The Attentive Reader

Recently I gave a talk at Vassar College for a meeting of LACOL, the Liberal Arts Consortium for Online Learning. Rather than writing out a lecture, I talked my way through the slides below. I’ve added some commentary so you can get a sense of what I talked about. This isn’t exact, but it’s the general picture.

I want to begin by talking about…

The person who has done the most to help us think about these matters is Katherine Hayles:

— who wrote in 2007 about two fundamentally different modes of attention.

This kind of attention has often been represented in art, and interestingly enough, more often than not women are the ones manifesting this attentiveness. This may be related to the association of deep attention and women alike with private spaces, as opposed to the public realm traditionally governed by men.

Our great documentarian of this kind of attention is the photographer André Kertész, whom we’ll return to soon.

But perfectly private spaces are not always available, and this requires the cultivation of certain sophisticated cognitive strategies for enabling deep attention. Dennis Marsden, an English sociologist who grew up in a rather impoverished home in the north of that country, tells the story:

Here’s a photograph by Kertész that seems to be visualizing for us Marsden’s cone of silence: note the hat pulled down over the reader’s forehead, the book pulled close to the face, and rest of the world apparently excluded from whatever is going on in that circle with a radius of about a foot.

To this mode of attention Hayles contrasts its opposite:

Hearing this description, we might think of something like this:

Which reminds me of something … what could it be? … Ah yes:

The resemblance is indeed quite close:

This masterful reader sitting at the center of his informational web certainly cuts a very different figure that the reader “lost in a book”):

So here are Katherine Hayles’s two master modes of attention:

To which she attaches (especially in her recent book How We Think, shown earlier, that develops the key ideas from her 2007 article) two corresponding ways of reading:

She then adds, in light of the work of Franco Moretti and others, a third category:

But we’re going to set machine reading aside today, having paused to note its existence — it’s important, but not germane to the topic of the day.

Having outlined Hayles’s basic distinctions, I now want to adapt and extend them. I think there’s a problem with the binarity of Hayles’s typology, and I want to suggest a more complex one in which we create not an opposition but a continuum:

If we look at things this way, we can see that hyper attention and deep attention have something interesting in common: they enable what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi famously calls flow, a total absorption of the whole person in a task.

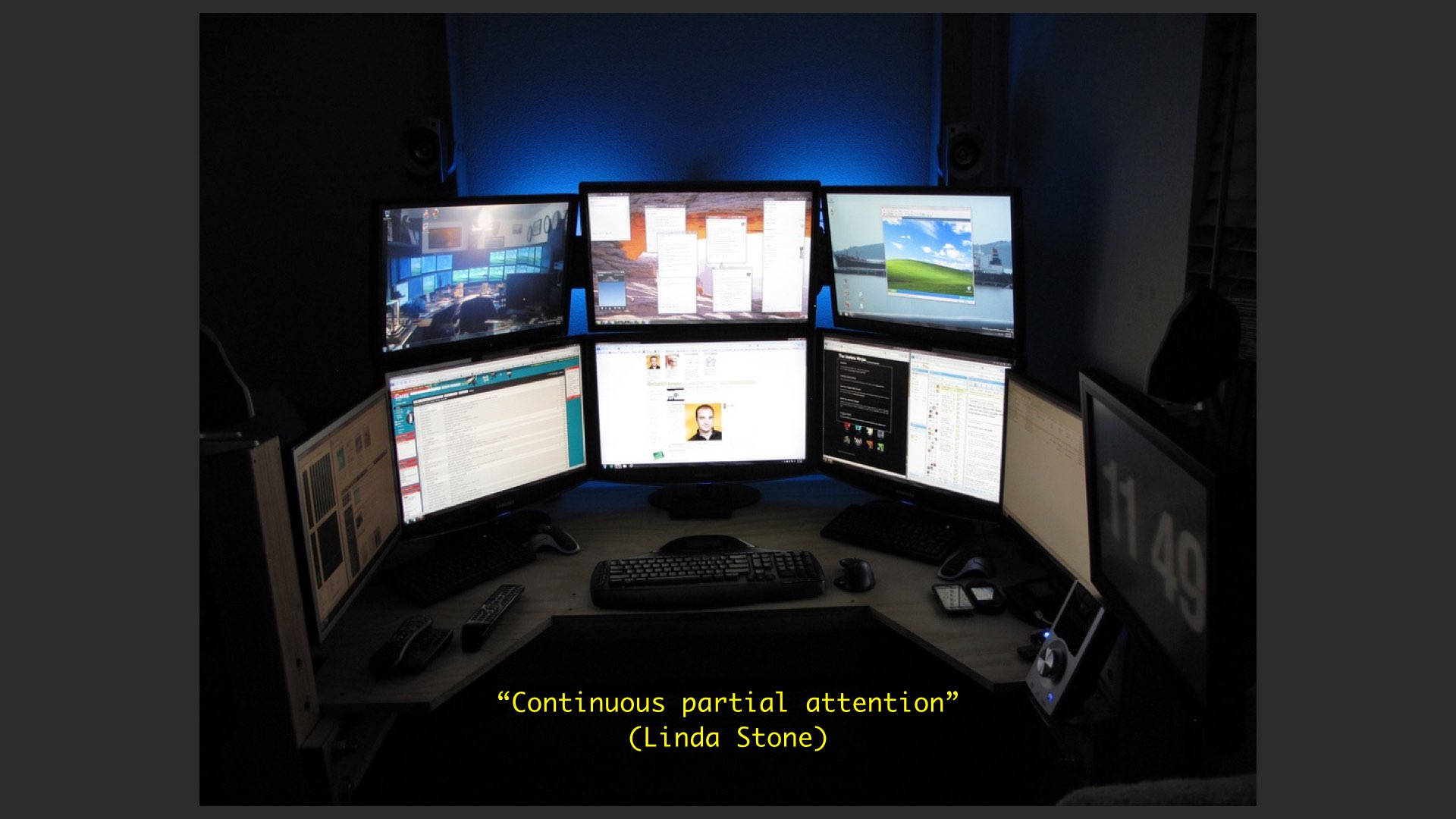

And if truly deep attention and truly hyper attention are characterized by flow, then maybe this —

