Lazy day.

DHH is exactly right: Apple has become too powerful, and with that power has come a sense of entitlement, and with that sense of entitlement has come a shortsighted pettiness and vindictiveness. I don’t want to support such a company, in part because I don’t have the bandwidth to go full Linux at the moment, but in. Larger part because, while I don’t want to support Apple, I do want to support the amazing developers who have created the software that makes my Mac a joy to use: people like Bare Bones, Panic, and Rogue Amoeba.

It’s noteworthy, I think, that all three of those developers are either exclusively or primarily focused on the Mac as opposed to iOS, and it’s with regard to iOS that Apple has behaved most despicably. So maybe the best approach for me is to try to go all-in on the Mac and avoid iOS — a move I’ve long been tempted to make anyway.

Also: I just realized that I first wrote about using Linux twenty-two years ago. If breaking from the Mac was hard then, it’s nearly impossible for me to contemplate now.

Just discovered that Terrence Malick, Marilynne Robinson, and Joni Mitchell were all born in November 1943.

Origen may … have been the first church father to study Hebrew, “in opposition to the spirit of his time and of his people,” as Jerome says; according to Eusebius, he “learned it thoroughly,” but there is reason to doubt the accuracy of this report. Jerome, however, was rightly celebrated as "a trilingual man" for his competence in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and Augustine clearly admired, perhaps even envied, his ability to “interpret the divine Scriptures in both languages.” […] But it seems safe to propose the generalization that, except for converts from Judaism, it was not until the biblical humanists and the Reformers of the sixteenth century that a knowledge of Hebrew became standard equipment for Christian expositors of the Old Testament. Most of Christian doctrine developed in a church uninformed by any knowledge of the original text of the Hebrew Bible.

Whatever the reasons, Christian theologians writing against Judaism seemed to take their opponents less and less seriously as time went on; and what their apologetic works may have lacked in vigor or fairness, they tended to make up in self-confidence. They no longer looked upon the Jewish community as a continuing participant in the holy history that had produced the church. They no longer gave serious consideration to the Jewish interpretation of the Old Testament or to the Jewish background of the New. Therefore the urgency and the poignancy about the mystery of Israel that are so vivid in the New Testament have appeared only occasionally in Christian thought, as in some passages in Augustine; but these are outweighed, even in Augustine, by the many others that speak of Judaism and paganism almost as though they were equally alien to "the people of God" — the church of Gentile Christians.

Surely this de-Judaizing is the most important (and troubling) way in which the era of the early Church Fathers differed from the Apostolic beginnings of the Church. It is fascinating to contemplate an alternate history of Christendom in which Jews and Christians remained in regular conversation and debate.

Something I often think, prompted tonight by seeing Jamal Murray (6'4") standing next to Nikola Jokic and Joel Embiid (both 7'0"): If you’re an NBA guard, you spend your working life around people who make you look tiny, but then everywhere else you’re an unusually large person. The contrast must be weird.

Damon K: “A positive, progressive change to this system benefiting more people is not going to come from the top - that is what these latest facts and figures illustrate above all. It is up to the rest of us to find a way to make streaming technology work for the majority of musicians. At UMAW, we have been developing a plan to bring more streaming income to more recording musicians, and we will be going public with details very soon. Support us when we do. And join us if you can!”

The mysterious Roman dodecahedra.

A wonderful collection of Milton Glaser book covers.

Listening to the legendary Bill Evans Trio Village Vanguard sessions. Forty-five years later, I got to hear Motian play with Bill Frisell and Ron Carter a few blocks from the Vanguard at the Blue Note. They were wonderful. 🎵

Blizzard conditions in Waco

I wrote a bit about what I’m teaching this term and how it will affect my blogging.

looking ahead

Lately I’ve been posting in How to Think mode — HTT as the tag here calls it: I’ve been writing about various common-all-too-common errors in reasoning and how they might be avoided. But I’m about to change direction for a while.

