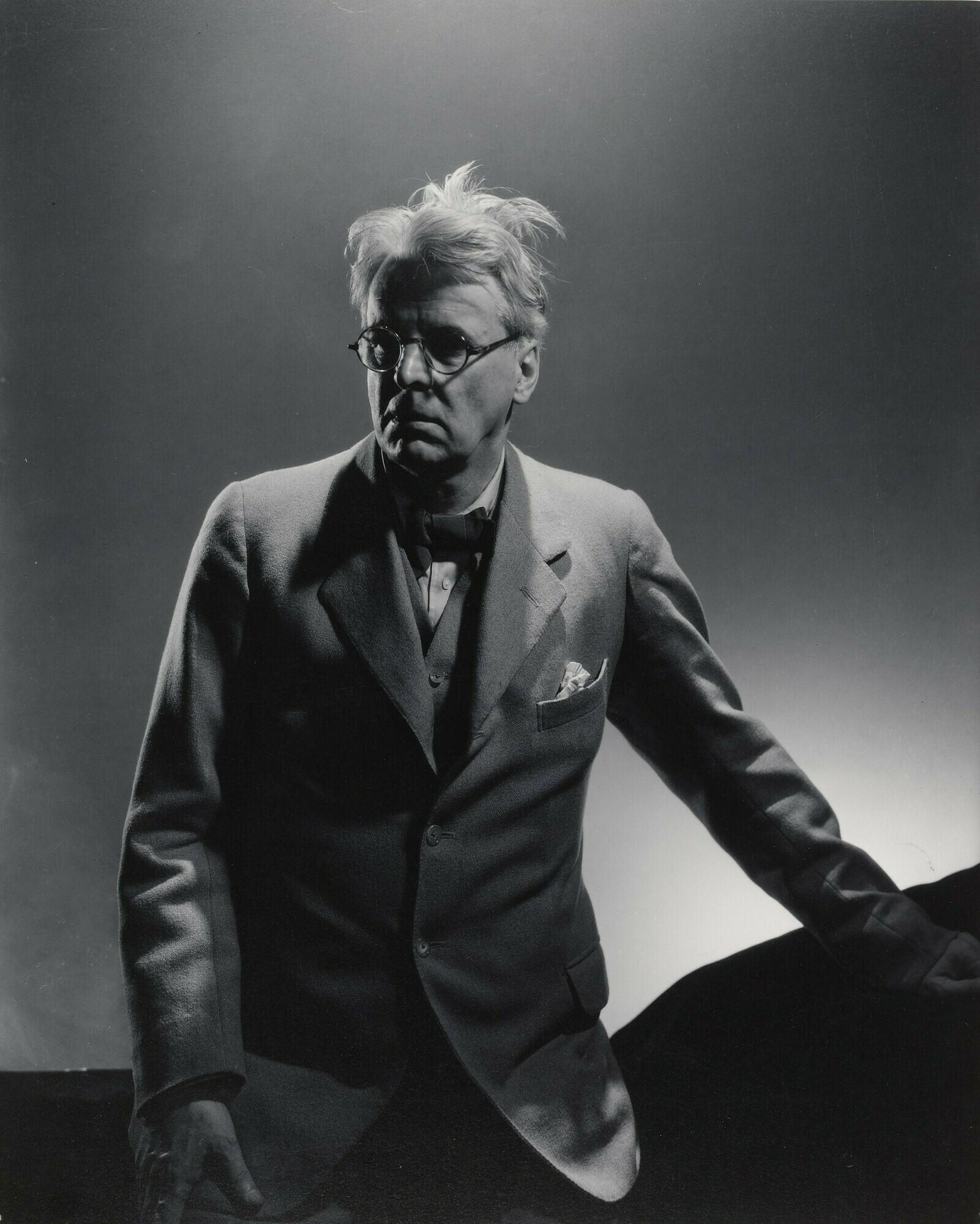

For literary figures, Steichen would stage his portraits formally, but not theatrically. Here’s W. B. Yeats.

Or this one of Gloria Swanson. (“Mr. de Mille … I’m ready for my closeup!")

