Simple snapshot of a totally ordinary sight.

Chris Beha: “I sometimes think that the modern world’s true cultural divide is not between believers and unbelievers but between those who think life is a puzzle that is capable of being solved and those who believe it’s a mystery that ought to be approached by way of silence and humility. I am a problem solver by disposition, but in my heart I am strongly on the side of the mysterians.”

The Reason for the Season.

Just learned from my buddy Austin Kleon about Mishka Westell’s art.

An extraordinary story on how redwoods survive fire.

exam time!

I often give my students take-home exams that ask them to explicate (give a close reading of) passages from books we are reading. They are asked to identify the passage, place it within the context of the work it is taken from, and then explain what it’s doing. It’s an old-fashioned kind of assignment, hearkening back to the days of the New Criticism, but the emphasis in Baylor’s Great Texts program, like that of the University of Chicago programs on which it is based, is on careful reading of primary texts; and even if this were not so, there’s a lot to be said in this ideological age — an age in which people believe the point of a university is to provide a venue for the declaiming of positions you already hold — there’s great value in requiring students to dig into the details of one small chunk of text and really read it.

Here are the texts for an exam I’ve just handed out.

PASSAGE 1

Each step in the development of the bourgeoisie was accompanied by a corresponding political advance of that class. An oppressed class under the sway of the feudal nobility, an armed and self-governing association in the medieval commune: here independent urban republic (as in Italy and Germany); there taxable “third estate” of the monarchy (as in France); afterwards, in the period of manufacturing proper, serving either the semi-feudal or the absolute monarchy as a counterpoise against the nobility, and, in fact, cornerstone of the great monarchies in general, the bourgeoisie has at last, since the establishment of Modern Industry and of the world market, conquered for itself, in the modern representative State, exclusive political sway. The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.

The bourgeoisie, historically, has played a most revolutionary part.

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his “natural superiors”, and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment”. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom — Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.

PASSAGE 2

— The slave revolt in morals begins when ressentiment itself becomes creative and ordains values: the ressentiment of creatures to whom the real reaction, that of the deed, is denied and who find compensation in an imaginary revenge. While all noble morality grows from a triumphant affirmation of itself, slave morality from the outset says no to an ‘outside’, to an ‘other’, to a ‘non-self: and this no is its creative act. The reversal of the evaluating gaze — this necessary orientation outwards rather than inwards to the self — belongs characteristically to ressentiment. In order to exist at all, slave morality from the outset always needs an opposing, outer world; in physiological terms, it needs external stimuli in order to act — its action is fundamentally reaction. The opposite is the case with the aristocratic mode of evaluation: this acts and grows spontaneously, it only seeks out its antithesis in order to affirm itself more thankfully and more joyfully. Its negative concept, ‘low’, ‘common’, ‘bad’, is only a derived, pale contrast to its positive basic concept which is thoroughly steeped in life and passion — ‘we the noble, we the good, we the beautiful, we the happy ones!’ If the aristocratic mode of evaluation errs and sins against reality, this happens in relation to the sphere with which it is not sufficiently familiar, and against real knowledge of which it stubbornly defends itself: it misjudges on occasion the sphere it despises — that of the common man, of the lower people.

PASSAGE 3

You see: reason, gentlemen, is a fine thing, that is unquestionable, but reason is only reason and satisfies only man's reasoning capacity, while wanting is a manifestation of the whole of life — that is, the whole of human life, including reason and various little itches. And though our life in this manifestation often turns out to be a bit of trash, still it is life and not just the extraction of a square root. I, for example, quite naturally want to live so as to satisfy my whole capacity for living, and not so as to satisfy just my reasoning capacity alone, which is some twentieth part of my whole capacity for living. What does reason know? Reason knows only what it has managed to learn (some things, perhaps, it will never learn; this is no consolation, but why not say it anyway?), while human nature acts as an entire whole, with everything that is in it, consciously and unconsciously, and though it lies, still it lives. I suspect, gentlemen, that you are looking at me with pity; you repeat to me that an enlightened and developed man, such, in short, as the future man will be, simply cannot knowingly want anything unprofitable for himself, that this is mathematics. I agree completely, it is indeed mathematics. But I repeat to you for the hundredth time, there is only one case, one only, when man may purposely, consciously wish for himself even the harmful, the stupid, even what is stupidest of all: namely, so as to have the right to wish for himself even what is stupidest of all and not be bound by an obligation to wish for himself only what is intelligent.

self-repair

[caption id="" align=“aligncenter” width=“600”] Michael Torevell, News of Great Joy, mixed media and digital painting, 2022 [/caption]

Michael Torevell, News of Great Joy, mixed media and digital painting, 2022 [/caption]

The basic form of the sin from which we need to be delivered is the myth of self-sufficiency. The diabolical urge that destroys our well-being again and again is the temptation to think of ourselves as somehow able to set our own agenda in isolation, and the greatest and most toxic paradox that results is that we become isolated from our own selves. We don’t and can’t know what we are as participants in the symphonic whole, and so we block off or screen out the life we need to receive, refusing to share the life we need to give. We live shrunken, hectic, short-term lives, stuck in futile conflicts and vacuous rivalries. We refine our skill at identifying other human lives, as well as the entire nonhuman environment, as competitors for space, forces that will, left to themselves, diminish rather than enrich us. We need to be healed from this habitual screening-out.This Plough issue on Repair is really wonderful. I expect I will post on other essays from it.This means that the “repair” involved in Christ’s coming in flesh is a repair of our relation to ourselves.

