the arc of Hume's history

I’ve been reading David Hume’s massive and magnificent History of England, and it’s generally fascinating — though there are, it must be said, extended passages in which he’s just dutifully relating what his researches have been able to discover about events which are not as well-attested as he would like. At the end of Volume II, when he has completed his narration of the Wars of the Roses with his account of the life and death of Richard III, he heaves a great sigh of relief:

Thus have we pursued the history of England through a series of many barbarous ages; till we have at last reached the dawn of civility and sciences, and have the prospect, both of greater certainty in our historical narrations, and of being able to present to the reader a spectacle more worthy of his attention.

That is, he’s about to enter the era in which increased political and social order (“civility”) and the invention and adoption of the printing press (“sciences”) yield far greater documentation of events.

In a famous essay, Arnaldo Momogliano argued that Gibbon, in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, sought to unite two kinds of historiography that previously had been quite distinct: the antiquarian history of les erudits and the philosophical history of writers like Voltaire. Gibbon was a great fellow for archives and inscriptions and ruins, but he was also determined to tell a story that enlightened and instructed. Hume — writing roughly a generation before Gibbon: the History of England was published between 1754 and 1762, while the Decline and Fall appeared between 1776 and 1789 — is very much the philosophical historian. His virtues, in his own estimation, are those of critical judgment rather than antiquarian assiduity. When he has more documentation, documentation that needs to be sifted and assessed with a shrewdly philosophic eye, his distinctive excellences come into play.

In one important sense his orientation is almost identical to that of Gibbon. Gibbon, famously, begins his history thus:

In the second century of the Christian era, the empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of mankind. The frontiers of that extensive monarchy were guarded by ancient renown and disciplined valour. The gentle, but powerful, influence of laws and manners had gradually cemented the union of the provinces. Their peaceful inhabitants enjoyed and abused the advantages of wealth and luxury. The image of a free constitution was preserved with decent reverence. The Roman senate appeared to possess the sovereign authority, and devolved on the emperors all the executive powers of government. During a happy period of more than fourscore years, the public administration was conducted by the virtue and abilities of Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, and the two Antonines. It is the design of this and of the two succeeding chapters, to describe the prosperous condition of their empire; and afterwards, from the death of Marcus Antoninus, to deduce the most important circumstances of its decline and fall: a revolution which will ever be remembered, and is still felt by the nations of the earth.

That the first centuries of the Empire marked the high point in human history is a view that Hume had already articulated, though he places the apex a little earlier. But the sweep of his account is somewhat larger:

Those who cast their eye on the general revolutions of society, will find, that, as almost all improvements of the human mind had reached nearly to their state of perfection about the age of Augustus, there was a sensible decline from that point or period; and man thenceforth relapsed gradually into ignorance and barbarism. The unlimited extent of the Roman empire, and the consequent despotism of its monarchs, extinguished all emulation, debased the generous spirits of men, and depressed that noble flame, by which all the refined arts must be cherished and enlivened. The military government, which soon succeeded, rendered even the lives and properties of men insecure and precarious; and proved destructive to those vulgar and more necessary arts of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce; and in the end, to the military art and genius itself, by which alone the immense fabric of the empire could be supported. The irruption of the barbarous nations, which soon followed, overwhelmed all human knowledge, which was already far in its decline; and men sunk every age deeper into ignorance, stupidity, and superstition; till the light of ancient science and history had very nearly suffered a total extinction in all the European nations.

“Ignorance and barbarism” is Hume’s version of what Gibbon calls “Barbarism and religion.” But while Gibbon is content to describe what happened to the Roman Empire, ending with the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Hume wants to describe the fate of “all the European nations.”

Gibbon but briefly gestures at renewal. In his final chapter, having declared that his narrative describes “the triumph of Barbarism and religion,” he adds: “But the clouds of Barbarism were gradually dispelled; and the peaceful authority of Martin the Fifth and his successors restored the ornaments of the city [of Rome] as well as the order of the ecclesiastical state.”