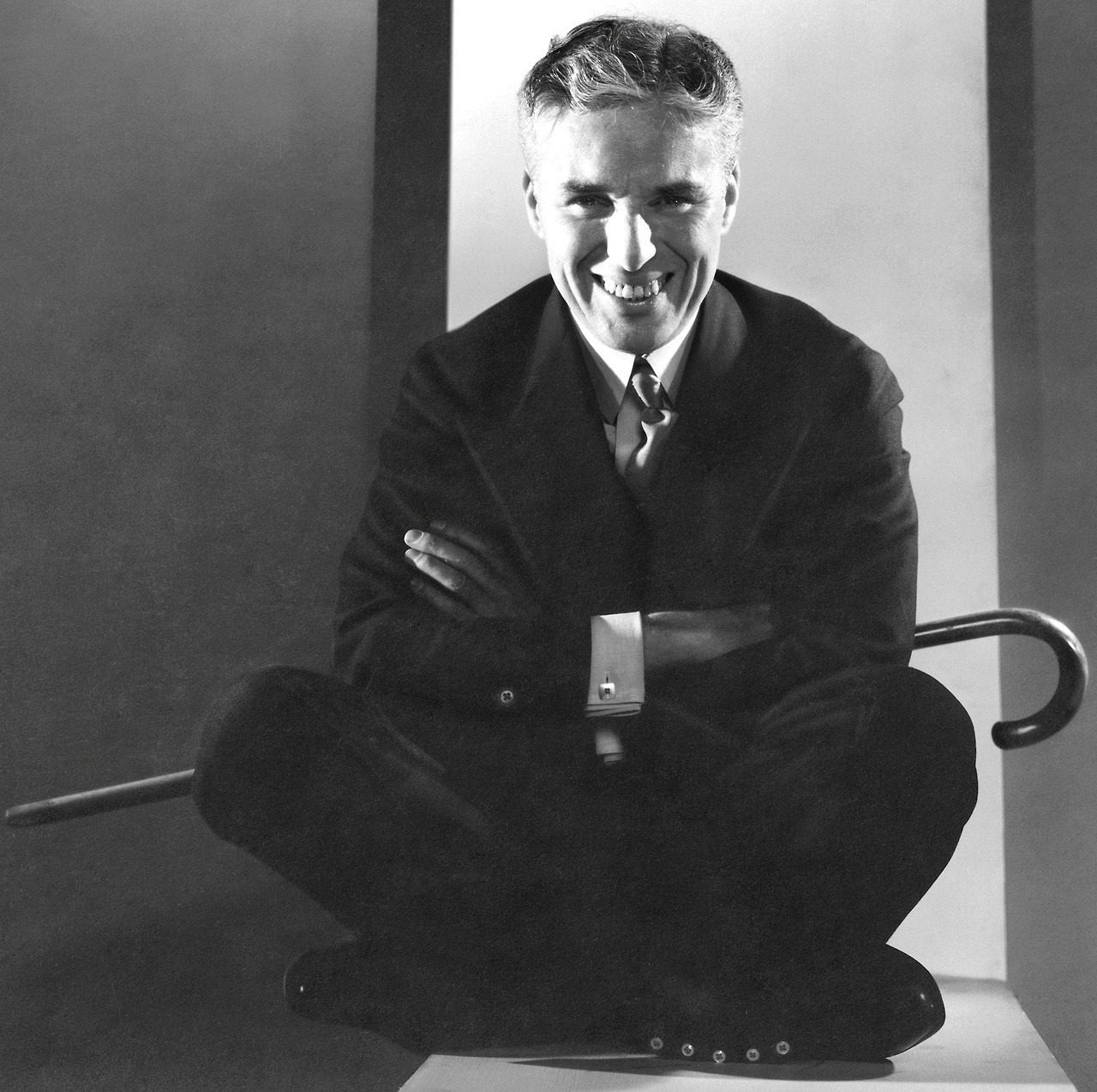

Or this one of Charlie Chaplin.

But Steichen is most famous for his portraits, some of which are theatrically staged, almost a tableau vivant, like this one of Fred Astaire.

