I wrote about biblical illiteracy among scholars, and why I think the role model for such scholars ought to be Bertie Wooster.

I wrote about the murder of Seamus Heaney’s cousin and the two poems he wrote about it.

the danger of eulogy

In 1975 Seamus Heaney’s second cousin Colum McCartney — whom it seems he did not know personally — was murdered by members of the Glenanne Gang, Ulster Protestants engaged in a campaign of terror that largely involved killing Catholics at random. McCartney and a friend were returning to their homes in Ulster from a football match in Dublin when they were stopped at a police checkpoint — which turned out to be not a police checkpoint at all. Both were shot in the head.

Soon thereafter, Heaney wrote a poem, “The Strand at Lough Beg,” in memory of McCartney. (It is in his collection Field Work.) In the poem’s final stanza the dead man appears to the poet, appears not where he was killed — that happened “Where you weren’t known and far from what you knew” — but at Lough Beg, a place familiar to the family:

Across that strand of ours the cattle graze

Up to their bellies in an early mist

And now they turn their unbewildered gaze

To where we work our way through squeaking sedge

Drowning in dew. Like a dull blade with its edge

Honed bright, Lough Beg half shines under the haze.

I turn because the sweeping of your feet

Has stopped behind me, to find you on your knees

With blood and roadside muck in your hair and eyes,

Then kneel in front of you in brimming grass

And gather up cold handfuls of the dew

To wash you, cousin. I dab you clean with moss

Fine as the drizzle out of a low cloud.

I lift you under the arms and lay you flat.

With rushes that shoot green again, I plait

Green scapulars to wear over your shroud.

A scapular, worn primarily by monks and priests, offers here an image of prayer and hope, and the poem is prefaced by a quotation from Dante’s Purgatorio. In caring for the body of his dead cousin, then, Heaney is preparing him for his final journey.

Some years later, in Heaney's harrowing sequence “Station Island” — a sequence shaped more thoroughly by long meditation on Dante than the earlier poem had been — the poet is again visited by his dead cousin, and the visit is not pleasant. In the first poem the poet speaks while the murdered man is silent; in the second the poet must listen to the voice of man he had eulogized. The sequence narrates a pilgrimage to St. Patrick’s Purgatory, a journey involving several encounters with the dead, very like those Dante experiences in his voyage through the Three Realms — except often more uncomfortable.

We have reached the eighth station. Heaney is conversing with “my archaeologist” — Tom Delany, his friend, who died of tuberculosis at age 32 — when suddenly his cousin Colum appears, with a word of accusation:

But he [Delany] had gone when I looked to meet his eyes

and hunkering instead, there in his place

was a bleeding, pale-faced boy, plastered in mud.

‘The red-hot pokers blazed a lovely red

In Jerpoint point the Sunday I was murdered,’

he said quietly. ‘Now do you remember?

You were there with poets when you got the word

and stayed there with them, while your own flesh and blood

was carted to Bellaghy from the Fews.

They showed more agitation at the news

than you did.’

(The Fews is the part of County Armagh where McCartney was murdered; Ballaghy is the village in County Londonderry where Heaney was born and raised and where McCartney was buried.) You did not clean my body and lay me out for burial. You remained in the company of your fellow poets. Heaney pleads for himself, says that the news made him “dumb,” describes the image of Lough Beg just outside Bellaghy that rose unbidden to his mind. (His mind went to the home town they shared, but his body did not.)

Colum is not appeased.

You saw that, and you wrote that — not the fact.

You confused evasion and artistic tact.

The Protestant who shot me through the head

I accuse directly, but indirectly, you

who now atone perhaps upon this bed

For the way you whitewashed ugliness and drew

the lovely blinds of the Purgatorio

and saccharined my death with morning dew.

You confused evasion and artistic tact. You told yourself you heeded your calling by shaping the story artfully, festooning it with imagery; in fact you merely whitewashed the ugliness of my murder. To this charge the poet makes no response — except, of course, the poem itself, which is in fact made of Heaney’s own words, not Colum McCartney’s.

And this is both the problem and the wonder. Philip Larkin once said, in response to a comment about how “negative” his poems are, that “The impulse for producing a poem is never negative; the most negative poem in the world is a very positive thing to have done.” Colum’s accusation against his cousin is just this, that he has done a positive thing — but then, the accusation itself, being couched in masterful verse, is also a positive thing. The poet’s eulogy must be beautiful, even (especially?) when the dead one’s murder was hideous beyond our ability to confront it. It is only in the language of poetry that the poet can acknowledge the limits of the language of poetry.

