A great post by Sara Hendren AKA @ablerism on places whose architecture helps us to cultivate certain “limiting virtues.”

More on the benefits of handmind.

FYI: The people at Standard Ebooks produce carefully-edited, well-formatted, free e-books. Project Gutenberg is an amazing resource, but its texts are sometimes sloppily prepared; every Standard Ebook I’ve downloaded looks great. (I have also contributed $$ to the project.)

Dorothy L. Sayers: Vitality, bullying and bounce.

bounce

J. R. Ackerley, author of that remarkable book My Dog Tulip, worked for the BBC for many years and in that capacity oversaw the production of The Scoop (1931), a detective story written by six authors, each of whom read his or her contribution on-air. Dorothy L. Sayers coordinated the project; she was probably the only person who could have gotten the shy and retiring Agatha Christie to participate. But she and Ackerley continually butted heads, as he wished to provide editorial oversight that Sayers flatly rejected.

Some years later Ackerley wrote in a BBC memo,

So far as I recall Agatha Christie, she was surprisingly good-looking and extremely tiresome. She was always late sending in her stuff, very difficult to pin down to any engagements and invariably late for them. I record these memories with pain, for she is my favourite detective story writer.Whether Sayers was indeed “bullying,” or simply a woman who refused to be dictated to by men who were accustomed to dictating to women, is a matter of dispute. Later, when she was writing the plays that would become The Man Born to be King, she responded to an interfering producer thus: “Oh no you don’t, my poppet!” That producer was removed from the project — and replaced by one of the greatest theatrical producers of the twentieth century, Val Gielgud (brother of the actor John). However “difficult” she might have been, she couldn’t be dispensed with; in the end, it was almost always her critics who had to give way.Her success as a broadcaster has made less impression upon me. I believe she was quite adequate but nothing more; a little on the feeble side, if I recollect aright, but then anyone in that series would have seemed feeble against the terrific vitality, bullying and bounce of that dreadful woman Dorothy L. Sayers.

But “vitality, bullying and bounce” is a great phrase, and many people found DLS similarly intimidating, and too energetic for comfort. But not everyone disliked the bounciness. On her death, C. S. Lewis wrote, “I liked her, originally, because she liked me; later, for the extraordinary zest and edge of her conversation — as I like a high wind.” And in a memoir Val Gielgud wrote, “Miss Sayers is professional of the professionals. She can tolerate anything but the shoddy or the slapdash. Of all the authors I have known she has the clearest, and the most justifiable, view of the proper respective spheres of author and producer, and of their respective limitations. She is authoritative, brisk, and positive.”

Vitality, bounce, zest, edge, authoritative, brisk — a high wind indeed. No wonder responses to her were so mixed. She’s gonna be so much fun to write about.

My colleague Philip Jenkins wrote about Kipling’s story “The Gardener,” and I wrote something in response.

The Gardener

I am very pleased that my colleague Philip Jenkins has written about Rudyard Kipling’s “The Gardener,” one of the finest short stories in the world. His care not to spoil the story is exemplary, but it’s virtually impossible to say anything meaningful about the story except in light of its conclusion.

So you should read the story as soon as you can.

There’s one element of the story that’s hotly debated, and I want to weigh in on that, but I also want to avoid spoilers, so I am posting my thoughts on another page: this one.

Reading the obituaries for John Barth, I find myself thinking how odd it must be to outlive your reputation in the way he did, to be famous at thirty and then continue to write for several decades after people stopped noticing. But I am endorsing with wild enthusiasm his response to people who criticized him in the Sixties for not being involved in campus protests: “The fact that the situation is desperate doesn’t make it any more interesting.”

And one more: a Marie-Alice Harel illustration from Howl’s Moving Castle.

