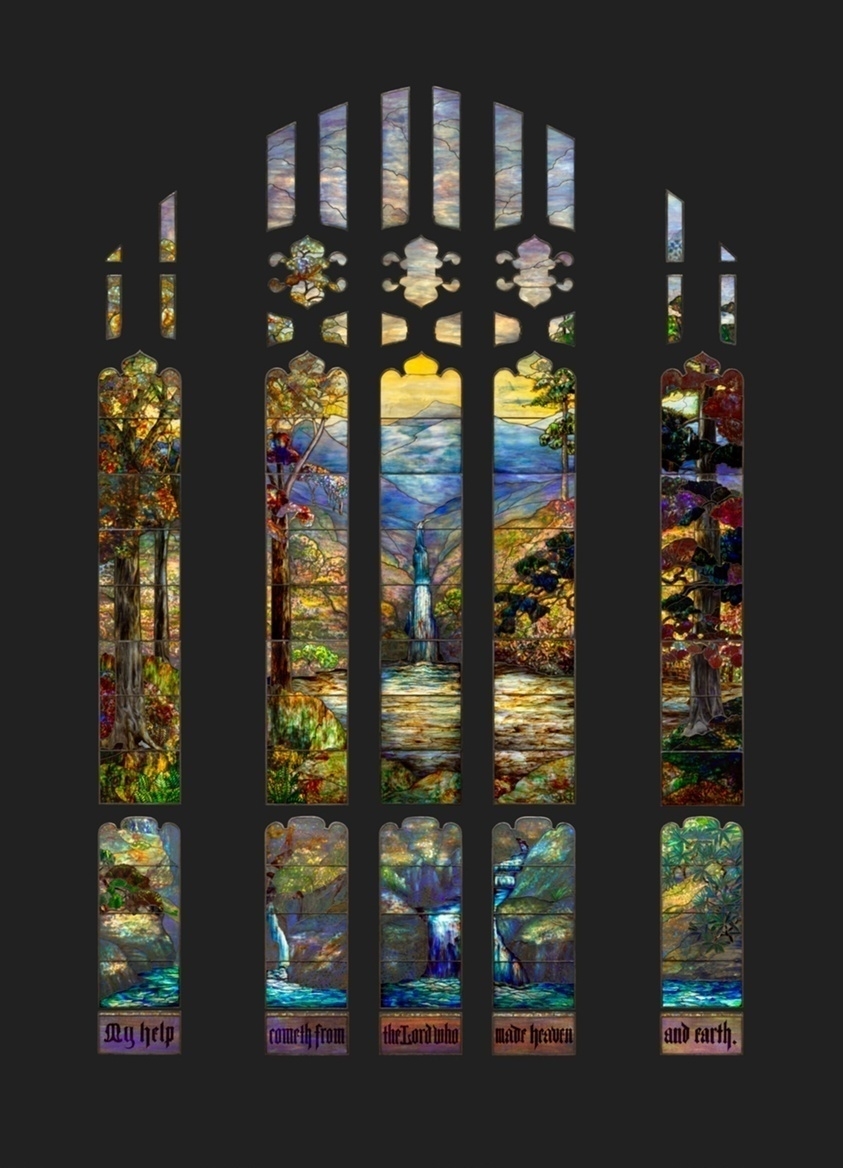

And here is a Tiffany window from a Philadephia church. It and its companion piece were saved from destruction by a man who bought them, along with othrer church furnishings, for six thousand bucks. He had no idea what he was buying: the windows were so covered with grime that they were unrecognizable.

