Max Read: “It sometimes feels like Instagram designed Threads with ‘context collapse’ as a goal to be met instead of a hazard to be avoided…. This is a platform designed around a purpose it cannot fulfill, on an app built to undermine it, with an audience transposed from another social network with a completely different purpose. To me, it is a miracle that anyone is using it at all, but one lesson of the internet is that you should never underestimate the power of a blank text box with a blinking cursor for compelling users to contribute.”

Trimming the abelia this morning, I remembered my old handmind in Covidtide post.

This Ted Gioia piece echoes something I’ve been saying for years: see this tag on my blog.

against the factory of unreason

Dear readers, I have returned! — and I say unto you, it might be interesting to read my reflections on my students’ reading ability in conjunction with Emma Green’s report on classical Christian education.

The report is a curious one. She clearly strives to be fair, and acknowledges that the supporters of classical education are more diverse — racially, culturally, and politically — than the typical New Yorker reader is likely to expect. That said, there is an unintentionally comical moment when she confronts classical Christian homeschoolers with their failure to teach Hebrew — this, in a society which every year graduates hundreds of thousands of students from high school who can’t read or write basic English, and in which three-fourths of the population are completely monolingual. (You call yourself a school and you don’t teach Hebrew? Gotcha!) And Green’s conclusion is disappointingly hand-wavy, as though to say that while Those People may not be all we thought they were, still, we ought somehow to be worried about them.

Now, Green isn’t writing about American education in general, rather about one specific movement. But I think we should pull back a bit from that movement to see the larger picture, which is this: A surprisingly large and rapidly growing body of Americans have looked at what the educational establishment is offering and have said, No thank you. From kindergarten through university, that establishment has decided that its job is not to teach any particular skills or bodies of knowledge, but rather to perform certain quite specific political attitudes; to strike poses and teach students to strike the same poses. (It’s a purely performative leftism — it has nothing to do with implementing any policies preferred by the left, you know, as they existed back in the day when the left and right actually had preferred policies instead of contenting themselves with tribal hostilities. This is especially true of elite institutions, which are, after all, hedge funds with attached universities. DEI and similar endeavors are merely ways to camouflage the actual principles that govern such institutions. And the rhetoric trickles down to the non-elite schools, which reflexively copy those whose status they aspire to.)

However, it seems that many parents would prefer their children to learn something substantial. And this enrages the educational establishment and its enablers in the political sphere, who will brook no criticism, even when what their favored groups choose to perform is plain racial hatred, especially of Jews. A “factory of unreason” is what they’ve built, and they’ll do anything they can to prevent people from opting out of labor in that factory.

I am a fan of almost anything that disrupts the hegemony of this fatuously self-righteous and profoundly anti-intellectual educational establishment, which exists not to lift up the marginalized and excluded but rather to soothe the consciences of the ruling class. May the forces of disruption flourish.

After what felt like a very long Lent, I almost achieved liftoff this morning when we got to the Gloria of Mozart’s Spatzenmesse. So gorgeously festive.

Jane Goodall on her 90th birthday: “When I look back over my life, I mean, my goodness, the coincidences that led me to the path where I am now were quite clearly points where I could have said yes or no. It depends whether you think there’s just this life or something beyond, I happen to think there’s something beyond. I feel I was born with a mission. Right now, that mission is to give people hope. So when I get exhausted, I look up there and say: ‘You put me in this position, you bloody well help me get through the evening.'”

Angus is so happy when his people come home.