Hume, though, wants to do much more in this line. So, to return to the conclusion of his second volume, he writes:

But there is a point of depression, as well as of exaltation, from which human affairs naturally return in a contrary direction, and beyond which they seldom pass either in their advancement or decline. The period, in which the people of Christendom were the lowest sunk in ignorance, and consequently in disorders of every kind, may justly be fixed at the eleventh century, about the age of William the Conqueror; and from that aera, the sun of science, beginning to re-ascend, threw out many gleams of light, which preceded the full morning, when letters were revived in the fifteenth century.

Fascinatingly, Hume believes that the key event, the one that more than any other turned the descent into an ascent, came when the Corpus Juris Civilis of Justinian was rediscovered, in (Hume believes) Amalfi. That provided a direct link to the wisdom of the ancient world: the Justinian Code, which was itself a summary and codification of much older Roman laws, became a standard against which the legal practice of the present day could be measured, found wanting, and, slowly, remedied.

(Gibbon was so strongly committed to his narrative of decline that, though he wrote extensively about Justinian’s reign, he could not grant strong praise to anything that emperor did. If Justinian expanded his empire, that’s a sign of corruption and failure: “The fortifications of Europe and Asia were multiplied by Justinian; but the repetition of those timid and fruitless precautions exposes to a philosophic eye the debility of the empire.” Likewise the attempt to deal with moribund traditions: “Justinian suppressed the schools of Athens and the consulship of Rome, which had given so many sages and heroes to mankind. Both these institutions had long since degenerated from their primitive glory; yet some reproach may be justly inflicted on the avarice and jealousy of a prince by whose hands such venerable ruins were destroyed.” As for the great Code, there’s too much of it and it was badly administered: “The government of Justinian united the evils of liberty and servitude; and the Romans were oppressed at the same time by the multiplicity of their laws and the arbitrary will of their master.” Hume is always more generous.)

As already noted, Hume thinks that the ascent is due to the increase in power and influence of “civility and sciences,” which are both disciplinary: “civility” disciplines the passions of men and thereby brings increasing order to the political system and civil society alike, while “science” is a synonym for the disciplined, the methodical and orderly, pursuit of knowledge. Hume deplores religion because religion — coming as it does in two varieties, the superstitious and the enthusiastic — is consistently antidisciplinary. Superstition refuses the discipline of science, enthusiasm refuses the discipline of civility.

(By the way, I have written about how Hume’s superstition/enthusiasm binary helps to explain our current politics.)

In the first two volumes of his history, Hume covers around 1500 years; in the last four, fewer than 200. And increased documentation is only one reason for that disproportion: more important, for Hume the philosophical historian, is the fact that those 200 years reveal an inconsistent but unmistakable diminishment of enthusiasm and superstition and increase of civility and sciences. To discern the means by which that ascent occurred is, for Hume, the primary reason for studying that history. We know that we rose from barbarism — but how did we rise? If we know that, then we may be able to avoid sinking back into the mire; and should it happen that we do sink again, well, at least we can know the way out.

human voices

My friend Rick Gibson makes a fascinating argument here. You need to read the whole thing, but a brief summary would go like this: No matter how vast the corpus of text on which chatbots currently draw, in order to be successful in the future they will need to have an ever-expanding and ever-developing corpus. They won’t be useful to us unless human beings keep adding high-quality information, high-quality ideas, high-quality text, that they can draw upon.

I’m trying to decide whether this is right — or rather, I know that it’s at least partially right but I’m trying to decide how right it is. I can conceive of certain circumstances in which it would not be true. For instance, programmers often use chatbots to write code for them, and one of the things that they often say is that the code written by bots is verbose and ugly. It gets the job done, sort of, but in a bloated and inelegant way. But it’s easy to imagine that the bloated and inelegant code written by bots will eventually become the norm. Programmers who become habituated to getting their code written or at least drafted by chatbots will never develop a sense of what concise and elegant code is; and when they don’t have that sense they won’t value it and therefore won’t miss it when it’s absent. Elegance in code could just cease to be a thing.

I guess what I’m asking is whether in programming — and in certain other areas, for instance business correspondence — what the bots provide could reshape our sense of what counts as good enough.

