The last official lighthouse keeper in the United States is named Sally Snowman.

So far I have five posts on Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers:

Mann's Joseph: 5

One of the most fascinating, and to me surprising, elements of Joseph and His Brothers is the way Mann leans into the simplest of mythical themes: descent and ascent. Down and up.

He does this in part because the biblical narrative virtually demands it. Joseph's family, as we have already noted, are herdsmen and people of the hills. The habitable portion of ancient Egypt, by contrast, is a long river valley. Therefore, one always goes down to Egypt. You hear this phrase over and over again in Genesis:

Gen.26:2 “And the LORD appeared unto him, and said, Go not down into Egypt; dwell in the land which I shall tell thee of.”

Gen.37:25 “And they sat down to eat bread: and they lifted up their eyes and looked, and, behold, a company of Ishmaelites came from Gilead with their camels bearing spicery and balm and myrrh, going to carry it down to Egypt.”

Gen.39:1 “And Joseph was brought down to Egypt; and Potiphar, an officer of Pharaoh, captain of the guard, an Egyptian, bought him of the hands of the Ishmaelites, which had brought him down thither.”

Gen.46:3 “And he said, I am God, the God of thy father: fear not to go down into Egypt; for I will there make of thee a great nation:

Num. 20:15 “Our fathers went down into Egypt, and we have dwelt in Egypt a long time; and the Egyptians vexed us, and our fathers.”

By contrast, one always goes up to Jerusalem:

1 Kings 12:28 “Whereupon the king took counsel, and made two calves of gold, and said unto them, It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem: behold thy gods, O Israel, which brought thee up out of the land of Egypt.”

Luke 18:31 "Then he took unto him the twelve, and said unto them, Behold, we go up to Jerusalem, and all things that are written by the prophets concerning the Son of man shall be accomplished.”

But this is not simply a matter of topographical measurement. Though the literal elevation of Jerusalem is around 2500 feet, many places in Israel stand higher — yet even from them, to go to Jerusalem is to go up:

Isaiah 2:3 “And many people shall go and say, Come ye, and let us go up to the mountain of the LORD, to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem.”

And if Jerusalem is spiritually the highest place, then Egypt is spiritually the lowest place, and this is not because of its elevation but because of its fascination with death and the underworld — its cult of Osiris.

In the introduction his famous and almost unimaginably influential translation of what he called the Egyptian Book of the Dead, E. A. Wallis Budge writes of the mysterious “new-comers from the East” who altered the primitive burial practices of the native Egyptians:

The indigenous peoples readily saw the advantage of brickbuilt tombs and of the other improvements which were introduced by the newcomers, and gradually adopted them, especially as they tended to the preservation of the natural body, and were beneficial for the welfare of the soul; but the changes introduced by the new-comers were of a radical character, and the adoption of them by the indigenous peoples of Egypt indicates a complete change in what may be described as the fundamentals of their belief. In fact they abandoned not only the custom of dismembering and burning the body, but the half savage views and beliefs which led them to do such things also, and little by little they put in their place the doctrine of the resurrection of man, which was in turn based upon the belief that the god-man and king Osiris had suffered death and mutilation, and had been embalmed, and that his sisters Isis and Nephthys had provided him with a series of amulets which protected him from all harm in the world beyond the grave, and had recited a series of magical formulae which gave him everlasting life; in other words, they embraced the most important of all the beliefs which are found in the Book of the Dead. The period of this change is, in the writer's opinion, the period of the introduction into Egypt of many of the religious and funeral compositions which are now known by the name of “Book of the Dead.”

So when Joseph — having been thrown down into a pit and then raised up out of the pit; his first descent and first rise — goes down into Egypt, he enters a world dominated by the Underworld, and by the god-king who rules it: one raised up as King of Egypt, then cast down into death, then raised up again as King of the Underworld.

The vertical oscillations of Osiris are then replicated by this stranger Joseph, who also rises and falls repeatedly: once he gets to Egypt, as a mere slave, he is raised up by Potiphar, and then cast down into prison, and then raised up by Akhenaten. The way up is the way down, and the way down may prove to be but a stage of one’s ascent. Osiris knows this, and Joseph learns it — it is what he knows that his herdsman father Jacob does not.

In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, three movements are repeatedly described: going into the underworld, passing through it, and coming forth from it. Mann is obsessed by these movements, especially, though not only, as they are manifest in the life of Joseph. It is said that the god Thoth is the scribe of the underworld, though he does not remain there. He always passes through, as the messenger and mediator must. And one aspect or element of Joseph's role as mediator is, through his influence on Akhenaten, to turn the minds of the Egyptians away from the underworld and towards the sun — even if this turn is merely one oscillation among many, even if, in the end, the sun itself cannot hold our attention forever.