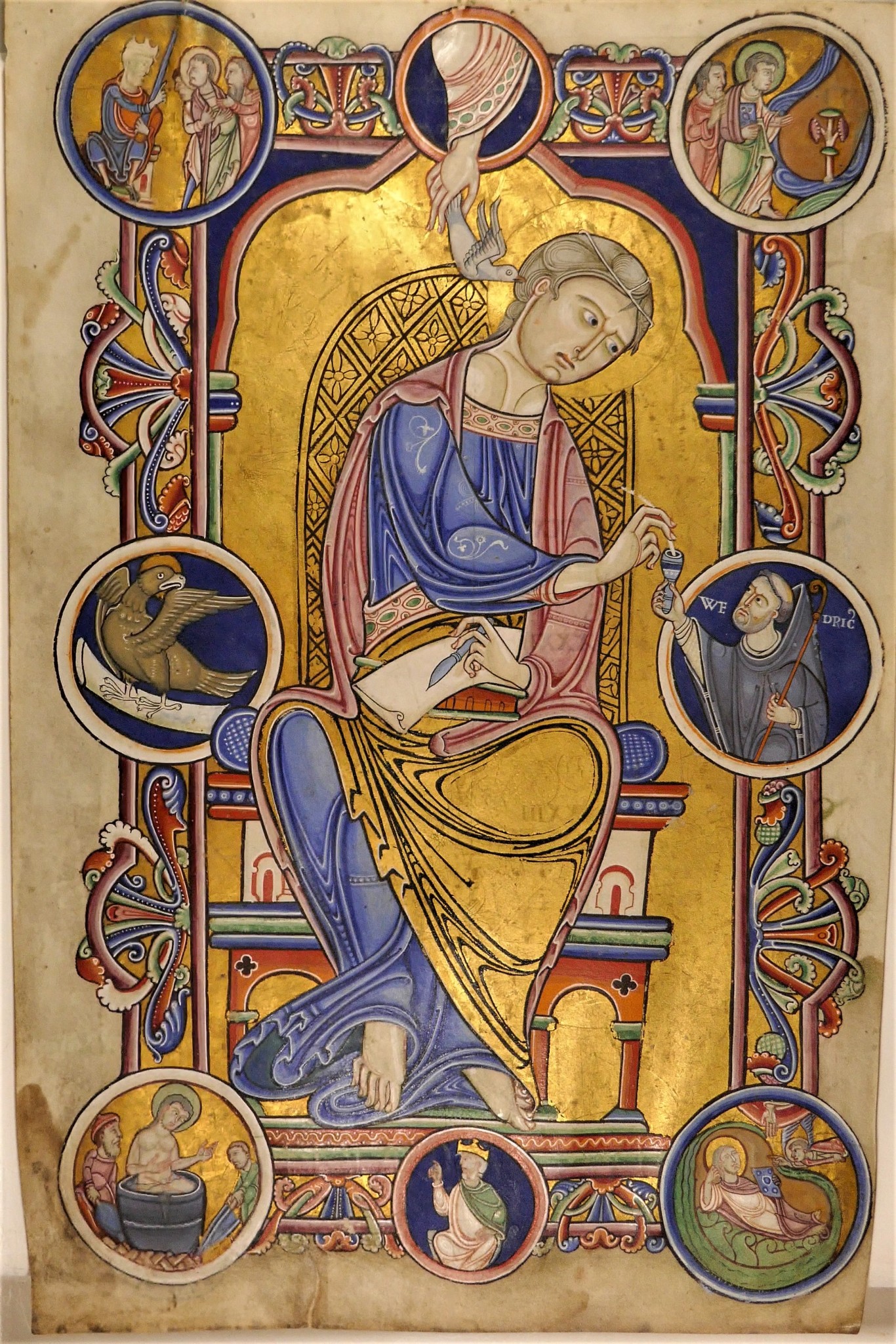

Here’s an Agnes Northrop window, this one at the Art Institute of Chicago.

