I’m reading Robert Richardson’s biography of William James and I’m struggling: almost every male person in it is named either William or Henry.

Here is the second in a series of posts about the battle for Guadalcanal and some artistic responses to it.

Guadalcanal: 2

How vividly did the Guadalcanal campaign impress itself on the American imagination? Well, this movie was released around nine months after the last Japanese soldiers were driven from the island.

But all the media were moving at fast pace in those days. In propaganda, as in so many other things — internment of undesirables, terror-bombing of civilians —, the Nazis established the standard that their enemies emulated. The Wehrmacht invaded Poland on 1 September 1939 and by November the official documentary film, Sieg in Polen, was being shown in New York City, where it was seen by, among many others, W. H. Auden and Thomas Merton. (This was the subject of one of my first scholarly articles.) Likewise, in June of 1942 John Ford carried a camera with him to record what would become known as the Battle of Midway, and the edited footage appeared as a short film in September, with a score by Alfred Newman and narration by Henry Fonda.

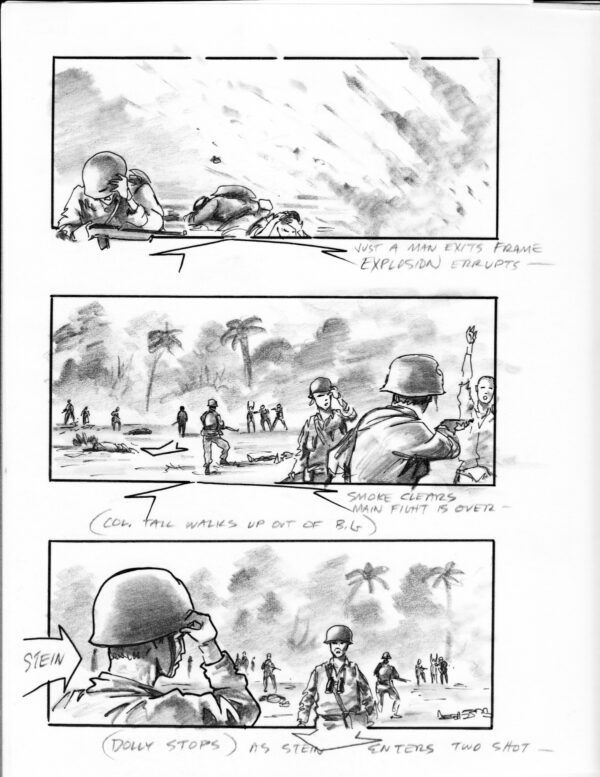

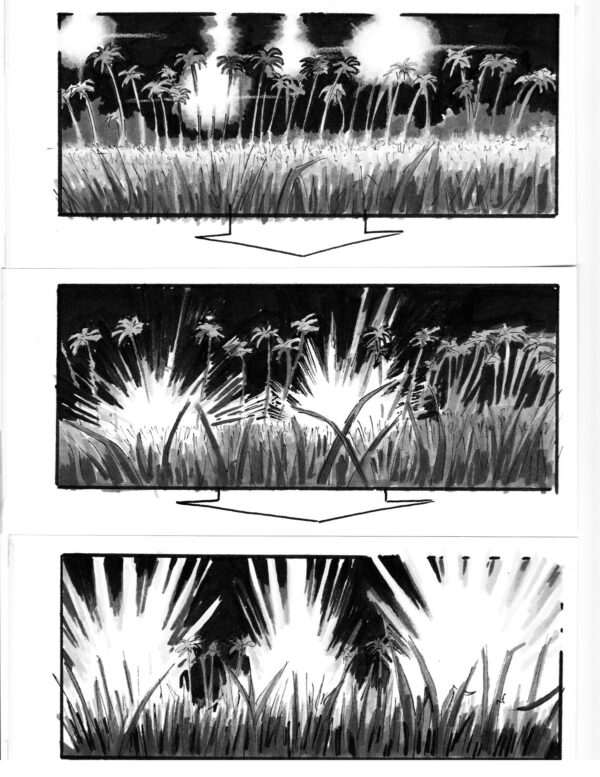