— isn’t a form of hyper attention at all, but was named more accurately some years ago by Linda Stone:

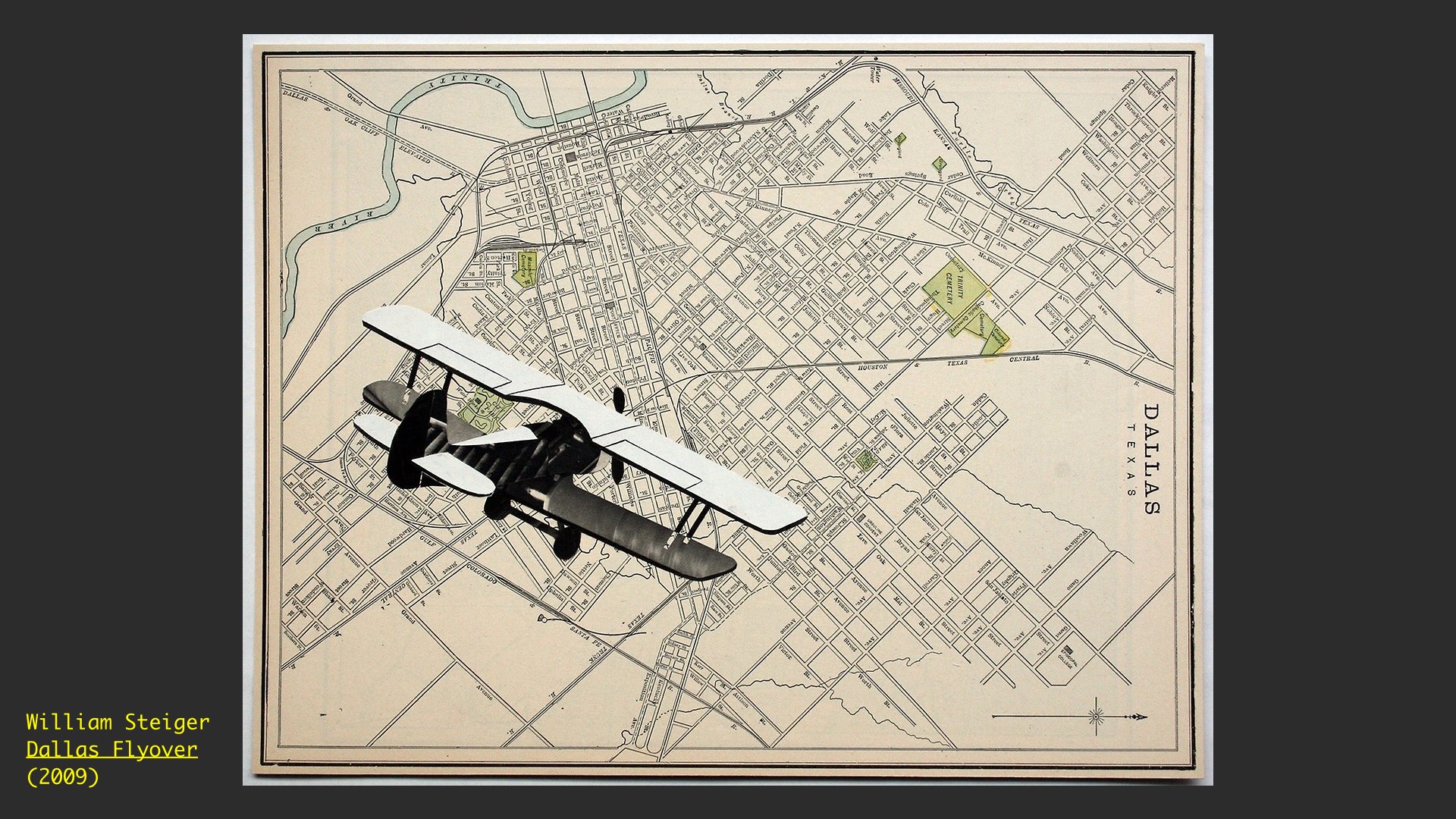

True hyper attention might look something more like this:

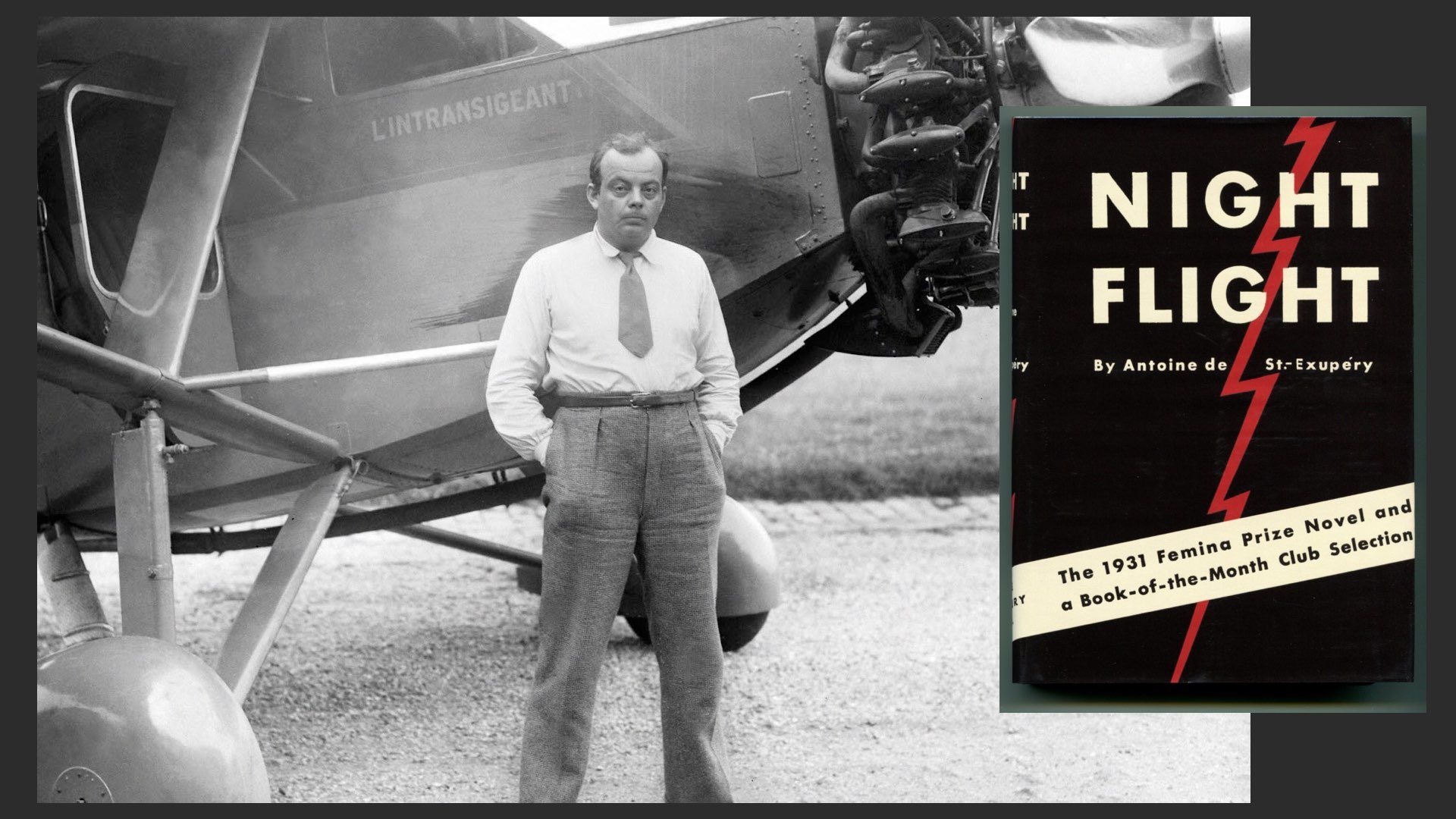

The addictive nature of early (largely pre-instrumental) flight, with the wide range of cognitive and physical demands it made — arms and legs moving in rhythm, eyes scanning the horizon, even the sense of smell engaged to note the changes in humidity that can betoken changes in air turbulence — is an ongoing theme of the romantic literature of pilots:

And if we want a contemporary equivalent of hyper-attentive flow, well, it might look something like this — yet another enterprise that calls for the aptly-named “joystick”:

Okay, so much for modes of attention. Now on to…

When we talk about these environments, there’s a word that turns up regularly.

I don’t think it’s a very good word. Too vague, comprising too many highly varied types of environment.

Let’s once more try a continuum instead of a binary:

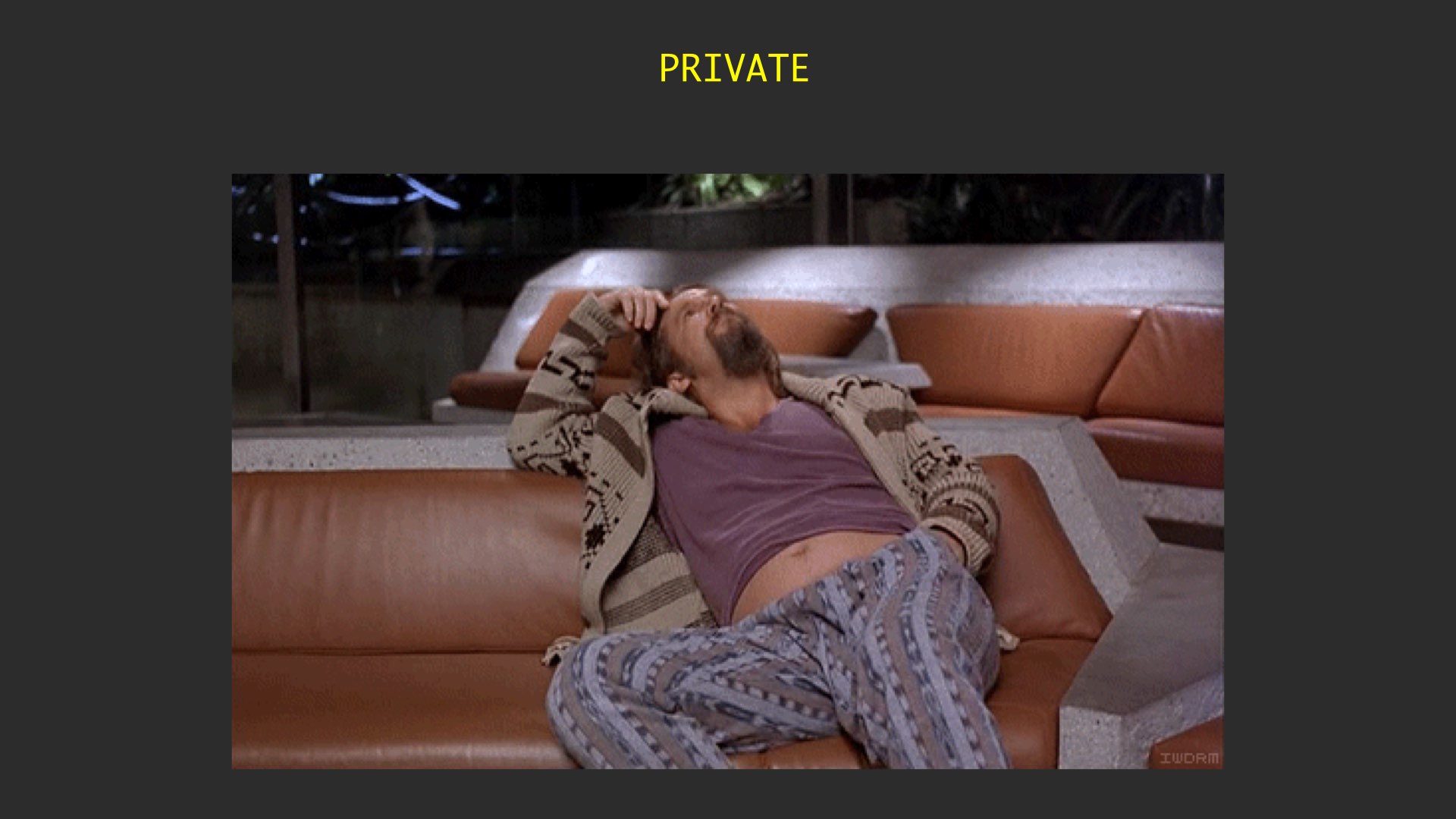

So: private attention. A good thing and a rare, typically accessible only to those with a highly evolved consciousness.

But reading is never private. It is always, at minimum, intimate:

And when shared with others can be convivial (a term I am borrowing from Ivan Illich’s great text Tools for Conviviality):

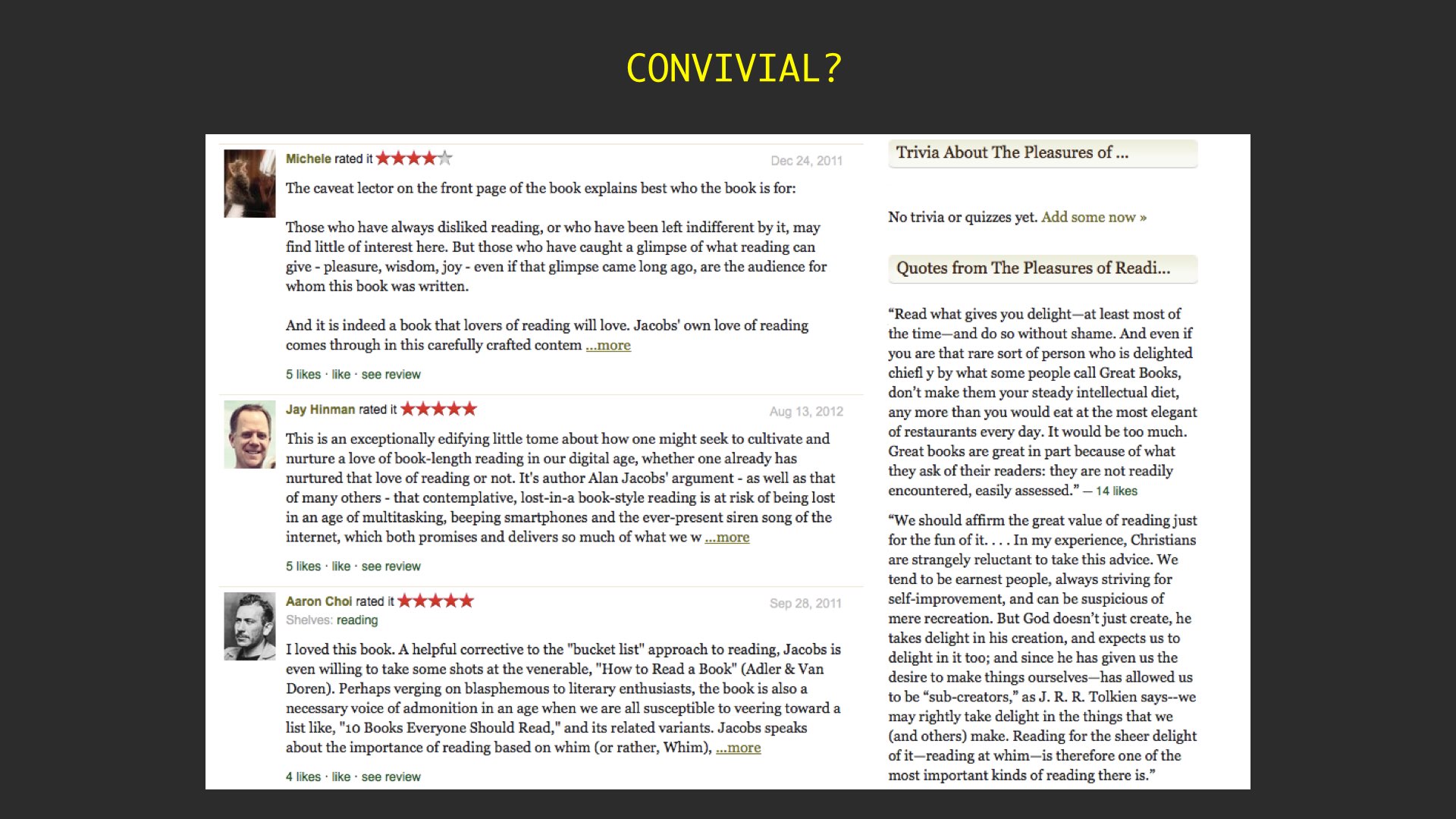

Is this a convivial environment?

