fabulism

I was a fabulist as a child, and indeed, well into my adolescence. It was perhaps the signal trait of my character. I have a fairly elaborate justification for my habitual lying: it begins with the fact that I was two years younger than my classmates through most of my school years. I had started first grade at age five and then skipped second grade, something that would not be done now because of a greater awareness of the psychological and psychosocial damage such a practice inflicts on a child. But in my now-distant youth, I guess people didn’t know any better. I was also quite small for my age – I didn’t get a growth spurt until I was fourteen, at which point in just a few painful months I went from five feet to six feet tall. Before that, in comparison to the people I spent my days with I was tiny, and that gave them ample opportunities to bully me. The bullying happened day after day and year after year, and it never occurred to me to think that anything could be done about it by an authority figure. So I had to find my own way of addressing the problem, and the strategy I came up with was to become a teller of tales – a fabulist.

On the way to school, I might see a couple of cars barely avoid each other at an intersection; but by the time I got to school that had turned into a violent collision that left dead bodies sprawling out of the open windows of their automobiles. Certainly there would have been blood, perhaps a severed limb or two. All the way to school I would silently elaborate and edit the story, trying to find that sweet spot where the spectacular shakes hands with the believable. After a while lying became more normal to me than telling the truth. After all, what would be the point in telling the truth if you could make up something better? It made life always interesting.

Moreover, I discovered that the better I became at lying, and indeed the more consistently I lied, the more attention I got from my classmates. They wouldn’t be yanking my hair or punching me in the stomach as long as they were waiting to see how the story came out. It took me a very long time to break the habit of lying; it was only after I became a Christian, during my college years, that it dawned on me that this habit might be morally questionable. (Before that I had only considered the possible reputational damage of getting caught in a lie. My category was shame, not guilt.) And I’ve never broken the habit of internal fabrication. I still see ordinary everyday events and instinctively create a more dramatic narrative – I just don’t share that invented reality with other people.

One of the consequences of this history of fabulism, for me, has been an instinctive and unsuppressable skepticism towards stories told by other people. Whenever anyone writes about some extraordinary experience they’ve had – well, I simply don’t believe that it happened. I don’t think about it; I don’t consciously make a judgement. That’s just the immediate response that springs up in me wholly unbidden.

I remember being very surprised to learn that other people were surprised to learn that David Sedaris’s stories are mostly invented. I had never imagined that a single word of them was true. It never occurred to me to believe that he had sung the Oscar Mayer Wiener theme song in the voice of Bille Holiday to his music teacher, or that he had been Crumpet the Elf. Just the other day, I was reading an essay by Leslie Stephen, Virginia Woolf’s father, about an accident he had while hiking in the Swiss mountains and I assumed, unreflectively, that he had made up the whole thing, simply because for a long time that’s what I would have done.

I find that this skepticism is most intense – actually rising to the level of conscious disbelief – whenever I encounters writers talking about writing. Oh, how they love to narrate spectacular personal drama: extended periods of profound misery, depression, antisocial behavior, substance abuse, irrational and compulsive actions of a hundred kinds. You listen to their stories, and if you take them seriously, you think nothing could be more dramatic than being a writer. But I am a writer and I don’t believe a word of it.

