I wrote a post on how anarchic childhoods can make more politically mature adults.

Waxahatchee’s new album is great.

adult children

I think there’s a strong causal relationship between (a) the overly structured lives of children today and (b) the silly political stunts of protestors and “activists.”

As has often been noted, American children today rarely play: they engage in planned, supervised activities completely dictated by adults. Those of us who were raised in less fearful times spent a lot of time, especially during school vacations, figuring out what to do: what games to play, what sorts of things to build, etc. To do all this, we had to learn strategies of negotiation and persuasion and give-and-take. I might agree to play the game Jerry wants to play today on the condition that we play the game I want to play tomorrow. You could of course refuse to negotiate, but then people would just stop playing with you. Over time, therefore, kids sorted these matters out: maybe one became the regular leader, maybe they took turns, maybe some kids opted out and spent more time by themselves. Some were happy about how things worked out, some less happy; there were occasionally hurt feelings and fights; some kids became the butt of jokes.

I was one of those last because I was always younger and smaller than the others. (Story of my childhood in one sentence.) That’s why I often decided to stay home and read or play with Lego. But eventually I would come back, and when I did I was, more or less, welcomed. We worked it out. It wasn’t painless, but it wasn’t The Lord of the Flies either. We came to an understanding; we negotiated our way to a functional little society of neighborhood children.

But in today’s anti-ludic world of “planned activities,” kids don’t learn those skills. In their tightly managed environments, they basically have two options: acquiescence and “acting out.” And thus when they become politically aware young adults and find themselves in situations they can’t in conscience acquiesce to, acting out is basically the only tool in their toolbox. So they bring a microphone and speaker to a dinner at someone’s house and demand that everyone listen to their speech on their pet issue. Or they blockade a bridge, thereby annoying people who probably agree with their political news and giving decision-makers good reason to condemn them. Or they dress up in American flags and storm the U. S. Capitol building. And they act out because they can’t think of anything else to do when political decisions don’t go their way. After all, they’ve been doing it all their lives.

When kids do this kind of thing, we’re not surprised; we say, hey, kids will be kids. When adults do it, we call them assholes. We raise our children in such a way – this is my thesis – that we almost guarantee that they’ll grow up to be assholes. Congratulations to us! We’ve created a world in which, pretty soon, the Politics of Assholery will be the only kind of politics there is.

P.S. This is why I’m interested in anarchism! As I have said several times, the difference between libertarianism and anarchism is simply this: the goal of libertarianism is to expand the realm of individual freedom, while the goal of anarchism is to expand the realm of collaboration and cooperation. We need more anarchic childhoods today to have a more mature and constructive politics tomorrow.

The Internet’s New Favorite Philosopher | The New Yorker:

Maret is part of a growing coterie of readers who have embraced [Byung-Chul] Han as a kind of sage of the Internet era. Elizabeth Nakamura, a twentysomething art-gallery associate in San Francisco, had a similar conversion experience, during the early days of pandemic lockdown, after someone in a Discord chat suggested that she check out Han’s work. She downloaded “The Agony of Eros” from Libgen, a Web site that is known for pirated e-books. (She possesses Han’s books only in PDF form, like digital samizdat.) The monograph argues that the overexposure and self-aggrandizement encouraged by social media have killed the possibility of truly erotic experience, which requires an encounter with an other. “I’m like queening out reading this,” she told me, using Gen Z slang for effusive enjoyment—fangirling. “It’s a meme but not in the funny way — in the way that it’s sort of concise and easily disseminated. I can send this to my friends who aren’t as into reading to help them think about something,” she said.

“This guy’s thinking has changed my life but of course that doesn’t mean I’m willing to pay for his books.”