If I had to name the greatest photographer of all time, I’d say Henri Cartier-Bresson. But close behind would be Edward Steichen, who is, I believe, the most versatile photographer of all time. One of his most famous photos is this one, of the Flatiron Building in Manhattan.

I updated my post on England’s non-football. ⚽️

All praise to Sir Ollie of Torquay!! 🏴⚽️

Here in the second half against 🇳🇱, 🏴 has gone back to non-football. The announcers are flipping through their in-case-of-nothingness talking points. ⚽️

In the Dictionary of National Biography, Davidson is identified as “Church of England clergyman and circus performer.” The account of his adventures in Ronald Blythe’s The Age of Illusion is brilliant.

Sometimes you come across people whose stories you think simply must be made up — but aren’t. Ladies and gentlemen, please meet Harold Davidson, the Rector of Stiffkey.

This young fella struggled a bit last year, but our rainy late spring has done wonders for him.

un-football

Even England, this England’s version of hole-in-the-head football will give you dramatic interventions, trapped energy, last-minute overhead kicks. Somehow France entered this game as the only team at the Euros not to have registered an assist. Before this semi-final they played five games during which nobody on either team had scored from open play.

This isn’t “anti-football”. It’s un-football, non-football. It’s time being killed, athletically, talent reduced to furniture. Watching France is like watching someone do accounts, brilliantly, like watching a team of your favourite elite entertainers very diligently assembling a shed, and then realising towards the end that actually, they really are just assembling a shed.

Watching France and England in this tournament first bored me, then frustrated me, then made me actually angry. Both sides played the whole tournament as though they had been told that excessive movement would deplete their oxygen supplies and cause them to faint. They just stood and passed the ball around until someone on the other side took the ball away from them, at which point they reluctantly trotted back to defend.

Bukayo Saka has been almost the only English player to get exercise, and exercise produced a goal. For France, Mbappe occasionally tried, but when he did he got closed down by three or four defenders because they weren’t worried about what anyone else in the France jersey would do. It was dire.

The most frustrating thing is: There’s nothing that can be done when teams choose to play this way. It’s not against the rules, and you can’t change the rules in any way that would fix the problem, unless it’s possible to give players electrical shocks when they stand in one place for too long.

But you have to ask yourself: Why do they choose to play this way? I think pressure is a relatively small part of it. The real issue is that these players play far too many games. If you want to have good Euros and World Cups, then you have to eliminate some of the competitions, both domestic and trans-domestic.

Spain has been very good and sometimes fun in this tournament; the Dutch have had their moments; Switzerland, Austria, and Georgia were all great. So it’s not all bad news. But far too much of Euro 2024 has indeed been bad news, because it’s been played largely by exhausted players.

UPDATE 2024-07-10: Today against the Netherlands England played much more positively for a half, after which they looked worn-out. It took Southgate a loooong time to make the necessary substitutions, but when he did — wow: two subs, Palmer and Watkins, combining for the winning goal.

So: the Three Lions in the final! I am excited! Do I repent of my criticisms of Southgate? I do not. I have said all along that he (a) sets up his defense excellently, (b) allows or encourages too much caution in attack, and (c) is too slow to make changes. I still think all that. Because England defend so well, they are always in a position in which one goal can make the difference for them. But crossing your fingers and hoping for a late moment of brilliance isn’t a good strategy, even if you happen to get that moment of brilliance three matches in a row: Bellingham, 95th minute; Saka, 80th minute; Watkins, 90th minute. You’re trusting your luck too much, and even when luck shows up, there are better ways to play the game.

But I will say this: the first half today, in which England were so much more dynamic and endeavoring and footbally than they have been all tournament, suggests that Southgate knows that he’s been too cautious. The problem is that the players simply couldn’t sustain that level of energy. So here’s my prediction for the final: If Southgate makes two or more subs before the hour mark, England will win … or at least take it to penalties. (Kinds hedging my bets there.)

pointillisme

Jim Groom: “The archaeology of knowledge on the web over the last 25 years is dominated by the gravitational darkness of broken link errors created by individuals and organizations that fail to understand, or care about, the cultural importance a link might represent.” Too true.