(Many centuries later, these lessons would be learned with great difficulty by a Galilean fisherman named Simon Peter. On the Mount of Transfiguration he declares: “Lord, it is good that we are here. If you wish, I will make three tents here, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah.” But he cannot stay there. There are many more vertical oscillations to come, first for his Master, and then for him.)

St. Pancras Station has the best Christmas tree evar

Land acknowledgements are widely derided as farces and, generally, I agree that they are. When Microsoft sets aside time to open its internal communications with a list of Coast Salish peoples that “since time immemorial” occupied the area that is now the company’s headquarters, this does not imply that they intend to return the land to the indigenous people who once lived on it, or even that they will do anything else substantive for their benefit. It’s just marketing, much as it is when REI does it at the start of a video urging its employees not to unionize. And yet, there has been quite a bit of surprise this month at the number of people who, when they talk about “decolonization” and the idea that Palestine should extend “from the river to the sea,” appear to literally mean that the seven million Jewish “settler-colonialists” who live there ought to be eliminated from the area, whether through death or expulsion.

Any argument that “decolonization” is a moral imperative requiring the removal of Jews from Israel applies equally to the non-indigenous population of the United States. Actually, it applies more clearly, given the ambiguity about who was really in the Holy Land first and the clear fact that Coast Salish people were in (what is now) Redmond, Washington before white people. Is it a good idea for non-indigenous Americans to adopt a rhetorical framework that implies we ought to give our land back and leave our home country on the basis of the idea that everyone knows we don’t really mean it?

Of course it’s a good idea! It’s not like anyone thinks such people are serious about anything. As Barro says, it’s marketing.

There’s a faction of the left — how large a faction I have no idea — obsessed with the idea that political sins must be paid for, though always exempting themselves from the responsibility of payment. I think of Albert Camus’s paraphrase of the attitude of the lefties of Metropolitan France to the Algerian pieds-noirs: “Go ahead and die; that’s what we deserve!” To all these people desperate to find someone else to bear their sins, I want to say: Have you ever heard of Jesus?

A fantastic post by my buddy Austin Kleon on the artists Robert Irwin and David Hockney and the writer Lawrence Wechsler. The themes Austin notes here might profitably be connected with another of Wechsler’s subjects, another great perceiver, Oliver Sacks.

Edited: 66 minutes in, and I really don’t think Chelsea will score against 9 men. ⚽️