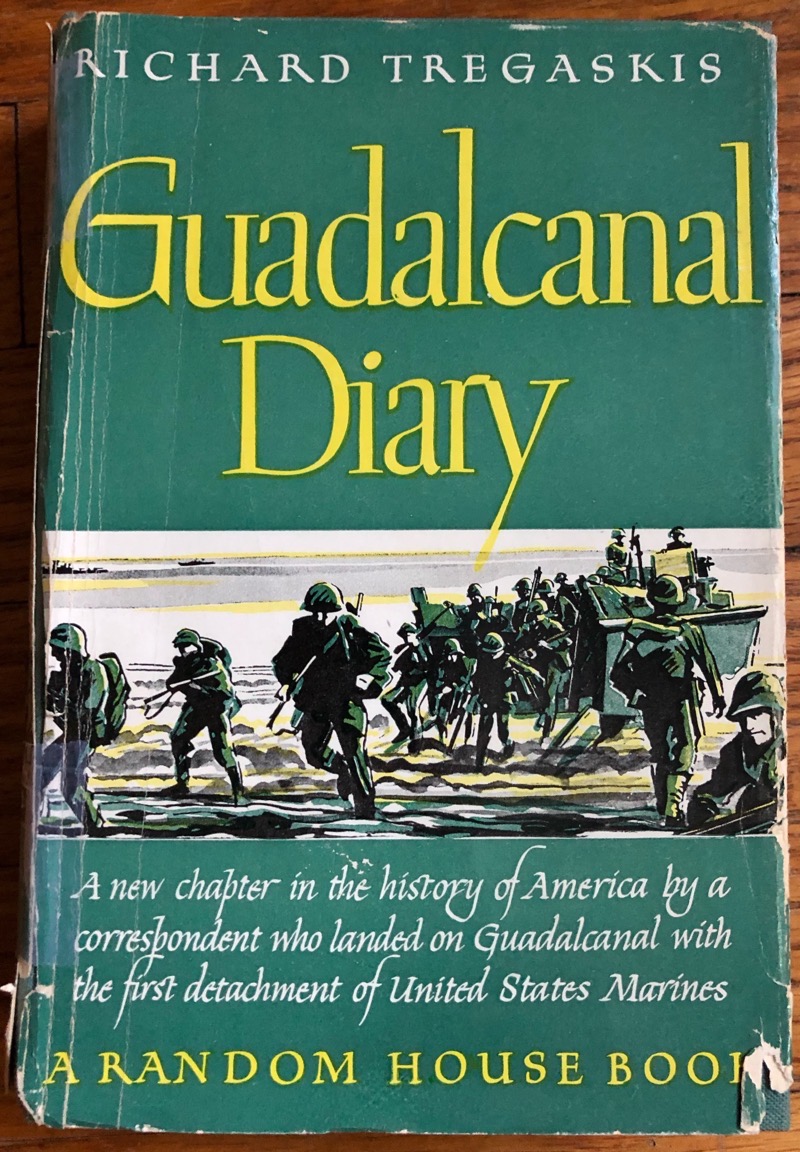

And when the Guadalcanal campaign began shortly afterward, a young journalist for Life magazine named John Hersey accompanied the American troops, as did Richard Tregaskis, a reporter for the International News Service. Both of them sent dispatches from the front which were published immediately, and then quickly turned them into books: Hersey’s Into the Valley and Tregaskis’s Guadalcanal Diary were both published on the first day of 1943. The latter was, in a vague sort of way, the basis for the movie.

Tregaskis’s book — and this is a point to which I will return in later installments of this series — is bookended, as any account of an island battle is likely to be, by sea journeys: an arrival and a departure. Landing craft deliver soldiers to the island; the soldiers enter the hell of battle; eventually those who survive, relieved by new soldiers, return to the landing craft and are conveyed to a place of rest. (The First Marine Division, who had begun the invasion in August, were relieved in early December and taken to Melbourne, where they were greeted, quite properly, as great heroes.) There’s something intrinsically ritualistic, almost mythic, about this pattern.

But there’s also, in the context, something consoling about it.

