Guadalcanal: 3

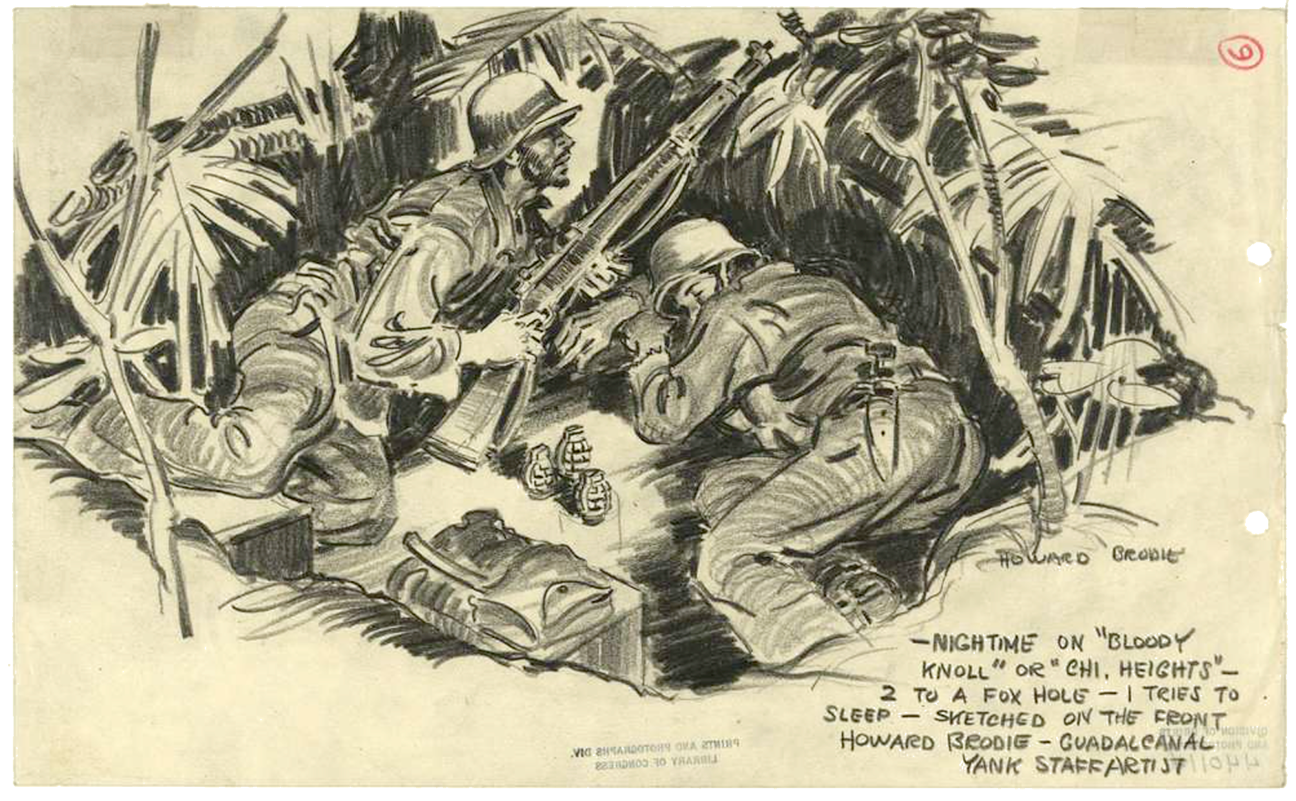

The above is a drawing by Howard Brodie, an artist James Jones much admired.

The distinctive way the Allied commanders organized the campaign for Guadalcanal, coupled with certain features intrinsic to island warfare, shaped the structure of Jones’s The Thin Red Line. Here’s how the novel begins:

The two transports had sneaked up from the south in the first graying flush of dawn, their cumbersome mass cutting smoothly through the water whose still greater mass bore them silently, themselves as gray as the dawn which camouflaged them. Now, in the fresh early morning of a lovely tropic day they lay quietly at anchor in the channel, nearer to the one island than to the other which was only a cloud on the horizon. To their crews, this was a routine mission and one they knew well: that of delivering fresh reinforcement troops. But to the men who comprised the cargo of infantry this trip was neither routine nor known and was composed of a mixture of dense anxiety and tense excitement.

In this respect the story of these soldiers resembles the Normandy invasion: it begins with a sea crossing. You must get on a ship and traverse the ocean to get to the place where you will fight.

But the attackers on D-Day in Normandy didn’t finish their war that way, not collectively anyway. Of course, some of them returned the way they came; but many others pushed deeper and deeper into Europe, and when they were done, made their way back home by airplane, or in transport ships with highly miscellaneous passengers.

What’s distinctive about The Thin Red Line is that C-for-Charlie Company travels to the island on a ship and then step onto the beach from landing craft — and then when it is relieved it returns in precisely the way it came. (“Ahead of them the LCIs waited to take them aboard, and slowly they began to file into them to be taken out to climb the cargo nets up into the big ships.”) It’s like entering and leaving a gladiatorial arena, except that there are these long sea journeys, crossings of empty liminal space, a space that radically separates what happens on the island from everything else in life, before and after. It’s more like Purgatory, then, than an arena — except for those who die. For them, I suppose, it’s Hell.

That some of them die while others survive means that C-for-Charlie Company is not precisely the same on its arrival and its departure. But the way Jones tells his story, the deaths are not presented as the deaths of individual whole persons but rather as the loss of appendages. Jones repeatedly speaks of the Company as a single entity: “But before that happened the whole of C-for-Charlie had gotten blind, crazy drunk in a wild mass bacchanalian orgy which lasted twenty-eight hours and used up all the available whiskey….” “Meanwhile back at the bivouac C-for-Charlie was still trying desperately to solve its liquor shortage.” When the Company comes across a dead soldier: “D Company had found him while pursuing the Japanese patrol and had placed him on the ledge behind C-for-Charlie for safekeeping at a time when C-for-Charlie was too engrossed in its firing to notice….” When stretcher-bearers take the dead man away: “C-for-Charlie had watched all this action wide-eyed and with sheepish faces.” One entity that happens to have many faces.

All of this is deeply relevant to the film Terrence Malick would make from James Jones’s novel.