Mann's Joseph: 4

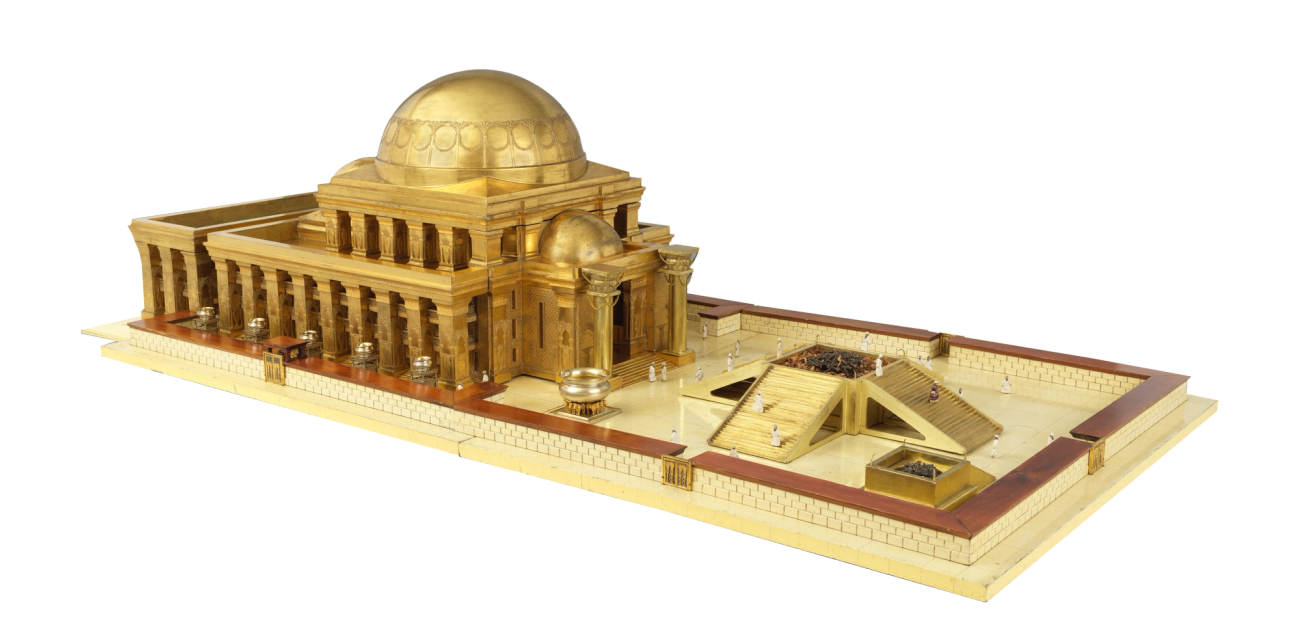

This is Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, who renamed himself Akhenaten. In every surviving representation of him he is immediately recognizable; no one else looks like him. There is good reason to believe that he instructed his artists to portray him in a certain manner, a manner especially evident in full-length portrayals:

He always bears the same features: a high-cheekboned face with slanting eyes and full lips; a narrow waist; a bit of a pot-belly; wide, feminine hips; full thighs and spindly calves. It’s hard to imagine why he asked to be portrayed in this way unless this is, to some degree anyway, what he actually looked like, but some scholars — for instance, Jacobs Van Dijk here — have noted that the artwork that survives from his reign portrays all people in a similar way, though no such mode of representation preceded this era. It is as though Akhenaten decreed himself the image of humanity. It can’t be accidental that he looks like a pregnant woman, like someone about to give birth to something.

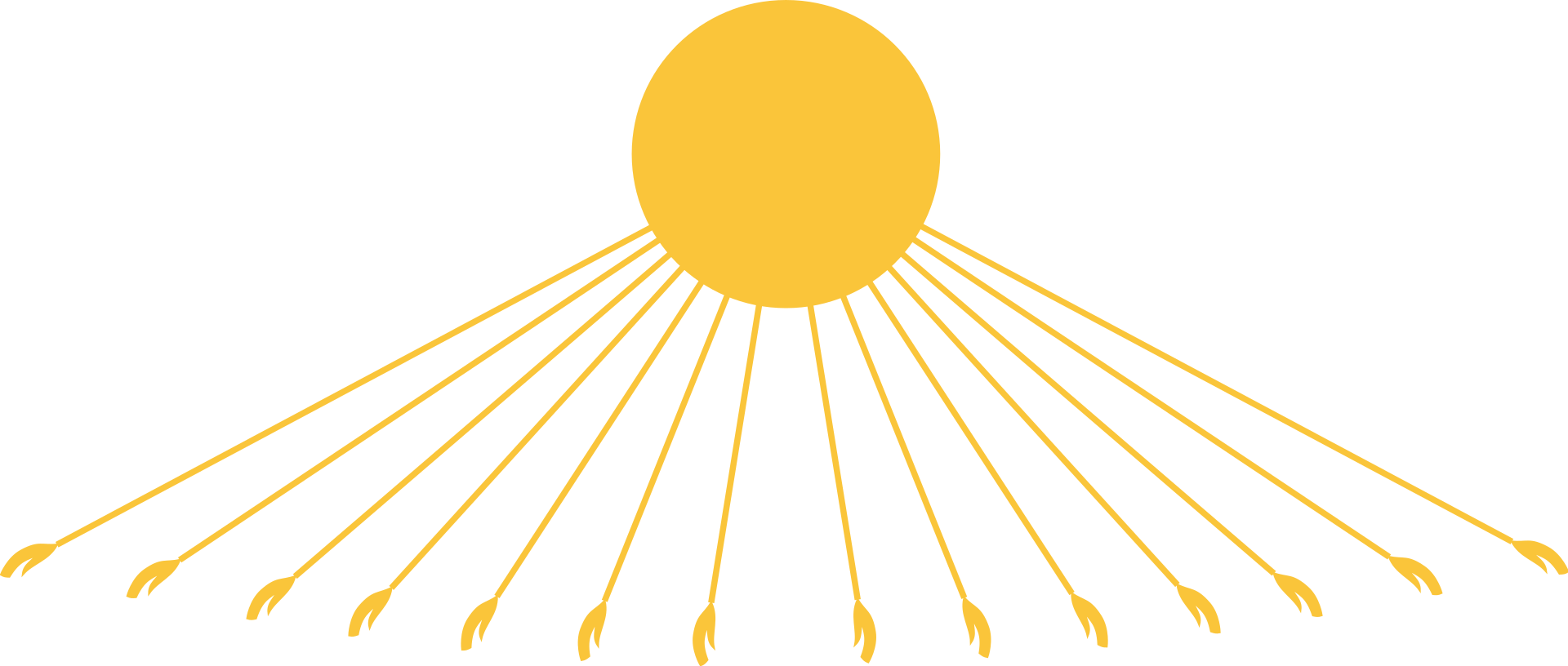

His wife, Nefertiti, gave birth to at least six daughters, but what he gave birth to was the most radical religious reformation ever undertaken: the elimination of the entire vast system of Egyptian worship and the replacement of every cult of every god with a single cult: that of the Aten, the disc (or globe) of the sun. The Egyptians already had a sun-god, of course, Ra, or Amun-Ra, who looked like this:

Sometimes (after he was in some sense united with the sun-god Ra) he has a falcon’s head. But Aten looked like this:

The refusal of human or animal imagery was very much the point, though I guess the Aten in a way has hands: like the Beatles, it has arms enough to hold you.

Akhenaten of course doesn’t mean to suggest that this is what the only God actually looks like: it is merely a visual representation of universality. The idea that a god “looks like” anything, even metaphorically, is part of what he wants to overcome. The great Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie wrote of this new theology,

If this were a new religion, invented to satisfy our modern scientific conceptions, we could not find a flaw in the correctness of this view of the energy of the solar system. How much Akhenaten understood, we cannot say, but he certainly bounded forward in his views and symbolism to a position which we cannot logically improve upon at the present day. Not a rag of superstition or of falsity can be found clinging to this new worship evolved out of the old Aton of Heliopolis, the sole Lord of the universe.

On the other hand, a later Egyptologist, Sir Alan Gardiner, in his classic Egypt of the Pharaohs, has a terser description of Akhenaten: he calls him a “heretic.”

The wonderful idea at the center of Joseph and His Brothers is this: Akhenaten is the Pharaoh who made Joseph his vizier. And thus the thematic tension between monotheism and polytheism is heightened — for, when these two men meet, who is more of a monotheist?

Mann is of course neither the first nor the last to speculate on the possible relationship between Akhenaten’s monotheism and that of Israel. I am not sure, but I believe that the American archaeologist James Henry Breasted was the first scholar to note the relationship between Akhenaten’s Great Hymn to the Aten and (for instance) Psalm 104. Speculation has usually focused on the possible influence of Egypt on the Israelites, in part because the Israelites were a dependent and then an enslaved people, but also in part because the tradition of seeing Egypt as the source of religious ideas for the rest of the world goes all the way back to Herodotus (see the Histories, Book II ¶ 50ff).

This is how Freud thought of the matter, in Moses and Monotheism, which presents us with Moses as an Egyptian adherent of Atenism. (It’s an incoherent book, alas — written as Freud was dying and little more than a confused riff on Breasted’s work.) This is also how C. S. Lewis thought of the matter. In his Reflections on the Psalms — written twenty years after Freud’s book, which Lewis may or may not have known — he wrote of Akhenaten’s revolution,

As we can see, it was a total failure. Akhenaten's religion died with him. Nothing, apparently, came of it.

Unless of course, as is just possible, Judaism itself partly came of it. It is conceivable that ideas derived from Akhenaten's system formed part of that Egyptian 'Wisdom' in which Moses was bred. There is nothing to disquiet us in such a possibility. Whatever was true in Akhenaten's creed came to him, in some mode or other, as all truth comes to all men, from God. There is no reason why traditions descending from Akhenaten should not have been among the instruments which God used in making Himself known to Moses. But we have no evidence that this is what actually happened. Nor do we know how fit Akhenatenism would really have been to serve as an instrument for this purpose.

Lewis’s thoughts on Akhenaten are interesting enough that I may have to return to them in another post. But for now I just want to note that his way of considering the relationship (which is also the archaeologists’ way) is not the only possibility. What if the flow of influence were reversed? What if one son of Israel, having risen to the position of Pharaoh’s vizier, had the eloquence and imagination to plant the monotheistic seed? — to plant it in fertile and ready ground, to be sure, but to plant it nonetheless. That is the possibility that Mann invites us to consider.

And perhaps he reminds us also of another point, not a possibility but a reality. Akhenaten’s revolution failed utterly: his son Tutankhaten removed the Aten from his name and became Tutankhamun, affirming his loyalty to one of the gods his father had attempted to banish, Amun-Ra. Of course, ultimately all the gods of Egypt failed; but the children of Israel thrived, and despite countless setbacks, persecutions, and pogroms, despite living for centuries among people who have wanted and still want to destroy them altogether, still to this day worship the God of their fathers, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

As a long-time Arsenal supporter, I am not happy with the club leadership’s behavior. ⚽️

time to shut up

)

As an Arsenal supporter who believes that Arsenal did indeed get robbed on that Newcastle goal, I am not a fan of this statement. For several reasons:

- That was just one goal, and focusing on the refereeing mistakes that led to it shifts attention from the Gunners’ manifest ineptness in attack. Arteta should be more concerned about his and his players’ shortcomings than about those of the refs.