As I keep saying: Arteta and Southgate between them are trying ensure that Saka’s career will be over by age 25. Grrrrrrr. ⚽️

Max Rushden: “Do VARs have to be referees? They are different skills. How much would those in charge of it, the referees’ body PGMOL, benefit from hiring from a wider pool of people?” This is exactly correct. We have learned that even the best refs can be utterly incompetent at VAR, and apparently most of them hate doing it. Choose people with lower levels of physical fitness but better brains. ⚽️

Who is more at fault, the person who always chooses Reply All or the person who, by CCing rather than BCCing, made the Reply All possible?

NYT: “Most major U.S. cities now have at least three times as many security guards on the street as sworn police officers, even though guards typically operate with minimal oversight, less training and little power to enforce the law.” I had no idea!

Richard Gibson: “‘Why I Write’ is often handed to students as an encouragement to ponder their own motivations, becoming, in effect, the writerly version of a personality test. Are you strongly worried about true facts but also socially engaged? Then you’re showing signs of HI-PP. Or are you maybe AE-SE, hungry for approval but stimulated by beauty? Could you be PP-SE, politically conscious but a total egoist? Occasionally, critics cite Orwell’s list when evaluating famous authors. Dickens? Definitely, PP-SE. George Eliot? HI-PP. Joyce? How about AE-HI?”

The problem with this meme is its assumption that, for the people in question, there’s anything beyond Phase 1. But what if Phase 1 is the entire program?

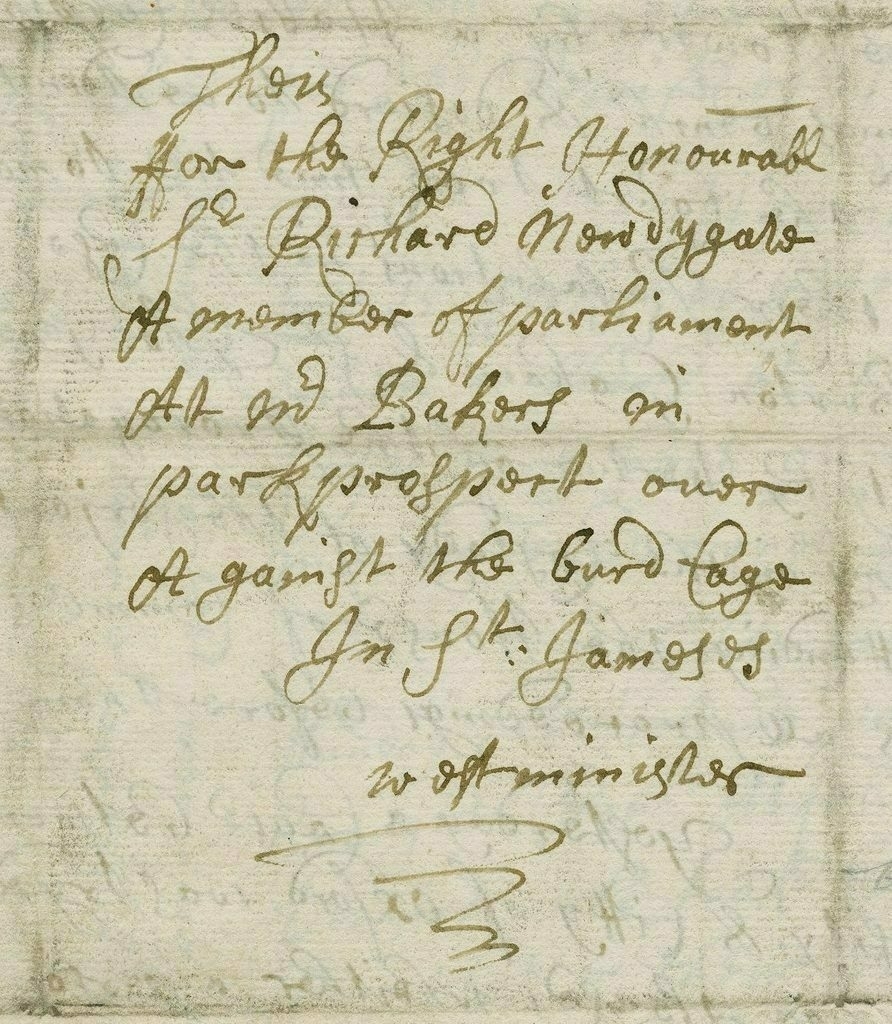

Addressing a letter in the days before standardized addresses could be difficult.

