Little, Big

My friend Adam Roberts wrote recently about John Crowley’s Little, Big, which is (a) one of my very favorite novels and (b) a book I have never written about. I suspect that I've never written about it precisely because it means so much to me. One day perhaps I will get to the bottom of this. But for now I just want to make a few comments.

One: Adam thinks the book is a version of baroque, but I don’t think I agree. My inclination is to say that there are forms of elaboration other than the baroque, and Crowley dwells in one of those traditions. His imagination, especially his visual imagination, seems to me to arise from the vision of art that begins with the Pre-Raphaelites, moves on through William Morris, and culminates in the Arts & Crafts movement, which in the first two decades of the twentieth century — the period in which Edgewood was built — was a very big thing in the upstate-New-York world to which Crowley is always drawn. (The Aegypt books are set there too.) Edgewood is surely a house in this tradition, though in its decorated rather than its spare aspect. If you imagine Richard Norman Shaw’s Cragside sitting in a heavily forested corner of the Catskills I think you might envision Edgewood correctly.

Also, the women of Little, Big are often very much in the Pre-Raphaelite “stunner” mode. (Primarily the Elizabeth Siddall cascading-redhead type rather than the Jane Morris darkly-brooding type.) Cf. Rossetti’s The Beloved, which could be a depiction of the enthronement of Daily Alice:

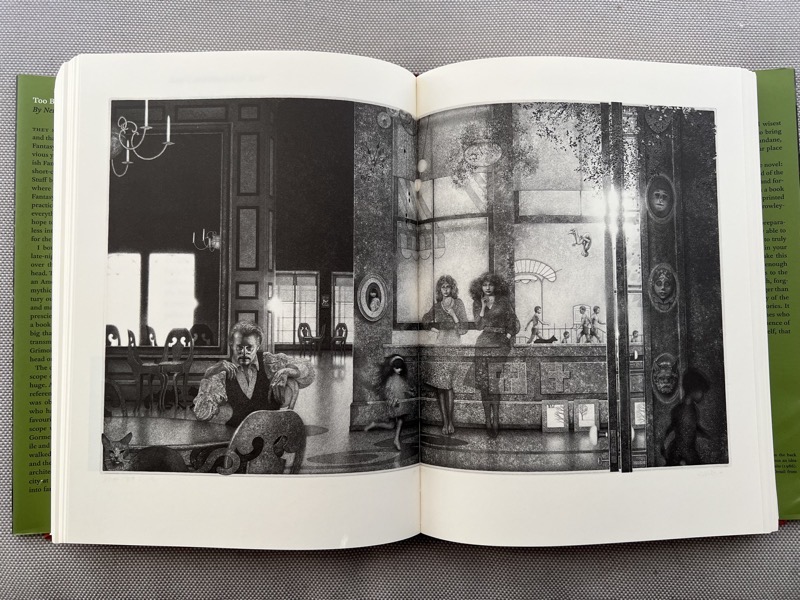

Peter Milton’s illustrations for the rather magnificent 40th anniversary edition of the book capture some of the feel of the novel, though with an Art Deco tinge that might not be elaborate enough:

That’s not wrong, exactly, but I think it’s missing the density of detail present in so many Pre-Raphaelite paintings and William Morris designs, e.g. the Green Dining Room:

I think if you stripped the Pre-Raphaelite visual world of its medievalism — there ain’t no medieval culture here in the Americas — you’d be getting close to the visual aesthetic of Little, Big.

Two: I think almost the whole of Crowley’s imagination — in his fantasies, though not in his many non-fantastic writings — derives from two books, both of them by Frances Yates: The Art of Memory and The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. The first is a book about making the events and experiences and encounters of the past meaningful and coherent; the second is a book about achieving a nirvana, a wholly enlightened consciousness. The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz is re-enacted or re-interpreted several times in Crowley’s work, including the marriage of Smoky and Daily Alice. (Colin Burrow, in an essay that Adam cites, notes this influence and thinks that current scholarly skepticism about Yates’s arguments creates a “big problem” for Crowley’s fiction, though I don’t know why that would be. Surely works of literary art don’t need to be grounded in sound scholarship to be good stories. The discrediting of the Ptomelaic cosmos doesn’t make the Divine Comedy less compelling.)

It may be that Crowley sees us as having to choose between the two visions of Yates’s two books: that is, we can have a history that takes beautiful form or a beatific vision of total Meaning. Those granted nirvana leave their history behind, as the fairies leave behind Edgewood; that it is “a house made of time” is why they must leave it. You could say that Edgewood is the real protagonist of the story because it enables enlightenment for the fairies and for Smoky the completion of his Tale. And so at the end it runs on, telling its story because it doesn’t know how to do anything else, though both of its audiences have departed. I don’t know anything lovelier in literature than the final paragraph of Little, Big, a book that does not begin but rather ends with “once upon a time.”

(There are, I think, three chief sources of image and myth in Crowley’s fantasies: the Arts & Crafts movement, the Rosicrucian Enlightenment, and one more: the counterculture of the Sixties, which I think Crowley sees as, at its best, inheriting those earlier movements — but never quite laying firm hold on them. Swerving from what it could have been and should have been. But that’s more of a theme in the Aegypt books than Little, Big.)

Three: Little, Big is full of Sehnsucht, it is a “search for the blue flower” story, and I don’t know any other book that better depicts this experience. (I don’t agree with Burrow that such a fantasy is “a conscious substitute for the magic in which you don’t quite believe any more”; I think it’s in no way a substitute, but a pointer towards something that necessarily remains always out of reach.) I also think — and this is not unrelated — that Little, Big is an illustration of the fact that for us mortals “death is the mother of beauty”: Smoky’s apprehension of the Tale is shaped wholly by the fact that he will not inherit it, is not made to inherit and inhabit it, but through helping it to come to be he plays a part that only an outsider to its full enactment can play. It is beautiful to him in a way that it cannot be to its participants; that is its gift to him. There is an inevitable asymmetry in his marriage which somehow make it stronger and more wonderful rather than weaker: he loves Daily Alice differently than she loves him. She occupies almost the whole of his short life; he can be to her only a moment, though perhaps the dearest moment, in an endless one. (It is very sweet to me that she and only she knows where he is buried.)

I think by calling attention to this asymmetry he remedies the biggest defect in The King of Elfland’s Daughter: Dunsany never acknowledges that by bringing the whole of Erl into Elfland he has taken away the very thing that makes Lirazel ache for her husband and family: their mortality. Blake’s “Eternity is in love with the productions of time” is the mirror-image of Sehnsucht, and Crowley gets that, while Dunsany, I think, does not.