Mann's Joseph: 5

One of the most fascinating, and to me surprising, elements of Joseph and His Brothers is the way Mann leans into the simplest of mythical themes: descent and ascent. Down and up.

He does this in part because the biblical narrative virtually demands it. Joseph's family, as we have already noted, are herdsmen and people of the hills. The habitable portion of ancient Egypt, by contrast, is a long river valley. Therefore, one always goes down to Egypt. You hear this phrase over and over again in Genesis:

Gen.26:2 “And the LORD appeared unto him, and said, Go not down into Egypt; dwell in the land which I shall tell thee of.”

Gen.37:25 “And they sat down to eat bread: and they lifted up their eyes and looked, and, behold, a company of Ishmaelites came from Gilead with their camels bearing spicery and balm and myrrh, going to carry it down to Egypt.”

Gen.39:1 “And Joseph was brought down to Egypt; and Potiphar, an officer of Pharaoh, captain of the guard, an Egyptian, bought him of the hands of the Ishmaelites, which had brought him down thither.”

Gen.46:3 “And he said, I am God, the God of thy father: fear not to go down into Egypt; for I will there make of thee a great nation:

Num. 20:15 “Our fathers went down into Egypt, and we have dwelt in Egypt a long time; and the Egyptians vexed us, and our fathers.”

By contrast, one always goes up to Jerusalem:

1 Kings 12:28 “Whereupon the king took counsel, and made two calves of gold, and said unto them, It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem: behold thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt.”

Luke 18:31 "Then he took unto him the twelve, and said unto them, Behold, we go up to Jerusalem, and all things that are written by the prophets concerning the Son of man shall be accomplished.”

But this is not simply a matter of topographical measurement. Though the literal elevation of Jerusalem is around 2500 feet, many places in Israel stand higher — yet even from them, to go to Jerusalem is to go up:

Isaiah 2:3 “And many people shall go and say, Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of the LORD, to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem.”

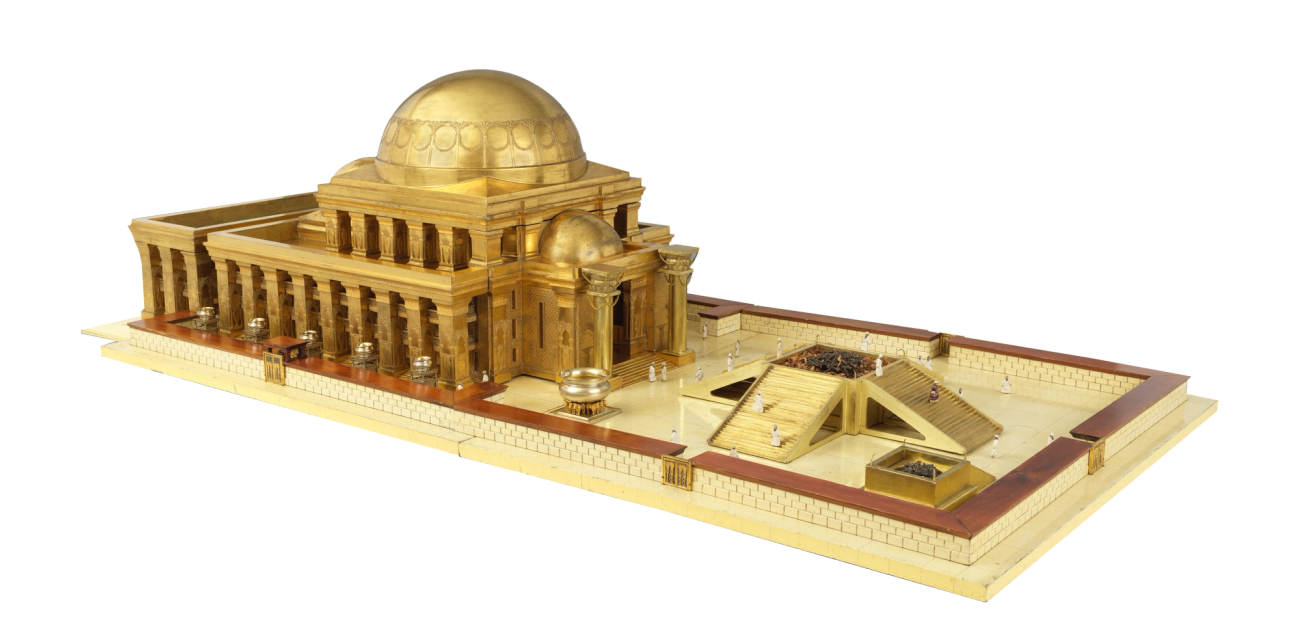

And if Jerusalem is spiritually the highest place, then Egypt is spiritually the lowest place, and this is not because of its elevation but because of its fascination with death and the underworld — its cult of Osiris.

In the introduction his famous and almost unimaginably influential translation of what he called the Egyptian Book of the Dead, E. A. Wallis Budge writes of the mysterious “new-comers from the East” who altered the primitive burial practices of the native Egyptians:

The indigenous peoples readily saw the advantage of brickbuilt tombs and of the other improvements which were introduced by the newcomers, and gradually adopted them, especially as they tended to the preservation of the natural body, and were beneficial for the welfare of the soul; but the changes introduced by the new-comers were of a radical character, and the adoption of them by the indigenous peoples of Egypt indicates a complete change in what may be described as the fundamentals of their belief. In fact they abandoned not only the custom of dismembering and burning the body, but the half savage views and beliefs which led them to do such things also, and little by little they put in their place the doctrine of the resurrection of man, which was in turn based upon the belief that the god-man and king Osiris had suffered death and mutilation, and had been embalmed, and that his sisters Isis and Nephthys had provided him with a series of amulets which protected him from all harm in the world beyond the grave, and had recited a series of magical formulae which gave him everlasting life; in other words, they embraced the most important of all the beliefs which are found in the Book of the Dead. The period of this change is, in the writer's opinion, the period of the introduction into Egypt of many of the religious and funeral compositions which are now known by the name of “Book of the Dead.”

So when Joseph — having been thrown down into a pit and then raised up out of the pit; his first descent and first rise — goes down into Egypt, he enters a world dominated by the Underworld, and by the god-king who rules it: one raised up as King of Egypt, then cast down into death, then raised up again as King of the Underworld.

The vertical oscillations of Osiris are then replicated by this stranger Joseph, who also rises and falls repeatedly: once he gets to Egypt, as a mere slave, he is raised up by Potiphar, and then cast down into prison, and then raised up by Akhenaten. The way up is the way down, and the way down may prove to be but a stage of one’s ascent. Osiris knows this, and Joseph learns it — it is what he knows that his herdsman father Jacob does not.

In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, three movements are repeatedly described: going into the underworld, passing through it, and coming forth from it. Mann is obsessed by these movements, especially, though not only, as they are manifest in the life of Joseph. It is said that the god Thoth is the scribe of the underworld, though he does not remain there. He always passes through, as the messenger and mediator must. And one aspect or element of Joseph's role as mediator is, through his influence on Akhenaten, to turn the minds of the Egyptians away from the underworld and towards the sun — even if this turn is merely one oscillation among many, even if, in the end, the sun itself cannot hold our attention forever.

(Many centuries later, these lessons would be learned with great difficulty by a Galilean fisherman named Simon Peter. On the Mount of Transfiguration he declares: “Lord, it is good that we are here. If you wish, I will make three tents here, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah.” But he cannot stay there. There are many more vertical oscillations to come, first for his Master, and then for him.)