I’m thinking here about something I wrote about a few years ago, also at the Hog Blog:

Why can computers sometimes pass a Turing Test? Erik Larson, in his book, points out that in one test a few years ago people were told that the computer was human but not a native English speaker — which didn’t fool everyone who interacted with it but fooled enough people to make some of us worried. Why were the deceived deceived? I suggest that there are two likely answers, neither of which excludes the other.What if that’s what the pervasive presence of AI does? — reduce our mooring to reality sufficiently that we cease to notice the difference between text written by chatbots (however out of date the corpus on which they draw) and actual human language? I think about the phenomenon of young singers singing like Autotune because that’s what they think singing sounds like. Standards of quality, like standards of beauty, are mutable.The first was offered some years ago by Big Tech critic Jaron Lanier in his book You Are Not a Gadget. Lanier writes that the Turing Test doesn’t just test machines — it also tests us. It “cuts both ways. You can’t tell if a machine has gotten smarter or if you’ve just lowered your own standards of intelligence to such a degree that the machine seems smart. If you can have a conversation with a simulated person presented by an AI program, can you tell how far you’ve let your sense of personhood degrade in order to make the illusion work for you?” That is, many of us have interacted with apparently thoughtful machines often enough — for instance, when on the telephone and trying, often fruitlessly, to get to a customer service representative, that we have gradually lowered our standards for intelligence. And surely this erosion of standards is furthered by situations in which, even when by some miracle we do get to speak to another human being, we find that they merely read from a script in a way not demonstrably different from the behavior of a bot. Lanier says flatly that “the exercise of treating machine intelligence as real requires people to reduce their mooring to reality.”

Currently reading: History of England (6 volumes) by David Hume 📚

The court is motivated by statesmanship, which the country sorely needs today. The problem is that this statesmanship is a form of the kind of outcome-oriented policymaking that the court disparages in other contexts. It trusts states to handle the homelessness crisis but not ballot access for insurrectionists, even though the Constitution trusts states with both. It trusts juries to handle fines for securities fraud but not punishment for abuse of the presidency, even though the Constitution trusts juries with both.

I think there are some better things to say about the majority’s decision in Trump — I might write at some point about how it slyly explains to courts just how to prosecute rogue Presidents — but overall I think Baude’s argument is compelling.

I’ve written a kind of mini-manifesto explaining how I’m trying to re-humanize myself, and maybe help a few readers as well.

re-humanization

A couple of years ago I wrote about a shift in my writerly focus from a decade-long inquiry into the enemies of attention to an inquiry into how we might live a human life at a human scale. Those are related themes, of course: identifying and critiquing what Tim Wu calls “the attention merchants” is indeed vital: an ethic and maybe even a theology for our time begins, as I have argued in an essay on Thomas Pynchon, with suspicion of our would-be overlords. But suspicion is only the first step, and a largely useless one unless we’re willing and able to redirect our attention to worthier objects than those being sold to us by the machinery of surveillance capitalism.

But the idea of living “a human life at a human scale” makes sense only if the human is a meaningful category, and therefore one of my related themes in recent years has been the need to recover a belief in the integrity of that category — that is, to help people believe that we have a distinctive bond with, and distinctive obligations to, our fellow humans. (N.B. This is not to say that we have no bond with or obligations to the rest of Creation: the key word in the previous sentence is “distinctive.”)

“A Humanism of the Abyss,” my essay from last year on Oliver Sacks, is one contribution to this cause; my new essay in Harper’s, “Yesterday’s Men: The Death of the Mythical Method,” is another. I’m looking to describe those moments in our experience when the various divisions of our current identity politics fade into the background and something more fundamental forces itself upon us.