When I first read Robin Sloan’s Moonbound, in galleys, I wasn’t, for several reasons, in the right frame of mind to receive it. I should have waited, but I was thinking, But this is Robin’s new book! He put a lot into this! Duh. I should have read at whim! Now I have really read it, and I love it.

Moonbound revisited

A while back I said that I had read Robin Sloan’s new novel Moonbound and hoped to read it again. Wrong! I had not genuinely read it. Now I have, and I love this book.

Several decades ago, the semiotician A. J. Greimas claimed that all stories are comprised of six actants, in three pairs:

- Subject/Object

- Sender/Receiver

- Helper/Opponent

Moonbound is a book that readily lends itself to this analysis.

We (you and I and the other humans on this planet) are the Anth — the Middle Anth, as it happens. Our descendants will do some amazing things but tragedy will eventually befall them. But, anticipating their downfall, they prepare a message, in the form of a girl in cryogenic sleep, for those who will occupy the Earth after them. (Sender/Receiver.)

The girl eventually joins forces with a boy, Ariel, the protagonist of our story, who wants to know how to combat the dragons who live on the moon and have cut earth off from the rest of the cosmos. (These dragons are made of information. It’s complicated.) The dragons have made Earth the Silent Planet, as it were, and Ariel wants to end that silence, that isolation. In this quest he is forever pursued by an angry wizard, but also regularly finds help from unexpected friends. (Helper/Opponent.)

It is through the mediation of some of those friends, a college of scholars, that Ariel encounters the most important Helper of all, who makes for him the one thing he needs to deal with the dragons. (Subject/Object.)

See? It’s brilliant. And the pattern is reinforced by constant references to another story, the one on which this one seems to be modeled: the matter of Arthur. But then, it’s a lot like many other stories as well. For instance, at one point our small hero is led through the wilderness by a rough customer he meets in a tavern, one who is called by a nickname beginning with S, and who provides him with a means of swift escape from his pursuers. It’s true that this fellow is a trash-picker rather than the descendent of kings, and that he’s called Scrounger rather than Strider, but the commonalities are strong and that’s what matters, isn’t it?

Or is it?

What makes a story matter to us? Does interest lie in the ways it resembles other stories, as Greimas’s scheme seems to suggest, or in the ways it differs from them?

At one point, early in Moonbound, when Ariel is still living in the village of Sauvage, at a desperate moment he runs towards a prominent feature of the village: a sword plunged into a stone. His companion, the narrator of this book (again: it’s complicated), thinks, “I knew this story! The words inscribed on the sword read — The boy hurried past. Ignored it completely.” He retrieves a very different sword that, as it turns out, is much more helpful to him — though this greatly angers the wizard who has plotted Ariel’s life. (One man’s Helper is another man’s Opponent.)

Having gone off-script, Ariel is confronted by the enraged wizard:

“The stone is my design. As is the village. As are you.” The directness of his speech made the boy's blood sizzle. “Yet you did not pull the sword. Why?”

“I found another,” Ariel said simply.

The wizard frowned. “Another sword ought not to have sufficed. The pattern is burned into your cells. Don't you feel it? Or is my design so poor?”

“Of course I feel it,” Ariel said quietly. First, triumph and terror; now, dread and calm. “But there are other designs, too.”

And maybe not just designs. If you were to ask me why Ariel found the other sword, the sword that wrecked the plans of the manipulative, controlling wizard, I’d say that he just got lucky.

Luck, this tale suggests, is a big factor in human affairs. From a conversation that happens later in the book, between Scrounger and Durga, the girl awakened from sleep, “the last daughter of the Anth”:

“The way I’ve heard it, the Anth destroyed themselves,” said Scrounger. “Maybe you’re right, and maybe your future yanked you straight into disaster. Maybe there’s a lesson there.”

”The end of the Anth wasn’t hubris,” Durga said. “I know that’s an easy story to tell, but it’s not true. We were beyond that.”

”A lot of hubris, saying you’re beyond hubris.”

”Yet I am saying it.”

”All right, I’ll allow it wasn’t hubris. What was it, then? What doomed your cause?”

”Bad luck,” Durga said simply. “There is such a thing, in history, as miserable bad luck.”