The movie of Guadalcanal Diary maintains this structure: the first twenty minutes show the Marines on ship headed towards battle, demonstrating camaraderie among regions and races: a very young black soldier has a speaking part! One of the chief characters is a Mexican-American! (One of the few times in his career that Anthony Quinn played his own ethnicity.) They grow slightly more anxious, though, before landing on … an undefended beach. (This is one of the better effects of the movie — the anticlimax of arriving for battle and finding no one to fight.)

Eventually they encounter the enemy first in small numbers — the initial battle set-piece enacts an event Tregaskis made famous, the Goettge patrol — and then in larger numbers, until we approach a final battle, preceded by prayers, confessions of dis-ease, and letters home to families. In that battle one of the leading characters — it had to be Alvarez, didn’t it? — is killed, and then the Marines are relieved. At the end they’re marching towards the ships that will take them away, and the narrator — a version of Tregaskis — is pleased to say that they’ll receive “a well-earned rest, the job superbly done. The Army is coming in to take over. Into their hands we commit the job, with full confidence in their ability to perform it.”

And that’s the consoling message, for soldiers but perhaps especially for the families of soldiers: the fighting will be tough, but it won’t last too long, and almost everyone will survive. No need to get too anxious.

When the movie came out, James Agee wrote that it “is unusually serious, simple, and honest, as far as it goes; but it would be a shame and worse if those who made or will see it got the idea that it is a remotely adequate image of the first months on that island.… I think it is to be rather respected, and recommended, but with very qualified enthusiasm.” In that note Agee said that he hoped to write at greater length about the move, but, alas, it appears that he did not. I would very much have enjoyed hearing what his reservations were. Mine, as the above summary suggests, are significant. I thought it clichéd and profoundly unrealistic in every respect; though perhaps in comparison to still-more-jingoistic endeavors it was not.

(Also: the movie has quite a number of Asian or Asian-American actors playing Japanese soldiers — not one of whom is named. I would give quite a lot to know who those men were, how they were cast, and what they thought about the whole business.)

Now, back to real life: one of those Army men who relieved the Marines on Guadalcanal was James Jones, and he wrote about his experience in the novel The Thin Red Line (1962). Soon after that book’s publication, Jones wrote an essay for the Saturday Evening Post called “Phony War Films.” He explains how, after his return from the war — he was discharged from the Army in 1944 because of a bad ankle, an experience that he gives to Corporal Fife in The Thin Red Line — he found himself laughing incredulously at war movies. Sometimes he even walked out on them. Then, almost two decades later and in preparation for writing his article, he watched a bunch of more recent films about the war he had fought in. His verdict:

When I finished, I was not only almost cross-eyed from watching film, near death from explosive sound effects, I was more depressed with the essential adolescence of America (maybe I should say of the race) then I have perhaps ever been. If our war films are indication of our social maturity in an age when we have the capacity of destroying ourselves, there is little hope for us….

Now, why is this? Why, after so much soul-searching by Americans, so many advances in so many other fields during the past twenty years, have war films remained at the same, essentially adolescent level as the war films of 1943?

Jones's basic answer is that the film studios are giving people what they want.

By the way, that essay — which as far as I can discover is not available online — is reprinted in the booklet that accompanies the magnificent Criterion Collection edition of Terrence Malick’s film The Thin Red Line. And yes, that’s where this series is headed … but we still have business with James Jones and his novel.

rainy morning in the canyon

For the Princeton University Press Ideas blog, I wrote about my critical edition of Auden’s collection The Shield of Achilles.

Guadalcanal: 1

From December of 1941 through the middle of the next year, the Japanese Army and Navy enjoyed an unbroken series of victories that carried them to the doorstep of Australia. The conquest of Australia was indeed their next major endeavor. They planned to begin it by taking Port Moresby, on the southern coast of New Guinea, from which the whole of northern and eastern Australia would be easily reachable.

Their first setback came in early June 1942 at the Battle of Midway, which John Keegan called “the most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare.” It was that; but the Japanese forces still held all the territory they had conquered in the previous seven months. What Midway did, more than anything else, was to demonstrate with an absolute conclusiveness that Japan was not invincible — indeed was quite vulnerable.

