2024

- A work of art can largely confirm the expectations of those who encounter it, largely thwart those expectations, or touch any point between those extremes. This is true of all the arts, but for present purposes I will speak only of fiction.

- These expectations can be of many kinds, but the most commonly invoked expectation involves difficulty: How hard-to-track, hard-to-comprehend do we expect and want a book to be?

- The reader who demands that all of his or her expectations be met is often called a lowbrow reader; the writer whose work habitually meets such readers’ expectations is often called a lowbrow writer.

- The reader who craves surprise, excess, extremity, who is impatient with work that confirms typical expectations, is often called a highbrow reader; the writer whose work consistently violates norms and transgresses standards is often called a highbrow writer.

- N.B.: Higher-browed readers often want to have their aesthetic expectations challenged, but not their moral ones. Almost no one wants that. (But they get it sometimes, from some writers. George Eliot and Vladimir Nabokov are good examples — I’ll write about them, in this regard, one day.)

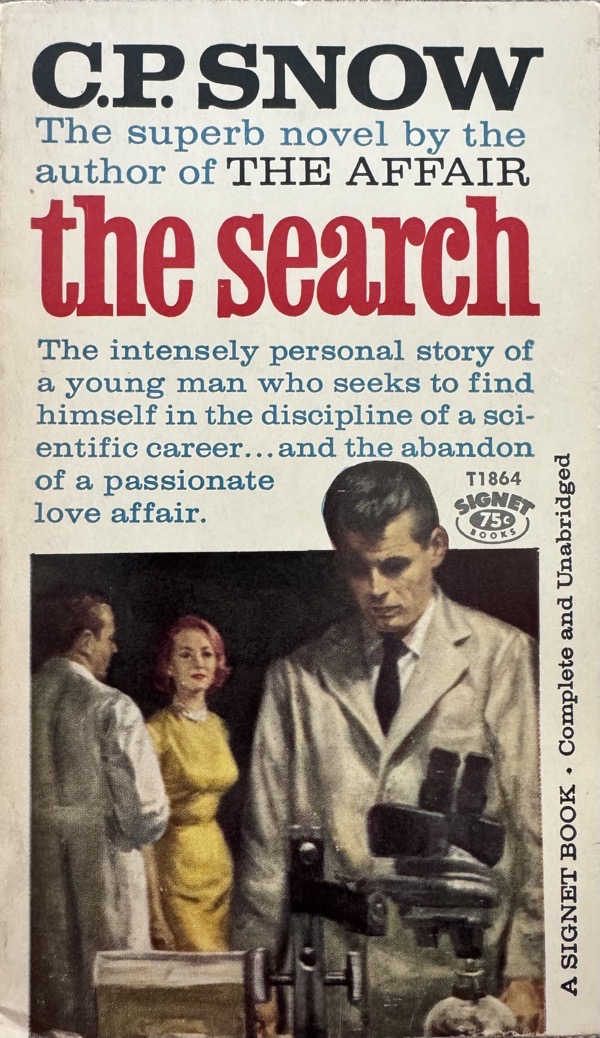

- “Highbrow,” “middlebrow,” and “lowbrow” are all characteristically pejorative terms, meant to insult, though in some cases (e.g. the piece by Woolf above) a writer will claim and even treasure the insult. See for comparison the history of such words as “Quaker” and “Methodist.” If Virginia Woolf does not think that your novel sufficiently resists your readers’ expectations, she will call you and your readers middlebrows; Graves and Hodges in the same circumstance will call you and your readers lowbrows. (They don’t mention C. P. Snow in their book, but if they had they’d probably have called him a lowbrow writer, but something like The Search is clearly meant for the educated reader.)

- The three brow-terms are most commonly used by people who are or believe themselves to be highbrows, though they may dislike that language and (implicitly or explicitly) put ironic scare-quotes around it.

- Even the most challenging writer will not always want to read works that constantly challenge or repudiate his or her expectations. Auden used to say that great masterpieces demand so much of their readers that you simply can’t take one on every day, not without either trivializing the experience or exhausting yourself.

- It is characteristic of highbrows’ use of these distinctions — see the Woolf letter quoted above and T. S. Eliot’s encomium to the music-hall entertainer Marie Lloyd, which employs the related socio-economic terms “aristocrat,” “middle-class,” and “worker” — that they articulate some alliance of themselves and the lowbrows against the middlebrow.

- Lowbrow readers do not know, and if they knew would not care, about this supposed alliance.

