Barth and Israel

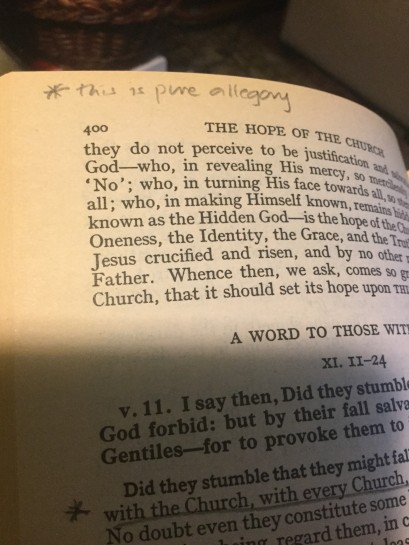

Above is one of several quite similar comments that I wrote in my copy of The Epistle to the Romans as I read Barth’s exegesis of Romans 9-11. So I was somewhat pleased and somewhat disconcerted to see how my friend Wesley Hill — unlike me, a professional in these matters — addresses Barth’s curious method here. In a thoughtful 2012 article, he acknowledges that Barth in exploring Romans 9-11 does not talk about Israel in any straightforward way, but Wesley then explores “metaphorical extensions” in Barth’s writing that “lead to the conclusion that Barth is doing more than simply reading a text about Israel as an allegory or parable for the life of the Christian church. They suggest, rather, that ‘Israel,’ ‘the Church,’ and ‘the world of religion’ are functioning within his commentary as ciphers for some reality inclusive of them all.”

This may be correct. But even if it is, and Barth is using a whole constellation of historical realities “as ciphers for some reality inclusive of them all,” that would just mean that he’s engaged in a even more abstract and comprehensive allegory than one that replaces “Israel” with “Church.” The key problem of Barth’s approach would in that case be simply intensified: his reading remains ahistorical and de-Judaizing — and it’s not clear to me whether he accepts the ahistorical in order to get the de-Judaizing, or vice versa.

I said in an earlier post that Barth’s commentary seems to be on the other side of some kind of divide, and I think that’s especially true of his reading of chapters 9-11. Remember that Barth insists that his project is to think with Paul, not mere comment on his letter. (That’s why Barth’s book has the same title as the text he’s commenting on.) So with that in mind, when Barth makes the historical Israel simply disappear from his commentary on 9-11, that can only be because he assumes that Paul isn’t really writing about Israel as such, but about some kind of universal “religious experience” of which Israel is merely an instance.

And I think this fits with Barth’s theology of krisis, a krisis which, he says over and over again, does not happen in history, at some particular moment in time, but is lifted out of the historical and into the eternal. “The eternal” always has a positive valence in this commentary, “history” a negative. And this is where Barth differs from us, who have learned to see the transcendent as expressing itself in and through the historical, and who have learned to doubt “religious experience” — and even “the world of religion” itself — as a useful category. In all these ways Barth is alien to us; and, I think, is simply and massively mistaken in his approach to Paul. Paul is clearly concerned, to the point of obsession, with the place of Israel in the Kingdom that has come in Jesus, given that (a) his fellow Jews have largely rejected the one Paul believes to be the Messiah of Israel as well as the world’s Savior and (b) “the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable.” You simply cannot think with Paul unless you pursue this question, a question so intractable that Paul ends his meditation by confessing that it is wholly beyond his powers of understanding: “Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!”

But in other respects Barth still provides an important model. I said in one of those earlier posts that Barth seems to be taking the dialectical character of Romans 7 as the model for his own theological rhetoric, and perhaps ignoring the other rhetorical modes of Paul’s letter, but in 9-11 we see Paul being just as thoroughly, passionately dialectical as in 7. Perhaps that back-and-forth, this-and-yet-also-that movement of Paul’s mind really is normative for him, or at least for this letter, and really should be imitated by the commenter who wants to “think with Paul.” I was too quick to say that Barth is over-relying on chapter 7.

More reflections to come later. And please remember that these are the unprofessional reactions of a mere reader.