Two steps followed for the Allied forces. (By Allied forces I mean Americans and Australians; the division of labor had left the British to focus on China, India, and Burma.) One was to prevent the taking of Port Moresby; the second was to begin reclaiming territory that had great strategic importance. From the Allied perspective, a key piece of land was Guadalcanal, the largest of the Solomon Islands, east of New Guinea. The Japanese, having occupied the island in May, had immediately begun constructing an airfield from which they would be able to send aircraft to disrupt, or prevent altogether, shipping between the United States and Australia. Since the Japanese already had a major air and sea base at Rabual on New Britain, a functioning airfield on Guadalcanal would establish dominance over a large chunk of the south Pacific.

It was vital, the Allied commanders believed, to drive the Japanese off Guadalcanal, complete the airfield for their own use, and thereby (a) protect shipping lanes and (b) establish a staging ground for an assault on Rabual and New Britain more generally. Guadalcanal was, then, the first island in the island-hopping strategy that would eventually lead the Allied forces to Japan.

When Allied troops landed on Guadalcanal in the early morning of 7 August, the Japanese soldiers and workers at the airfield abandoned it immediately, having been taken wholly by surprise. Indeed, the Japanese command had not expected an Allied counterattack of this size for some time. One of the first consequences of the Allied landing on Guadalcanal was the shifting of Japanese troops from the assault on Port Moresby — where Australian forces had been holding off Japanese forces in terrible conditions and with extraordinary determination — to the Solomons. So Port Moresby was safe, at least for a while.

The Japanese were determined to show the Allies that the re-taking of territory was impossible; the Allies were equally determined to make their first major counter-attack a successful one. The consequences of failure on Guadalcanal were, for both sides, too dire even to contemplate.

In the battle for the island — a battle which did not definitively end until February of 1943 — three points were established that dictated the remainder of the war. First: that the resources, in personnel and equipment, that the Allies could bring to bear on the conflict were unprecedentedly enormous. Second: that, Japanese assumptions to the contrary, American soldiers would fight bravely and indeed relentlessly. Third: that Japanese soldiers would fight to the death — death by the enemy’s hand or by their own or by starvation — rather than be taken prisoner. These were the lessons of Guadalcanal and they were learned with great pain on all sides. The Japanese came to call Guadalcanal “Starvation Island” and “Death Island”; to the Americans, William Manchester says, it was “that fucking island,” and the fighting there “worse than Stalingrad” — though (or therefore) to this day the insignia of the First Marine Division bears the single word “Guadalcanal.”

Something about the War in the Pacific was, and still is, summed up in that one campaign for that one not-obviously-important island. It has resonated in memories and minds through the decades. It seems to have something it wants to tell us about war.

Sources:

- Anthony Beevor, The Second World War

- James Jones, The Thin Red Line

- John Keegan, The Second World War

- William Manchester, Goodbye, Darkness

- Ian W. Toll, The Pacific War Trilogy (reading in progress)

victimology

I’ve been meaning for some time to write a brief post about Freddie deBoer’s case for forcing mentally ill people into treatment — or rather, about one element of the story. And then today I see a new post by Freddie on this review of this book by Jonathan Rosen, and that got the wheels turning.

None of this is within my own area of expertise or experience. I have no authority here. I just want to call attention to one point. Rosen’s book is about his friend Michael Laudor, who in 1998 murdered his fiancée Caroline Costello during a psychotic episode. I have not read the book, but when I heard about it, I think originally from Freddie’s Substack, I immediately remembered a book that made a great impact on me when I read it forty years ago: The Killing of Bonnie Garland, by an eminent psychiatrist named Willard Gaylin. I was reminded of it because of of one small detail linking the two situations: Yale University, which Laudor, Costello, and Rosen all attended in the early 1980s, as did Bonnie Garland and the man who killed her, Richard Herrin, in the mid-1970s.