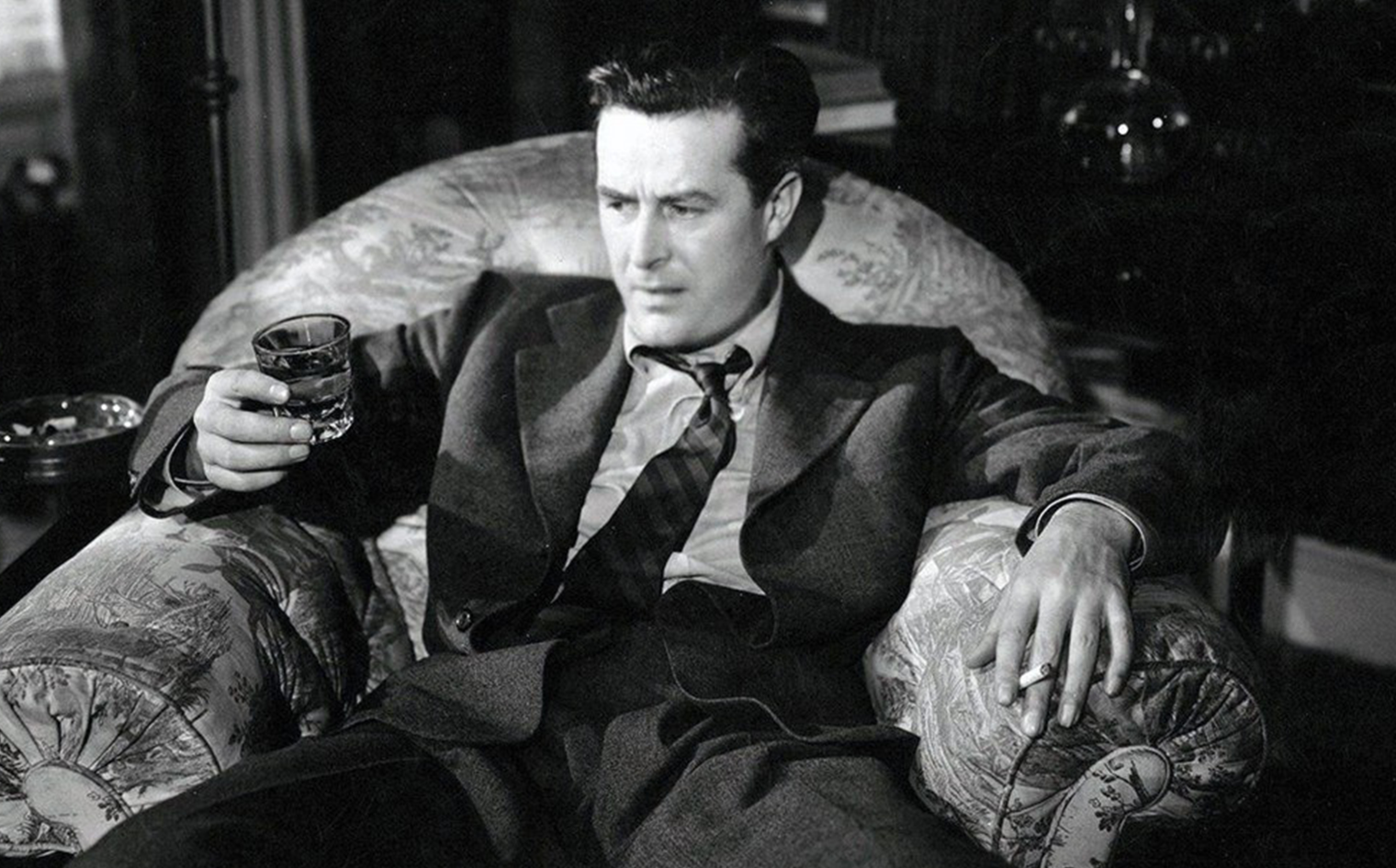

I don’t think that these people never get drunk, never abuse drugs, never suffer depression. What I cannot believe is that any of this behavior has anything to do with their creative process. I think their writing lives actually go something like this: They set an alarm for a reasonable hour of the morning, they get up and made themselves a cup of coffee, they browse through social media, and then they sat down to write, promising themselves a cinnamon roll or a smoke if they get through 1000 words. And they just do this most days. They’re like Ray Milland in The Lost Weekend, they can’t write until they drop a lit cigarette into their tumbler of rye to make it undrinkable. That’s how they work, I’m sure. I simply lack the capacity to assent to their more dramatic tales.

It’s possible, of course, that I’m wrong about all this, that my skepticism is unwarranted. And maybe that’s the price that I pay for being a reformed fabulist. I’ve lost my ability to trust other people’s stories, unless of course, they explicitly own them as fiction. As Sir Philip Sidney wrote more than four hundred years ago, “the poet” – by which he means the teller of tales – “never maketh any Circles about your imagination, to conjure you to believe for true, what he writeth … and therefore though he recount things not true, yet because he telleth them not for true, he lieth not.” And in turn is wholly believable.

But all that I told you at the outset about my own career as a fabulist? Every word is true. You believe me – don’t you?

UPDATE 2023-09-21: “Emotional truths.”