a revaluation

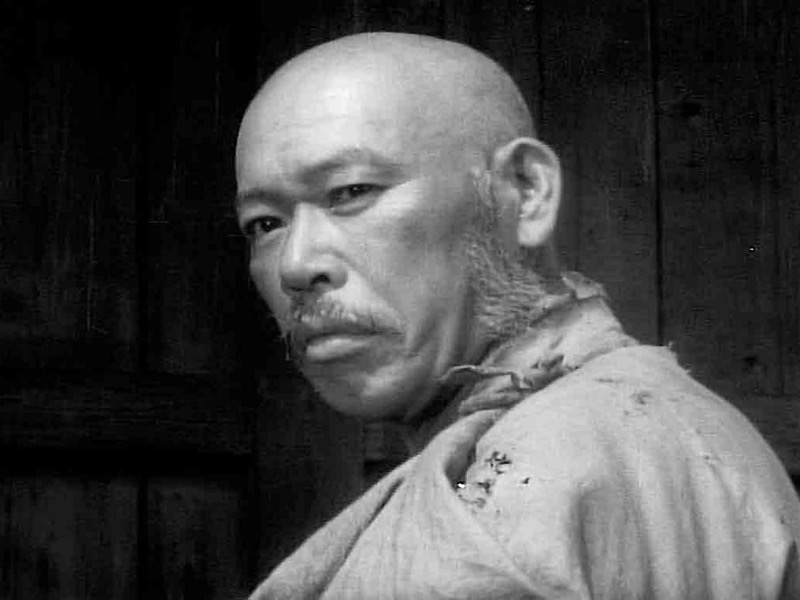

Here is the great Takashi Shimura as Kambei Shimada, the leader of The Seven Samurai (1954):

A man to be reckoned with. A calm but unyielding and fearless leader of warriors. And here’s Shimura two years earlier, as the dying bureaucrat Mr. Watanabe in Ikiru — a timid man, a man so lifeless and dull that one of his co-workers nicknames him “the Mummy”:

He was also the kindly peasant woodcutter in Rashomon and the professor in the original Godzilla! Which is a pretty remarkable string of major roles, comparable perhaps to Harrison Ford’s run in the early 80s as Indiana Jones, Han Solo, and Rick Deckard. But Shimura’s sheer range is unmatched, I think. Even now, forty years after his death, we ought to be talking about what an astonishingly versatile actor Shimura was, compelling in every role.

But that’s just by-the-way. What I really want to talk about here is the filmmaker most closely associated with Shimura, the director of Rashomon and The Seven Samurai and Ikiru, Akira Kurosawa. (No, Kurosawa didn’t direct Godzilla, but if he had….) The argument I want to make here is that Kurosawa has experienced a fate that no one would have predicted of him fifty years ago: as a director, he is significantly underrated.

For many years, starting with the overwhelmingly delighted response to Rashomon at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, Kurosawa was the Japanese film director — he eclipsed all others, at least in the eyes of Western audiences. (Indeed, you could make the case that The Seven Samurai is the most influential film ever made — even if you think only of how many movies have stolen its most obvious plot device, the let’s-assemble-the-gang first act. But the way Kurosawa films his action scenes, copied by filmmakers ever since, has been equally influential.) But this celebration of Kurosawa did nothing to elevate the status of other Japanese filmmakers, including the two who have a strong claim to be his superiors: Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi. They only gradually made their way into the public consciousness.

One of the best film critics alive — one of the best ever —, David Thomson, has written that he has often been rather hard on Kurosawa precisely because he is annoyed that Kurosawa’s reputation has displaced Ozu and Mizoguchi, whom he thinks obviously the greater artists. But that was a mistake, for two reasons: first, because you cannot elevate the reputation of some by attacking the reputation of others — it just doesn’t work that way; and second, because it is not at all obvious (to me, anyway) that Kurosawa is a lesser filmmaker than Ozu and Mizoguchi.

I don’t say this carelessly. If I had to pick a Greatest Director, it would probably be either Ozu or Jean Renoir. But lately I have been thinking about this: Kurosawa is best known for his historical films, especially the ones focused on samurai culture, and yet Ikiru — a film set in 1950s Japan, in an urban setting, focusing on family and the workplace — in short, a film very like Ozu’s most famous ones, a perfect example of the shomin-geki — may well be Kurosawa’s masterpiece. And it is in every way worthy to be compared with Ozu’s transcendentally great Tokyo Story and Late Spring.

That still could easily have been from Ikiru, though in fact it’s from Late Spring. The two films occupy much the same world.

To be sure, anyone who knows Ozu’s cinematic grammar would never for a moment think that Ikiru was one of his films. The camera is too mobile; the height of the shots too variable; the transitions too different. (Kurosawa frequently employs horizontal wipes to change scenes, something Ozu probably never did in any of his forty or more films.) Still, Ikiru and Ozu’s masterpieces of the same era are spiritually kin — closely kin; they tug at my heartstrings in very similar ways, with very similar effects. And if Kurosawa could make an Ozu-like film, Ozu could never in a million years have made The Seven Samurai.

So I’m on something of a Kurosawa kick right now, and re-evaluating his body of work. He’s much less subtle than Ozu and Mizoguchi … but subtlety isn’t everything. Sometimes the direct approach is the best. And rarely did any director make the direct approach more skillfully and compellingly than Kurosawa does.