indices

Lots of enjoyable coverage of Dennis Duncan’s new and wonderfully titled Index, A History of the. (You may find a brief excerpt from it as a work-in-progress here.)

The best thing I’ve seen is (unsurprisingly) by Anthony Grafton in the LRB. Here’s a noteworthy passage:

Indexing flowered at a time when readers saw books as great mosaics of useful tags and examples that they could collect and organise for themselves. The chief tool they used to do this job was not the index but the commonplace book: a notebook, preferably organised by subject headings known as loci communes (common places), which provided both a material space in which to store material and a set of designators to help retrieve it. Like indexes, commonplace books were wildly popular. John Foxe, a corrector of the press during his exile years in Switzerland, printed two editions of a blank commonplace book designed to be filled in by users under Foxe’s various headings. One such user, Sir Julius Caesar, crammed his copy so full of notes and excerpts that the British Library classifies it as a manuscript. In his preface to the first edition, Foxe made clear that he knew he was riding a wave. He worked for Johannes Oporinus, the Basel printer who brought out the Magdeburg Centuries, a vast Protestant history built on commonplace books compiled by students. Foxe pointed out, with relish, that everyone who was anyone was making commonplace books and telling others how to do so. Humanists commonplaced to ready themselves for effective speech and writing, medical men, lawyers and theologians to prepare for their professions. Foxe argued that the commonplace book was vastly superior to the index. The index might point you to the materials you need, but the commonplace book actually provided them, handily organised. Holmes, like his contemporary Aby Warburg (another dab hand with scissors and paste), was a late master of the commonplace book, even if he called it an index. If printing made indexes easy to compile, commonplacing made them indispensable to printers and readers alike.

In response to the TLS’s review, my dear friend Tim Larsen wrote in with the following:

I can confirm that one does indeed need a human indexer with a decent knowledge of the topic at hand. I thought I could safely ignore the index for my Oxford Handbook of Christmas (2020), but when it came back with an entry on “Joseph, father of Jesus,” I knew I had to step in. Mercifully, it went to press as “Joseph, husband of Mary.” As to humour in indexes, one of my favourites is E. P. Sanders’s Paul and Palestinian Judaism (1977). Its index has an entry for “Truth, ultimate.” The three pages listed under it lead one to the blank pages that divide the book’s parts.

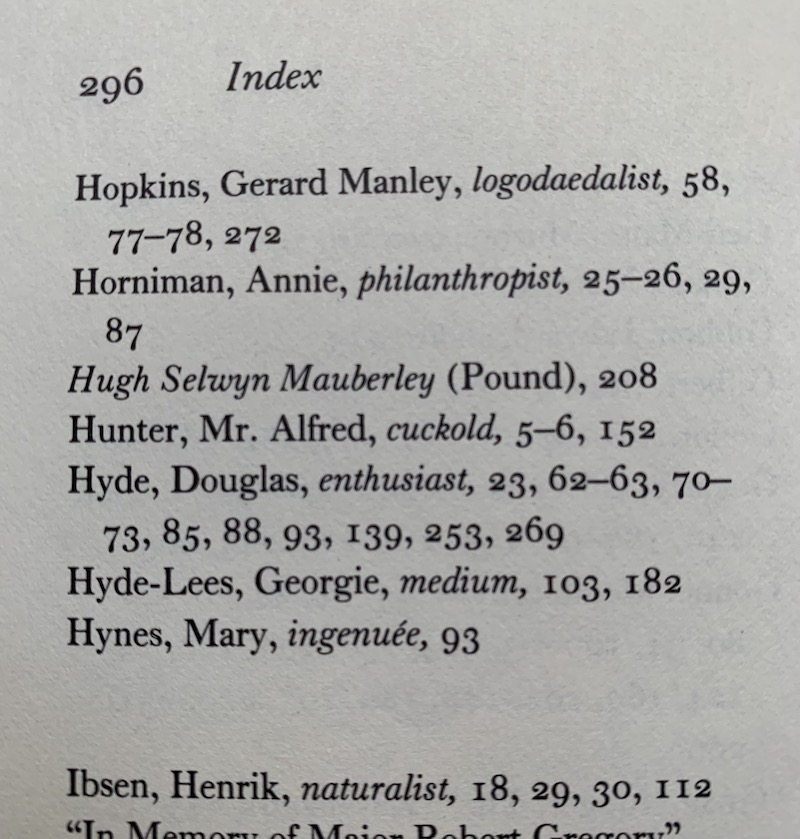

Let me register a vote for My Favorite Indexer: Hugh Kenner. In some of his books he not only tabulated references to key figures, he offered memorable single-word descriptions of many of them. A few examples from his book on Irish writers, A Colder Eye:

Of course, the delight here is turning to the appropriate pages to find out just how Kenner settled on the identifications he chose.