When I was a young faculty member at Wheaton College, a college that prides itself on “the integration of faith and learning,” I quickly realized that there was a fundamental mismatch between my knowledge of my academic discipline, which was fairly sophisticated, and my understanding of the Christian faith, which was woefully underdeveloped. I was only 25 years old when I began teaching at Wheaton; I had not grown up in a Christian home and indeed had only been a Christian for around five years; I had a lot to learn. But at least I grasped that point.

And I was richly blessed in my neighbors, for I worked in the same building with Mark Noll, Roger Lundin, Bob Webber, and Arthur Holmes, among others. I relentlessly peppered them with questions, and especially sought recommendations for books I could read to give me an adequate understanding of the full range of Christian thought. I did not understand that I was asking for something that I couldn’t achieve in a lifetime. Gradually it dawned on me that Christian thinking about the arts and humanities was richer and deeper and more extensive than I could have imagined; and then, also gradually, my scholarship and non-scholarly writing too became more and more informed by and rooted in that great and complex tradition.

My experience was somewhat like that of the Methodist theologian Thomas Oden, who when invited to teach and write about pastoral care could but draw on what little he knew about then-contemporary models of psychological counseling. It was only when he asked himself whether Christians, who had been doing pastoral care for 2000 years, might know a little bit about the subject that he began the great series of books on pastoral theology for which he is best remembered. Like me, Oden discovered that the Christian tradition in his chosen field was more extensive and powerful than he had anticipated, and he drank deeply from the well of that tradition for the rest of his life.

Well, for me one thing led to another, and I now have one of the longest job titles in the American academy: the Jim and Sharon Harrod Endowed Chair of Christian Thought and Distinguished Professor of the Humanities in the Honors Program. The second half of that title I’ve had for a decade now; the first half is new. I am pleased and honored and excited by the prospect of becoming an official advocate for the great Christian tradition that I have been talking about in this post.

Partly because of this new role, and partly by accident, I am this semester — for the first time, in a teaching career that now exceeds forty years — teaching only Christian writers. (I have had many semesters in which I didn’t teach any Christian writers at all, though usually there’s been a mix.) I am teaching, for Baylor’s Great Texts program, a course called Great Texts in Christian Spirituality; and I am teaching a new course, one I designed to express my chief interests as the new Harrod Chair: The Christian Renaissance of the Twentieth Century.

The new course is devoted to exploring the extraordinary outburst of distinctively Christian creativity — in all the arts and humanities — that occurred especially in the first half of the twentieth century, but has continued in certain forms ever since. It is a ridiculously ambitious and indefensibly wide-ranging course, since we will look (sometimes briefly, sometimes in detail) at painting, architecture, music, literature, philosophy, philosophy, and filmmaking. Basically we’ll go from G. K. Chesterton and Jacques Maritain to Marilynne Robinson, Arvo Pärt, and Terrence Malick. (Though as it happens, on Day One we’ll discuss Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil.) It’s gonna be utterly insane, and also, I think, a lot of fun. I hope to learn much in this first iteration that I can apply when I teach the course again — and I hope to teach it every year, student interest permitting.

Between that course and the Christian Spirituality one — which will go from the Didache and Maximus Confessor to Annie Dillard’s Holy the Firm — I will have on my mind, for the next few months, an vast agglomeration of works in Christian theology, philosophy, and all the arts. There will be a lot to process, and this here blog is where I do much of my processing, so — if you like that kind of thing, then this will be the kind of thing you like. If not … well, sorry about that.

Silence, Violence, and the Human Condition

I don’t believe that “silence is violence,” ever. And I doubt that anyone else would either, if they were to spend a bit of time thinking about it. People remain silent when they see violence (either threatened or performed) for a wide variety of reasons: sometimes they are indifferent to the sufferings of others, sometimes they enjoy the sufferings of others, but sometimes they have quite legitimate fears that any protest will lead to violence being inflicted upon them without anyone else being saved. Protest is not inevitably successful, and truthful accusation does not inevitably lead to arrest and conviction. Moreover, there are ways other than speech of responding to, or striving to prevent, impermissible violence.

Even when one’s silence does make it more likely that someone will be hurt, we do not benefit from erasing the distinction between sins of omission and sins of commission. Indifference to the suffering of others is a grave sin, but there are sins still graver. And different. As Auden wrote in his poem “The More Loving One,”

Looking up at the stars, I know quite well

That for all they care, I can go to hell,

But on earth indifference is the least

We have to dread from man or beast.