We teachers certainly want it to be. But all too often it devolves into a kind of anonymous publicness.

Now, these distinctions are not easy to make. What, for instance, do we make of this kind of experience?

To hear Dickens read his work, in the company of hundreds of others, is clearly not the same as to read him in your “cone of silence” with a codex held up before your face — but is it necessarily a public experience. Or might the presence of other Dickens aficionados make it somehow convivial? Might it even be private, as though Dickens is speaking to you and only you, as the other members of the audience fade from your consciousness?

We can ask the same questions of the online world:

Can an encounter of fellow Goodreads users be a genuinely convivial experience, especially when you are agreeing about the merits of a particularly excellent book? Or must it be merely public?

But surely there can be no conviviality when there are no names, no identities, just numbers of highlights divorced from any particular highlighters.

Of course, one may desire a merely public environment, in which case: no problem. But often we may find that the modes of attention we prefer —

— are in tension with the environments of attention in which we find ourselves.

And as if this isn’t all complicated enough, there is a third factor to consider.

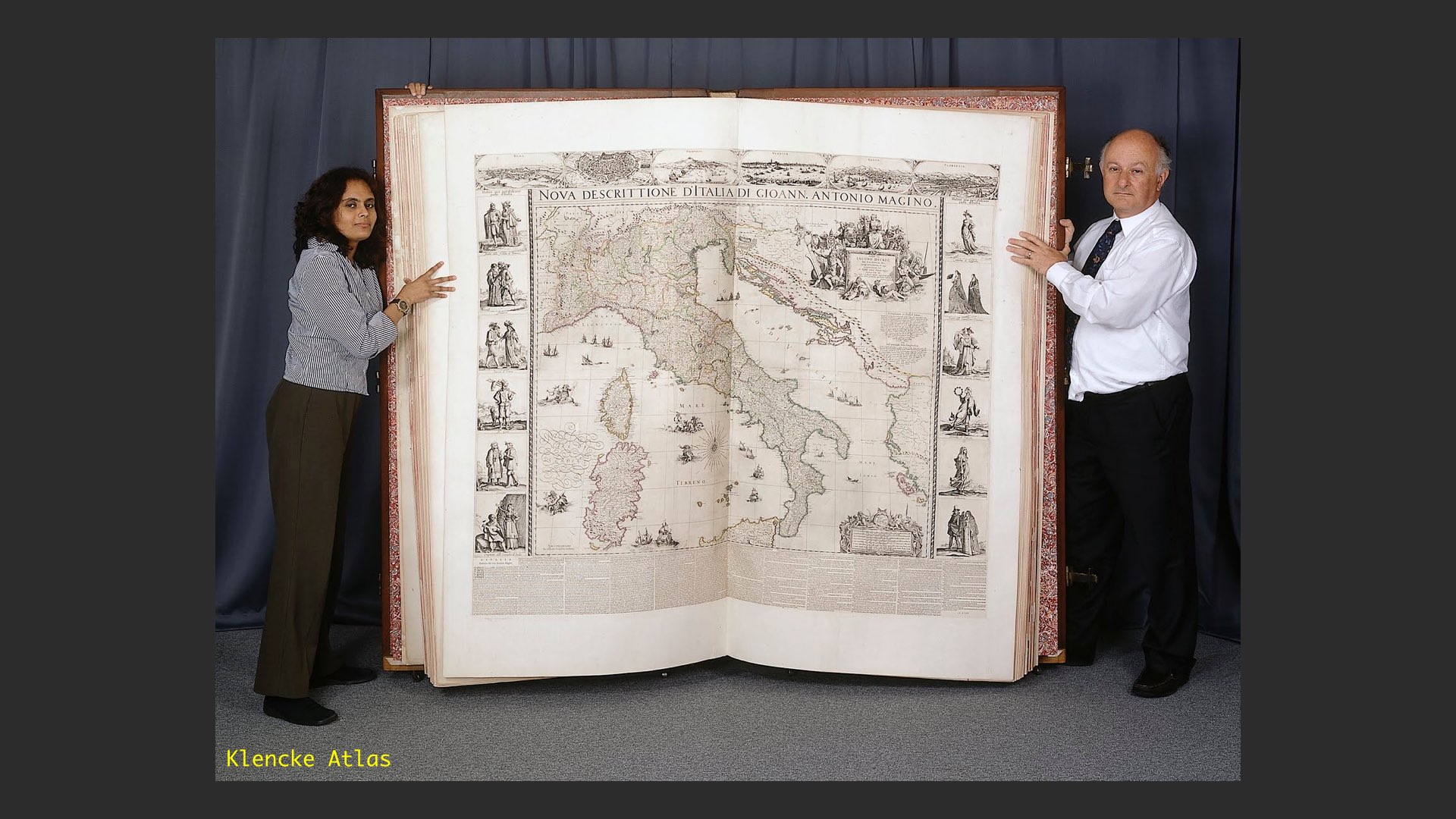

Here too, as the philosopher Bernard Williams used to say, “We suffer from a poverty of concepts.” We operate too often with a simplistic distinction between book (or codex) and screen. This is a codex:

But then so is this:

These are screens, and rather different kinds of screens, with different conformations and affordances:

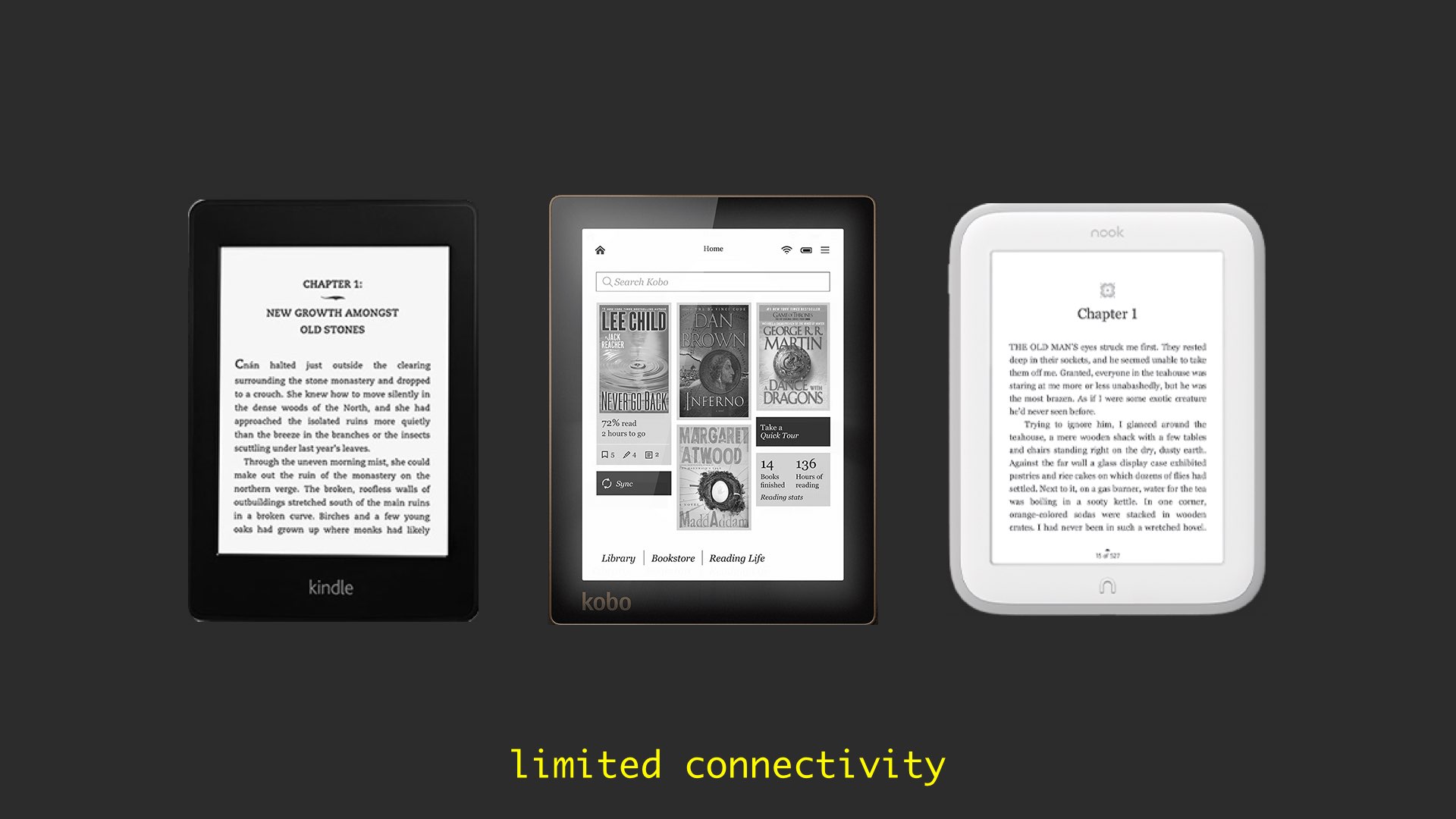

And so are these:

So it turns out that if we want to think seriously about how we read and the conditions under which we read, we require at the very least three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates:

As someone who was never very good with higher geometry, I am at this point tempted to retreat into a private realm:

But perhaps in that case I will not have earned my money. I shall therefore offer, by way of conclusion, …

For disputation.

(Precisely because it is task-specific, whereas the liberal-arts environment is devoted to the cultivation of more general intellectual habits, practices, and virtues.)