So, to sum up, what makes a story go off-piste? Luck, bad or good. Luck makes for stories rather than Story. Luck is the presiding spirit of the Garden of Forking Paths. Where Luck is present, you can’t map the scene with Greimas’s three pair of actants — that only gets you the X, Y, and Z axes. And as one of the characters — well, kind of a character: it’s complicated — explains to us, only a massive multidimensionality is genuinely adequate to the world.

Perhaps most important: Luck defeats the would-be Controllers, the ones who would dictate every step in everyone’s story — or maybe even bring stories to an end.

Well, probably. This too could be complicated.

- Let us grant, per argumentum, that Ariel wasn’t destined to find the sword he needed, or to meet the Helpers he needed to find. There’s no wise elder to tell Ariel, “You were meant to find that sword, and not by the wizard. And that may be an encouraging thought.”

- But Ariel, when we first meet him, says, “I know I am meant for something important. I can feel it. I have always felt it.”

- But the wizard programmed him to think this way: “The pattern is burned into your cells.”

- But the feeling persists in Ariel even after he liberates himself from the wizard’s tyranny. And if he is lucky, then his luck is extraordinary.

I am not sure that there is an answer to this conundrum, but we may find a way of negotiating it by reflecting on what Robin calls “Gibson-Faulkner Theory.” (The name is explained in this interview.) In the novel we merely learn that the “central premise of Gibson-Faulkner Theory” is: “The present is a function of the future, not the past.” As Durga explains,

“What I mean is — we have minds! We dream, and we plan, and then we take action. For that reason, our present is a function of the future we imagine. It is forged in response to vision. If we lack vision — well, then the ghosts will play, and that is our own fault. You can believe it or not. I know it is true, because I was born in San Francisco, the city the future reached back and made, because it was going to be needed.”

Now, I could (and probably will, in another post) argue with this — and as one of the progenitors of Gibson-Faulkner theory, I think I have a right to say that Durga’s articulation contains too much Gibson and not enough Faulkner. But the point is a powerful one. We act towards the future we have envisioned. And “Where there is no vision, the people perish” (Proverbs 29:18).

We love the old stories — we love stories that do what we expect them to do, what we know in advance they will do. But we also love it when they surprise us. Repeatedly in Moonbound we are told that “the great question of the Anth” is: “What happens next?” And we only ask that question when a story is surprising us, or when we hope it will.

We need themes, and we need variations on themes. And Moonbound provides both, and provides them delightfully. What a cool book. Hey Robin: More, please. I want to know what happens next.

I’ve been reading David Hume’s massive History of England, and here’s my first blog post on it.

the arc of Hume's history

I’ve been reading David Hume’s massive and magnificent History of England, and it’s generally fascinating — though there are, it must be said, extended passages in which he’s just dutifully relating what his researches have been able to discover about events which are not as well-attested as he would like. At the end of Volume II, when he has completed his narration of the Wars of the Roses with his account of the life and death of Richard III, he heaves a great sigh of relief:

Thus have we pursued the history of England through a series of many barbarous ages; till we have at last reached the dawn of civility and sciences, and have the prospect, both of greater certainty in our historical narrations, and of being able to present to the reader a spectacle more worthy of his attention.

That is, he’s about to enter the era in which increased political and social order (“civility”) and the invention and adoption of the printing press (“sciences”) yield far greater documentation of events.

In a famous essay, Arnaldo Momogliano argued that Gibbon, in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, sought to unite two kinds of historiography that previously had been quite distinct: the antiquarian history of les erudits and the philosophical history of writers like Voltaire. Gibbon was a great fellow for archives and inscriptions and ruins, but he was also determined to tell a story that enlightened and instructed. Hume — writing roughly a generation before Gibbon: the History of England was published between 1754 and 1762, while the Decline and Fall appeared between 1776 and 1789 — is very much the philosophical historian. His virtues, in his own estimation, are those of critical judgment rather than antiquarian assiduity. When he has more documentation, documentation that needs to be sifted and assessed with a shrewdly philosophic eye, his distinctive excellences come into play.

