to be a pilgrim

I’ve been teaching The Pilgrim’s Progress, something that always gives me great joy. I find it simply wonderful that so utterly bonkers a book was so omnipresent in English-language culture (and well beyond) for so long. You couldn’t avoid it, whether you loved it — as George Eliot’s Maggie Tulliver did, and lamented the sale of the family’s copy: “I thought we should never part with that while we lived” — or found it puzzling, as Huck Finn did when he recalled the books he read as a child: “One was ‘Pilgrim's Progress’, about a man that left his family it didn't say why. I read considerable in it now and then. The statements was interesting, but tough.”

One of the “tough” things about the “statements” is the way they veer from hard-coded allegory to plain realism, sometimes within a given sentence. One minute Moses is the canonical author of the Pentateuch, the next he’s a guy who keeps knocking Hopeful down. But the book is always psychologically realistic, to an extreme degree. No one knew anxiety and terror better than Bunyan did, and when Christian is passing through the Valley of the Shadow of Death and hears voices whispering blasphemies in his ears, the true horror of the moment is that he thinks he himself is uttering the blasphemies. (The calls are coming from inside the house.)

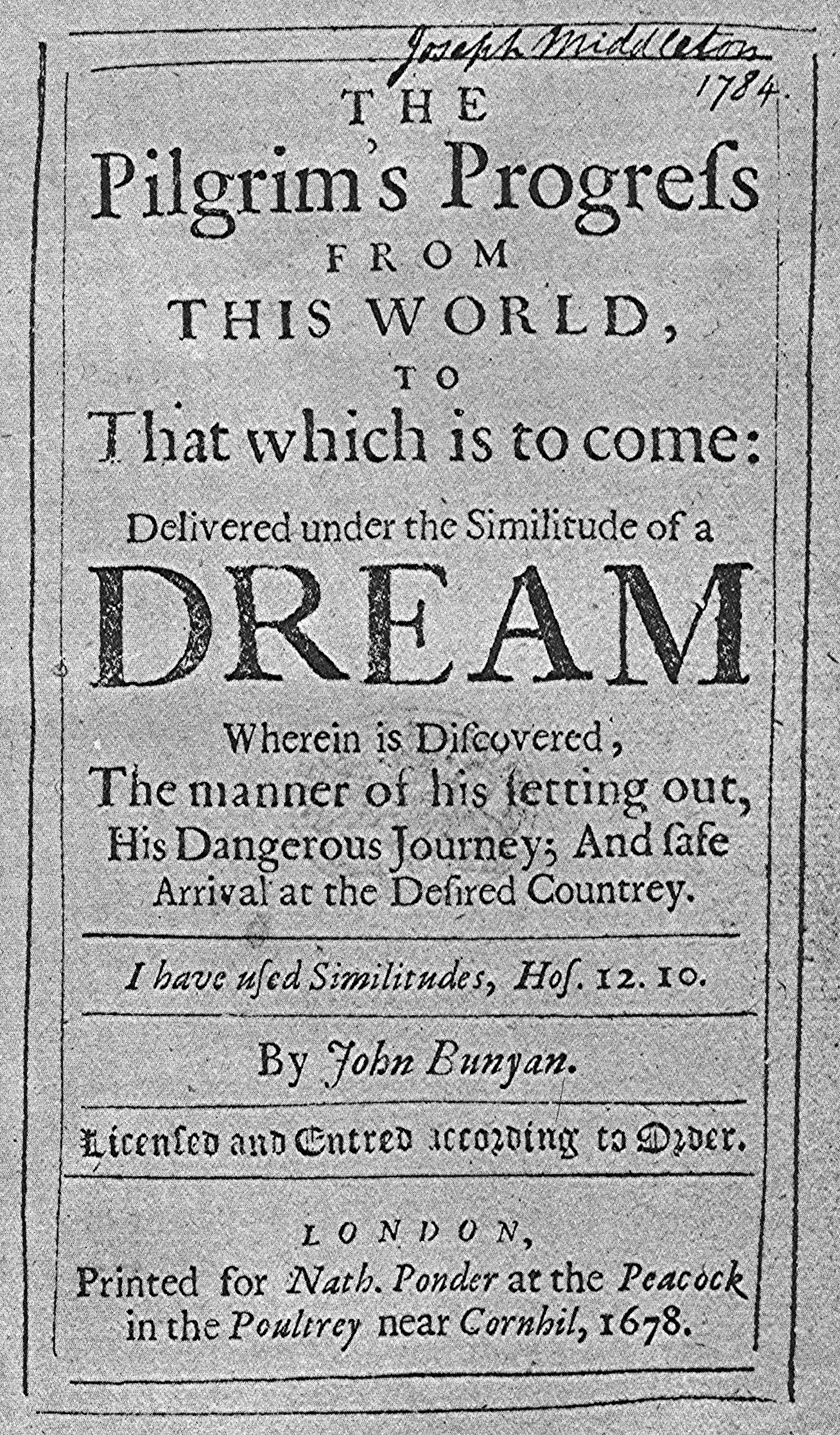

It seems likely that the last major cultural figure to acknowledge the power of Bunyan’s book is Terrence Malick, who begins his movie Knight of Cups with a voice declaiming the full title of the book: “The pilgrim's progress from this world to that which is to come, delivered under the similitude of a dream; wherein is discovered the manner of his setting out, his dangerous journey, and safe arrival at the desired country.”

Those words are uttered by John Gielgud, because they are taken from a 1990 performance of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s The Pilgrim’s Progress: A Bunyan Sequence, which is a work that Vaughan Williams wanted to compose for his whole life, but only got to near his life’s end: it is his final operatic composition. And it’s wonderful.