Here’s how Gaylin describes the origins of his book:

Richard Herrin, then twenty-three, had killed his college sweetheart, Bonnie Garland. He had hammered her to death in her sleep in her parents' home. This was the tragic culmination of a three-year romance. Richard Herrin, a poor Mexican-American boy, had been a junior at Yale University when he met seventeen-year-old freshman Bonnie Garland. Bonnie was a child of affluence. Daughter of Joan and Paul Garland, she had spent much of her childhood in Brazil, where her father was establishing a very successful international law practice. She had attended the fashionable Madeira School and went on to Yale, her father's alma mater.

Bonnie Garland was an unlikely victim of a killing. But then again, Richard Herrin was an unlikely killer. And the course of events following the killing was strange and unpredictable. Within two months of killing Bonnie, Richard Herrin was not in prison but attending classes at the State University of New York in Albany, working in a religious bookshop there, and being unstintingly supported both emotionally and financially by a Catholic community.

I am not a devotee of crime news; I rarely read it in the papers. But there was something unusually bizarre about this crime and its sequelae. I remembered one brief phrase from the reporting; Richard had been quoted as saying within hours of the killing, “Her head broke open like a watermelon.” Who speaks in those terms? What kind of human being even thinks that way? One might expect a general revulsion, a turning away from the vile and indecent. But many did not turn away. The Catholic community at Yale University, where both Richard and his victim, Bonnie Garland, had been students, mobilized by Ashbel (“A.T.”) T. Wall, a former roommate of Richard's and a member of an affluent and socially prominent New England family, along with Father Peter Fagan and Sister Ramona Pena, Catholic associate chaplains at Yale, began a crusade of compassion for Richard. The Garlands — her room in their house still soiled with their daughter's blood and brain tissue — started a counter-crusade. This would eventually include hiring a private eye, appearing on a TV talk show, and interviews in such gossip sheets as the Star and National Enquirer.

Gaylin followed the case closely and came to focus on one question: In the aftermath of this killing, why were there so many more tears for Richard Herrin than for the young woman he killed? And this is his answer:

Our mechanisms of identification and empathy are central to our concepts of what is good and what is right. From the day of the killing, Richard attracted a host of concerned and compassionate defenders. When one person kills another, there is immediate revulsion at the nature of the crime. But in a time so short as to seem indecent to the members of the personal family, the dead person ceases to exist as an identifiable figure. To those individuals in the community of good will and empathy, warmth and compassion, only one of the key actors in the drama remains with whom to commiserate and that is always the criminal. The dead person ceases to be a part of everyday reality, ceases to exist. She is only a figure in a historic event. We inevitably turn away from the past, toward the ongoing reality. And the ongoing reality is the criminal; trapped, anxious, now helpless, isolated, often badgered and bewildered.

Gaylin attended Richard Herrin’s trial and noticed that the prosecuting attorneys did nothing to remind the jury of the former existence of Bonnie Garland. They did not even introduce a photograph of her. Meanwhile, the defense suggested that Bonnie — who had dated Richard for the better part of three years but had grown less interested in him — had not been sufficiently attentive to his emotional needs, had not really understood how difficult life was for him, a kid from the barrio, at Yale. Richard’s attorney did not accuse her of anything; as Gaylin notes, “the slight suggestion of her complicity and insensitivity was sufficient.” But gradually the defense was able to shift the jury’s attention in such a way as to suggest that she was really the one on trial. “She was diminished, and, in suggesting that she was somewhat responsible for her own fate, made an accomplice to her own killing. She was on trial, and was given no voice, no presence. No real attempt was made by the prosecution to bring her to life.”

So the jury’s sympathies, like those of the Catholic community at Yale, shifted towards Richard. Later, after the trial, the villains in the story become Bonnie’s parents, rich white people who in their arrogance and entitlement wouldn’t forgive the troubled boy from the barrio.

François Truffaut was the first person to note that the key scene in Psycho comes when Norman Bates cleans up the shower where Marion Crane has been murdered. For 45 minutes we, the audience, have been learning to sympathize with this imperfect young woman, obviously the protagonist of the story, and now she’s dead. What do we do? Truffaut says that we transfer our sympathies to Norman Bates, and the lengthy clean-up scene — which also involves the disposal of her body, which we never see again — gives us the chance to do that.