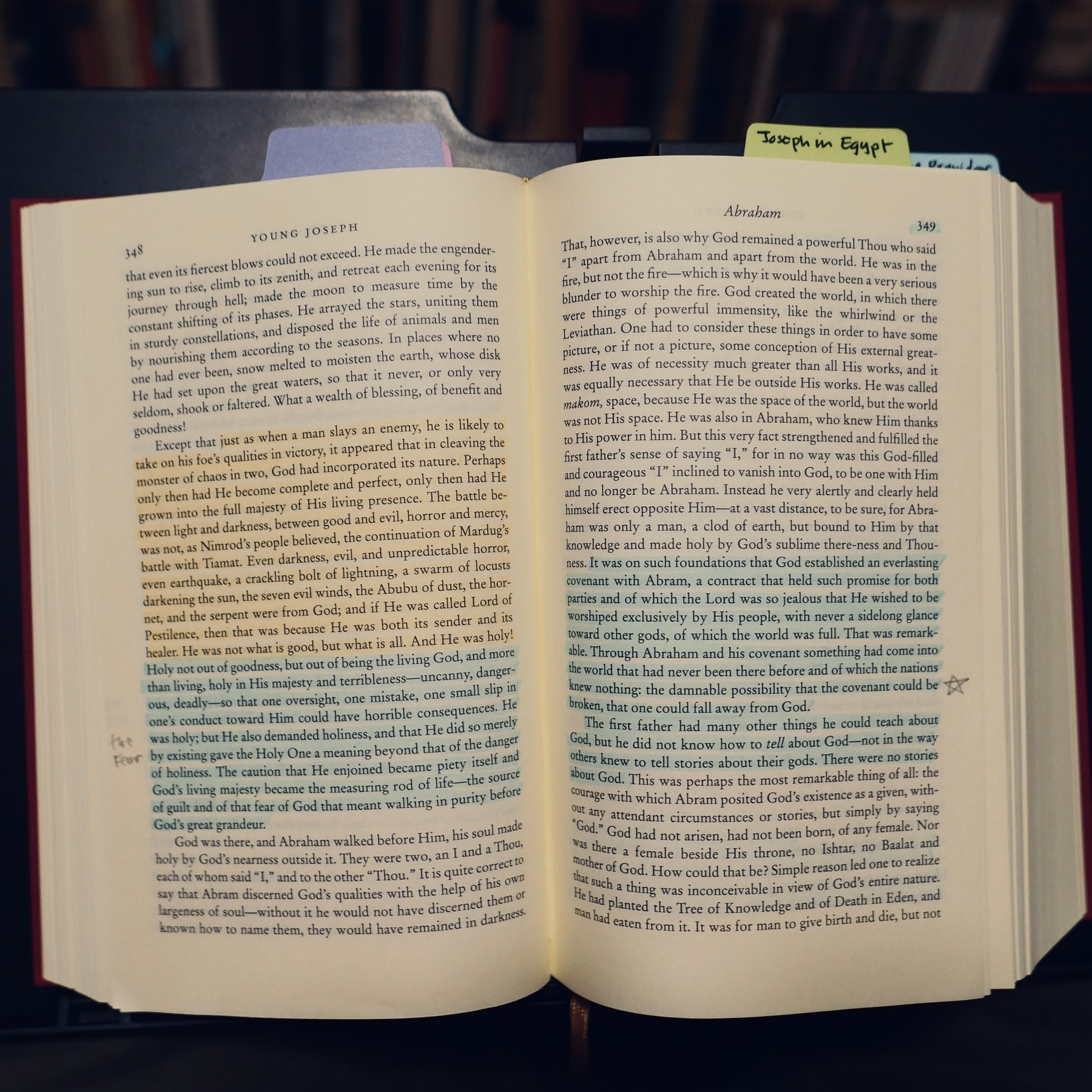

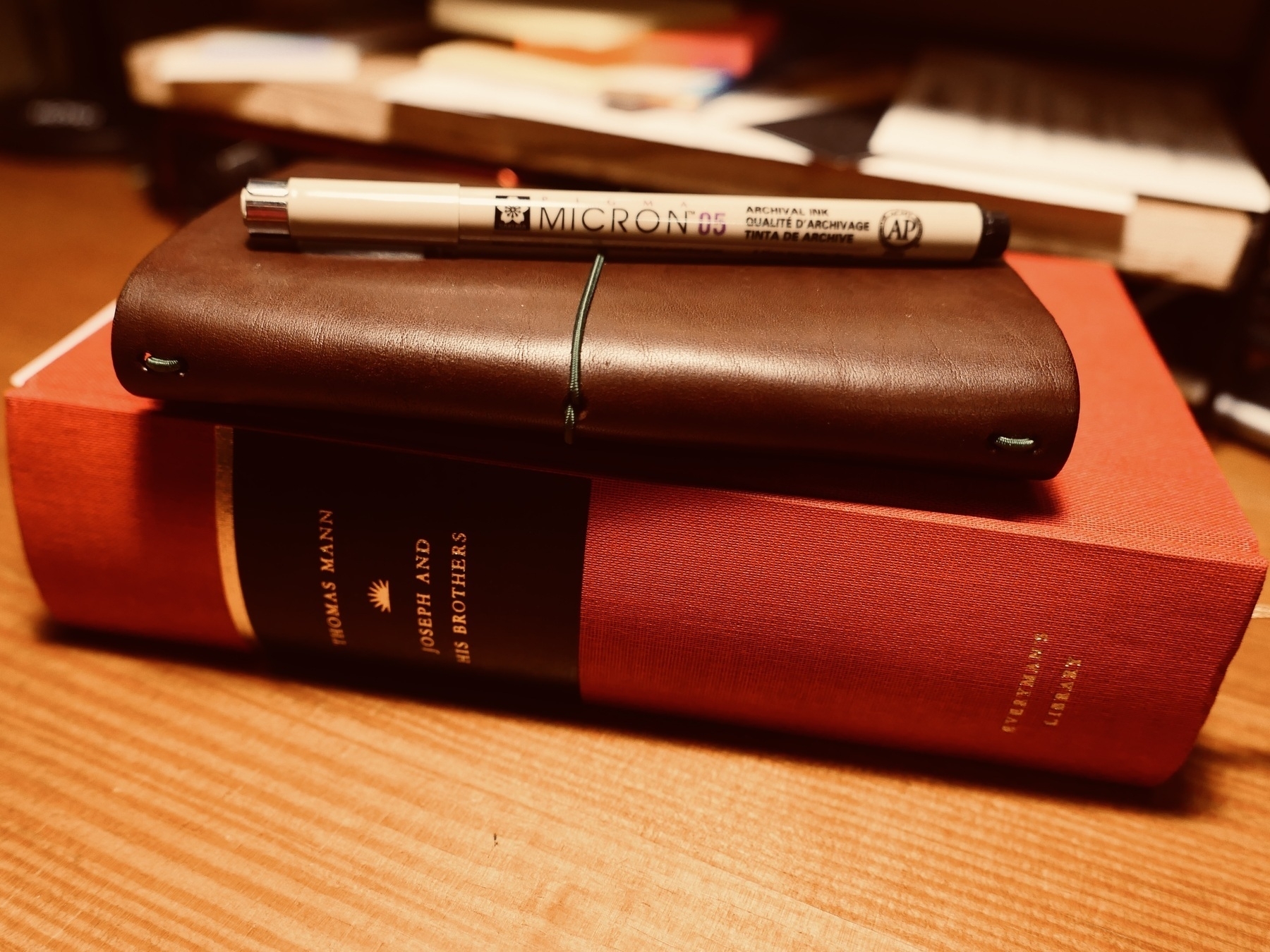

A complex book needs a complex annotation method: multiple highlighting colors, underlining, detailed notes on the endpapers (not shown). My ideal job would be Book Annotation Artist. I would carefully read and appropriately mark up difficult books, then sell those books at auction. It would be hard to part with them, but then, that’s how painters and sculptors feel.

Damon Krukowski: “Independent musicians can’t even talk about coordinated collective action against our corporate overlords - like organizing a consumer boycott, or withholding our work in some strategic manner. If we did, we could be sued under – get this – antitrust laws.” Who knew?

I wrote about Jane Austen and parents.