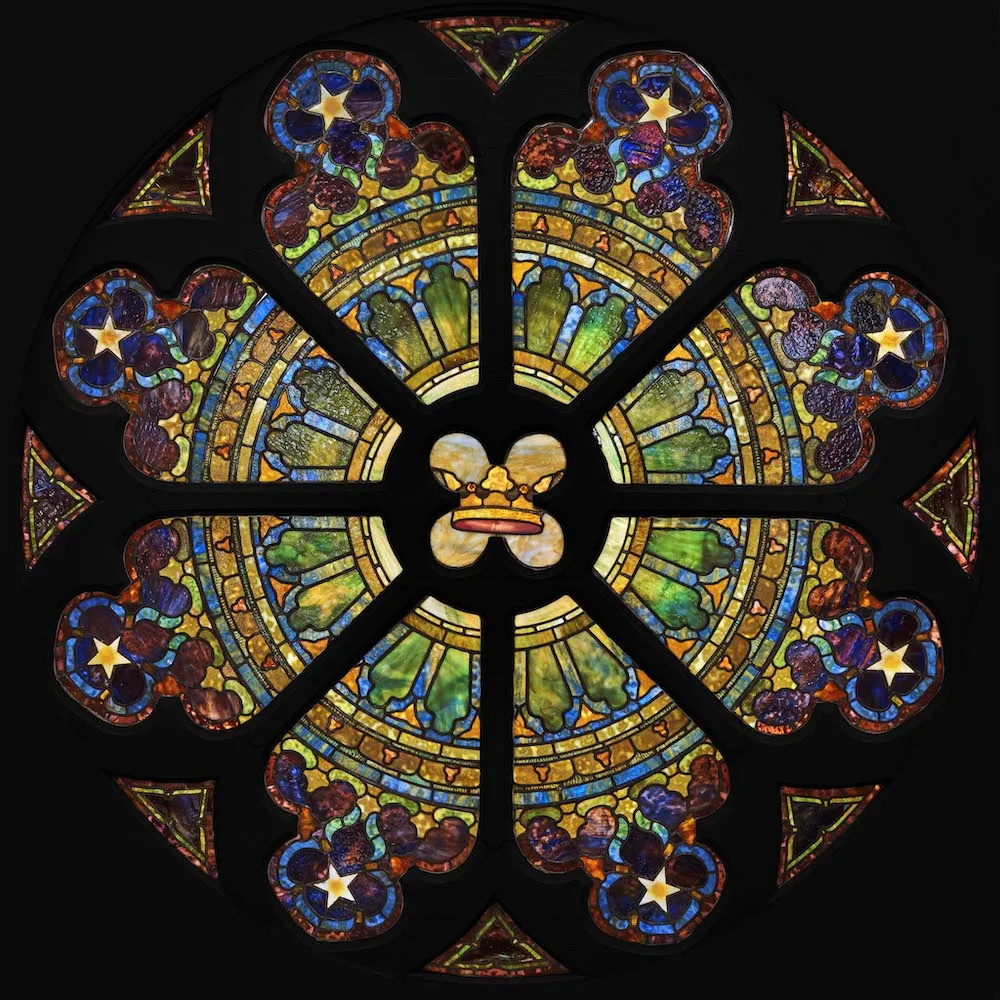

The Met has acquired “Garden Landscape,” a window made by Agnes Northrop in Lewis Comfort Tiffany’s workshop. Since the window is ten feet wide and seven feet tall, I’ll be eager to see where and how they display it.

On the last day of the year, I wrote a post on why I don’t do end-of-year posts.

Who's Counting?

I’m not doing an end-of-year roundup of what I’ve written this year, or what I’ve read, or what I’ve watched, or what I’ve listened to, or where I’ve traveled, or the museums I’ve visited, or the concerts I’ve attended – that last one because I didn’t attend any concerts in 2023, not even Taylor Swift’s Eras tour. But I’m not writing up any of that other stuff because I don’t know: don’t know how many books I’ve read, movies I’ve seen, etc. etc. I couldn’t tell you what the most-read posts on this blog are because I don’t have analytics enabled. I don’t know what my Top Ten Books of the Year are because I just don’t think that way.

I used to; when I was a teenager I kept a list of the Ten Best Books I’ve Ever Read and every time I read a book I felt obliged to sit down and think about whether it broke the top ten – and if so, where did it belong? (Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End reigned unchallenged at the top for quite some time – and then I read Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed.) But then after a few years I realized that some of the books that meant the most to me were, unaccountably, not on the list; while some books that I had put on the list … I squirmed just seeing the titles. And the whole business was so much work. I now think of the day I crumpled up the sheet and threw it in the trash as my first real step towards maturity as a reader.

But it took me a lot longer to rid myself of that year-end feeling of accountability, of the calendar-turning responsibility to make a report. Now that I’ve put all that behind me, it seems odd that I ever thought that way.

