what to say about First Things?

People keep writing to me about the Reno Incident, usually wanting to know what I think it says about First Things as a magazine, and aside from saying, on Twitter, that I think this post by Rod Dreher puts the whole business in the proper context, I’m not sure what to add. But I’m gonna give it a try.

My history with First Things is long and rather complicated. I’ve written about it before, in bits and pieces, but let me sum up here. When the magazine was just a few months old, I found a copy when, on a visit to the University of Chicago, I ducked into 57th Street Books to browse the periodical shelves. There was nothing like it at the time, at least that I knew of, and I fell in love right away. A magazine that took both religion and ideas seriously! First I subscribed, and then I submitted two shortish essays to the editors. Jim Neuchterlein wrote back accepting one of them — strangely enough, it was about Talking Heads — and a beautiful friendship was born. Over the next two decades I appeared in the magazine approximately fifty times: feature essays, shorter opinion pieces, book reviews.

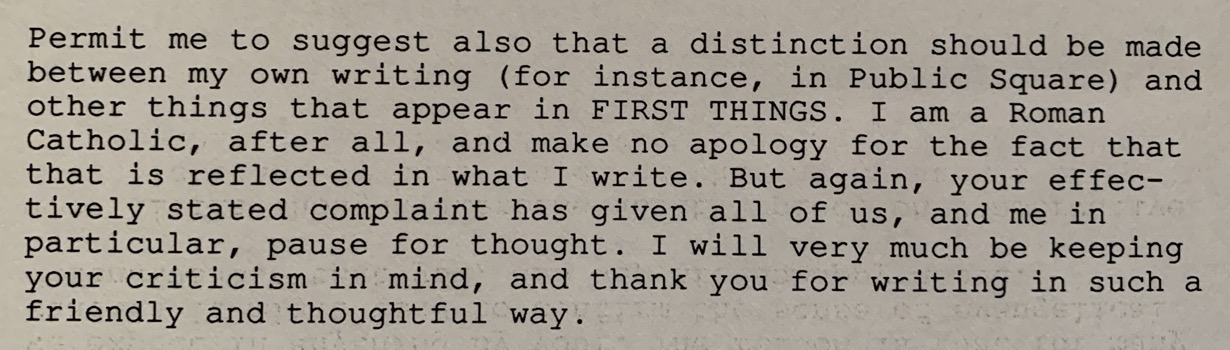

I did sometimes feel, after Richard John Neuhaus became a Roman Catholic and then a priest — having before that been a Lutheran minister —, that the evangelical wing of small-o orthodox Christendom was occasionally slighted in the pages of the journal, and once I wrote to Father Neuhaus to tell him so. After a few days he replied:

Well, I thought, that’s generous. And then a bit of gentle pushback, followed by further reassurances:

And, as if he hadn’t completely won me over, this concluding flourish:

He could charm, that man.

I loved writing for First Things, and if I had had my way, I’d have spent the rest of my career writing for that magazine and for John Wilson at the late and so-deeply-lamented Books & Culture. (John’s greatest gift to me, as an editor, was to connect me with books that I could interact with creatively; Jim Neuchterlein’s greatest gift was to teach me about the control of tone, something I really struggled with early in my career.) But I did not get my way. B&C was shut down, and even before that things started getting weird at FT. I have always liked Jody Bottum, and admire him as a writer, but as an editor he was difficult to work with, and when Jim retired and Jody took over, he simply rejected everything I sent him. I had had no rejections from FT in twenty years, and now I could get no acceptances! It was never clear to me exactly what was going on — especially since Jody kept telling me what a wonderful writer I was — but eventually I gave up and started looking elsewhere. Which is how I ended up writing for places like the Atlantic and Harper’s and the New Yorker — because I wasn’t good enough for First Things. Or was no longer “a fit,” anyway. It was, and still is, hard for me to know how much I had changed and how much they had.

Not, for a long time, being willing to give up altogether, I managed to get a handful of things in the magazine, but it was obvious that my relationship with it was never going to be the same. And then things started getting more generally strange. A kind of ... I’m not quite sure what the word is, but I think I want to say a pugilistic culture began to dominate the magazine. When I submitted a piece to an editor, another editor wrote me an angry email demanding to know why I hadn’t submitted it to him; whenever I disagreed with Rusty Reno about something, he would, with such regularity that I felt it had to be intentional, accuse me of having said things I never said; once, when I made a comment on Twitter about the importance of Christians who share Nicene orthodoxy working together, another editor quickly informed me that I’m not a Nicene Christian. (Presumably because, since I’m not a Roman Catholic, I don’t really believe in “the holy Catholic church.”)

I suspect all these folks would tell a different story than the one I’m telling, so take all this as one person’s point of view, but more and more when I looked at First Things I found myself thinking: What the hell is going on here? Sometimes the whole magazine seemed to be about picking fights, and often enough what struck me as wholly unnecessary and counterproductive fights. (Exhibit A: the Mortara kerfuffle.) So I stopped submitting, and then I stopped subscribing, and then for the most part I stopped reading. This isn’t a matter of principle for me: Whenever someone recommends a piece from the FT magazine or website to me, I read it, and if I like it I say so (usually on Twitter). But effectively there is no overlap any more between my mental world and that of First Things. I regret that.

Rod Dreher is correct to say, in a follow-up to the post I linked to at the top of this piece, that no other magazine of religion and public life, or religion and intellectual life, has the reach of First Things. But I think the decision by the editors of FT to occupy the rather ... distinctive position in the intellectual landscape that they’ve dug into for the past few years has left room for a thousand flowers to bloom in the places that FT is no longer interested in cultivating. I have gotten more and more involved with Comment; they’re publishing some outstanding work at Plough Quarterly; even an endeavor like The Point, not specifically religious at all, makes room for religious voices: My recent post there on Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life would surely have been an FT essay in an earlier dispensation of the magazine. All is not lost. But I fear that First Things — at least in relation to the mission it pursued so enthusiastically for a quarter-century — is lost.