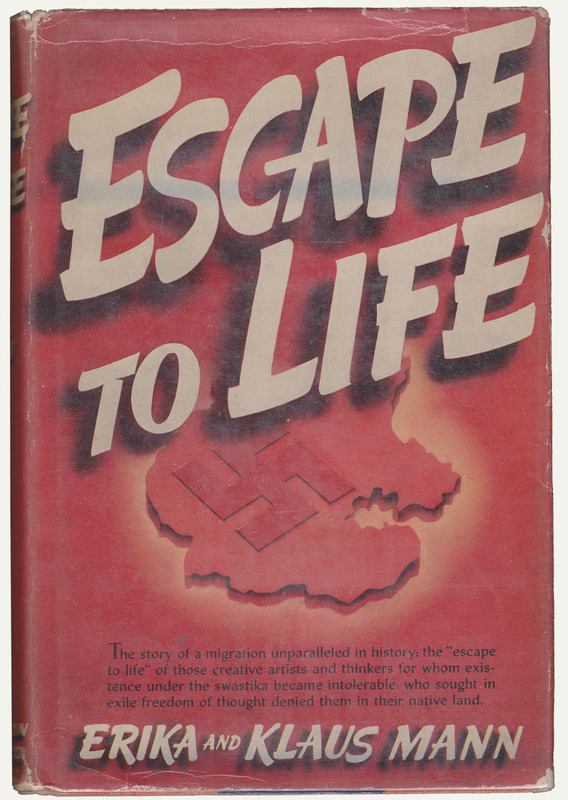

Wystan and Erika

The couple above are W. H. Auden and Erika Mann. The photo was taken by a student at The Downs School, where Auden was then teaching. Erika, the daughter of the novelist Thomas Mann and an ardent opponent of Nazism, had been living in England but was in imminent danger of being repatriated to Germany. To prevent that from happening, Auden agreed to marry her. (Both were gay and not otherwise interested in matrimony.) On June 15, 1935 they were married in Ledbury, a town near the school. This photo was taken around that time, perhaps even on their wedding day.

Thomas and Katia Mann were very worried about Erika’s safety: had she been repatriated, a lengthy prison term was the best that she could have hoped for, especially since on her mother’s side she was of Jewish descent. Thomas and Katia were themselves safely on their way to New York City, traveling by ocean liner, when, on June 16, they received a terse and to-the-point telegram:

ALL LOVE FROM MRS AUDEN

In January of 1939, Auden and his friend Christopher Isherwood arrived in New York City and were greeted at the pier by Erika and Klaus. They all drove down to Princeton to meet Papa and Mama Mann, and Life magazine sent a photographer to capture a family photo:

A happy reunion!

Wystan and Erika never divorced, so for decades Auden got to enjoy making jokes about “my father-in-law." When Erika died in 1969 some of the obituaries noted that she was survived by her husband, the poet W. H. Auden — a piece of information that came as rather a shock to some of her friends, and his.

All that said, after their marriage Auden was very eager for his parents to meet Erika and insisted that she travel to Birmingham with him so they could receive the parental blessing. (“My husband is a tyrant,” Erika sighed in a letter to a friend, not thinking Birmingham a sufficiently interesting or beautiful city to make a visit worthwhile.) They remained friends always, and Isherwood thought that later there was even “a touch of eroticism” to their relationship. So to call it a “marriage of convenience” is perhaps not to tell the whole truth.