Austen and parents

One of the most notable traits of Jane Austen’s fiction is its gently ironical attitude towards many of its own readers. Consider Emma, for instance. Here is Austen’s description of the key event in Emma Woodhouse’s life: “It darted through her, with the speed of an arrow, that Mr. Knightley must marry no one but herself!” Every reader of the novel (myself included) will tell you that this is a glorious moment. But note: the novel consists of 55 chapters, and this decisive moment occurs in the 47th of them; in the 49th Mr. Knightley proposes to her and is accepted; and so everything that the reader most cares about is wonderfully sorted out. But six whole chapters remain. And why is that? Because Jane Austen is interested in certain matters that her audience is not especially interested in – but (she thinks) ought to be.

Or consider Mansfield Park, in which Austen signals her deviance from popular expectation in a different way. Fanny Price has carried her torch for her cousin Edmund helplessly and hopelessly for several hundred pages – this is the longest of Austen’s novels – and then, a mere seven paragraphs from the end, we get this:

I purposely abstain from dates on this occasion, that every one may be at liberty to fix their own, aware that the cure of unconquerable passions, and the transfer of unchanging attachments, must vary much as to time in different people. I only entreat everybody to believe that exactly at the time when it was quite natural that it should be so, and not a week earlier, Edmund did cease to care about Miss Crawford, and became as anxious to marry Fanny as Fanny herself could desire.

As much as to say: “Oh, you still want Edmund and Fanny to marry, do you? Well, if you insist, be it so – but I really can’t be bothered to narrate their courtship.”

What Austen cares about – what she devotes her extraordinary intellectual energies to – is the moral and intellectual formation of young women. Austen perceives her society to be one in which people have great expectations for young women, and place exceptionally great demands upon them, but does almost nothing to prepare them to meet either the expectations or the demands.

In Mansfield Park Sir Thomas Bertram, the head of the family with whom the story is concerned, is a good man, an admirable man in many respects, but is regularly described as “cold” and “severe”; his wife, Lady Bertram, is called “indolent”; and Lady Bertram’s sister, the Mrs. Norris, who has the greatest influence over their daughters precisely because the parents are either cold or indolent, is “indulgent.” In Emma, Emma’s mother is dead and her father a hypochondriac whole manifold sensitivities make him, in his own way, as indolent as Lady Bertram.

Pride and Prejudice is more conventionally structured around the marriage of its heroine – which is perhaps why Austen thought that “The work is rather too light, bright and sparkling: it wants shade” – but even there one might argue that Elizabeth Bennett suffers in several ways from the moral idiocy of her mother and the ironic detachment of her father. But these, I submit, are not the typical dispositional errors of parents: the typical ones are laid out in Mansfield Park: severity, indolence, and indulgence.

Fanny Price and Emma Woodhouse from their childhood have older men in their lives who provide them guidance, counsel, and (in the end, as we have seen) matrimony. But along the way to that conventional Happy Ending they suffer many vicissitudes, painful episodes that, Austen suggests, they might not have suffered if their parents had provided them with consistent and loving guidance. When parents are badly formed, Auden consistently indicates, their children will be badly formed as well; and while poor moral formation is unfortunate for any children, in that particular society the girls consistently paid a bigger price. And not many girls are fortunate enough to have the regular attention of a Mr. Knightley or cousin Edmund.

Many pages read, many notes made, and … a thousand pages still to go. 😵💫

“There is a militant type of mind to which the hostilities involved in any human situation seem to be its most interesting or valuable aspect; some individuals live by hatred as a kind of creed.” – Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1962)

a path forward

- It’s certainly true that power corrupts, but it’s more true that the corrupt are drawn to power, so ultimately it doesn’t matter whether power is concentrated in government or in the market. (Assuming that “government” and “market” can be distinguished, which I doubt.) Wherever power is, the corrupt will be drawn to it by an irresistible magnetic force. So the only answer is to reduce the scope of power everywhere. That’s why I’m drawn to anarchism.

- Anarchism is the only possible means by which metaphysical capitalism might be resisted. By promoting emergent order it promotes cooperation and negotiation, which are forms of actual relationship that involve us in The Great Economy. Libertarianism, by contrast, leaves us related to one another only in the market economy, which means not truly related at all — just oppositionally positioned in a zero-sum game.

I just came across a writer who says his role is to be a truth-teller. I’d feel better about that if I saw any indication that he had ever been a truth-learner.