- Middlebrow readers and writers alike are often aware of the disdain of them felt by highbrows, and may respond either by defensiveness or mockery. (Think of Liberace’s famous response to his critics’ scorn for his music: “I cried all the way to the bank.” Funny to think of that line having a known origin, but it does.)

- For a long time now there has been no genuine lowbrow reading. Those who insist on all their expectations being fulfilled can get that hit much more efficiently through movies, TV, Instagram, TikTok, etc.

- The brow-discourse is conceptually distinct from, but overlaps considerably with, genre-discourse. For instance, detective novels that adhere strictly to the conventions of the genre — the Ellery Queen stories, for instance — will often be called lowbrow, while those that frequently deviate from the conventions — the later novels of P. D. James, for instance, or Sayers’s Gaudy Night — may get called “highbrow” or, more likely, “literary fiction.”

- The tripartite brow-discourse is much less useful than a more nuanced and more detailed account of readerly expectations, one which is sensitive to the ways different genres can generate different sets of expectations, and respond to those expectations in diverse ways.

- Sayers specifies what pages were torn from the book — but I don’t have access to the edition that Sayers had read, which I assume was the first hardcover edition, so I don’t know what exactly was excised, but I suspect that it was the part where Miles admits his mistake. (The whole business is a flaw in Sayers’s plot, because it’s impossible to imagine the Responsible Party having read Snow’s book and known which pages to tear out; but DLS clearly was determined to get a discussion of The Search into her own novel, so she found a way.)

- As it happens, this is Snow’s most autobiographical novel: what happened to Miles also happened to him. He began his career as a chemist, and wrote a paper (published in Nature) which was then discovered to contain an embarrassing mistake — upon which he abandoned his work as a scientist and became a novelist and bureaucrat.

- The man who has falsified the data, Sheriff, is one of Miles’s oldest friends.

- Miles got Sheriff his current job and has been guiding his research, trying to keep him on the straight and narrow — he’s a feckless fellow, and a habitual liar, but Miles had hoped that he was ready to reform.

- Sheriff had promised Miles, and also his own wife, that he was working on a safe project when he was in fact working on a high-risk, high-reward one — one he thought likely to lead to a prestigious position that, now that the paper has been published, he is indeed about to be offered.

- Miles has a sense of responsibility for Sheriff because he had hoped to hire him for a position at the aforementioned Institute, but gave up on the idea when he realized that his own position was compromised. He thinks perhaps he should have pushed harder for Sheriff anyway.

- Early in his career Miles had had the opportunity to consciously fudge data himself, and seriously considered it — he thought that he might eventually be found out, but only after achieving a brilliant career from which summit he could just say “Whoops, I made a mistake” — but instead abandoned the research project. He thought, though, that in the future he would have compassion for any scientist who succumbed to a similar temptation.

- And most important of all, Sheriff is married to Audrey, Miles’s former lover, for whom, though he himself is now happily married, he cherishes a strong and lasting tendresse — despite the fact that Sheriff basically stole her affections while Miles was abroad.

Laura Brown, The Great Lakes of North America

back to the brows

After reading various writings about the brows — including, first of all, this unsent letter by Virginia Woolf and this 1949 essay by Russell Lyne, I find myself impatient and wanting to cut to the chase. I’ll come back to these matters later when I’ve had more time to think them over, but in the meantime, some Theses:

UPDATE 2024–05–27: It suddenly occurs to me that I have been confusing two quite different things: the three-brow distinction as a way of talking specifically about reading books and as a way of talking about culture then as a whole. If you’re talking about reading, then of course there are lowbrow readers, lowbrow books, etc. But if you’re talking broadly about culture, then in an age when the popularity of movies, TV, and social media is at least an order of magnitude — I use that term with care; most people use it to mean “a whole lot” — I repeat, at least an order of magnitude greater than the popularity of reading, then anyone who reads books at all is ipso facto a middlebrow.

UPDATE 2024-06-05: I have received a salutary word of criticism from my friend Francis Spufford:

It is slightly nerve-wracking saying this, Professor Jacobs, but you are uncharacteristically misreading the Woolf. Yes, she's a vile old snob in literary as much as in social terms. But I don't think you can adduce what she says here about the ‘common reader’ as proof of that. To my ear, she's being ironic throughout. She says, with stagey astonishment, that the common reader fails to measure up to proper critical standards, insisting on reading for such low satisfactions as pleasure, amusement, and a sense of meeting real human beings. She observes, as if baffled, that the survival or otherwise of literature over the long term is determined by the reputation of a work among these amateurs, and not among professors or theoreticians at all. How ghastly! Just for once, I'm sure the irony here means that Woolf is putting herself on the side of what's common. There is a hole on her snobbery, a subject on which she feels like an insurgent rather than a possessor, and it's to do with her lack of a university education. Unlike Sayers at Somerville, Virginia Stephen did all her reading at home, devising her own critical standards based on her own reactions. She is a common reader, by her own lights. Indeed she publishes two books of critical essays called The Common Reader and The Common Reader 2. She's claiming the right to read Cervantes for fun, rather than the right to borrow three romances a week from the Boots Circulating Library, but it's still a claim to centre pleasure. Virginia on the barricades! Virginia 'Che’ Woolf!I think Francis is almost wholly right here, though I do believe Woolf’s irony is accompanied by snobbery. Anyway, criticism taken gratefully on board, to be deployed later.

I just posted a new letter to my BMAC supporters.

Playing this morning: Khruangbin’s A LA SALA. ♫

This from Austin Kleon is great:

One of the reasons I didn’t connect with writer Nicholson Baker’s recent book about learning to draw, Finding a Likeness, is that he couldn’t seem to enjoy the process of drawing unless the drawing resulted in what he felt was visual accuracy. I remember watching him learn to draw on Twitter and Instagram and noticing a point at which he seemed to get much better, and saying so. Upon reading the book, I realized that point was when he started tracing photographs to begin his drawings….

I admire Baker greatly as a fiction writer, and we have the same general idea about the value of drawing as a way of noticing the world. But how you get there… that’s where we differ wildly. The last way I personally want to spend my time drawing is by taping a piece of paper to a computer screen and tracing a digital image with a pencil. I want drawing to take me out into the world, away from my screens and get me to look at it with my own eyeballs.

It’s pub day for my critical edition of Auden’s The Shield of Achilles!

Our new bee attractor.

Doug Stowe: “My proposal … was as follows: Start with the basic elements from Greek philosophy — earth, air, fire, and water — and divide the incoming freshman class according to their elemental inclinations. Then provide concrete activities for student engagement along those lines.”

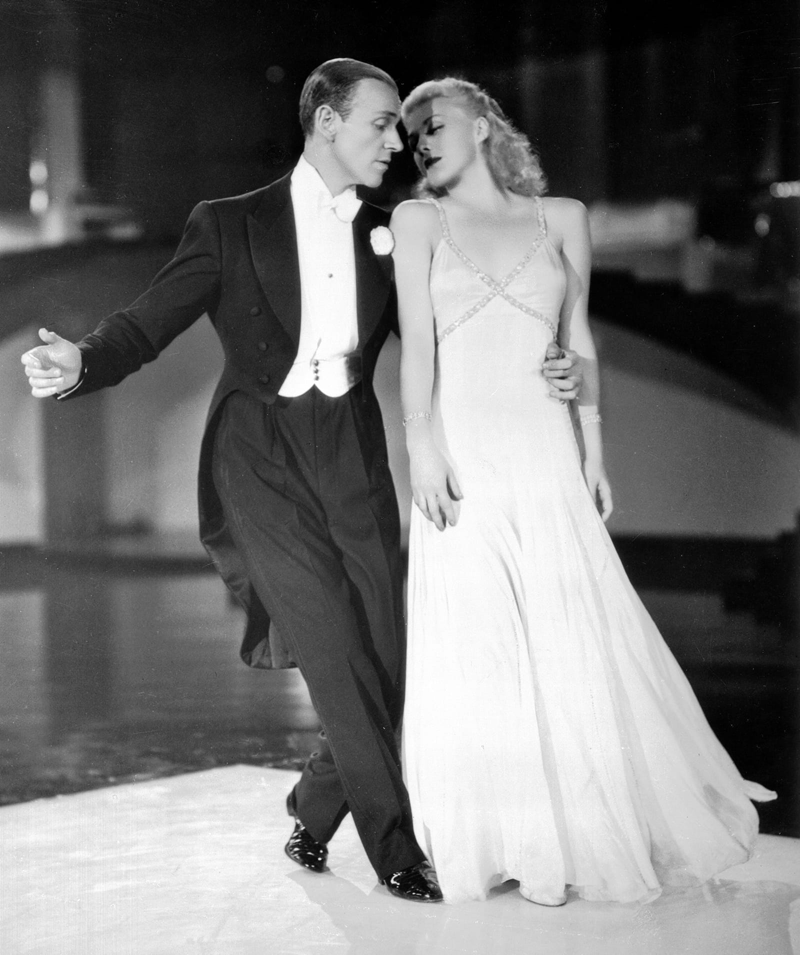

elegance personified (really)

Last night Teri and I watched Swing Time, and afterwards played a little game: We went back to the dance scenes and tried to pause at instants when Astaire and Rogers didn’t look elegant. Couldn’t do it. At every moment they are balanced and poised, they’re perfect images of grace.

