difference

Lately I’ve been re-reading the stories that Alice B. Sheldon wrote under the name James Tiptree, Jr. and it occurs to me that almost all of them are meditations on the same theme: The way genuine difference, especially but not only sexual difference, simultaneously alienates and allures. Now, I should also add that the Tiptree stories seem unable to imagine this dialectic settling into a healthy tension; almost invariably the alienation and the allurement alike take pathological forms.

In “And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill's Side” we meet a man and, eventually, his wife who are in the grip of a kind of sexual xenomania, obsessively lusting for aliens of various species in a way that the man perceives as pathological but inevitable. Sometimes the man sees in the aliens a kind of beauty, and traits that present in exaggerated form what he finds desirable in human women, but essentially it is the very alienness that obsesses him: His sexual passion is awakened by the impossibility of sexual union. (This is also the theme of Samuel R. Delany’s famous story “Aye, and Gomorrah.”) The story’s title, of course, comes from Keats’s poem “La Belle Dame sans Merci,” in which a knight’s life is destroyed by his encounter with a beautiful fairy, an encounter with otherness that infects him with a permanent obsession that becomes a wasting disease.

But Tiptree’s stories often suggest that pathology dictates the typical patterns of relation between human men and human women. In “The Women Men Don't See” the women of the title are not sexually desirable to the man who narrates the story and are therefore invisible to him; he only sees them at all when he’s trying to decide whether they are potential sex partners, or rather sex objects. One of the women, the mother of the other one, understands this, and says to him,

“Think of us as opossums, Don. Did you know there are opossums living all over? Even in New York City.”

I smile back with my neck prickling. I thought I was the paranoid one.

“Men and women aren't different species, Ruth. Women do everything men do.”

“Do they?”

When, later in the story, Don discovers that the woman has planned an encounter with aliens and wants to be abducted by them, taken away from Earth, his first response is to try to shoot the aliens — but (of course; the story is very on-the-nose in multiple respects) he ends up shooting Ruth instead. She is not badly wounded, and later they have a final conversation.

“I think they're gentle,” she mutters.

“For Christ's sake, Ruth, they're aliens!”

“I'm used to it,” she says absently.

Living with men, living with other terrestrial species, living with aliens — it’s all the same to Ruth. (It’s no accident that she shares a name with the biblical character who leaves her homeland to dwell among strangers.) To the aliens, who insist in halting and malformed English that they are students, that they want to learn rather than harm, she will be an object of intense attention — they will see her. But is that kind of being-seen any better, really, than being invisible? She stakes her life on the possibility, however remote, that it will be; because she has no hope at all for the world she was born into.

“Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” — another haunting but schematic story — imagines a future in which, by some kind of time-accident, three astronauts are thrown forward into a future world in which all living humans are female clones. They are rescued from their ship and brought into one occupied by five women. Under the influence of a disinhibiting drug, the astronauts reveal their true impulses: one of them is consumed by a mania for domination, a second is consumed by violent sexual lusts, and the third, the classic “beta male,” feels both of those impulses but in a muted way. (I told you the story is schematic.) It seems obvious to the women — who observe these men with a kind of detached curiosity, as, perhaps, the aliens in “The Women Men Don’t See” will observe Ruth and her daughter — that the re-introduction of males into human society, a re-establishment of the old ways of sexual reproduction, would be a Very Bad Idea Indeed. Difference is interesting to them, perhaps, but after several hundred years of life without men it’s not interesting enough to make them want to change their social order. Much alienation, little allurement.

In the darkest Tiptree stories, the allurements of difference are depicted as fundamentally irrational impulses — irrational, but so powerful that they don’t allow for the calm decisions to separate and isolate that mark the decisive moments in “The Women Men Don't See” and “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” The fantastically weird “Love Is the Plan the Plan Is Death” describes a species of creature, right on the cusp of sentience, one member of which tries to find ways to override the impulse to eat what you love. It turns out, though, that he, being male, isn’t one of the eaters; and that sometimes creatures do what they’d rather not do — if that’s The Plan. And in what seems to me Tiptree’s darkest story, “A Momentary Taste of Being,” the human passion to reach the stars is nothing other than the impulse that drives spermatozoa into a hostile environment where almost all of them will die.

Difference can be profoundly alluring, these stories seem collectively to say, but we should heed the countervailing feeling of alienation — if we can. It would be rational … but, in the end, how powerful is reason?

It’s fascinating to read these stories in our present moment, in which race occupies essentially the same cultural territory that sex occupied for Alice Sheldon and other women of her time. I suspect that Sheldon would have thought and maybe even felt differently about the alienation/allurement dialectic if she had had available to her our culture’s passionate commitment to gender as a social construct that is (therefore, so the faulty logic goes) amenable to infinite performative manipulation by individuals. For us, it’s racial difference that is especially often experienced in the way that Sheldon experienced sexual difference. When Reni Eddo-Lodge wrote Why I'm No Longer Talking to White People About Race she was basically making the decision that the women in “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” make about men.

The homologies between racism and sexism are not new, of course, and we can trace them back a long way: for instance, it’s worthwhile, I think, to map the concerns of “The Women Men Don’t See” onto the similarly knotted tension between not-being-seen and being-seen-badly in Ellison’s Invisible Man. But because race is such a massive component of our current political disputes, people now commonly choose and indeed embrace alienation in that whole sphere. (I’ve have recently learned that a large family of my acquaintance, well known for its cheerful closeness, has now been divided and broken by disagreements over Donald Trump. And at least some members of the family feel that it would be morally irresponsible not to be so broken.)