But we don’t know that Norman Bates is Marion’s murderer. Wouldn’t things be different if we did know that he’s a killer? Gaylin’s argument is: Not necessarily. Not if the victim is dead and gone, absent, invisible. In the absence of the victim, Gaylin says, the murderer “usurps the compassion that is justly his victim's due. He will steal his victim's moral constituency along with her life.” The living sympathize with the living, not with the dead. And — this is in some ways Gaylin’s key concern — his own profession, psychiatry, does more than any other force in American life to facilitate the transfer of compassion from the murdered to the murderer.

All this says nothing about the case of Michael Laudor and Caroline Costello — I know little about that and, again, haven’t read Rosen’s book. But I was greatly taken, all those years ago, with Gaylin’s explanation of how we transfer our sympathies from the dead to the living, from any absent victim to any present offender — whom, thanks to the mechanical workings of our criminal-justice and mental-health systems, we can easily perceive as “the real victim here.” It’s worth noting, perhaps, that when I first posted this reflection I read through it and noticed that the first sentence of this paragraph referred to “the case of Michael Laudor” — I had left out the name of the woman he murdered.

the rise of detective fiction

In The Long Week-End, their entertaining, sardonic, and often insightful social history of England between the two world wars, Robert Graves and Alan Hodge assert that in the years immediately following the Great War, “Detective-novel writing was not yet an industry; Sherlock Holmes stood alone.” (That comment, like this post, refers only to the British situation; the American situation was quite different.)

This is perhaps a bit of an exaggeration. Historians like Graves and Hodge tend to ignore the Sexton Blake stories, presumably on the grounds that they were mass-produced, by multiple authors who worked from simplistic templates, and were aimed primarily at younger audiences. But they were extraordinarily popular and it seems that almost everyone read at least some of them. (When Dorothy L. Sayers was ill at school — the Godolphin School in Salisbury — she wrote to her parents to ask them to send her some Sexton Blakes.) And then, on what one presumes G&H would have thought a higher level of literary ambition, there were the Father Brown stories — but Chesterton, having written a pile of them between 1910 and 1914, did not write another until 1923.

Meanwhile, the Sherlock Holmes wagon continued to roll, though with a pause (as many things paused) in the war years, during which Conan Doyle published only one Holmes story, “His Last Bow,” which was an exercise in patriotism and, moreover, a spy story rather than a tale of detection. But Conan Doyle would, with great reluctance and annoyance, resume Dr. Watson’s accounts of Holmes’s adventures in 1921.

Two other data points should be introduced here. First, the publication in 1913 of what would become one of the most influential novels of detection ever written, E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case. And second, the 1910 trial and conviction of Dr. Crippen, which renewed interest in what we now call True Crime.

If you look at these matters from the perspective of the year 1914, here’s what I think you see:

- the Sexton Blake stories rolling ever onward, but according to a fixed formula;

- the Holmes stories continuing but more slowly, and at a far lower standard than Conan Doyle had established in the 1880s and 1890s;

- an interesting experiment in a type of detective radically different than Holmes (Father Brown), which appeared to be complete;

- another interesting experiment, this one a playful questioning of the plot conventions of the tale of detection (Trent’s Last Case);

- a renewal of interest in True Crime.

So the future of tales of detection did not appear to be bright, and there was no reason to think that it would become a central genre of fiction.

Then the War came, and such topics were placed, not on the back burner but off the stove altogether. It was difficult, or embarrassing, or just plain shameful to think about a domestic murder or a crime of passion or a killing for money when the greatest slaughter in the history of humanity was ongoing. One could easily imagine that period marking the end of the detective story as a popular genre of fiction.