Annie Soudain, Winter Glow, reduction lino print, 2017, appearing with this wonderful essay by Adam Nicolson.

brokenism

“Everything is Broken,” Alana Newhouse wrote in an essay that I see quoted all the time. But of course when you look into the essay and into other essays that quote it approvingly, you come to understand that by “everything” they don’t mean everything, and by “broken” they don’t mean broken. They mean something like “Our dominant political and cultural institutions don’t function nearly as well as they should.” But that doesn’t sound as interesting, does it? “Everything is broken” is not a defined claim; still less is it an argument. It’s a cry of frustration.

I’ve decided that the social media landscape is irredeemable, but this new project by my old internet friend Erin Kissane — Erin is an absolute treasure — and Darius Kazemi is allowing me to see a tiny ray of hope.

Matthew Crawford on a broken tail light that cost $5600 to repair:

On this particular luxury pickup truck, moisture in the tail light caused the usual corrosion, making resistance on the circuit go out of range. This circuit is in communication with many other circuits, so electrical gremlins propagated (probably reading as ground faults) and eventually the truck was completely dead. At this stage, identifying the root cause of the breakdown was no trivial task. But most of the $5,600 charge for getting the truck running was for parts confined to the tail-light housing, not the diagnostic and parts-swapping labor. Commenting on this case, another YouTube mechanic named Uncle Tony points out that salvage yards are full of recent model cars that are in great shape — mechanically sound and rust-free, with good interiors and good paint — but underwater on repair costs due to electronic complexity.

Presumably the carmakers want us to realize that (a) we can’t repair our cars ourselves, (b) can’t afford to have them repair our cars, and (c) therefore must buy a new car from them — just because of a broken tail light.

I’m gonna do my best to keep my 10-year-old car for another ten years.

Campus lookin’ real purty today.

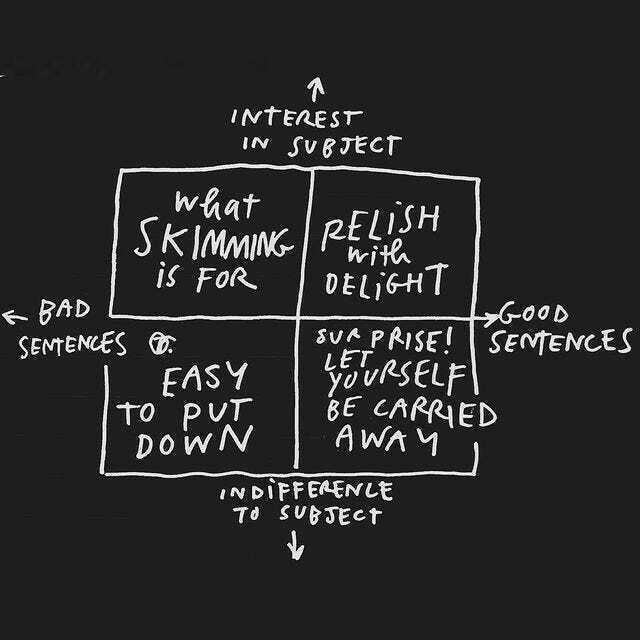

Austin Kleon’s new post on reading is fantastic. I will have things to say about it when I can clear a little time. I think if I could only subscribe to one Substack it would be Austin’s.

This collection of links by Michael Tsai raises the question: Do I actually own anything I have “bought” digitally? Books, movies, TV shows, games — can I be confident that any of it won’t eventually disappear?

Future Mann

I don’t know how many people read my recent series of posts on Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers — but then, I don’t know how many people read any of my posts, because I don’t have analytics enabled on this site. I always write under the assumption that I have somewhere between 40 and 50 readers. Anyway, I have been reading much more by and about Thomas Mann, focusing especially on the decade he lived in America — the 1940s, more or less — and have been fascinated by the ways that that period of Mann’s life, and what he wrote and spoke in those years, connects with the major themes of my own writing. So I will be returning to Herr Mann.

But not immediately. I have classes to finish, and then between now and the end of January I’ll be trying to finish a draft of my “biography” of Paradise Lost. So I’ll be setting aside my work on Mann in the interests of Getting Things Done, and in the coming weeks blogging will be inconsistent and desultory, though there will be, as always, a drizzle of links and images at my micro.blog page.