I think it’s because race is so widely seen to be intractably binary — Whites and Others — while gender and even sex are seen as chosen and performative that racial tension has taken hold of our public imagination in ways that the #MeToo movement, in the end, didn’t. Think for instance of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo: his behavior towards women has been despicable, but he easily survived the outrage, which proved to last only a few days. (Alice Sheldon would not have been surprised by the behavior or the tolerance of it.) If his sins had been equal in seriousness but racist in character — if he had demonstrably treated Black people around him with the same callous manipulative disregard that he treated the women who worked for him — would he have a job now? The question answers itself.

(Of course, if he had been a Republican governor, then he would have had the smoothest sailing imaginable. Openly, bluntly racist figures are perfectly welcome in today’s GOP; it’s only critics of Donald Trump who aren’t. But that’s a story for another day.)

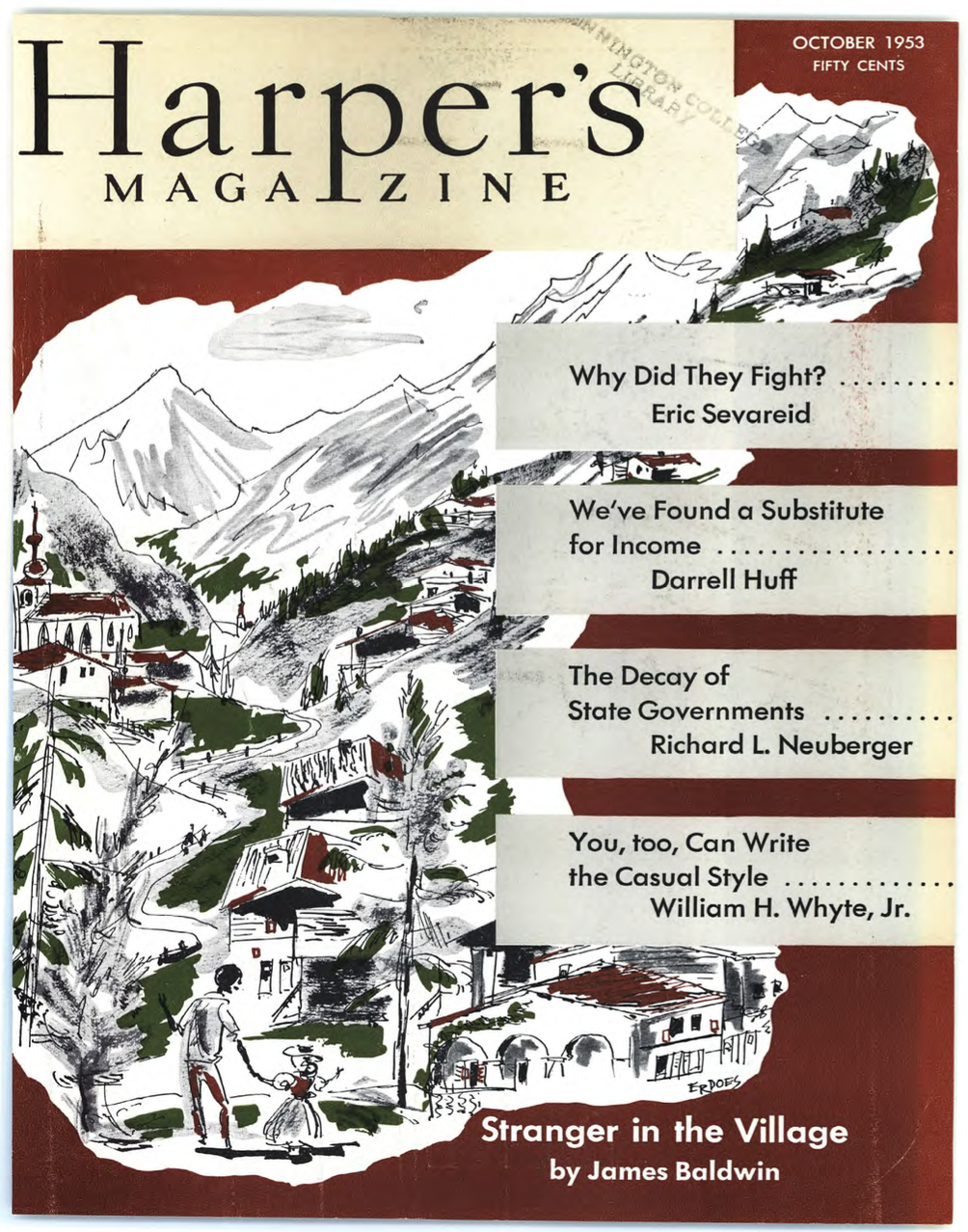

By way of conclusion, I’m going to make a simplistic statement that I may perhaps be able to unpack later: I believe that what we need when thinking about all forms of difference is (a) a frank acknowledgement of both allurement and alienation, and (b) an ability to achieve a genuinely tragic sense of history that does not succumb to despair. We should begin, collectively, by reading James Baldwin’s essay “Stranger in the Village.”