When the War ended, though, it became possible and indeed desirable to think about such matters again. It was presumably a kind of relief to be able, once more, to consider malice and death on a human scale — death as a tragedy and a misery but not an unimaginably vast horror. So Conan Doyle resumed his Holmes stories with “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone” in 1921, and Chesterton his tales of Father Brown with (I think) “The Resurrection of Father Brown” in 1923. But even more to the point:

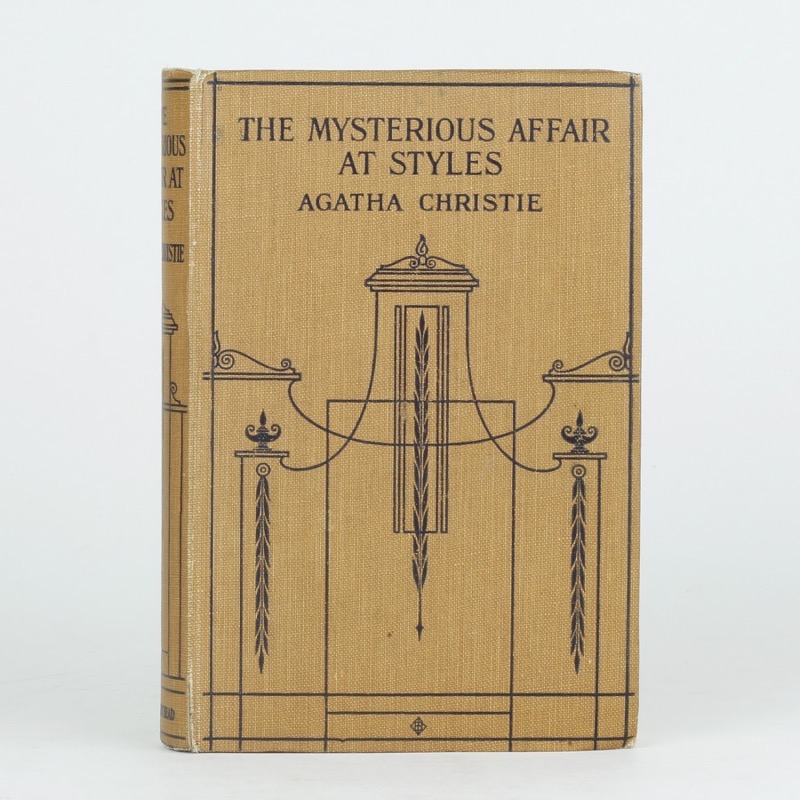

- Agatha Christie published her first mystery novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, in 1920;

- Freeman Wills Crofts published his first, and by far most influential, mystery novel, The Cask, also in 1920;

- Dorothy L. Sayers wrote her first detective novel, Whose Body?, in 1921, though it was not published until 1923;

- The Thompson-Bywaters trial was held in 1922, and after the execution of the convicted murderers in January of 1923, their story became a matter of extravagant public fascination for a very long time.

And so we were off to the races. The Golden Age of detective fiction — influenced at least as much by True Crime as by previous stories and novels — had begun. And I cannot help thinking that it was shaped, then and later, by the great shadow of Death hanging over Europe in the aftermath of the Great War.

On renewing the art of biological taxonomy: “With genetic sequences, we can now identify the fundamental building blocks of life, but we need to be able to interpret genetic data in a way that humans can understand and use. That’s taxonomy’s job. And if we want to save what’s left of the vast diversity of life on Earth, we’ll have to reinvest in this science. How we delineate between species determines what we choose to save.”

Anthony Lane on a new book about SF movies released in the summer of 1982:

Such is Nashawaty’s command of superlatives that he merits a sci-fi yarn of his own. “The Optimizer,” perhaps. Or “The Hyphenator.” Thus, “Star Wars” is lauded as “a true once-in-a-generation pop-culture juggernaut,” while the triumph of “The Wrath of Khan” was to turn “a cash-grab sequel into a franchise-resuscitating classic.” Far from scorning this excitable tic, I find it both judicious and contagious; the book’s parsing of “Halloween” as “a babysitter-in-peril slashterpiece” is hard to quibble with, and I wonder what other paragons of the medium would profit from so crisp a paraphrase. Ingmar Bergman’s “Cries and Whispers”? A crimson-tinged, don’t-hold-back Scandi cancerthon. Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc”? A chat-free high-stakes teen roast. Once you slip into the habit, you can’t stop.

I’m gonna have some fun with this game.