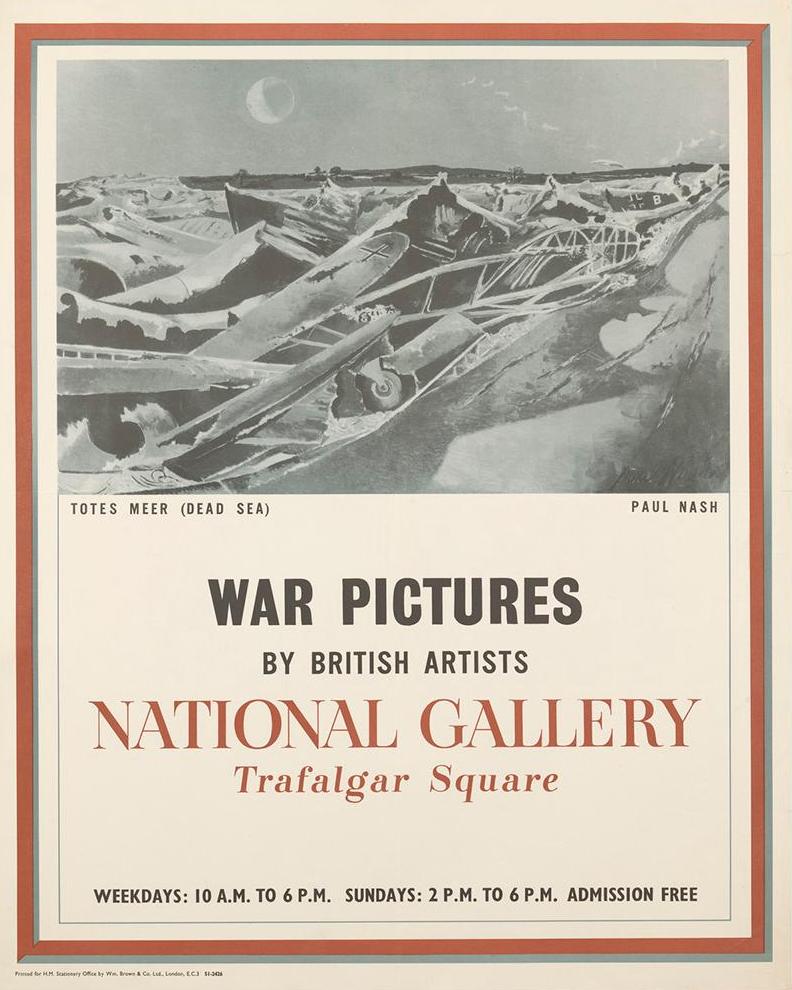

a kind of parable

In yesterday’s post I mentioned the upsurge in the British public’s interest in art during the Second World War. Exhibitions like the one advertised above were all over London — you see several of them in Out of Chaos — and the National Gallery could show the work of living artists because it had empty walls: all of the works of the dead ones had been packed up —

— and moved to an unused mine, called the Manod Caves, in north Wales:

For certain staff members this was not the worst thing that could have happened. The two chief restorers, W.A. Holder and Helmut Ruhemann, now had the opportunity to attend to damaged or merely age-worn paintings in solitude and with all the time they needed. Here’s Holder with Sir Kenneth Clark — later to become world-famous thanks to Civilisation, but then the director of the National Gallery:

The windows in the background suggest that this photo was not taken in the Manod Caves but rather in one of above-ground locations in Wales where the pictures had originally been moved before Clark decided that they weren’t safe enough. (Many more excellent photos of the Great Removal may be found here.)

Ruhemann didn’t stay in Wales long — he took other jobs during the war, though eventually he returned to the National Gallery — but Holder worked in the caves for the duration. I like to think of him there, laboring patiently, quietly, persistently to repair and restore beautiful objects — works born of insight, imagination, and craft but damaged by neglect and the relentless passage of time. Outside the world is convulsed, and God bless those who fight for all they’re worth against its evils, but some of us are called to protect and preserve and restore our inheritance, waiting and hoping for better days, days when we emerge bearing what we have repaired to announce our heartfelt invitation.