So, no: it is untrue that silence is violence.

Shall we say, then, that silence is complicit in violence? It’s obvious why that is a more defensible argument, but it is not as dispositive as people who use it believe. I recently wrote something about Israel and Gaza, but I didn’t do it because people told me that otherwise I would have been complicit in the violence done there – though indeed people did tell me that. I wrote it for my own reasons, not because I felt that I was complicit in anything.

There are more evil things going on in the world than any one person can respond to. You could spend all day every day on social media just declaring that you denounce X or Y or Z and never get to the end of what deserves to be denounced. If my silence about Gaza is complicit in the violence being done there, what about my silence regarding the Chinese government’s persecution of the Uighurs? Or the government of Myanmar’s persecution of the Rohingya? Or what Boko Haram has done in Nigeria? Or what multinational corporations do to destroy our environment? Or dogfighting rings? Or racism in the workplace? Or sexism in the workplace?

There are two possible responses to this problem. One is to say that I am inevitably complicit in every act of violence I do not denounce, even if it would be impossible for me to denounce all such acts. But that position leads to a despairing quietism: Why should I denounce anything if in so doing I remain guilty for leaving millions of violent acts undenounced?

The second way is better: pick your spots and pick them unapologetically. It’s perfectly fine for people to have their own causes, the causes that for whatever reason touch their hearts. We all have them, we are all moved more by some injustices than by others; not one of us is consistently concerned with all injustices, all acts of violence, nor do we have a clear system of weighting the various sufferings of the world on a scale and portioning out our attention and concern in accordance with a utilitarian calculus.

Some effective altruists, especially the so-called longtermists, try to do this, but their endeavor is full of errors. One is longtermism’s inevitably speculative character, its belief that future dangers to humanity can be predicted with sufficient reliability to guide our actions. A greater error inheres in the great unstated axiom of effective altruism: Money is the only currency of compassion. (As the Archbishop of Canterbury says in Charles Williams’s poem Taliessen through Logres, “Money is a medium of exchange.”)

The silence-is-violence crowd, to their credit, don’t think that money is the only commodity we have to spend: they think we can and must spend our words also. And they always believe they know what, in a given moment, we must spend our words on. What they never seen to realize, though, is that some words are a debased currency. As the Lord says to Job, “Who is this that darkeneth counsel by words without knowledge?” To speak “words without knowledge” is to “darken counsel,” that is, confuse the issue, mislead or confuse one’s hearers. The purpose of counsel is to illuminate a situation; one does not illuminate anything by speaking out of ignorance or mere rage.

Above all we need to acknowledge that no one — no one — operates with consistency in these matters. As David Edmonds writes in his recent biography of the philosopher Derek Parfit, Parfit refused to meet with a dying friend, Susan Hurley — a fellow philosopher who was the first woman to be elected a Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford — because he considered it more important to work on his philosophical writing. Yet Edmonds reports on several acts of generosity by Parfit, acts which also deprived him of work time. Similarly, as Julian Baggini writes in a review of Edmonds’s book,

He objected to the effective altruism movement’s Giving What We Can pledge to donate at least 10 per cent of signees’ incomes to relieve poverty, because he thought it was obvious that people could donate more. He also objected to the word “giving” for implying that this was optional, when he thought we were not morally entitled to our wealth. Yet in the years when he pursued photography as a serious hobby, he would spend thousands of pounds on a single print. Obsessed with typesetting, he offered to reimburse his publisher Oxford University Press for the extra costs of following his strict instructions, on one occasion paying £3,000 for wet proofs to check how the pages would actually come out from the plates. He also overpaid for a house by £50,000 just because he fell in love with it.

I am sure that Parfit thought of himself as a principled actor, but he certainly wasn’t: like almost all of us, he acted according to his own preferences. I’m sure that when he was kind and generous it was because that felt good to him, and I’m sure that when he declined to meet with a dying friend he declined not for philosophically defensible reasons but because he found such a meeting unpleasant.