- This statement won’t do what the club wants it to do, and indeed will probably be counterproductive. Do Arsenal really believe that the refs, and the Premier League and the F.A. more generally, can be shamed and bullied into doing better? My guess is that the side will get worse treatment for the rest of the season thanks to Arteta's whining and bitching and the club’s endorsement of it.

- This sets a really bad example for the players, who will be learning from their club’s leadership how to act when things go wrong for them: Don’t own your shortcomings, but blame blame blame, and do it in your loudest voice.

- A much better approach would be to seek collective action: talk to other clubs who are, or ought to be, angry about the shocking incompetence of the VAR system, and try to lead collective action — and lead it behind the scenes. That might not be as emotionally gratifying, but it would be infinitely more effective.

This whole situation is very sad, because Arsenal have the most attractive young side in the league. They could easily be making fans, but instead they seem to be determined to make enemies. And if you were a transfer target, is this a club you’d want to play for? Last year the answer would have been a big Yes; now I suspect it’s leaning more and more towards No. Instead of a place of joy and excitement, it’s starting to feel like the Bruno Fernandes of clubs: talented but incessantly and frustratingly bitchy.

An exceptionally promising era in the club’s history just may be giving way to something much darker, and that is wholly the fault of the team leadership’s emotional immaturity and incontinence. It’s time for Arteta & Co. to shut their mouths and get better.

NYT: “The possibility of collision isn’t the only problem with cramming low Earth orbit past capacity. Starlink satellites are already hampering astronomy research done from ground-based telescopes (and even Hubble) with visual occlusions and radio noise; the ambient light scattering off all those extra bodies also risks corrupting the darkness of night. The scientific and cultural resource of the night sky is in danger of being extinguished.”

Mann's Joseph: 3

This difference we have identified between Jacob and Joseph is essential to the story that will unfold, for whether Joseph is a better or worse theologian than his father, his habits of mind are essential to the calling he will assume, the vocation of saving his family.

Again in this opening chapter, Joseph reflects on his name and the important fact that it contains the word sepher (or sefer), which means book or scroll or document. “He loved composing with the stylus and was so skilled at it that he could have served as a junior scribe at some place where documents were collected” (68).

Later, after his brothers sell him into slavery and he finds himself in Egypt, working in the household of a rich and powerful man named Petephrê (Potiphar), he actually becomes a scribe, and Petephrê’s overseer, Mont-kaw, contemplates this boy:

And here Joseph stood before him, scroll in hand, and, for a slave, even a scribal slave, he spoke clever, rougishly subtle words — and that combination of ideas was unsettling. This young Bedouin and Asiatic did not have the head of an ibis on his shoulders, and was, needless to say, a human being, not a god, not Thoth of Khmunu. But he had intellectual connections with that god, and there was something ambiguous about him…. [651]

Again and again in the tetralogy Joseph is associated with the Egyptian god Thoth. Thoth was the god of writing, of communication; he was also a wise counselor and mediator, and a messenger. In a story Socrates tells in Plato’s Phaedrus, Thoth offers the gift of writing to one King Thamus, who rejects it. When the Greeks learned about Thoth they immediately recognized him as a version of Hermes, or rather — since they were often inclined to see themselves as inheritors of Egyptian wisdom — recognized Hermes as a version of Thoth.

At several key points in the story Joseph encounters a nameless figure who is a guide — especially a guide to the Underworld that is Egypt — and a messenger. This is clearly Thoth/Hermes. Maybe I’ll write about him in a later post. But right now I am concerned with Joseph’s own Thothness: what he ultimately becomes is the go-between, the messenger, the mediator, who links his family — his radically monotheistic nomadic-shepherd family — with the great Egyptian empire, full of magnificent cities and temples and a near-infinity of gods. Only Joseph can mediate those two worlds.

For much of the book, I assumed that in telling Joseph’s story Mann was essentially writing a critique of monotheism, at least in its Israelite form; that he was teaching us that Joseph’s flexible and quasi-syncretic way is the better way. But eventually I was forced to reconsider that view.

sigh

Paul Davids is a guitarist who, a while back, did a neat YouTube tutorial on Paul Simon’s “Fifty Ways to Leave Your Lover.” But recently he received an email telling him that he had gotten a couple of the chords slightly wrong. The author of that email? Paul Simon.