I gave a couple of chatbots a list of movies with dates and asked them to organize the list in chronological order. Gemini could do it, ChatGPT 4o could not (though it said it did). For all these bots the failure points are quite different.

Well, the Euros were shaping up to be a great tournament until England took the pitch. That was dire — hypercautious, unimaginative, and low-energy. But since they eked out a win, I’m sure Southgate will give us more of the same. ⚽️

Currently reading: The Studio by John Gregory Dunne. This little book has a hundred great stories but my favorite is this: When planning the television series Custer, 20th Century Fox TV execs knew who they wanted to play Crazy Horse: Toshiro Mifune. This did not happen, for good reasons, but I can’t help wondering…. 📚

more on beauty

Ortega y Gasset’s entire essay [on “The Dehumanization of Art”] is brilliant, and should be required reading in college humanities programs — it’s more relevant now than ever before…. But instead it’s almost never read. Instead, grad students are assigned Walter Benjamin’s essay from 1935 on “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” — which embraced mass production as a “progressive” way to provide “visual and emotional enjoyment” in an “intimate” manner to millions of people. I have sympathy for Benjamin, but he was betrayed by the mass producers — much as we are getting betrayed by today’s tech overlords of creative ‘content’.

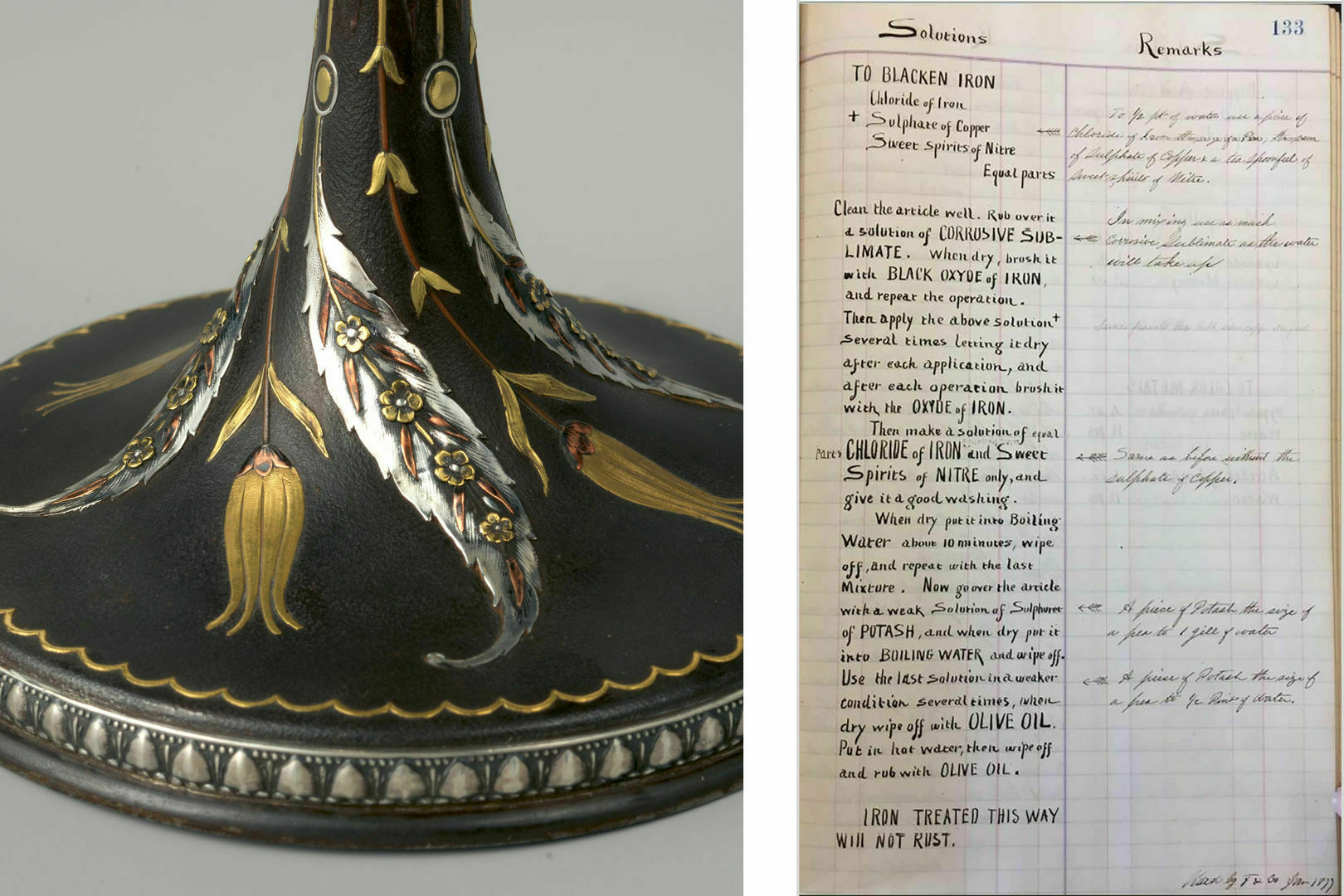

A great post by Mr. Gioia, and consistent with my recent comment that a Ruskinian account of contemporary culture must begin by attending to beauty. And we might begin that endeavor by considering Aphorism 19 from Ruskin’s Seven Lamps of Architecture: “All beauty is founded on the laws of natural forms.”

Zach Rausch: “This is the challenge of our time: How do we balance the desire to give kids individual freedom and new digital technologies with our desire to give them a stable, tight-knit community?” But what if we can’t? What if we have to choose?

Why am I shooting film again, after so many years? In part because of what Craig Mod says here:

We have access to such abundance — a billion photos, infinite video at our fingertips, the ability to fill our closets with clothes for a hundred bucks, a near-zero-cost amusement bonanza straight to the grave — that the move to “scarcity” mediums like vinyl or cassettes (!!) or film or obsessing over 70mm IMAX prints does make sense (in a cockamamied way). Sixty years ago, jazz kissa owners saw an “arbitrage opportunity” in music, in record ownership. Today that opportunity is lost. Today we have all the music we could want all the time. Ten thousand YouTube channels to explain each album. Transcriptions of every instrument. So what do we do? We arbitrage attention by hunting for records of albums on Spotify to put on our shelves. We load a clunky (mostly) light-tight box with celluloid and pretend like every shot is our last. These are ostensibly pointless acts (“Just tell Siri to play the album, just use your phone to take the photo!”) but in reality they’re goofy forms of prayer for us godless folk, prayer for honing attention, for cultivating intimacy, for looking a little more closely in a world beset by distraction, seductive distraction.

starting over

Around a month ago, I mentioned that I had just read and really enjoyed Robin Sloan’s novel Moonbound. And that’s true! But what I didn’t say at the time is that I definitely didn’t get the most out of my reading experience, didn’t have full concentration as I read. And I know why. It was because of one page near the beginning of the galley I read, a page with three words on it:

As I read, I kept looking back at that page, as though hoping that the words would dissolve and be replaced by the promised cartography. Because when I am reading a work of fiction there are few things I love more than a map.

I think I would have missed the map even if I hadn’t been told that there would be one, but to know that a map was being made but I did not have it was agonizing. Thus my inconsistent attentiveness.