In one important sense his orientation is almost identical to that of Gibbon. Gibbon, famously, begins his history thus:

In the second century of the Christian era, the empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of mankind. The frontiers of that extensive monarchy were guarded by ancient renown and disciplined valour. The gentle, but powerful, influence of laws and manners had gradually cemented the union of the provinces. Their peaceful inhabitants enjoyed and abused the advantages of wealth and luxury. The image of a free constitution was preserved with decent reverence. The Roman senate appeared to possess the sovereign authority, and devolved on the emperors all the executive powers of government. During a happy period of more than fourscore years, the public administration was conducted by the virtue and abilities of Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, and the two Antonines. It is the design of this and of the two succeeding chapters, to describe the prosperous condition of their empire; and afterwards, from the death of Marcus Antoninus, to deduce the most important circumstances of its decline and fall: a revolution which will ever be remembered, and is still felt by the nations of the earth.

That the first centuries of the Empire marked the high point in human history is a view that Hume had already articulated, though he places the apex a little earlier. But the sweep of his account is somewhat larger:

Those who cast their eye on the general revolutions of society, will find, that, as almost all improvements of the human mind had reached nearly to their state of perfection about the age of Augustus, there was a sensible decline from that point or period; and man thenceforth relapsed gradually into ignorance and barbarism. The unlimited extent of the Roman empire, and the consequent despotism of its monarchs, extinguished all emulation, debased the generous spirits of men, and depressed that noble flame, by which all the refined arts must be cherished and enlivened. The military government, which soon succeeded, rendered even the lives and properties of men insecure and precarious; and proved destructive to those vulgar and more necessary arts of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce; and in the end, to the military art and genius itself, by which alone the immense fabric of the empire could be supported. The irruption of the barbarous nations, which soon followed, overwhelmed all human knowledge, which was already far in its decline; and men sunk every age deeper into ignorance, stupidity, and superstition; till the light of ancient science and history had very nearly suffered a total extinction in all the European nations.

“Ignorance and barbarism” is Hume’s version of what Gibbon calls “Barbarism and religion.” But while Gibbon is content to describe what happened to the Roman Empire, ending with the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Hume wants to describe the fate of “all the European nations.”

Gibbon but briefly gestures at renewal. In his final chapter, having declared that his narrative describes “the triumph of Barbarism and religion,” he adds: “But the clouds of Barbarism were gradually dispelled; and the peaceful authority of Martin the Fifth and his successors restored the ornaments of the city [of Rome] as well as the order of the ecclesiastical state.”

Hume, though, wants to do much more in this line. So, to return to the conclusion of his second volume, he writes:

But there is a point of depression, as well as of exaltation, from which human affairs naturally return in a contrary direction, and beyond which they seldom pass either in their advancement or decline. The period, in which the people of Christendom were the lowest sunk in ignorance, and consequently in disorders of every kind, may justly be fixed at the eleventh century, about the age of William the Conqueror; and from that aera, the sun of science, beginning to re-ascend, threw out many gleams of light, which preceded the full morning, when letters were revived in the fifteenth century.

Fascinatingly, Hume believes that the key event, the one that more than any other turned the descent into an ascent, came when the Corpus Juris Civilis of Justinian was rediscovered, in (Hume believes) Amalfi. That provided a direct link to the wisdom of the ancient world: the Justinian Code, which was itself a summary and codification of much older Roman laws, became a standard against which the legal practice of the present day could be measured, found wanting, and, slowly, remedied.

(Gibbon was so strongly committed to his narrative of decline that, though he wrote extensively about Justinian’s reign, he could not grant strong praise to anything that emperor did. If Justinian expanded his empire, that’s a sign of corruption and failure: “The fortifications of Europe and Asia were multiplied by Justinian; but the repetition of those timid and fruitless precautions exposes to a philosophic eye the debility of the empire.” Likewise the attempt to deal with moribund traditions: “Justinian suppressed the schools of Athens and the consulship of Rome, which had given so many sages and heroes to mankind. Both these institutions had long since degenerated from their primitive glory; yet some reproach may be justly inflicted on the avarice and jealousy of a prince by whose hands such venerable ruins were destroyed.” As for the great Code, there’s too much of it and it was badly administered: “The government of Justinian united the evils of liberty and servitude; and the Romans were oppressed at the same time by the multiplicity of their laws and the arbitrary will of their master.” Hume is always more generous.)