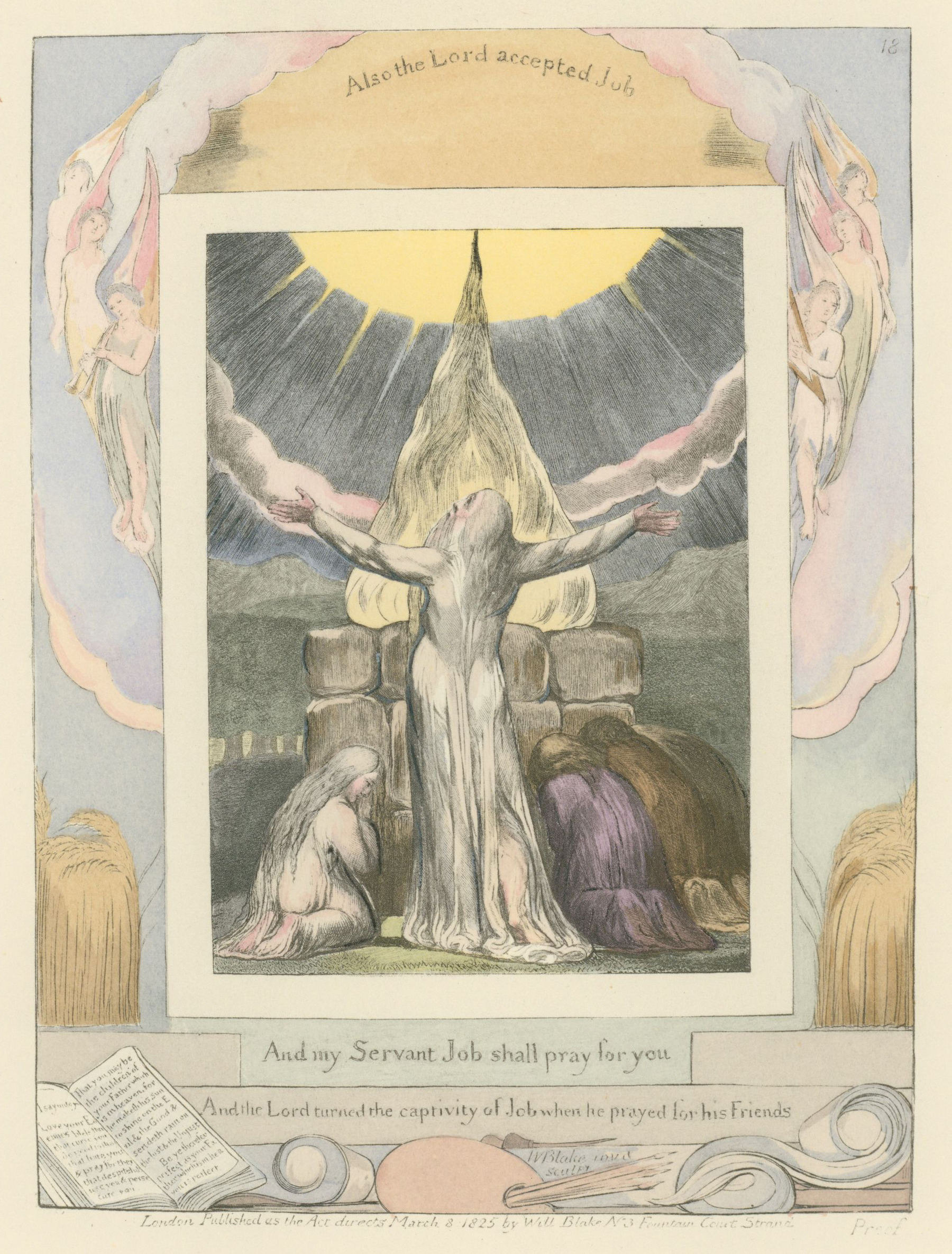

Also from the Folio Society, a Clive Hicks-Jenkins illustration from Beowulf.

The wood engravings of Harry Brockway — this one of the creature made by Victor Frankenstein.

a letter from Karl Barth

On 7 September 1939, a week after the Wehrmacht invaded Poland and thus began the Second World War, the great theologian Karl Barth wrote, in German, from his home in Switzerland to a woman in England. “You too must be shocked by the events of our day,” he wrote. “But I am happy that this time England did not want to let another ‘Munich’ happen, and I hope also for the poor German people that now the end of its worst time (which I have witnessed intimately) has at least begun.” Tragically, war had returned to Europe — but the hapless policy of of appeasement was over, and now the end of Hitler, and of Nazism, could, however dimly, be foreseen.

But to acknowledge the war was not the purpose of Barth’s letter. Rather, he wanted to ask this woman for permission to translate two of her theological writings, and also to seek answers to a few questions about the texts. Barth did not make a habit of translating non-German texts — in fact, the only translation he had published was of a sermon by John Calvin — but in these contemporary writings he had found something that he thought his audience would particularly benefit from reading. Moreover, this woman’s fiction had helped him to learn English better; perhaps even more to the point, he had read her novels “with particular interest and admiration.”