Now, I am not suggesting that Derek Parfit should be a role model for anyone. To judge from Edmonds’s biography, he was an exceptionally unpleasant man, though Edmonds treats him not as wicked but rather as profoundly strange. I am merely pointing out that, for all his fierce labor to identify and describe the objective roots of morality, Parfit’s own behavior was as inconsistent and unprincipled as yours and mine or the Effective Altruist next door.

I think what we should learn from all this is simply that one should have principles — ideally better ones than Derek Parfit had — but we should not be ashamed of the subjectivity inherent in them. I know people who care for abandoned dogs, and whose attention to those abandoned dogs makes them effectively, if not theoretically, indifferent to matters that many people believe to be much greater concern: what’s happening in Gaza, who the next President of the United States will be, global climate change, etc. I think that’s just fine. The world has so much more suffering than any of us could possibly address that any remediation, any limiting of harm and pain and suffering, is a good thing. And we are not wired in such a way that we can maintain our commitment to undoing or preventing harm that (for whatever reason) doesn’t really touch our hearts. We should not feel guilty for failing to think about — still less for failing to speak about — climate change when there is something else, some other suffering or violence right before us that we can to some degree ameliorate. That’s the human condition and we ought to embrace it. In enables us to leave the world in at least a slightly better condition than we found it.

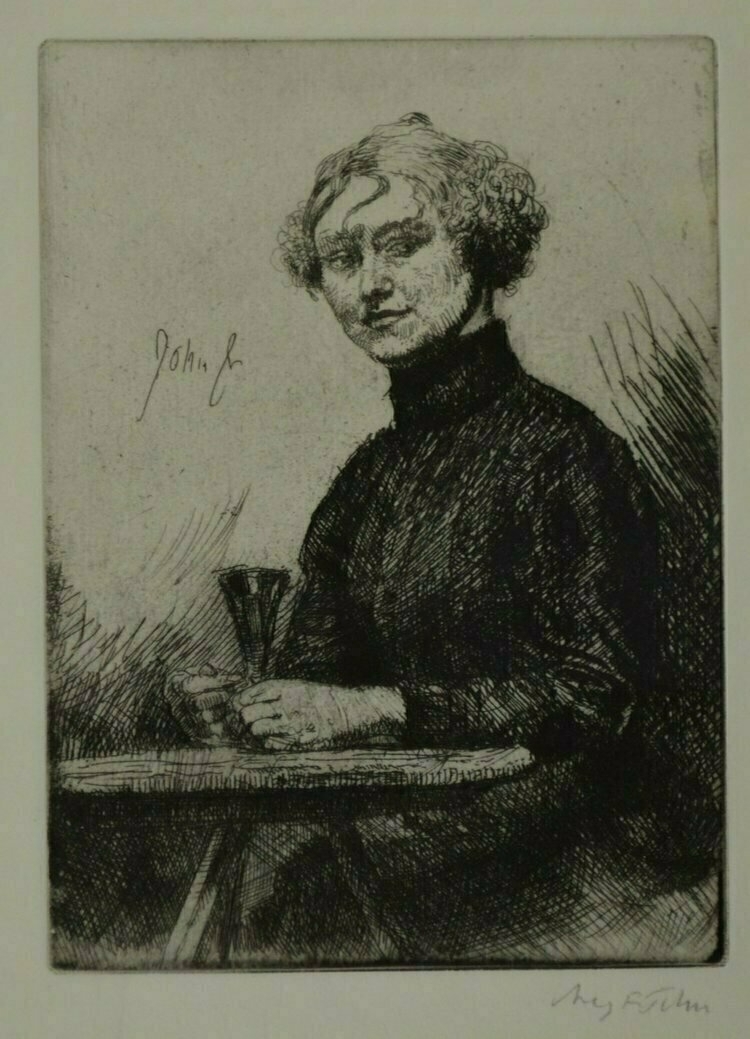

Augustus John, “A Glass of Wine” (1902)

Mary Harrington: “A culture that valorises ‘cool’ sets us up to fail as social beings - and then sells us myriad forms of ‘self-care’ to make up the shortfall. Against this, you need to be cringemaxxing. You need to be seeing old schoolfriends. You need to be helping out at Scouts. You need to be praying with old ladies, babysitting people’s kids, picking up litter, and wearing the jumper your nan knitted. It feels weird to begin with, but it’s worth it. Trust me: I’m as uncool as it gets. You need to be cringemaxxing.”