As already noted, Hume thinks that the ascent is due to the increase in power and influence of “civility and sciences,” which are both disciplinary: “civility” disciplines the passions of men and thereby brings increasing order to the political system and civil society alike, while “science” is a synonym for the disciplined, the methodical and orderly, pursuit of knowledge. Hume deplores religion because religion — coming as it does in two varieties, the superstitious and the enthusiastic — is consistently antidisciplinary. Superstition refuses the discipline of science, enthusiasm refuses the discipline of civility.

(By the way, I have written about how Hume’s superstition/enthusiasm binary helps to explain our current politics.)

In the first two volumes of his history, Hume covers around 1500 years; in the last four, fewer than 200. And increased documentation is only one reason for that disproportion: more important, for Hume the philosophical historian, is the fact that those 200 years reveal an inconsistent but unmistakable diminishment of enthusiasm and superstition and increase of civility and sciences. To discern the means by which that ascent occurred is, for Hume, the primary reason for studying that history. We know that we rose from barbarism — but how did we rise? If we know that, then we may be able to avoid sinking back into the mire; and should it happen that we do sink again, well, at least we can know the way out.

human voices

My friend Rick Gibson makes a fascinating argument here. You need to read the whole thing, but a brief summary would go like this: No matter how vast the corpus of text on which chatbots currently draw, in order to be successful in the future they will need to have an ever-expanding and ever-developing corpus. They won’t be useful to us unless human beings keep adding high-quality information, high-quality ideas, high-quality text, that they can draw upon.

I’m trying to decide whether this is right — or rather, I know that it’s at least partially right but I’m trying to decide how right it is. I can conceive of certain circumstances in which it would not be true. For instance, programmers often use chatbots to write code for them, and one of the things that they often say is that the code written by bots is verbose and ugly. It gets the job done, sort of, but in a bloated and inelegant way. But it’s easy to imagine that the bloated and inelegant code written by bots will eventually become the norm. Programmers who become habituated to getting their code written or at least drafted by chatbots will never develop a sense of what concise and elegant code is; and when they don’t have that sense they won’t value it and therefore won’t miss it when it’s absent. Elegance in code could just cease to be a thing.

I guess what I’m asking is whether in programming — and in certain other areas, for instance business correspondence — what the bots provide could reshape our sense of what counts as good enough.

I’m thinking here about something I wrote about a few years ago, also at the Hog Blog:

Why can computers sometimes pass a Turing Test? Erik Larson, in his book, points out that in one test a few years ago people were told that the computer was human but not a native English speaker — which didn’t fool everyone who interacted with it but fooled enough people to make some of us worried. Why were the deceived deceived? I suggest that there are two likely answers, neither of which excludes the other.What if that’s what the pervasive presence of AI does? — reduce our mooring to reality sufficiently that we cease to notice the difference between text written by chatbots (however out of date the corpus on which they draw) and actual human language? I think about the phenomenon of young singers singing like Autotune because that’s what they think singing sounds like. Standards of quality, like standards of beauty, are mutable.The first was offered some years ago by Big Tech critic Jaron Lanier in his book You Are Not a Gadget. Lanier writes that the Turing Test doesn’t just test machines — it also tests us. It “cuts both ways. You can’t tell if a machine has gotten smarter or if you’ve just lowered your own standards of intelligence to such a degree that the machine seems smart. If you can have a conversation with a simulated person presented by an AI program, can you tell how far you’ve let your sense of personhood degrade in order to make the illusion work for you?” That is, many of us have interacted with apparently thoughtful machines often enough — for instance, when on the telephone and trying, often fruitlessly, to get to a customer service representative, that we have gradually lowered our standards for intelligence. And surely this erosion of standards is furthered by situations in which, even when by some miracle we do get to speak to another human being, we find that they merely read from a script in a way not demonstrably different from the behavior of a bot. Lanier says flatly that “the exercise of treating machine intelligence as real requires people to reduce their mooring to reality.”