaps an even bigger threat to our economic infrastructure than it is to our common culture.

pre-dawn

Guadalcanal: 3

The above is a drawing by Howard Brodie, an artist James Jones much admired.

The distinctive way the Allied commanders organized the campaign for Guadalcanal, coupled with certain features intrinsic to island warfare, shaped the structure of Jones’s The Thin Red Line. Here’s how the novel begins:

The two transports had sneaked up from the south in the first graying flush of dawn, their cumbersome mass cutting smoothly through the water whose still greater mass bore them silently, themselves as gray as the dawn which camouflaged them. Now, in the fresh early morning of a lovely tropic day they lay quietly at anchor in the channel, nearer to the one island than to the other which was only a cloud on the horizon. To their crews, this was a routine mission and one they knew well: that of delivering fresh reinforcement troops. But to the men who comprised the cargo of infantry this trip was neither routine nor known and was composed of a mixture of dense anxiety and tense excitement.

In this respect the story of these soldiers resembles the Normandy invasion: it begins with a sea crossing. You must get on a ship and traverse the ocean to get to the place where you will fight.

But the attackers on D-Day in Normandy didn’t finish their war that way, not collectively anyway. Of course, some of them returned the way they came; but many others pushed deeper and deeper into Europe, and when they were done, made their way back home by airplane, or in transport ships with highly miscellaneous passengers.

What’s distinctive about The Thin Red Line is that C-for-Charlie Company travels to the island on a ship and then step onto the beach from landing craft — and then when it is relieved it returns in precisely the way it came. (“Ahead of them the LCIs waited to take them aboard, and slowly they began to file into them to be taken out to climb the cargo nets up into the big ships.”) It’s like entering and leaving a gladiatorial arena, except that there are these long sea journeys, crossings of empty liminal space, a space that radically separates what happens on the island from everything else in life, before and after. It’s more like Purgatory, then, than an arena — except for those who die. For them, I suppose, it’s Hell.

That some of them die while others survive means that C-for-Charlie Company is not precisely the same on its arrival and its departure. But the way Jones tells his story, the deaths are not presented as the deaths of individual whole persons but rather as the loss of appendages. Jones repeatedly speaks of the Company as a single entity: “But before that happened the whole of C-for-Charlie had gotten blind, crazy drunk in a wild mass bacchanalian orgy which lasted twenty-eight hours and used up all the available whiskey….” “Meanwhile back at the bivouac C-for-Charlie was still trying desperately to solve its liquor shortage.” When the Company comes across a dead soldier: “D Company had found him while pursuing the Japanese patrol and had placed him on the ledge behind C-for-Charlie for safekeeping at a time when C-for-Charlie was too engrossed in its firing to notice….” When stretcher-bearers take the dead man away: “C-for-Charlie had watched all this action wide-eyed and with sheepish faces.” One entity that happens to have many faces.

All of this is deeply relevant to the film Terrence Malick would make from James Jones’s novel.

Google’s search deal with Reddit is yet another of the thousand ways in which the open web is closing.