BRB, I gotta take all these unused minutes to the

My old friend Noah Millman with a moving meditation on his own first name – and on “the crooked timber of humanity.”

one cheer for "negative experience"

Once you have the reader’s empathy, though, you must keep it. You must persuade the reader to trust you enough to lower their guard, to let go of the constant low-level self-protection most of us experience in the real world. This means you must be very, very careful how you handle negative experience. Every reader is different, and you can’t please everyone, but my personal bias (and I’m far from alone in this), is extreme antipathy to wanton cruelty towards helpless living things. If you make me empathize with a dog or child or young woman, and then torment them using visceral language, I will experience visceral revulsion, throw the book at the wall, and never read anything you write again. I won’t trust you.

I feel exactly the same way about the same things, and yet I am reluctant to endorse the prescription Griffith makes. For one thing, the category of “negative experience” is so vast and amorphous that, especially when you consider the obvious fact that, as Griffith says, “every reader is different,” it’s hard to think of anything that would clearly escape it. Reading about a happy family might be a “negative experience” for someone whose family is unhappy.

No, I’m inclined to say to writers, Don’t be careful about portraying negative experience or any other kind of experience. If Shakespeare and Dostoevsky and Toni Morrison had been careful, we wouldn’t have King Lear, The Brothers Karamazov, and Beloved — three works that have been enormously painful to many readers. But that pain hasn’t always been bad; sometimes, for some readers, I am inclined to say for most readers, it has been necessary.

I just don’t think we need more books written by people who walk on eggshells for fear of offending or hurting. A world in which some readers are wounded by what they read is not an ideal one, but a world in which writers self-censor to avoid disturbing those most prone to disturbance would be worse. There are other and better ways to protect endangered people than muzzling our writers.

UPDATE: One more point. Griffith’s essay, like much writing on arts and ideas these days, operates from the assumption that any given reader’s vulnerabilities and sensitivities are fixed, unchangeable. The idea that a sensitive reader could become less sensitive, or could adapt to his or her sensitivities in some constructive way, is not on the table. I think it ought to be on the table.

the nature of the transaction

Ross Douthat addressing prospective donors to universities, the kind who keep giving to Harvard and Yale:

If you want actual influence over American academic life, you’re just much better off finding a smaller or poorer school where your money will be welcomed, your opportunities to effect real transformation will be ample and your millions can build something dynamic or beautiful without always fighting through the thicket of powerful interest groups that grows up around powerful institutions. And to harp again on a frequent theme, if you’re absurdly, obscenely rich and care about higher education, you should Google “Leland Stanford” and then go and do likewise.

Ross goes on to talk about donors who are motivated by the warm, fuzzy memories of their undergraduate days at such institutions — and tells them that they need to get over that — but I wonder: How many big donors are in fact thinking of their Happy College Days? Maybe they were happy, maybe they weren’t; maybe they appreciated the education they received, but more likely they don’t think about that at all. And how many genuinely desire to influence American academic life? Almost none, I suspect. I tend to think that the situation is more purely transactional:

- Assuming that these donors did attend an elite university, attending an elite university was for them a ticket to social capital and financial capital;

- Having acquired more financial capital than they could ever spend in a dozen lifetimes, they nevertheless find themselves longing for ever more social capital, more cultural approval, more cachet;

- And so they contribute to the universities that can give them that, which is to say, the most elite universities — no lesser school can provide what they’re willing to pay for. (How many of them have even had one instant’s thought about the future students they could help along the way? You don’t get that rich by thinking about other people.)

Maybe in some general and theoretical sense they’d like to have influence over those universities, and maybe they complain when they discover that they don’t have it, but that’s like discovering that there’s no valet parking at the elegant restaurant where you’ve booked a table: annoying, but hey, you’re not there for the parking.

FWIW, one of my favorite things I’ve published in recent years is this reflection on the big Blake exhibition at the Tate Gallery.

would it kill you to allow the occasional German word

I’ve made a case for reading the news less often.