Micro.blog has a great feature called Bookshelves, which I often – though not altogether consistently – use to note what I’m reading, less for myself than for those who ask. You can note what you want to read – which I never do, because I read at whim – what you’re currently reading, and what you’ve finished reading. But there are (blessedly) no dates on that page I just linked to, only book covers. I could figure out how many of those books I read in a given year, but I never have and never will. And in any case those three categories are insufficient: something important is missing.

I am inspired by my buddy Austin Kleon’s list of the books he didn’t read this year, the idea for which, he says, he got from John Warner. Inspired not to do that, exactly, but some year – not this year, mind you – to make a list of Books I Abandoned This Year.

I think one of the most interesting things you can do as a reader is to sit down and think about why you abandon a book, when that happens to you. Many, many pages in my notebooks discuss just this question. Over the years I gradually came to an awareness: the kinds of book I am most likely to abandon are history and theology; the kinds I am least likely to abandon are novels and biographies. It turns out that while I am deeply interested in both history and theology, my mind needs a human story to hook itself to. (Thus the great narrative historians, like Gibbon and C. V. Wedgwood, command my attention in precisely the same way that novels and biographies do.) Novels and biographies raise certain questions for me that I pursue by mining works of history and theology for information and insight, which means that I read quite a bit of history and theology; I just don’t read those books from beginning to end. I don’t read them the way I read narratives.

If you ask yourself why you’re abandoning a book you can learn a lot about your own intellectual habits, preferences, needs. The books you don’t finish can be even more important to you than the ones you do, if you learn to inquire into your own responses. And that’s one reason why I don’t make these year-end lists: they tell a misleading story.

And I’ve only noted one of the ways they mislead: What about short stories and poems and essays and even blog posts? In any given year, those short-form genres may shape your thoughts and feelings, may contribute to your flourishing, more than any work that happens to be book-length. One of Pascal’s pensées or one Psalm may matter more than a dozen books.

A few years ago, I started the practice of taking one hour each week to reflect on what I read and wrote in the previous seven days; and one morning each month to reflect on what I read and wrote in the previous month. I think that has been infinitely better for my intellectual and spiritual orientation than any year-end list could be. Something to consider, maybe?

A blessed new year to you, to me, and to this poor wounded world.

Finished reading: The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn. A lovely novel, at once melancholy and hopeful, about learning to cope with a changed world, and about the many forms and meanings of family. 📚

Much of the social energy of the old internet has now retreated underground to the cozyweb. Except for a few old-fashioned blogs like this one, there’s not much of it left above-ground now. But there’s an odd sort of romance to holding down a public WordPress-based fortress in the grimdark bleakness, even as almost everything (including the bulk of what I do) retreats to various substacks, discords, and such.

Amen to that. Though I really do believe that there will be a slow and perhaps not readily noticeable renewal of blogging. I’m keeping my eyes peeled. See the “blogging” tag at the bottom of this post for more thoughts along these lines.

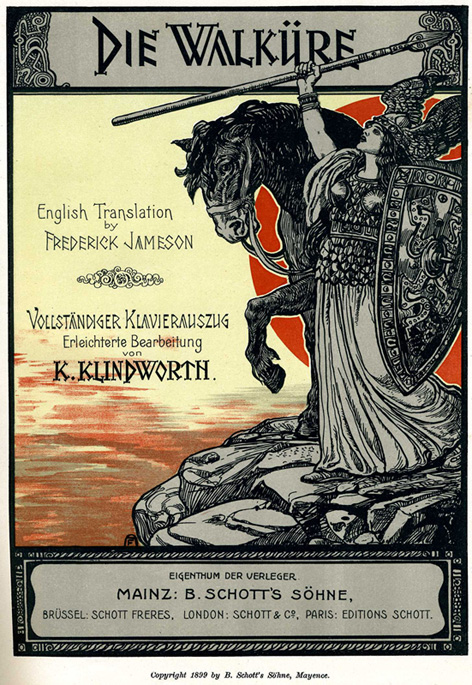

on Wagner

As part of my ongoing project to understand myth and mythmaking in the modern era I have been sitting down to a full encounter with Wagner’s Ring cycle — which I’ve never before listened to completely and in sequence. I’m doing this by listening to the legendary Georg Solti Decca recording and following along with the excellent Penguin Classics bilingual edition of the libretto. I have some reservations about John Deathridge’s translation, but fortunately my German is (barely) good enough that I can make it through without only occasional consultations of the English version. (I’ve got the beautiful hardcover edition, which I think may have been printed only in the U.K.)