On two novels that describe scientific/scholarly integrity – or the lack thereof.

the integrity of science

I haven’t forgotten about middlebrow matters, but right now my mind is on something else. Something related, though.

Readers of Gaudy Night (1935) will recall — stop reading if you haven’t read Gaudy Night and don’t want any spoilers — that the plot hinges on an event that occurred some years before the book’s present-day: a (male) historian fudged some evidence and a (female) historian caught him at it and reported the malfeasance, which led to his losing his job. Late in the book, but before the full relevance of this event to the plot has been revealed, there’s a conversation about scholarly integrity, which I will now drop into the middle of:

“So long,” said Wimsey, “as it doesn't falsify the facts. But it might be a different kind of thing. To take a concrete instance — somebody wrote a novel called The Search — “

“C. P. Snow,” said Miss Burrows. “It's funny you should mention that. It was the book that the — ”

“I know,” said Peter. “That's possibly why it was in my mind.”

A person has been vandalizing Shrewsbury College and a copy of that novel, with certain pages torn out, has been found. The novel, by the way, appeared in 1934, around the time that Sayers began writing Gaudy Night. It would be interesting to know whether it was the direct inspiration for her story, or whether she read it after some elements were already in place. I hope to find out more about that.

And by the way, I am going to be spoiling that novel far more thoroughly than I will spoil Gaudy Night — but it’s not one that many people read, these days.

“I never read the book,” said the Warden.

“Oh, I did,” said the Dean. “It's about a man who starts out to be a scientist and gets on very well till, just as he's going to be appointed to an important executive post, he finds he's made a careless error in a scientific paper. He didn't check his assistant's results, or something. Somebody finds out, and he doesn't get the job. So he decides he doesn't really care about science after all.”

“Obviously not,” said Miss Edwards. “He only cared about the post.”

Neither the Dean, who has read the book, nor Miss Edwards, who hasn’t, is quite accurate. The scholar, whose name is Arthur Miles, probably would have gotten the post even without the paper; but it’s perfectly possible that he rushed the paper, failed to be appropriately self-critical, because he knew that the vote for the Director of a new scientific institute would be coming soon. Miles doesn’t know; he can’t be sure; maybe he would’ve made the mistake anyway. But in any case, as soon as he is told that there’s a problem with his paper, he runs the numbers again, sees the error, and immediately admits that he was wrong.

Let me pause for two digressions:

Now, back to Gaudy Night:

“The point about it,” said Wimsey, “is what an elderly scientist says to him. He tells him: ‘The only ethical principle which has made science possible is that the truth shall be told all the time. If we do not penalize false statements made in error, we open up the way for false statements by intention. And a false statement of fact, made deliberately, is the most serious crime a scientist can commit.’ Words to that effect. I may not be quoting quite correctly.“

Wimsey’s summary is a good one. This is indeed what the “elderly scientist,” a man named Hulme, says to him. And Miles does not disagree. What’s more on his mind, though, is the picture of his future laid out for him by another senior scientist:

“You’ve got to work absolutely steadily, without another suspicion of a mistake. You’ve got to let yourself be patronised and regretted over. You’ve got to get out of the limelight. Then in three or four years, you’ll be back where you were; though it will be held up against you, one way and another, for longer than that. It will delay your getting into the Royal [Society], of course. That can’t be helped. You’ll have a lean time for a while; but you’re young enough to get over it.”

Faced with this prospect, Miles realizes that he could only manage all this (“Watching the dullards gloat. Working under Tremlin. Having every day a reminder of the old dreams”) if he had a genuine devotion to science. But: “It occurred to me I had no devotion to science.”

N.B.: the point is not that the event has taken away his devotion to science, but rather, “I am not devoted to science, I thought. And I have not been for years, and I have kept it from myself till now.” The revelation of his error leads to a revelation of what had been true about him all along: “There were so many signs going back so far, if I had let myself see, if it had been convenient to see.” Indeed, it now becomes clear to him that his desire to become the director of a scientific institute — an administrative position, not one that would involve him directly in research — precisely because on some unconscious level he didn’t want to be a scientist any more: “I had thrown myself into human beings — to escape the chill when my scientific devotion ended.”

It should be clear, then, that “he decides he doesn’t really care about science after all” is not an adequate explanation of what happens.