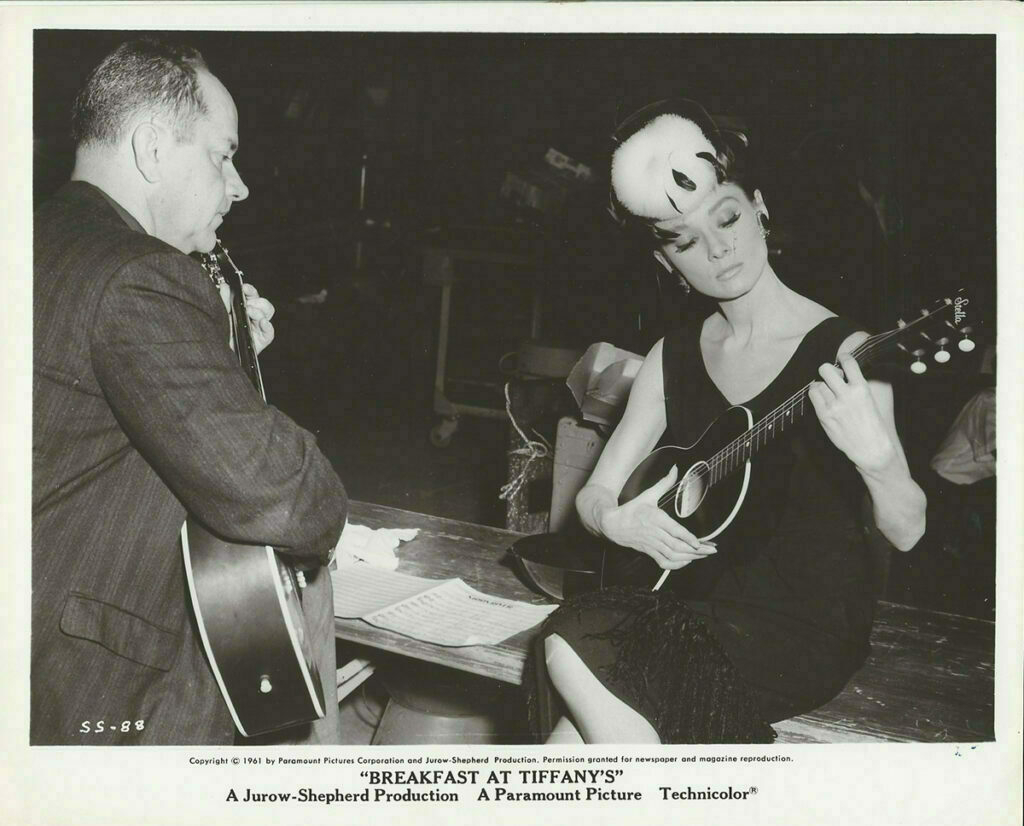

Audrey Hepburn taking guitar lessons — so she can play as she sings “Moon River.”

Someone asked me today about my micro.blog avatar, which is one of Paul Klee’s hand puppets, the one called The Philistine.

More stuff of mine related to that essay on “rewilding the internet”: I’ve written about mechanization and monoculture, about living in a plural world, and about monism and pluralism.

Me on rewilding the internet plus having a home on the open web — and note that micro.blog is part of that home.

rewilding

The essay by Maria Farrell and Robin Berjon on “Rewilding the Internet” is absolutely essential — and you might know that I would think so if you read my essay from a few years back on “Tending the Digital Commons.” (See also my reflections on “manorial technocracy” and the tag, visible at the bottom of this post, “open web.”) Our metaphors are slightly different but our theme is the same.

It’s noteworthy, I think, that those of us who care about the internet and love the best versions of it tend to think ecologically.

Farrell and Berjon:

Ecologists have re-oriented their field as a “crisis discipline,” a field of study that’s not just about learning things but about saving them. We technologists need to do the same. Rewilding the internet connects and grows what people are doing across regulation, standards-setting and new ways of organizing and building infrastructure, to tell a shared story of where we want to go. It’s a shared vision with many strategies. The instruments we need to shift away from extractive technological monocultures are at hand or ready to be built.

Just as a diverse “pocket forest” is the surest way to regenerate urban vegetation, a global network with multiple different ways “to internet” is the best insurance policy for future innovation and resilience. We need to rewild the internet for the future, for our freedom to build tools and spaces, and to share knowledge, ideas and stories that haven’t been anticipated by the internet’s current overlords and cannot be contained.

This is precisely why this blog is on the open web rather than on Substack or any of the other walled gardens. To be sure, I can afford to do it this way, with the occasional contribution from my Buy Me a Coffee page — I have a day job and don’t depend on blogging to feed my family and pay my mortgage. If I were utterly dependent on this blog I might do things differently — but only after I had tried every way possible to make it work on the open web.

I really do think that the internet, in its original open form, is an amazing thing and a genuine contributor to human flourishing — but the occlusion of the open web by the big social media companies has been a disaster for our common life and for the life of the mind. My plan, and my hope, is to keep going here long after I have lost the ability to publish anywhere else. This is my home on the web and also the place where I can most fully be myself as a writer. And that’s worth a lot.

Daniel Parris: “A New York Times analysis of Spotify data revealed that our most-played songs often stem from our teenage years, particularly between the ages of 13 and 16…. Indeed, YouGov survey data indicates a strong bias toward music from our teenage years, a phenomenon that is consistent across generations.” Curiously, I listen to almost nothing that I listened to in my teenage years, the one exception being Bob Dylan’s music, which was a part but not a big part of my adolescent listening. (Dylan became really central for me when I was in college, though.)

Nadine Chahine: “A typeface is a series of conversations happening simultaneously between different characters. For example, in the Latin script, the lowercase b talks to the d, talks to the p, talks to the q, and they respond. So there is this ongoing conversation between the b, d, p, and q, and then there is this other conversation happening between the m, n, and h. And then all the diagonals, like the v, the w, the x, and the y, are talking to one another as well. At some point, you realize that these conversations are all happening in the same space, and the groups start talking to one another as well. The role of the type designer is to facilitate these conversations.

Trying to get a pic of one of our roses, I am confronted by a photobomber

Start your weekend on a good note: listen to Sweet Honey in the Rock sing “Run Molly Run”

Butterflies and bees 🐝