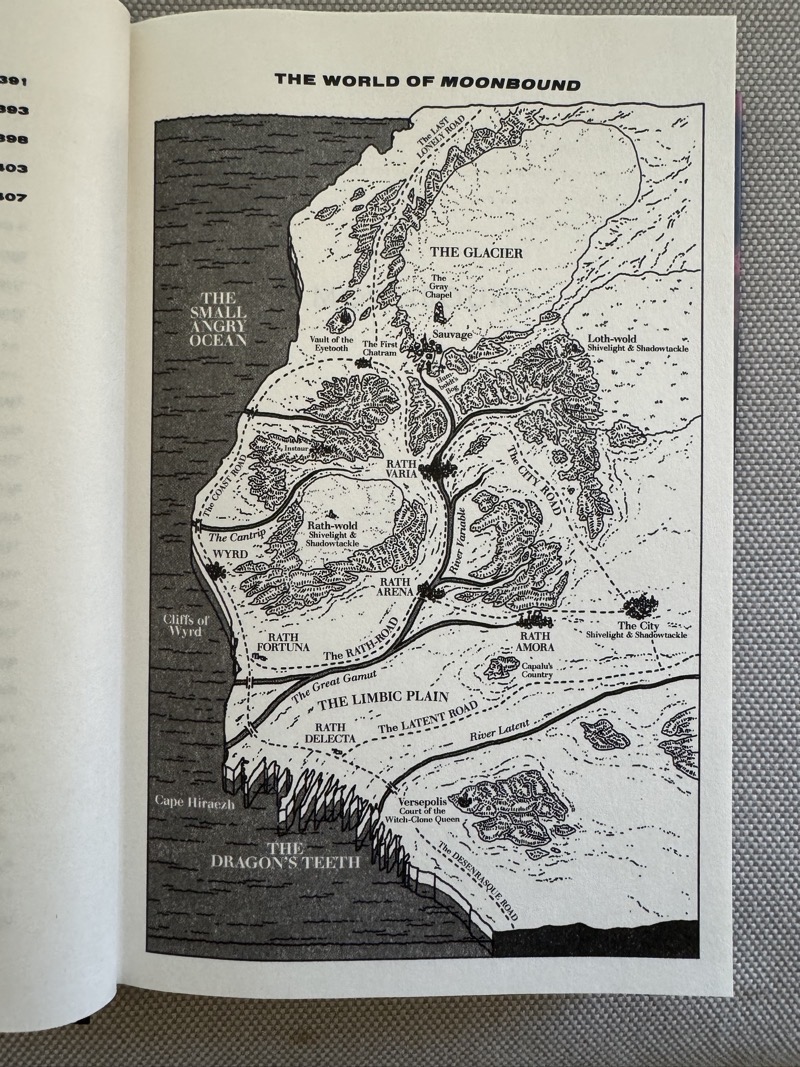

But today, this very afternoon, my very own hardcover copy of the book arrived, and when I opened it up I saw this:

Ah. Ah yes. I will now be re-reading Moonbound, and this time I’ll get the full and proper experience.

Shooting on film — with a Nikon F100 — for the first time in many years. The natural bokeh is great, and the texture, but wow am I out of practice. I need to re-learn setting exposure and even proper focusing. (Also: there are so many varieties of film to choose from now!)

Here’s a long post, with many links, explaining how I’ve sorta-kinda-in-a-way written a book in blog posts.

the wanderers and the city

My earlier posts in this series (which began by reading Genesis but has since expanded) are:

- Orientation to the topic

- On fertility

- The country and the city

- An outline of the Pentateuch

- Character

The Pentateuch concludes with the death of Moses and the arrival of the children of Israel at the doorstep of the Promised Land. As in the next books (Joshua and Judges) they consolidate their position, we’re moving, as I noted in an earlier post, from a world of nomadic pastoralists to a world of city dwellers — or, anyway, a world in which the embodiment of the Israelite identity is a city, Jerusalem, conceived first as the residence of the King and only later as the center of the cult of Yahweh.

This change raises certain questions about the theology and ethics of building, especially building a city, and as it happens I wrote a series of posts about that some years ago on my old Text Patterns blog:

- Building

- Building 2

- Building 3: practices of making

- Building 4: creative fidelity

- Building 5: cunning works

- Building 6: diaspora

The invocation of the Diaspora leads to a reflection on the city that in Scripture opposes Jerusalem: Babylon. Here are the entries in my Encyclopedia Babylonica:

I stopped writing then because I was confused about a number of things. But I am now seeing certain connections. The series on building (which focused on the Davidic era) and the series on Babylon (which focused on the era that ended the Davidic line) are, properly speaking, elements in a larger theology of the city, which I explored by writing about Augustine’s City of God:

