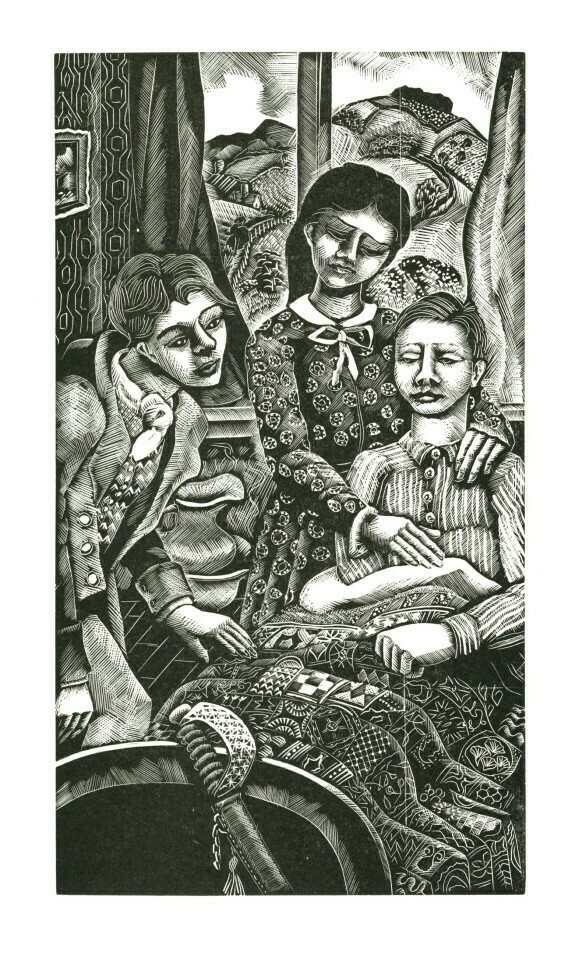

Beautiful engravings by Rachel Reckitt, for a never-published edition of The Mill on the Floss.

Hopewell Cemetery (1831), near Ashville, Alabama.

I wrote about The Devils’ Citadel (focusing largely on Humphrey Jennings), and now here’s The Devils’ Citadel Extended (focusing largely on John Ruskin).

A useful mental exercise: when people say “AI isn’t going anywhere” or “AI is here to stay,” substitute for “AI” the word “cancer.” A great many things that are here to stay are really bad and should be resisted as energetically as possible. Maybe AI isn't as bad as many fear. But the not-going-anywhere assertion is a way to avoid asking the key questions.

UPDATE: Just after posting this, I saw a review by Brad East of a new book celebrating online worship, and what does the author of the book say? “Church online is here to stay.” Of course he does. But this is even less defensible than “AI is here to stay,” because while it would be very difficult if not impossible to shut down the AI companies, any church can stop offering online worship at any time.

Note that I am not saying that online services are bad. My own parish church offers many online services, and I am not (yet) convinced that it’s as bad a thing as Brad says it is. (But “almost thou persuadest me….”) I am just decrying an all-too-common rhetoric that tries to invoke inevitability as a way of foreclosing debate before it gets started.

Whether on Twitter or Bluesky, nobody learns anything.

I have two words for the administration of Ohio State University: sales resistance.

It’s an odd thing to say about the figure of Jesus in the Gospels, but I’ve always been struck by it — from time to time there’s a deep impatience in Jesus: How can I make this clear to you? You’re an unfaithful generation. He bursts out in exasperation at the disciples. Do you understand nothing? Even in exasperation of the crowds. Jesus said: You’re all looking for miracles.

In a strange way, I feel that’s a rather compelling aspect of the story of Jesus. There’s more going on in him than he can express, and sometimes it kind of bursts out. And when I think of what the divinity of Jesus means in that context, one of the signs of it is that feeling he’s got more to say than human language can carry. As he says in St. John’s Gospel, “I have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now.”

And it’s almost as if Jesus goes to the cross saying: The only way of telling you what the love of God is like is to absorb this monumental violent injustice and show you that God is not crushed by it.

The whole conversation (with Pete Wehner) is fantastic.