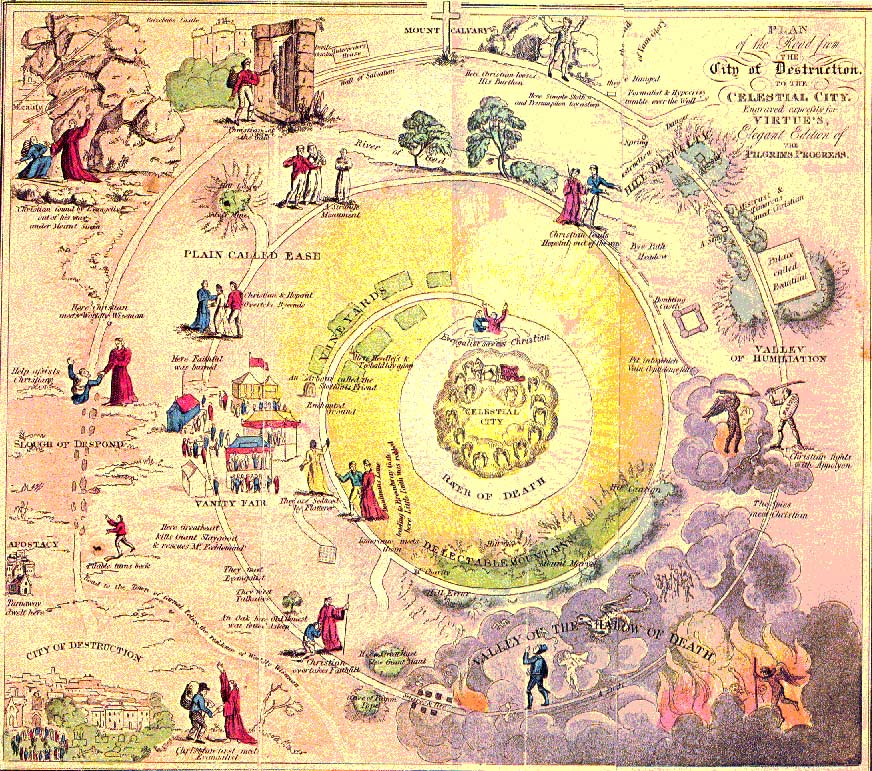

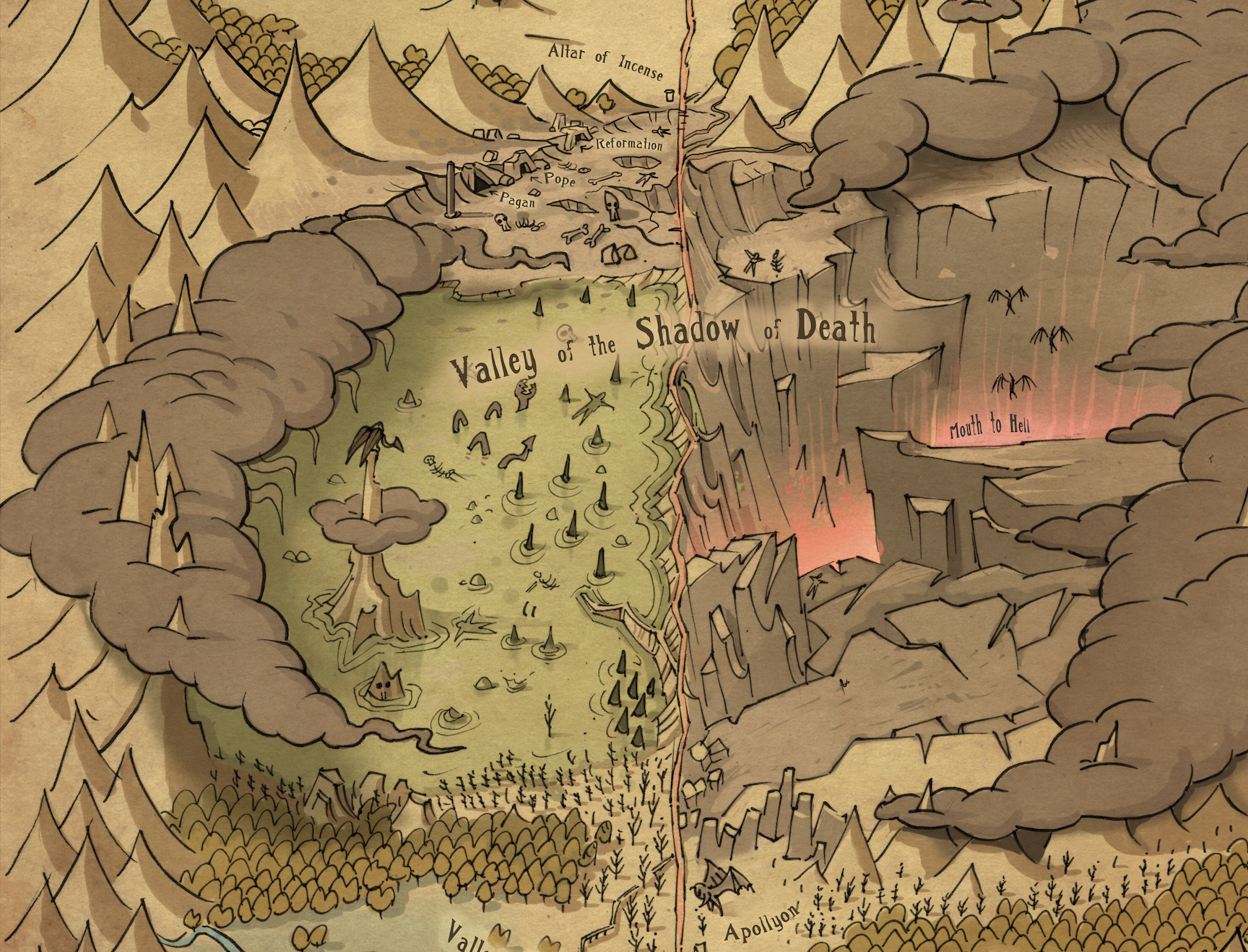

The Pilgrim’s Progress is almost always illustrated, and prominent among those illustrations are maps. Here’s a post about those maps. From that post I learned that Garrett Taylor — an artist and animator who has worked for Pixar and on The Wingfeather Saga TV series — has mapped The Pilgrim’s Progress is four prints that you can buy here. I bought them and had them framed and they now adorn a wall of our house. I stop to look at them three or four times a day.

It would be wrong for me to post the full-resolution images here, but I think I can risk one portion of one image:

Now, if Mr. Taylor can just convince Pixar to film the whole book….