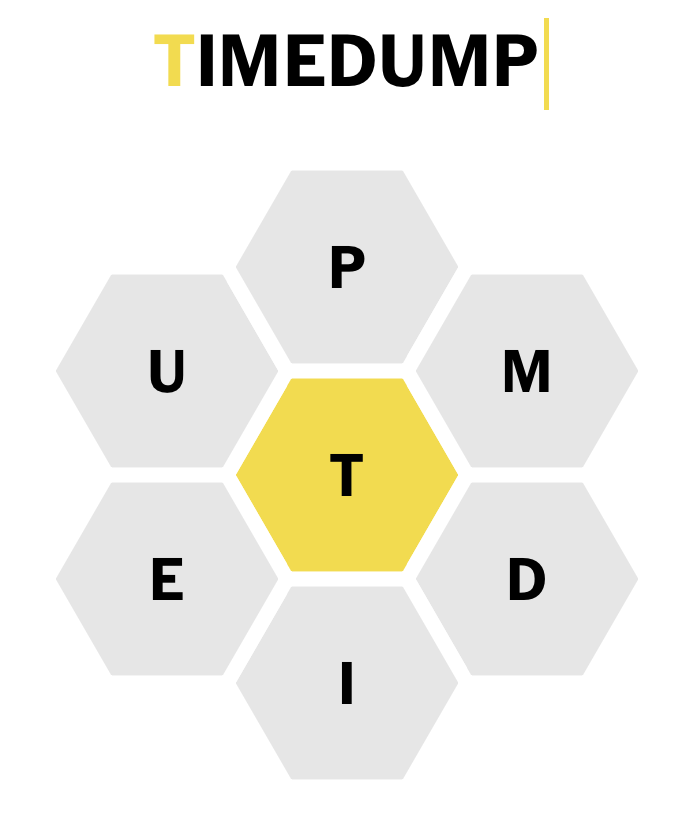

periodicity

This piece from the Dispatch (possibly paywalled) on how The New York Times misled its readers with an overly “Hamas-friendly” headline makes a valid point, I guess — but I think much of the problem here is baked-in to minute-by-minute journalism. You don’t have to be a hard-core opponent of Israel to get a headline like that wrong — in the heat of the moment even a slight lean towards the people living in Gaza might be enough to influence your headline. If you have to post something on your website, and post it right now, you’ll not be consistently judicious and fair-minded.

[UPDATE: The Times has published an apology.]

I didn’t know that the Times had perpetrated this headline because any political crisis strengthens me in the habits I have been trying to cultivate for some years now: to watch no TV news at all — that part’s easy, I haven’t seen TV news in the past thirty years, except when I’m in an airport — and to read news on a once-a-week rather than a several-times-a-day basis. My primary way to get political news, national and international, is to read the Economist when it shows up at my house, which it does on Saturday or Monday. (I don’t keep the Economist app on my phone.) I have eliminated political sites from my RSS feed, and only happened upon the Dispatch report when I was looking for something else at the site.

The more unstable a situation is, the more rapidly it changes, the less valuable minute-by-minute reporting is. I don’t know what happened to the hospital in Gaza, but if I wait until the next issue of the Economist shows up I will be better informed about it than people who have been rage-refreshing their browser windows for the past several days, and I will have suffered considerably less emotional stress.

It’s important to remember this: businesses that rely on constant online or televisual engagement — social media platforms, TV news channels, news websites — make bank from our rage. They have every incentive, whether they are aware of it or not, to inflame our passions. (This is why pundits who are always wrong can keep their jobs: they don’t have to be right, they just have to be skilled at stimulating the collective amygdala.) As the intervals of production increase — from hourly to daily to weekly to monthly to annually — the incentives shift away from being merely provocative and towards being more informative. Rage-baiting never disappears altogether, but books aren’t well-suited to it: even the angriest book has to have passages of relative calm, which allows the reader to stop and think — a terrible consequence for the dedicated rage-baiter.

“We have a responsibility to be informed!” people shout. Well, maybe, though I have in the past made the case for idiocy. But let me waive the point, and say: If you’re reading the news several times a day, you’re not being informed, you’re being stimulated. Try giving yourself a break from it. Look at this stuff at wider intervals, and in between sessions, give yourself time to think and assess.