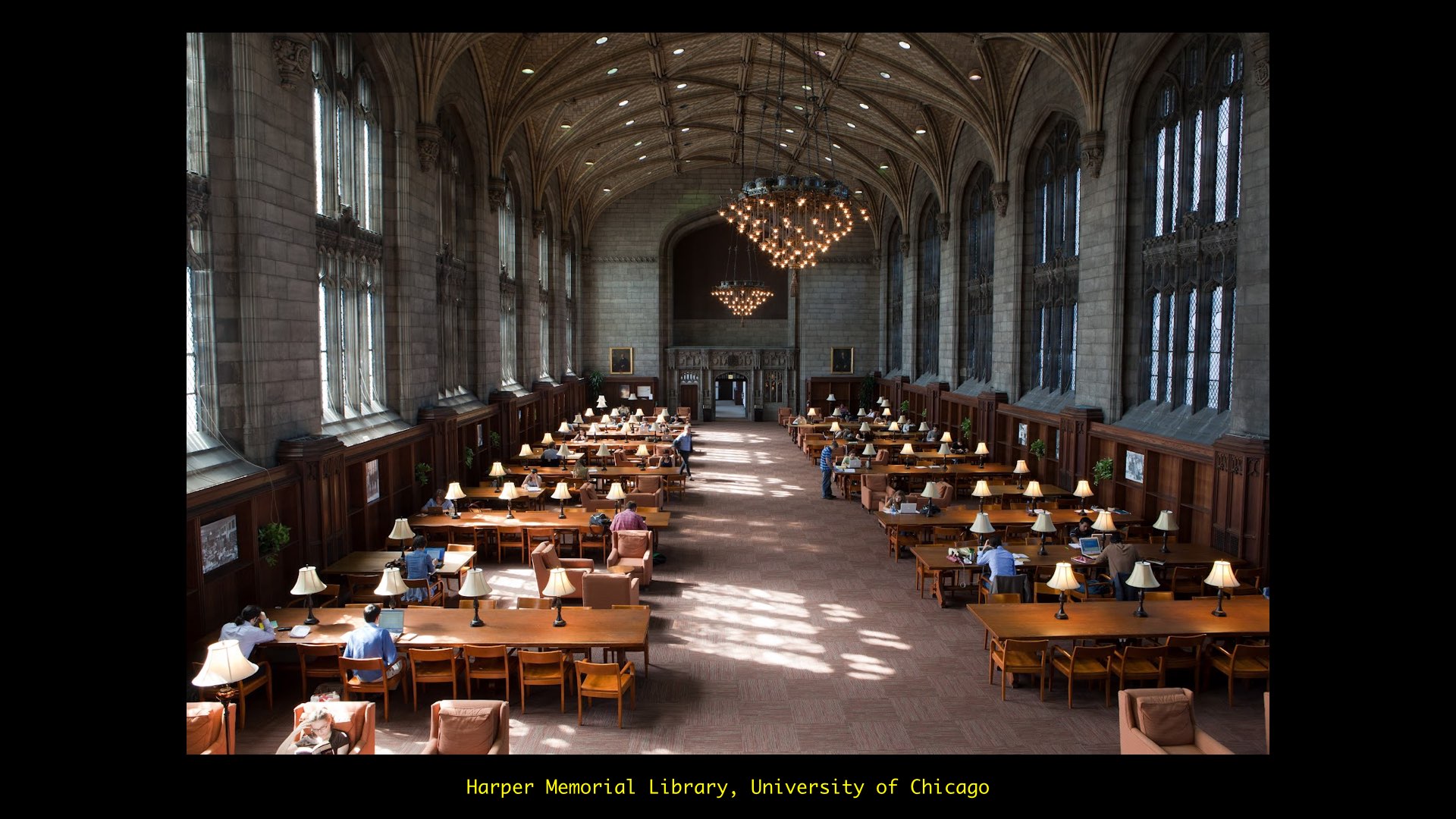

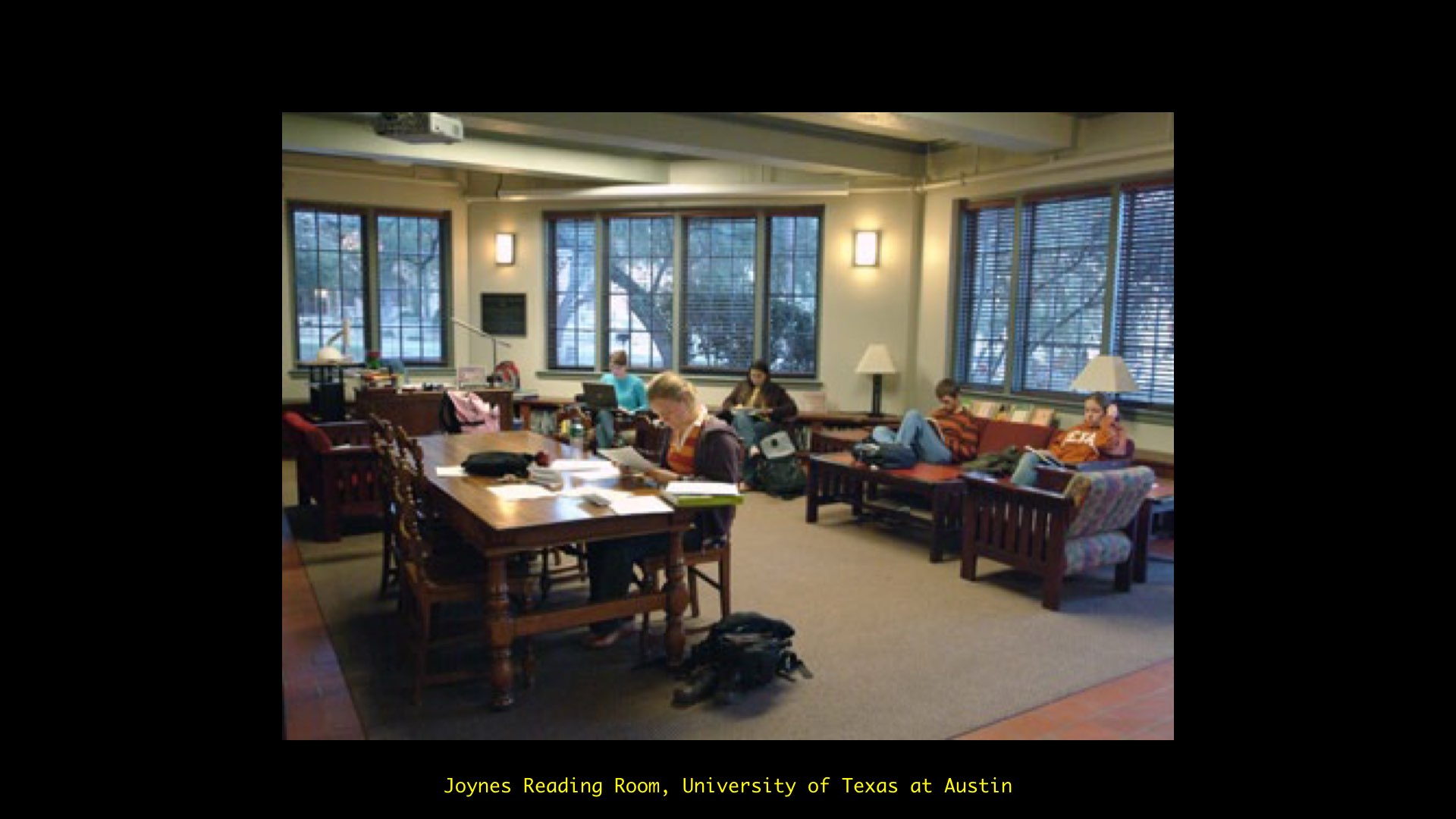

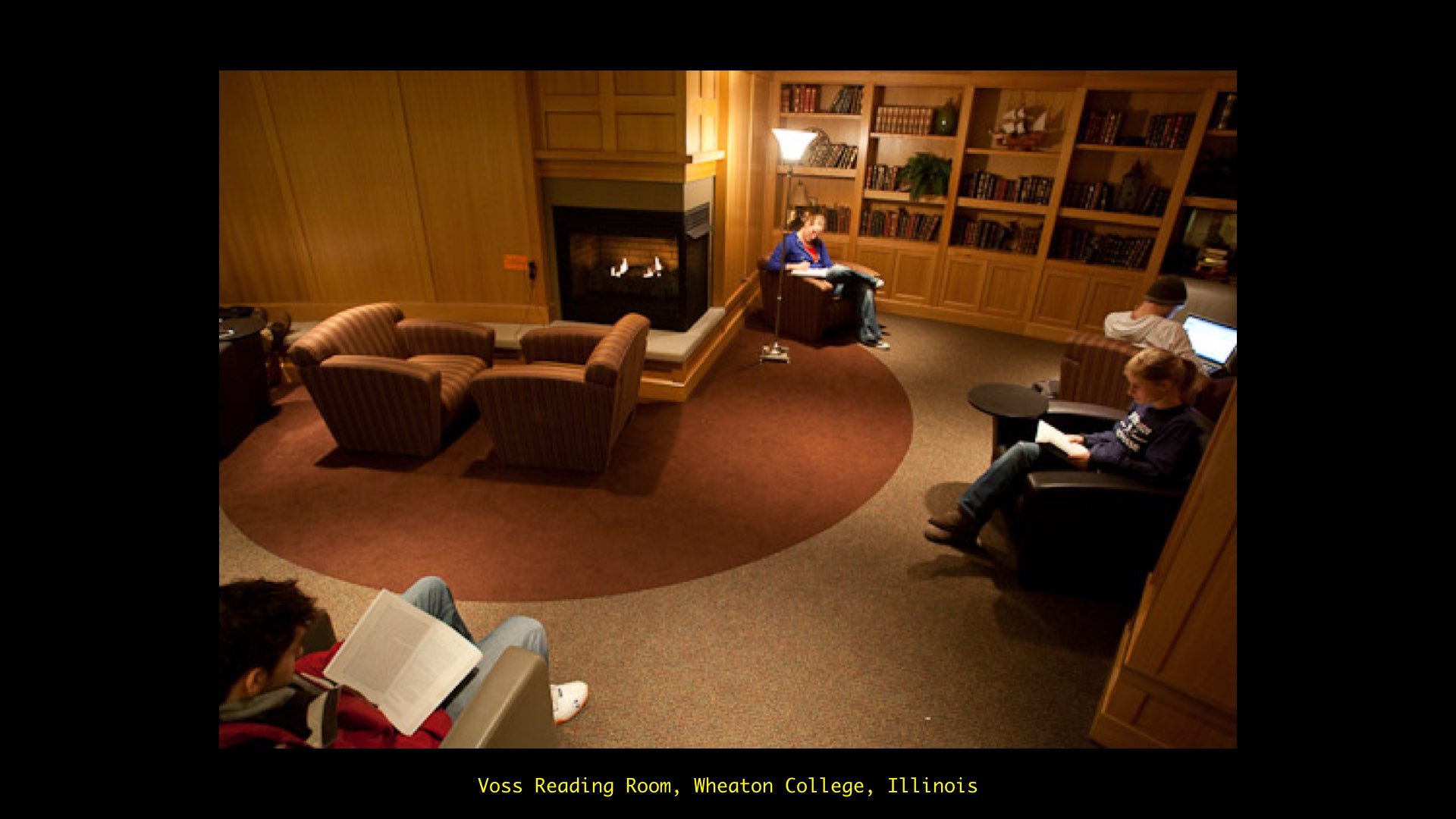

I want to talk for a few minutes about reading spaces at colleges and universities, some of which can be quite magnificent:

But magnificence is expensive — and may not be what we most need. There’s something to be said for other kinds of spaces, not grand enough to be public and too small to be especially convivial, that encourage intimate reading. (They should probably be Faraday cages, also.)

Along the same lines, we might think not just about books versus screens but about times to emphasize certain kinds of screens in preference to others:

Though we should never forget that not all connectivity derives from the internet: