intrinsic values

In his poem “Little Gidding,” written during World War II, T. S. Eliot wrote that the Cavaliers and Puritans who fought in England’s Civil War, in the 17th century, now “are folded in a single party.” The same already seems true of Vendler and Perloff. Today college students are fleeing humanities majors, and English departments are desperately trying to lure them back by promoting the ephemera of pop culture as worthy subjects of study. (Vendler’s own Harvard English department has been getting a great deal of attention for offering a class on Taylor Swift.) Both Vendler and Perloff, by contrast, rejected the idea that poetry had to earn its place in the curriculum, or in the culture at large, by being “relevant.” Nor did it have to be defended on the grounds that it makes us more virtuous citizens or more employable technicians of reading and writing.

Rather, they believed that studying poetry was valuable in and of itself.

I like this essay, but I’m mentioning it here because Kirsch makes use of a common phrase that has always puzzled me: “valuable in and of itself.” Variants: “intrinsically valuable” and “valuable for its own sake.” I have never known what that means — or even could mean. Because: if you ask people to say more about valuing something for its own sake, they end up saying that it gives them pleasure or delights them or fascinates them. But to pursue something because it delights or fascinates you is not pursuing it for its own sake — it’s pursuing it for the sake of the delight or fascination.

When people say that something is “valuable in and of itself,” I think what they mean is simply that it has no economic or social value — note Kirsch’s contrast between intrinsic value and something valued because it “makes us more virtuous citizens or more employable technicians of reading and writing.” Someone might say that when we say some artifact or experience is intrinsically valuable we’re saying that it does not have any instrumental value — but isn’t a song that delights me instrumental to that delight? And isn’t that okay?

So I think that when we describe something as having intrinsic value, what we really mean is that the value it provides is higher than or nobler than any furthering of crassly economic or social ambitions. We’re indirectly and somewhat sloppily appealing to a hierarchy of goods. And maybe — especially in the context of debates about liberal education, which is at least partly the context of Kirsch’s essay — we should be more explicit about that, and conscious of what our hierarchy is and why we affirm it.

Apple may just have created the most tone-deaf advertisement in the history of advertising. I think I’m gonna go outside and smash my iPad with a trumpet.

Most alarmingly, kids in third and fourth grade are beginning to stop reading for fun. It’s called the “Decline by 9,” and it’s reaching a crisis point for publishers and educators. According to research by the children’s publishers Scholastic, at age 8, 57 percent of kids say they read books for fun most days; at age 9, only 35 percent do. This trend started before the pandemic, experts say, but the pandemic accelerated things. “I don’t think it’s possible to overstate how disruptive the pandemic was on middle grade readers,” one industry analyst told Publishers Weekly. And everyone I talked to agreed that the sudden drop-off in reading for fun is happening at a crucial age—the very age when, according to publishing lore, lifetime readers are made. “If you can keep them interested in books at that age, it will foster an interest in books the rest of their life,” said Brenna Connor, an industry analyst at Circana, the market research company that runs Bookscan. “If you don’t, they don’t want to read books as an adult.”

Obviously this is bad news, but let’s remember the context: Do kids do anything for fun these days? They’re not allowed to play, only to have “supervised leisure activities.” Everything is grinding and striving and measured performance. Are they even given enough time alone to make reading possible? If kids go from school to music lessons to the sport of the season, or to various after-school programs, and they’re given phones to occupy their every free instant, of course they won’t read. But then, in such cases not-reading isn’t the worst of their problems.

R.I.P. Steve Albini — a wonder of a recording engineer who had a simple and clear and unshakable commitment to what he thought recorded music should sound like: a live performance. Human beings playing their instruments and singing, in the earth’s atmosphere, surrounded by a built environment.

Me, a couple of years ago, stating a thesis that I’m still committed to: “In any given community, there will be a profound divide between those who believe that the most dangerous lies are the ones told by our enemies and those who believe that the most dangerous lies are the ones we tell ourselves.”

Laura Brown, The Great Lakes of North America

back to the brows

After reading various writings about the brows — including, first of all, this unsent letter by Virginia Woolf and this 1949 essay by Russell Lyne, I find myself impatient and wanting to cut to the chase. I’ll come back to these matters later when I’ve had more time to think them over, but in the meantime, some Theses:

- A work of art can largely confirm the expectations of those who encounter it, largely thwart those expectations, or touch any point between those extremes. This is true of all the arts, but for present purposes I will speak only of fiction.

- These expectations can be of many kinds, but the most commonly invoked expectation involves difficulty: How hard-to-track, hard-to-comprehend do we expect and want a book to be?

- The reader who demands that all of his or her expectations be met is often called a lowbrow reader; the writer whose work habitually meets such readers’ expectations is often called a lowbrow writer.

- The reader who craves surprise, excess, extremity, who is impatient with work that confirms typical expectations, is often called a highbrow reader; the writer whose work consistently violates norms and transgresses standards is often called a highbrow writer.

- N.B.: Higher-browed readers often want to have their aesthetic expectations challenged, but not their moral ones. Almost no one wants that. (But they get it sometimes, from some writers. George Eliot and Vladimir Nabokov are good examples — I’ll write about them, in this regard, one day.)

- “Highbrow,” “middlebrow,” and “lowbrow” are all characteristically pejorative terms, meant to insult, though in some cases (e.g. the piece by Woolf above) a writer will claim and even treasure the insult. See for comparison the history of such words as “Quaker” and “Methodist.” If Virginia Woolf does not think that your novel sufficiently resists your readers’ expectations, she will call you and your readers middlebrows; Graves and Hodges in the same circumstance will call you and your readers lowbrows. (They don’t mention C. P. Snow in their book, but if they had they’d probably have called him a lowbrow writer, but something like The Search is clearly meant for the educated reader.)

- The three brow-terms are most commonly used by people who are or believe themselves to be highbrows, though they may dislike that language and (implicitly or explicitly) put ironic scare-quotes around it.

- Even the most challenging writer will not always want to read works that constantly challenge or repudiate his or her expectations. Auden used to say that great masterpieces demand so much of their readers that you simply can’t take one on every day, not without either trivializing the experience or exhausting yourself.

- It is characteristic of highbrows’ use of these distinctions — see the Woolf letter quoted above and T. S. Eliot’s encomium to the music-hall entertainer Marie Lloyd, which employs the related socio-economic terms “aristocrat,” “middle-class,” and “worker” — that they articulate some alliance of themselves and the lowbrows against the middlebrow.

- Lowbrow readers do not know, and if they knew would not care, about this supposed alliance.

- Middlebrow readers and writers alike are often aware of the disdain of them felt by highbrows, and may respond either by defensiveness or mockery. (Think of Liberace’s famous response to his critics’ scorn for his music: “I cried all the way to the bank.” Funny to think of that line having a known origin, but it does.)

- For a long time now there has been no genuine lowbrow reading. Those who insist on all their expectations being fulfilled can get that hit much more efficiently through movies, TV, Instagram, TikTok, etc.

- The brow-discourse is conceptually distinct from, but overlaps considerably with, genre-discourse. For instance, detective novels that adhere strictly to the conventions of the genre — the Ellery Queen stories, for instance — will often be called lowbrow, while those that frequently deviate from the conventions — the later novels of P. D. James, for instance, or Sayers’s Gaudy Night — may get called “highbrow” or, more likely, “literary fiction.”

- The tripartite brow-discourse is much less useful than a more nuanced and more detailed account of readerly expectations, one which is sensitive to the ways different genres can generate different sets of expectations, and respond to those expectations in diverse ways.

UPDATE 2024–05–27: It suddenly occurs to me that I have been confusing two quite different things: the three-brow distinction as a way of talking specifically about reading books and as a way of talking about culture then as a whole. If you’re talking about reading, then of course there are lowbrow readers, lowbrow books, etc. But if you’re talking broadly about culture, then in an age when the popularity of movies, TV, and social media is at least an order of magnitude — I use that term with care; most people use it to mean “a whole lot” — I repeat, at least an order of magnitude greater than the popularity of reading, then anyone who reads books at all is ipso facto a middlebrow.

UPDATE 2024-06-05: I have received a salutary word of criticism from my friend Francis Spufford:

It is slightly nerve-wracking saying this, Professor Jacobs, but you are uncharacteristically misreading the Woolf. Yes, she's a vile old snob in literary as much as in social terms. But I don't think you can adduce what she says here about the ‘common reader’ as proof of that. To my ear, she's being ironic throughout. She says, with stagey astonishment, that the common reader fails to measure up to proper critical standards, insisting on reading for such low satisfactions as pleasure, amusement, and a sense of meeting real human beings. She observes, as if baffled, that the survival or otherwise of literature over the long term is determined by the reputation of a work among these amateurs, and not among professors or theoreticians at all. How ghastly! Just for once, I'm sure the irony here means that Woolf is putting herself on the side of what's common. There is a hole on her snobbery, a subject on which she feels like an insurgent rather than a possessor, and it's to do with her lack of a university education. Unlike Sayers at Somerville, Virginia Stephen did all her reading at home, devising her own critical standards based on her own reactions. She is a common reader, by her own lights. Indeed she publishes two books of critical essays called The Common Reader and The Common Reader 2. She's claiming the right to read Cervantes for fun, rather than the right to borrow three romances a week from the Boots Circulating Library, but it's still a claim to centre pleasure. Virginia on the barricades! Virginia 'Che’ Woolf!I think Francis is almost wholly right here, though I do believe Woolf’s irony is accompanied by snobbery. Anyway, criticism taken gratefully on board, to be deployed later.

I just posted a new letter to my BMAC supporters.

Playing this morning: Khruangbin’s A LA SALA. ♫

This from Austin Kleon is great:

One of the reasons I didn’t connect with writer Nicholson Baker’s recent book about learning to draw, Finding a Likeness, is that he couldn’t seem to enjoy the process of drawing unless the drawing resulted in what he felt was visual accuracy. I remember watching him learn to draw on Twitter and Instagram and noticing a point at which he seemed to get much better, and saying so. Upon reading the book, I realized that point was when he started tracing photographs to begin his drawings….

I admire Baker greatly as a fiction writer, and we have the same general idea about the value of drawing as a way of noticing the world. But how you get there… that’s where we differ wildly. The last way I personally want to spend my time drawing is by taping a piece of paper to a computer screen and tracing a digital image with a pencil. I want drawing to take me out into the world, away from my screens and get me to look at it with my own eyeballs.

It’s pub day for my critical edition of Auden’s The Shield of Achilles!

Our new bee attractor.

Doug Stowe: “My proposal … was as follows: Start with the basic elements from Greek philosophy — earth, air, fire, and water — and divide the incoming freshman class according to their elemental inclinations. Then provide concrete activities for student engagement along those lines.”

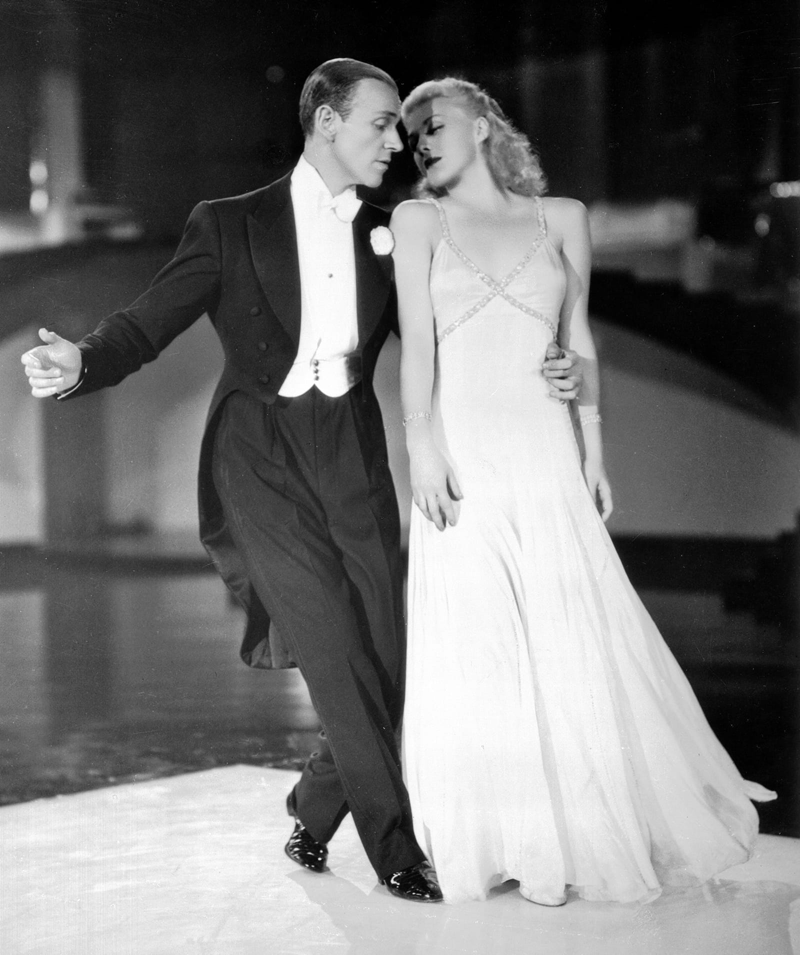

elegance personified (really)

Last night Teri and I watched Swing Time, and afterwards played a little game: We went back to the dance scenes and tried to pause at instants when Astaire and Rogers didn’t look elegant. Couldn’t do it. At every moment they are balanced and poised, they’re perfect images of grace.