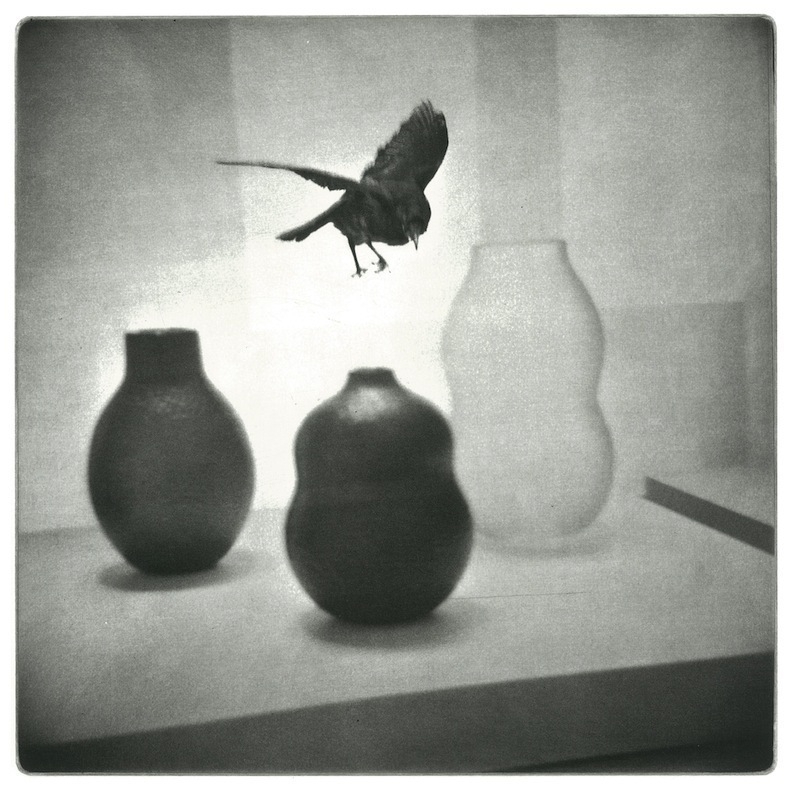

“The Arrival,” photograph by Carol Munder.

Legal Sauce for the Legal Goose

From an an interview with Jill Lepore:

I’m working on a long book about the history of attempts to amend the Constitution. And on the one hand, we have a Constitution that has a provision that allows for generativity and invention and adjustment and improvement and alteration and remedy and making amends, and all of these wonderful, beautiful ideas that we associate with the idea of the future. And yet, we live in a world where we can’t actually use that provision because our politics are so overridden with the idea of the past. Consider the Supreme Court’s history-and-tradition test, under which we can’t do anything that doesn’t derive from the past. The week that we’re speaking, the Supreme Court is hearing oral arguments on the question of whether people who have restraining orders against them due to domestic abuse can be prohibited from buying or owning weapons, and the test that the Supreme Court uses is to ask: “Was there an analogous law like that in 1787?” That is plainly nuts. In that sense, we are held hostage by the dead.

This is a mess. Lepore means not “history and tradition,” but “text, history, and tradition” (THT for short) — see e.g. this article. (THT may or may not be a coherent model of interpretation. One complication, raised by some legal hermeneuts, is whether “history” and “tradition” are always compatible: sometimes legal tradition can be shown to be indifferent to or ignorant of the relevant history. But we won’t get into that here.) In a far more important error she is confusing the THT standard of interpretation with a different one, originalism: “Was there an analogous law like that in 1787?” is not a THT question but a question about original meaning. Originalists don’t care much about how their judicial predecessors have interpreted the law. They care primarily about what the text’s original public meaning was. They think that that should be the essential interpretative canon. (Originalism can sometimes be in tension with textualism, but that’s another matter to ignore for now.)