But there’s also a twist in the tail of this story, which in Gaudy Night Sayers calls attention to:

“In the same novel,” said the Dean, “somebody deliberately falsifies a result — later on, I mean — in order to get a job. And the man who made the original mistake finds it out. But he says nothing, because the other man is very badly off and has a wife and family to keep.”

”These wives and families!“ said Peter.

”Does the author approve?“ inquired the Warden.

”Well,“ said the Dean, ”the book ends there, so I suppose he does.”

Or does he? And is that an accurate description of the case? Several facts here are relevant:

The Search is not a great novel, but this is perhaps its best element: the faithful portrayal of Miles’s complex and ever-shifting and deeply human responses to Sheriff’s lying. (It reminds me a bit of the greatest scene of this kind I know, the moment in Middlemarch when Lydgate has to decide how to vote for the chaplaincy of a new hospital. I wrote about that thirty years ago [!!] near the end of this essay.)

On the one hand, he knows exactly what Sheriff did and why:

I had no doubts at all. It was a deliberate mistake. He had committed the major scientific crime (I could still hear Hulme’s voice trickling gently, firmly on).

Sheriff had given some false facts, suppressed some true ones. When I realised it, I was not particularly surprised. I could imagine his quick, ingenious, harassed mind thinking it over. For various reasons, he had chosen this problem; it would not take so much work, it would be more exciting, it might secure his niche straight away. … But I must not know, half because he was a little ashamed, half because I might interfere. So [his research assistant] and Audrey must, for safety’s sake, also be deceived.

All this he would do quite cheerfully. The problem began well. … Then he came to that stage where every result seemed to contradict the last, where there was no clear road ahead, where there seemed no road ahead at all. There he must have hesitated. On the one hand he had lost months, there would be no position for years, he would have to come to me and confess; on the other his mind flitted round the chance of a fraud.

There was a risk, but he might secure all the success still. I scarcely think the ethics of scientific deceit troubled him; but the risk must have done. For if he were found out, he was ruined. He might keep on as a minor lecturer, but there would be nothing ahead.

Miles does not excuse Sheriff at any point; he knows that the man’s dishonesty is habitual, perhaps pathological. But he also knows that Sheriff and Audrey have reached a certain accommodation in their marriage, that Audrey understands who her husband is but loves him and needs him anyway. Miles writes a letter that would expose and run Sheriff, and then, realizing that it would also ruin Audrey, …

I shall not send the letter, I was thinking. Let him win his gamble. Let him cheat his way to the respectable success he wants. He will delight in it, and become a figure in the scientific world; and give broadcast talks and views on immortality; all of which he will love. And Audrey will be there, amused but rather proud. Oh, let him have it.

For me, if I do not send the letter, what then? There was only one answer; I was breaking irrevocably from science. This was the end, for me. Ever since I left professionally, I had been keeping a retreat open in my mind; supervising Sheriff had meant to myself that I could go back at any time. If I did not write I should be depriving myself of the loophole. I should have proved, once for all, how little science mattered to me.

There were no ways between. I could have held my hand until he was elected, and then threatened that either he must correct the mistake, or I would; but that was a compromise in action and not in mind. No, he should have his triumph to the full. Audrey should not know, she had seen so many disillusions, I would spare her this.

The human wins out over the scientific. Maybe, Arthur thinks, it always does. But Gaudy Night shows that sometimes the scientific — in the sense of a strict commitment to the sacredness of honest research — can sometimes have its own victories. And Gaudy Night also suggests that the choices might not be as stark as Snow’s story suggests. More on that in another post.

A good introduction to the Mondragón model. We desperately need a version of this somewhere in the USA, just to demonstrate that business-as-usual is not the only way of doing business.

Related: the Uncovering Roman Carlisle site is fascinating.

Apparently the place for relics of Roman Britain is the Carlisle Cricket Club.

P.S.A.

A number of people have asked me for my thoughts about the current university campus protests. I have very few. As the novelist John Barth said when asked why he hadn’t been involved in the anti-war protests of the Sixties, “the fact that the situation is desperate doesn’t make it any more interesting.” People who aren’t interested in learning (or in politics either, in any meaningful way) have thrown a monkey wrench into the works of universities that don’t care about teaching them. Not my bag.

I think this Ross Douthat column is good, though. I’m grateful that Ross writes about things like this so I can write about very different things.

And finally, the Rio Grande as it emerges from the Santa Elena Canyon (whose walls reach 1500 feet in height) at the western end of the park.

The previous photo was of the Chisos Mountains in the center of the park; this one of the Rio Grande at the park’s eastern boundary.