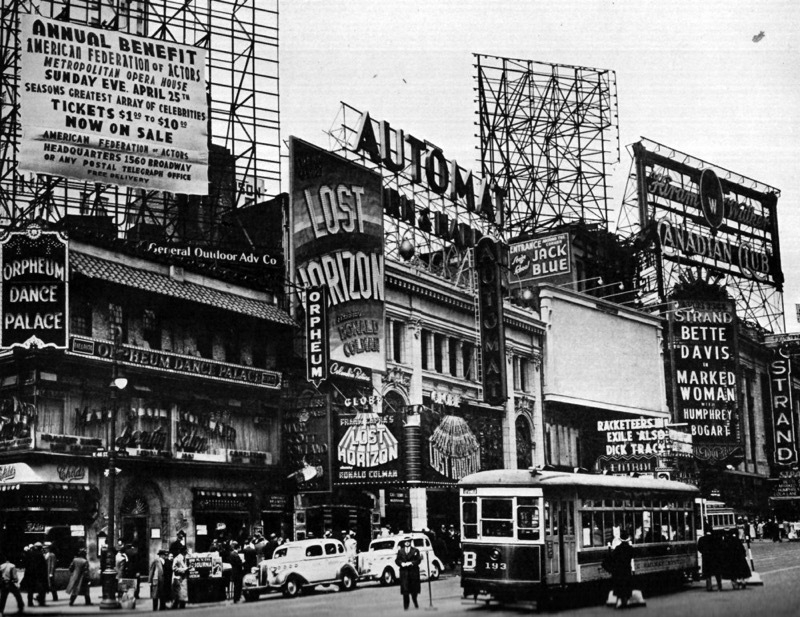

Also: my mind continually returns to the Second World War, because I believe it was in that era — starting in the decade preceding the outbreak of hostilities — that our current antihumanism has its roots. That was the period when modern governments, with modern administrative structures and procedures, started building entire socio-political systems based on fundamental oppositions of race or class. That was the period in which we all became habituated to “seeing like a state.” (And, not incidentally, my writing about anarchism is an exercise in countering that panoptic gaze.)

Another clarification: This is not to say that racism and class antagonism did not exist prior to the Second World War, but the intimate connection between race/class/sex and the administrative state is a necessary prerequisite for our identity politics today, and that began in the lead-up to the war, first in Nazi Germany and then elsewhere. I often wonder whether the internment of Japanese-Americans would have been thought of had the Nazis not provided a pre-existing playbook for such action. But then, of course, the Nazi system drew on the principles of Taylorism, which in turn drew on experiments in workplace management pioneered several decades earlier by Robert Owen — nothing in this world is wholly new, wholly without precedent, but I think the Nazis did a lot to show just how far Taylorist principles could go in organizing a whole society and especially in excreting its racial refuse. (And then, of course, in making us all self-Taylorizing, building our entire lives on principles of efficiency and productivity.)

I often meditate on this passage from Antony Beevor’s history of the Second World War:

On 15 December [1944], Hitler and his entourage moved in his personal train to the Adlerhorst (Eagle’s Nest) Führer headquarters at Ziegenberg, near Bad Nauheim. Rundstedt’s headquarters were already in the adjacent Schloss. To the horror of the generals, Martin Bormann’s Nazi Party Chancellery came too, and Bormann complained that the facilities were insufficient for all his typists. Nazi bureaucracy, both in Berlin and at local levels, seemed only to increase as disaster threatened, no doubt to give the impression that the Party was still in control of events. Instructions, directives and regulations cascaded forth on every subject just when the transport and therefore also the postal system were collapsing under the weight of Allied bombing.

Of course, this entire system is built on maniacal hatred — I have heard historians say that the Nazis fought as long as they did in a hopeless cause because that was the only way to keep the trains going to Auschwitz — but I think it’s even more strongly built on a fantasy of perfect control, the channeling of hatred into a flawless System. And the very presence of the ovens, the need for them, is evidence of an imperfect system.

Orwell’s “boot stamping on a human face — forever” is something that will only happen when a system of control has failed. As long as it’s properly functioning it will produce — and produce via documentation — what Foucault called “docile bodies,” and what Auden, some decades earlier, had already envisioned as

An unintelligible multitude,

A million eyes, a million boots in line,

Without expression, waiting for a sign.

Once the degenerates and subhumans have been exterminated, the “unintelligible multitude” remains.