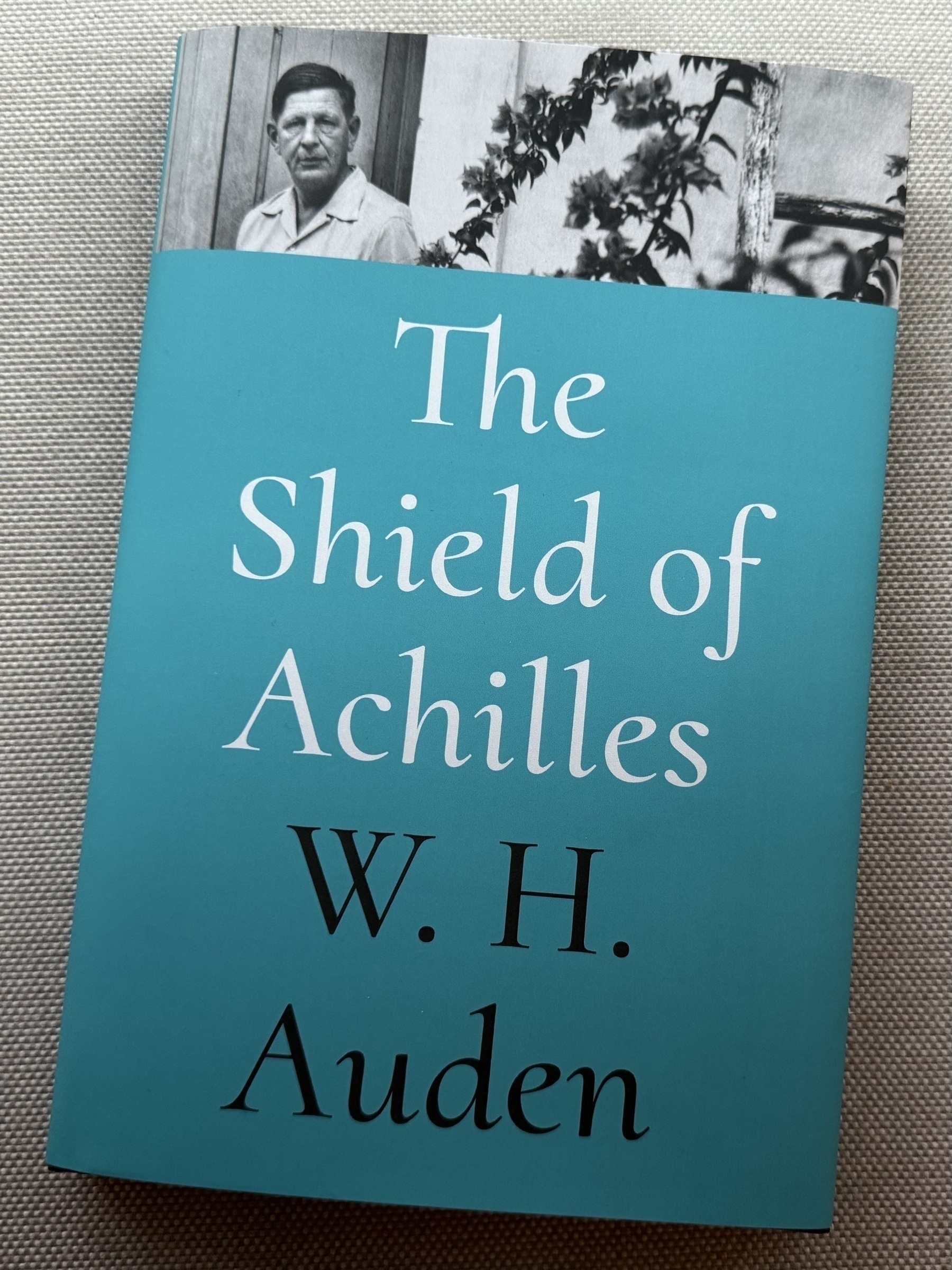

An Easter present for me — author’s (or rather editor’s) copy. So beautifully made. The people at PUP are genuine masters of their crafts.

Here’s the second installment of my conversation with Phil Christman about Auden.

An astonishing carving that may stay in the U.K. — but the art’s the thing, this day, this week.

I talked with Phil Christman about Auden and especially The Shield of Achilles: here’s the first installment of that conversation.

Over at my Buy Me a Coffee page, I wrote about what I’ll be up to for the next few years.

Last post before returning to Lenten silence: I’m really honored to have a place in the new edition of my buddy Austin Kleon’s newsletter. Never thought of myself as someone who could generate text for posters, but maybe that’s my new thing!

I have learned so, SO much about movies from David Bordwell, and am genuinely grieved to learn of his death. R.I.P. The tribute from Damien Chazelle quoted in that post is especially telling.