- The City and the City

- Archetype and Antithesis

- Hypothesis

- Secondary Epic

- Political Theology

- City and Church

- A Digression on Longtermism

- Causes

- A Digression on Reading

- Parallels

- Ends and Means

- The City of God Coming Down

- Last Things

(There’s some overlap to these series because they were written independently of one another and sometimes in forgetfulness.) And I have many other posts and essays that seem to be on unrelated subjects but may not be. For instance, Ruskin — my admiration for whom I recently reaffirmed — begins The Stones of Venice by claiming that three cities associated with the mastery of the sea stand above all others: Tyre, Venice, and London. His theology of art and architecture is also a theology of the city, meant for Londoners, as the successors to the Venetians, to heed. There’s even a strange passage early in Stones in which Ruskin claims that all three of Noah’s sons founded cultures that contributed to the rise of architecture, thereby reconnecting the theme of the City to the book of Genesis.

Related: there is a long and powerful tradition of writing about London as the city, the paradigmatic or exemplary city, the city as a “condensed symbol,” to return to a theme from my last post: this is what Blake does repeatedly, and Dickens, and H. G. Wells, especially in Tono-Bungay. There are some powerful connections between Tono-Bungay and Little Dorrit that I want to explore in a future post.

It’s strange that I have written a book’s worth of reflections on all this stuff. But what does this non-book say? Heck, what do I even mean by “all this stuff”?

I think these concerns arose in my mind because (a) I was, and still am, frustrated by the ongoing dominance of H. Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture, a book that still establishes the categories for thinking about how Christians live in “the world”; and (b) I felt that a richer, deeper picture is offered, however obliquely, in the poetry and prose of W. H. Auden in the decade following the end of the Second World War. (It’s noteworthy, I think, that Auden’s work is contemporaneous with Niebuhr’s: that WW2 prompted full-scale reconsiderations of the ideal character of culture and society is what my book The Year of Our Lord 1943 is all about.) Auden, instead of writing about “culture,” writes about “the city,” and that reformulation strikes me as especially resonant and full of promise, especially given the prominence of the Jerusalem/Babylon opposition in the Bible.

Now, Auden writes about these matters in The Shield of Achilles, which I have edited — but he writes about them more extensively in his previous book Nones, which I may also edit. Even if I don’t get the chance to make a critical edition of that collection, I’m going to be re-reading it, and maybe after I do I’ll have a better idea of how to put all these thoughts, which have obviously been occupying my mind for quite some time, into better order.

But whether I should try to turn all this into an actual book? I have my doubts about that. For one thing, few if any publishers would be interested in publishing something that is largely available online for free. For another — and this actually may be more important — do all these thoughts really belong in a book, between covers, with a beginning an ending? Some projects ought not to be closed and completed; some projects ought to be ramifying and exploratory. I suspect this is one such project. I may have more to say about that in future posts.

Also, here’s Robin explaining in a video the language/script/typeface he developed for his fabulous new novel Moonbound. I love the fact that Robin’s one previous video was posted fourteen years ago. I can’t wait to see what he posts in 2038.

Surprising moment from this interview with Robin Sloan:

[Gibson-Faulkner] Theory is, of course, the great policy planning framework of the Anth, which is what I call human civilization at its apex—our near future. The idea is that it’s a system for imagining and executing big projects that actually works. The theory emerges from the intersection of two maxims. First, there’s William Gibson: “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.” Then, there’s William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Mashing those together, we get an interesting view of the present, not as a point on a continuum, but rather a smear, a bleed, a diffusion of events and possibilities. (It’s well-known that early Gibson-Faulkner theorists were also influenced by Alan Jacobs and his concept of “temporal bandwidth”.)

To which I 🤯 and ☺️. (It’s really Thomas Pynchon’s concept more than mine, but I’ll take credit.)

George Lois’s library — in his apartment in the West Village — is my kind of workspace. And the apartment, at $5,600,000, is a bargain!

An outstanding post by Mike Sacasas about technology and work — the kinds of work we value and the kinds of work we ought to value.

I wrote about character in the Pentateuch.