I think we can all agree that such systems, even in imperfect form, are radically dehumanizing — we feel this to some degree even in our most trivial encounters with bureaucratic administrivia — but what acts, what commitments, what beliefs, what loves, are required to begin a rehumanizing movement? That’s the key question I’m asking myself these days. And I believe the answers are to be found largely in the arts, especially works of art that precede the Tayorization of the world and the self. It is not the technological futurists who will show is the way out of this iron cage; it is our artful ancestors.

A final word: this is a question everyone should be asking, I think, but especially my fellow Christians. For what is the Gospel if not a message to human beings? It is a message that concerns the whole of Creation, but human beings are the ones to whom the Good News is addressed. And I don’t know how people can hear that News if they don’t know themselves and their neighbors as fellow humans, under the same Judgment, and offered the same Salvation.

“To be interested in ‘the future’ is a symptom of demoralization and debility.” — T. S. Eliot, 1927

donkey work

John Gregory Dunne, from The Studio:

The Studio was simplicity itself to write. It was mainly a matter of transcribing and rearranging my notes. That there were no surprises—I knew exactly what I was going to do—was for me the problem. Writing is essentially donkey work, manual labor of the mind. What makes it bearable are those moments (which sometimes can last for weeks, months) when the book takes over, takes on a life of its own, goes off in unexpected directions. There were no detours like that in The Studio. My notes were like plans for a bridge. Writing the book was like building that bridge.

This chimes with my experience. The two books I most enjoyed writing are Original Sin and The Year of Our Lord 1943, because they posed serious structural challenges. It was not obvious to me how those stories might best be told.

Ted Gioia: “When I first came to Silicon Valley at age 17, the two leading technologists in the region were named William Hewlett and David Packard. They used their extra cash to fund schools, museums, and hospitals — both my children were born at the Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital — not immortality machines, or rockets to Mars, or a dystopian Internet of brains, or worshiping at the Church of the Singularity. […] Bill Hewlett had more wisdom than ego. He invested in the community where he lived — not the Red Planet. Instead of promulgating social engineering schemes, Hewlett and Packard built a new engineering school at their alma mater, and named it after their favorite teacher. They wouldn’t recognize Silicon Valley today.”

Man Hunt (1941)

In theory, Fritz Lang’s Man Hunt faced the same problem that many other Hollywood films of the same era (Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, for instance) faced: How to be anti-Nazi while maintaining a fig leaf of objectivity — a necessary fig leaf, given the supposed neutrality of the United States. But this movie is about as anti-Nazi as it’s possible to be. That said, opposition to Nazism isn’t what the movie is about. To explain why I say that, I have to tell the story.

Alan Thorndike (Walter Pidgeon) is a famous English big-game hunter who is caught in the woods near Berchtesgaden and accused of attempting to assassinate Adolf Hitler. Under interrogation by a Nazi official (played with exquisite sliminess by George Sanders) he denies the charge, but is told that he will not be released, indeed will be killed, unless he signs a confession. He refuses, but eventually escapes to London, pursued by Nazis.

Overall, the movie doesn’t have a very Lang-like look and feel, but there’s a terrific pursuit scene in the Underground that reminds me strongly of M.

In any event: the Nazis chase Thorndike about the city and eventually, though quite accidentally, into the arms of a cockney girl called Jerry (Joan Bennett), whom he charms. She falls hard for him, though the feeling is not quite mutual. He’s attracted to her but not besotted; she’s a kid to him. In the end Thorndike kills his Nazi pursuers, though not before they find Jerry and kill her, because she refused to betray his location. (There’s a strong dose of poetic justice in the way he does this, but that’s one detail I won’t spoil.)

Thorndike is wounded in the final confrontation with his enemy, and two scenes follow. In the first, Thorndike is in the hospital, deliriously replaying in his mind his time with Jerry; in the second, he parachutes out of an airplane — not under orders, but on his own initiative — and into Germany. His descent is accompanied by much bombast. It’s the same kind of pseudo-patriotic noise that defaces the conclusion of Foreign Correspondent.