The author to whom Barth wrote was Dorothy L. Sayers. Twenty years later he remarked that, in 1939, she had been “familiar to me as the author of a whole series of detective novels — at once thrilling, cultured, and thoughtful. The fascinating thing about these books for me was the visible connection in them between a humanism of the best Oxford tradition and a pronounced mastery in the technique which is essential to literary engagement in this genre.” But at that time he had no idea that she was a Christian, and when a Scottish friend suggested that he read some of her theological essays, he was surprised to learn of their existence — and even more surprised to find them stating most clearly and forcefully certain points about the beauty, power, and sheer drama of Christian doctrine that were dear to his own heart. (However, he did discern, and even in that introductory letter told her that he discerned, a strain of “semi-Pelagianism” in her theology, a comment that she found amusing and inaccurate.)

The works he sought to translate had originally appeared in 1938 in the Times of London: “The Greatest Drama Ever Staged” and “The Triumph of Easter,” later published together in a short book. Barth, having had his questions answered by Sayers, duly produced his translation, but in the chaos that inevitably accompanies wartime set it aside and did not return to it until 1959, two years after Sayers’s death. At that time he wrote,

The special gift of the author, which is evident in her earlier work, certainly remained with her in this later phase of her writing as well — something to which the present little book bears witness. In the following pages, she has spiritedly and successfully come out against dogma’s reputation for “tediousness”; in her manner of taking it up and discussing it, its effect is certainly anything but tedious! … For having vigorously made the message of the gospel her own in breathless astonishment over its central content, and for having recounted it in a way that is open to the world, yet undaunted, quick-witted, and without any hint of apology — but above all, in a way that is joyful and that causes joy in turn — for all of this, regardless of how one might relate to the ins and outs of her thinking at particular points, one must be grateful to her.

“In a way that is joyful and that causes joy in turn” — what a lovely tribute. The source of that joy may be found described in that essay on Easter. Here’s an excerpt:

“Then Judas, which had betrayed Him, when he saw that He was condemned,... cast down the pieces of silver in the temple, and departed, and went and hanged himself.” And thereby Judas committed the final, the fatal, the most pitiful error of all; for he despaired of God and himself and never waited to see the Resurrection. Had he done so, there would have been an encounter, and an opportunity, to leave invention bankrupt; but unhappily for himself, he did not. In this world, at any rate, he never saw the triumph of Christ fulfilled upon him, and through him, and despite of him. He saw the dreadful payment made, and never knew what victory had been purchased with the price.

All of us, perhaps, are too ready, when our behaviour turns out to have appalling consequences, to rush out and hang ourselves. Sometimes we do worse, and show an inclination to go and hang other people. Judas, at least, seems to have blamed nobody but himself, and St. Peter, who had a minor betrayal of his own to weep for, made his act of contrition and waited to see what came next. What came next for St. Peter and the other disciples was the sudden assurance of what God was, and with it the answer to all the riddles.

If Christ could take evil and suffering and do that sort of thing with them, then of course it was all worth while, and the triumph of Easter linked up with that strange, triumphant prayer in the Upper Room, which the events of Good Friday had seemed to make so puzzling. As for their own parts in the drama, nothing could now alter the fact that they had been stupid, cowardly, faithless, and in many ways singularly unhelpful; but they did not allow any morbid and egotistical remorse to inhibit their joyful activities in the future.

Now, indeed, they could go out and "do something" about the problem of sin and suffering. They had seen the strong hands of God twist the crown of thorns into a crown of glory, and in hands as strong as that they knew themselves safe. They had misunderstood practically everything Christ had ever said to them, but no matter: the thing made sense at last, and the meaning was far beyond anything they had dreamed. They had expected a walk-over, and they beheld a victory; they had expected an earthly Messiah, and they beheld the Soul of Eternity.

It had been said to them of old time, "No man shall look upon My face and live"; but for them a means had been found. They had seen the face of the living God turned upon them; and it was the face of a suffering and rejoicing Man.

The refusal to “allow any morbid and egotistical remorse to inhibit their joyful activities in the future” is a key point for Sayers, and something essential for understanding certain elements of her own life — but that’s a story for me to tell in my biography of her.

The story of this correspondence is well-told in an article by my former colleague David McNutt. In this post I have used David’s translation of Barth’s reflections on Sayers.

Couple this piece on west Texas “sky islands” with one of my own on the same subject.