So Lepore is writing "a long book about the history of attempts to amend the Constitution” but doesn’t have even the most elementary knowledge of the rival schools of legal interpretation. We just have to hope that she learns as she goes along.

But let’s continue by posing a hypothetical. Suppose Donald Trump becomes President again; suppose also that he has a majority in the House and Senate. In light of what he says is an unprecedented influx of dangerous illegal immigrants, Trump declares a State of Emergency and invokes the Alien Enemies Act. (That might have its own interesting legal consequences, but let’s set those aside for now.) Then Congress, with the President’s support, passes a law deeming criticism of the President’s policies in this time of Emergency a form of sedition, to be punished appropriately. The law is challenged and the Supreme Court rules that the law violates the First Amendment’s protections of freedom of the press. Some of the justices employ THT principles to articulate their case, and some of them use originalist canons, but they agree on the decision.

“That is plainly nuts,” Trump then says. “We’re being held hostage by the past. We’re looking to achieve generativity and invention and adjustment and improvement and alteration and remedy and making amends, and the Courts are getting in our way!”

And Jill Lepore would have to agree, wouldn’t she?

The answer is: No, of course she wouldn’t agree. Because, we would learn, many of the legal protections that Lepore admires, reveres, and relies on were also made in the past. Indeed, any existing law is by definition the product neither of the future nor the present but the past. If existing laws prevented her from being arrested and tried for sedition with (say) her New Yorker articles used as evidence against her, she would not feel that anyone was being “held hostage by the past,” but rather that the Founders, in making the Bill of Rights, had shown remarkable foresight, wisdom, and commitment to freedom.

So Lepore’s actual position is not “We should not be held hostage by the past,” because that would be to say that we should not have any laws. What she means is something more like this: “It should be easier for us to change the laws to get what we want.” But — the eternal question returns — who are “we”? And it’s obvious that by “we” Lepore means “people who share my politics.” Which would be fine if people who share Lepore’s politics are the only people who will ever be elected to political office in this country. But they aren’t. If we ever get a MAGA President and a MAGA Congress, and they set out to implement their vision of “generativity and invention and adjustment and improvement and alteration and remedy and making amends” — another word for “making amends” is “retribution” — then you can bet that Lepore would be one of the first people insisting that those political ambitions be forcibly restrained by law, i.e., that they be “held hostage to the past.”

I suspect that Lepore was formed in an environment in which leftish people like her wanted change, which is good, while people on the right wanted sameness, which is bad. She hasn’t adjusted her thinking to the rise of MAGA populism, which wants change as much as she does, and feels the restraint of existing law and legal interpretation as much as she does. They just want different changes than the ones she prefers. MAGAworld ain’t conservative.

Basically what I’m saying is: Jill Lepore hasn’t thought this through. She hasn’t thought it through because — here again she is like her MAGA counterparts — she lives in an intellectual monoculture. And one bad consequence of living in an intellectual monoculture is that it makes you incurious. THT, originalism, whatever, it’s all the same to people who want the same changes and don’t like having their desires thwarted.

People whose political desires are thwarted by judges are always quick to declare the legal system illegitimate. Today it’s leftists who think the Supreme Court lacks legitimacy, but in the Clinton era it was the right that felt that way — and in both cases the feeling arose directly and uncomplicatedly from disliking judicial outcomes. But there’s a lot more to the evaluation of the judiciary than looking at outcomes. It would be nice if a distinguished historian writing a book about attempts to amend the Constitution knew that.

P.S. The domestic-abuser-weapon-ownership case that Lepore mentions is United States v. Rahimi. I think that this situation should be and will be decided in the way that Lepore prefers, but if you read some of the material I’ve linked to you’ll discover why the question has made it all the way to SCOTUS. “Why is this even a thing?” is usually an exclamation rather than a question, but if you really ask you can learn a bit.

BBEdit 15, in addition to getting several interesting new features, has undergone some slight but really quite pleasant adjustments to its appearance.

Currently reading: The Spirit of Early Christian Thought by Robert Louis Wilken. This will be my third complete reading of this great book. 📚

The Mouth of Orcus, in the Gardens of Bomarzo.