UPDATE 2023–10–23: One tiny result of the Israel/Gaza nightmare, for me, is that it has revealed to me those among the writers I follow via RSS who are prone to making uninformed, dimwitted political pronouncements. Those feeds I have deleted without hesitation.

I’m really worried about Bandcamp, which is a unique and probably irreplaceable service. At this point, there’s one thing we all ought to have learned: when the founders of a service or app we love sell it, that means it’s time for us to get out. It will not last in the form we love. Key quote from the piece:

Cultural theorist Cory Doctorow coined the term ‘enshittification’ to describe the agonizing process by which online platforms shift their focus from end users to maximizing value for their shareholders. It’s a crudely effective concept capable of capturing everything from the declining quality of Google’s search results to the way your Instagram feed is full of Reels you never asked to see. (Let’s not even get started on the rot at the heart of whatever Twitter is now.) When Bandcamp’s founders sold the company to Epic, that should have been the first sign that the platform belonged to someone other than its users. Songtradr’s layoffs and promises of synergy with its music licensing business are the next indicator that the ugly specter of enshittification may be nigh. The saddest thing is, aside from a benevolent billionaire sweeping in and buying up the site, or building out an alternative, there are no easy answers here. It’s another reminder that the independent music ecosystem is far more fragile than anyone would like to admit.

A fascinating account of the endlessly variable and thus confusing history of the word “Palestine.”

Anthony Lane on the science of happiness:

Whether there is still a place for the steady intellectual grind is open to question. Readers and publishers alike are worried by all that worrying. Understandably, their quest is for books that promise results, primed to beef up one’s eudaemonia levels like a shot of Vitamin B12. Hence the speed with which the mood of Brooks’s book, grammatical and tonal, is set within the title: not “How to Build” but “Build.” Thereafter, the imperative reigns supreme. “Start by working on your toughness.” No sweat. “Take your grand vision of improvement and humble ambition to be part of it in a specific way and execute accordingly.” Check. “Rebel against your shame.” Done. “Widen your conflict-resolution repertoire.” Ka-pow! “Treat your walks, prayer time, and gym sessions as if they were meetings with the president.” Which President? “Journal your experiences and feelings over the course of the day.” Since when did “journal” turn into a transitive verb? “Dig into the extensive and growing technology and literature on mindfulness.” Sorry, I was miles away, what? Above all, “Remember: You are your own CEO.” Holy moly. Do I have to wear a suit to brush my teeth? Is my dog a shareholder? Were last year’s migraines tax-deductible? Can I be fired by me?

But even at night ...

Clockmakers, flush with commissions, let their horological imaginations run wild. They mounted every last thing they could think of on their clocks: trumpeting angels, wheels of fortune, planets and stars wheeling around in epicycles – take that, astrolabe – and panoplies of bells to add to the din of holy clanging. The still-extant clock of Wells Cathedral, constructed about 1390, is a carnival of time. A face of three concentric circles shows the 24 hours, the position of the sun and the phases of the moon, all decorated with stars, angels and depictions of the four cardinal winds. Every fifteen minutes, four knights come out to joust. Above the clock an automaton (‘Jack Blandifer’) kicks his heels on bells every quarter hour. In the 15th century an exterior clock was geared onto it: two axe-men stand and strike two more bells on the hour. Nequid pereat, runs the inscription – let nothing perish, no matter how whimsical.

Here is the marvelous clock of Wells Cathedral:

(Larger version, well worth inspecting, here.) And here, at least as admirable, is Simon Armitage’s glorious poem “Poetry”:

In Wells Cathedral there’s this ancient clock,

three parts time machine, one part zodiac.

Every fifteen minutes, knights on horseback

circle and joust, and for six hundred yearsthe same poor sucker riding counterways

has copped it full in the face with a lance.

To one side, some weird looking guy in a frock

back-heels a bell. Thus the quarter is struck.It’s empty in here, mostly. There’s no God

to speak of — some bishops have said as much —

and five quid buys a person a new watch.

But even at night with the great doors lockedchimes sing out, and the sap who was knocked dead

comes cornering home wearing a new head.

Ida York Abelman, “Man and Machine”

I wrong a longish and complicatedish post on conceptual screens and diseases of the intellect.