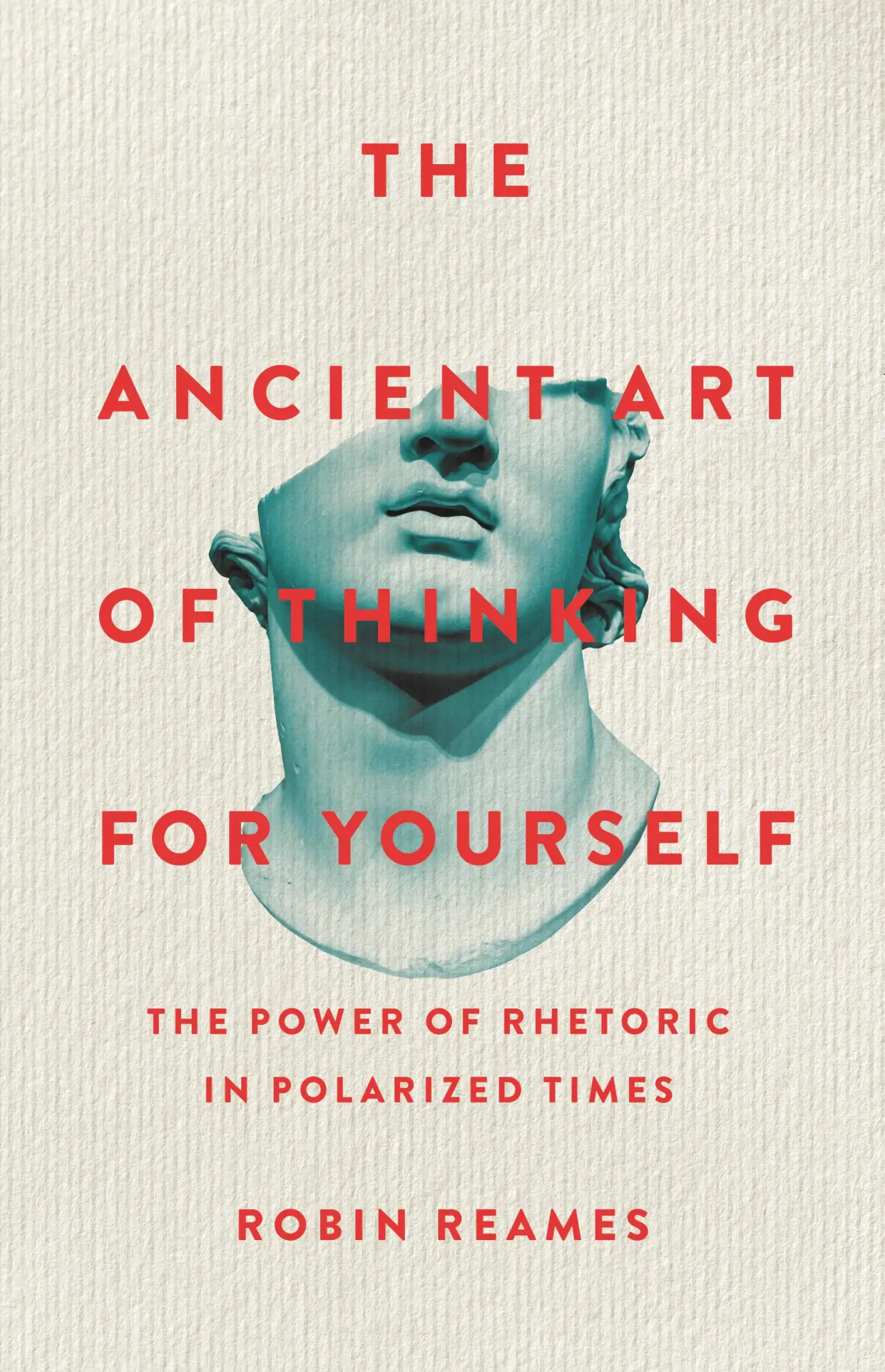

Y’all have heard me say this before, but one of the very best things about my job is seeing the amazing things that my students end up doing. This new book by (my former T.A.!) Robin Reames is just superb, full of wisdom about what it means to think — and speak, and even listen — rhetorically.

Campus is looking nice this cool (for Texas) spring morning.

Max Read: “It sometimes feels like Instagram designed Threads with ‘context collapse’ as a goal to be met instead of a hazard to be avoided…. This is a platform designed around a purpose it cannot fulfill, on an app built to undermine it, with an audience transposed from another social network with a completely different purpose. To me, it is a miracle that anyone is using it at all, but one lesson of the internet is that you should never underestimate the power of a blank text box with a blinking cursor for compelling users to contribute.”