I’m not finished yet but I have gotten far enough along to say with some confidence that Wagner’s celebrants who think him a nearly incomparable genius are absolutely correct, and Wagner’s detractors who think him unforgivably self-indulgent are also correct. And I’ve also come to some conclusions about why both of these things are true. (Probably many other people have come to the same conclusions, but I have read very little Wagner criticism, with one major exception noted below.)

Again, I am not fluent in German but anyone with even minimal competence in the language can see how brilliant a poet Wagner is, and especially how skillfully he employs alliteration and assonance to create his effects — and with a remarkable economy of language. Nietzsche’s inclination to compare Wagner as poet only with Goethe is remarkable but not utterly extravagant.

But in a way Wagner’s greatness as a poet is a problem — or perhaps I should say that it became a problem when he made the fateful decision to write the entire libretto before composing a single note of music. Why was that decision so fateful? Because Wagner knew he was a great poet. He knew that he had written magnificent poetry and he didn’t want to sacrifice any of it once he got to the stage of musical composition

That isn’t that big of a problem in Das Rheingold, which in fact moves with remarkable fluidity and pace: it has almost none of the longeurs that the later dramas in the cycle suffer from. The difficulties kick in with the first act of Die Walküre. If you haven’t heard this work … well, imagine something like the Prologue to Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, except instead of lasting six minutes it lasts more than an hour. More than an hour of pure exposition, in which characters — well, mainly one character, Siegmund, tells us his entire history. C. S. Lewis (famously) wrote that the final books of Paradise Lost, in which the archangel Michael tells Adam of the future of humanity, is an “untransmuted lump of futurity”; likewise, the first act of Die Walküre is an untransmuted lump of historicity, with only occasional orchestral coloration to enliven matters.

Wagner trusts overmuch in the power of his own verse, or is simply overly attached to it — which is a reminder that often it’s good to divide the labor of the librettist and the poet. When Auden was writing his Christmas oratorio, For the Time Being, he did so hoping that his friend Benjamin Britten would set it to music. But when he gave to Britten the magnificent fugal chorus on Caesar he had written, Britten couldn’t help laughing. He told Auden that if he wanted an actual fugue to be written, and a figure that would set a single scene in an oratorio with many scenes, then he should have written three lines, not seventy. So Auden kept the poem as written and gave up on the idea of having it set to music. By contrast, Wagner never had anyone to remind him of the necessary constraints; so he ignored them.

And there’s another problem as well. Recently I read Walter Murch’s famous meditation on film editing, In the Blink of an Eye, and was taken by his articulation of one of his chief rules: “You want to do only what is necessary to engage the imagination of the audience — suggestion is always more effective than exposition.” It’s interesting that Wagner understands this principle so well in his music, which often is rich and deep with suggestion, without understanding it at all in his writing. Exposition often dominates. I think his addiction to detailed exposition has something to do with his belief in himself as a sage and a mythographer.

I may have more to say as I move through this extraordinary work of art — though maybe not, because the experience is tiring. Right now I feel about it much as Virginia Woolf felt about Joyce’s Ulysses, which she called "a memorable catastrophe — immense in daring, terrific in disaster.” But it fascinates me as a myth, especially as a humanist myth — a myth about the ending of the gods and what Bonhoeffer would later call the “coming of age” of humanity. I think that is why Roger Scruton — a man convinced of the absolute necessity of religion to humans but without any firm faith in Christianity — loves the Ring cycle so much. His book about it is magnificent, I think, but also somewhat depressing, because as a Christian I certainly don’t think that a humanist myth has the power to sustain us. But Wagner put an enormous charge into his effort to make it do so.