What the bombast (including a final voiceover) obscures is the real point of the story, which is this: Thorndike is on a suicide mission. At a moment when the Nazis control most of Europe and any meaningful contesting of their continental domination is years away, he floats down to German soil carrying only a high-powered hunting rifle. At the beginning of the film he had told his interrogator that he didn’t enjoy killing any more — he had come to prefer the “sporting stalk” in which he finds and targets his quarry but doesn’t bother to pull the trigger — but now his only thought is killing. He will not come back; he does not want to come back.

It is clear that he has but one goal: atonement. He had stumbled into Jerry’s life, charmed her, allowed her to assist him, and by those means he had led her straight to her death. And the only way he can think to atone is to kill as many Germans as he can and then suffer death himself. Man Hunt isn’t a patriotic drama; it’s an existentialist tragedy.

Still some wildflowers down here in the Hill Country.

writing time

on the edge

Above you see what I believe was the key moment in today’s match between Portugal and Slovenia. After having a penalty saved, astonishingly, by Jan Oblak, Cristiano Ronaldo collapsed in tears, and I mean collapsed: during the break between the two halves of extra time, his shoulders were shaking, he was inconsolable. Several teammates came up to hug him and pat him on the back, but only Palhinha gave him what he needed, which was a stern pull-up-your-socks talking-to.

Given the excessive deference Portuguese football exhibits towards Ronaldo — manifested today by allowing him to take several terrible free kicks which should have been taken by Bruno Fernandes, with Ronaldo in the box trying to get his head on the ball — Palhinha’s initiative was brave, and it may have saved the match. Without his intervention, would Ronaldo have been able to get himself together for the penalty shootout? Maybe. But I’m not sure.

Surely Ronaldo is the most unlikeable of the truly great footballers. He has always been petulant, whiny, preening, and selfish, and has often been on the edge of losing self-control altogether. As a starlet at Manchester United, he took more dives than Greg Louganis … but eventually he realized that his behavior was counterproductive — he was not getting calls that he deserved because the refs assumed that he was diving once again — and he stopped. Just stopped.

Ronaldo strikes me as a narcissistic asshole who wants so desperately to be great at football that he manages — with enormous difficulty — to control his bad disposition sufficiently that it doesn’t prevent greatness. His devotion to preparation is, I think, unparalleled. Consider for instance how good he is with his “off” leg — he’s scored around 175 left-footed goals in his career — and think about how many thousands of hours of practice enabled that success. His conditioning is likewise superlative: he’s 39 years old and just played 120 minutes, but of all the Portugal players he’s the one I’m least worried about being tired for the Friday match with France.

It would have been so easy for his own temperament to destroy his career, but it didn’t. I don’t like him, I don’t like him one bit, but I have to admire him for that. I’m talking here only about his play, not about the rest of his life, but: Whether his demons are inbuilt or whether he has indulged them, they’ve been afflicting him his entire career, and yet in every essential way he has throttled them. That’s remarkable.

All that said, I wish he’d have missed that second penalty as well, and that Slovenia had sent him home.

P.S. Palhinha’s full name is João Maria Lobo Alves Palhares Costa Palhinha Gonçalves.

UPDATE after the Portugal loss to France, from Jonathan Liew:

In a way, it’s hard not to feel resentful of him: resentful of the way this grand, galaxy-sized occasion is ultimately reduced to a function of one man’s ego. This could have been an all-time great quarter-final, and instead a part of it was stolen: stolen ball possession, stolen attention, stolen minutes from better players who actually deserve to be there, rather than a pure anachronism trotting out simply because no one has the clout to tell him not to.

Liew points out that Ronaldo was the only Portugal player on the pitch not to console Joao Felix after the kid missed his penalty. He just turned and walked away, even though he had received consolations in the previous match.

Siena Cathedral. (Test post.)

Very glad to see the NYT printing a lengthy obituary of the great Kinky Friedman, though they don’t emphasize the fact that his run for Governor of Texas featured the best campaign slogan ever: “How Hard Could It Be?”

I deleted my big-blog post on today’s big SCOTUS ruling. I think I have a useful point, but today’s not the time to make it. People will be too heated. I’ll save the post and publish it in 2034.