Terry Eagleton's tribute to Alasdair MacIntyre is the best I've read so far:

All this makes MacIntyre one of the great moral philosophers of the 20th century. He was a radical Scottish puritan, austere and high-minded, who ended up supporting the revival of monasticism and switched his sympathies from the Bolsheviks to St Benedict. His dissent from the priorities of the modern age took an incongruous variety of forms but remained wholly self-consistent. If he turned back to Aristotle and Aquinas, it was in order to move beyond what he saw as the scepticism and subjectivism of the present. His work showed up the limits of rationalism, but was deeply averse to the irrational. It could win praise from both Leftists and conservatives, but gave no comfort to neoliberalism. MacIntyre refused to subscribe to the view that the individual was at the centre of the universe; that reason is timeless and independent of practical social life; and that relations are primarily contractual and actions chiefly instrumental. In contrast with a mean-spirited utilitarianism, he saw society not as a means of individual self-promotion but as a good in itself. He was interested in practices like playing chess or writing poetry whose goods, as he would say, were “internal” to themselves rather than external goals to be pursued.

While Wes and I are on the road, Teri is sending us Angus updates.

This post by Ed Simon marking the 150th anniversary of Thomas Mann’s birth reminds me that I have some pretty interesting posts — if I do say so myself — on Mann at my big blog.

Several replies to my newsletter wanting — perhaps demanding is the word — pictures of Angus. Your wish is my command.

I wrote a longish essay on the “total action” of the detective story — and what obligations the author of such a story has (or doesn’t have) to it.

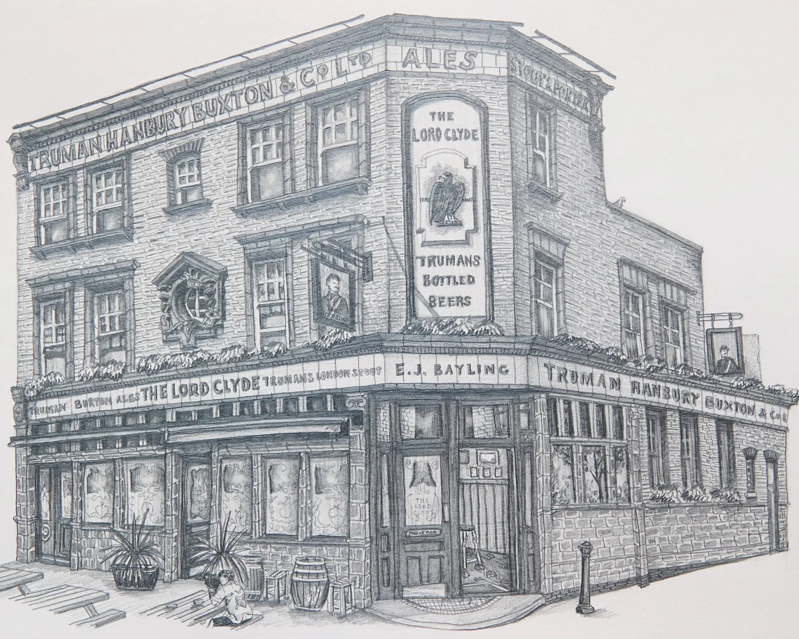

When Busman’s Honeymoon, the play co-written by Sayers and Muriel St Clare Byrne, opened in London it did so at the Comedy Theatre … which reminds me that decades later that venue would stage many Harold Pinter plays, and Pinter became its major patron. After a while he started hinting that the place should change its name to the Pinter Theatre. When management resisted, Tom Stoppard wrote to Pinter with a suggestion for resolving the impasse: “Have you considered changing your name to Harold Comedy?” (Lo and behold, the name was changed to the Harold Pinter Theatre, but only after the poor man’s death.)

Sometime in September 1935 Sayers finished Gaudy Night and sent it to her publisher, Gollancz. Victor Gollancz wired Sayers on 26 September to say that he very much liked the book. It was immediately copyedited, typeset, and printed, and hit the bookstores on 4 November. To any writer today that sounds impossible: Surely it was published in November 1936?? Nope: it went from submission to publication in little over a month.

In late 1936 the publishers Hodder & Stoughton asked Dorothy L. Sayers to complete the novel Dickens left unfinished at his death, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Sayers firmly declined, saying “nothing could induce” her to try that. But of the many people who have completed the novel, none of them were as well-suited to the task she she was. I regret her decision.

This week has turned out to be more complicated than I thought it would be, so I won’t be able to do my audio posts on Paradise Lost. But I have something better: the brilliant essays written some years ago by my friend Jessica Martin — in fact, I believe I got to know Jessica and her husband Francis Spufford through these essays, which I praised when I first read them — to introduce new readers to the poem:

Reading this series was what got me thinking about writing a book on Paradise Lost, which I had already been teaching for decades.