Francis Spufford on picking through the ruins of Christendom:

Those of us who, despite everything, think there’s something precious in the words jumbled-up now among the rubble, do not do so because we are pro-tyranny or anti-self discovery. We do so because we know that what was written on those towering walls wasn’t the credo of an authoritarian certainty at all. But instead — mixed up, yeah, with some heterogenous other stuff over the centuries, some questionable — a song of liberation, a startling declaration that power, that love, that justice, that order, that God the creator of all things, weren’t what we thought they were, but came closest to us in paradoxes. Wisdom, in foolishness; strength, in weakness; sovereignty over the immense empire of matter, in helpless self-sacrifice, in a choking man brought to death by a shrugging government. What’s written on the bricks still has the power to shock, when you join them together. GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS turns out to lead to, THAN THAT HE LAY DOWN HIS LIFE FOR HIS FRIEND. Not very positive, is it? LOVE YOUR EN- continues, -EMY, AND PRAY FOR THOSE WHO PERSECUTE YOU. What’s that about? How will that help me to be thinner, richer, stronger, more sexually successful? It won’t. It will only help you to be kinder, braver, more tolerant of our inevitable imperfections, and more hopeful; more convinced that the worst than can happen to us, as humans, is not the last word, because there is a love we should try to copy in our small ways, which never rests, never gives up, is never defeated.

Man, Moon, Book

My family gave me a wonderful Christmas present: the Folio Society edition of Andrew Chaikin’s A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. In chronological terms, Chaikin’s book basically picks up where Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff left off, but Chaikin is the anti-Wolfe: restrained and businesslike, rather than flamboyant and hilarious. Still, he tells the story well, and this edition is magnificently complemented by dozens and dozens of perfectly-chosen photographs. What a delight.

And, like many Folio Society editions — I have about a dozen of them — this book prompts me to reflect on what an extraordinary thing a book can be. When a book is well-written, well-edited, well-designed, well-printed and bound, so many skills have been practiced at a high level, from journalistic research to paper-making to photographic reproduction, that it amounts to a genuine Gesamtkunstwerk. To me, few things are as beautiful as a beautiful book.

Also, you have to love the fact that the book’s text is set in Adrian Frutiger’s Apollo, with Futura for display.

Stefan Collini: “Carlyle’s forte as a social critic was not likely to lie in making practical suggestions. The denunciatory sublime was his preferred register.” I shall make a point of using the phrase “denunciatory sublime” in future.

NYT: ”Despite these difficulties, there can be a reluctance among the clergy to talk about their own troubles. Ministry is often seen as a calling rather than a vocation, let alone just a job, and the concept of service underwrites the work.” Pro tip: Look up the etymology of the word “vocation.”

the good earth

Fifty-five years ago, on Christmas Eve 1968, astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders were orbiting the moon. It was while in lunar orbit that Anders took the photograph above. Later he would say that the irony of their mission, for him, was that they went to explore the moon but ended by discovering the Earth.

On that Christmas Eve the three astronauts made a transmission to their home world, which began with a reading, done in turns:

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.

And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.

And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so.

And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day.

And God said, Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so.

And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called he Seas: and God saw that it was good.

Then, the reading concluded, Frank Borman said this: “And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.”

The good Earth.

When I think of that phrase, and the enormous load of meaning it bears, I remember something John Ruskin wrote:

God has lent us the earth for our life; it is a great entail. It belongs as much to those who are to come after us, and whose names are already written in the book of creation, as to us; and we have no right, by anything that we do or neglect, to involve them in unnecessary penalties, or deprive them of benefits which it was in our power to bequeath. And this the more, because it is one of the appointed conditions of the labor of men that, in proportion to the time between the seed-sowing and the harvest, is the fulness of the fruit; and that generally, therefore, the farther off we place our aim, and the less we desire to be ourselves the witnesses of what we have labored for, the more wide and rich will be the measure of our success. Men cannot benefit those that are with them as they can benefit those who come after them; and of all the pulpits from which human voice is ever sent forth, there is none from which it reaches so far as from the grave.